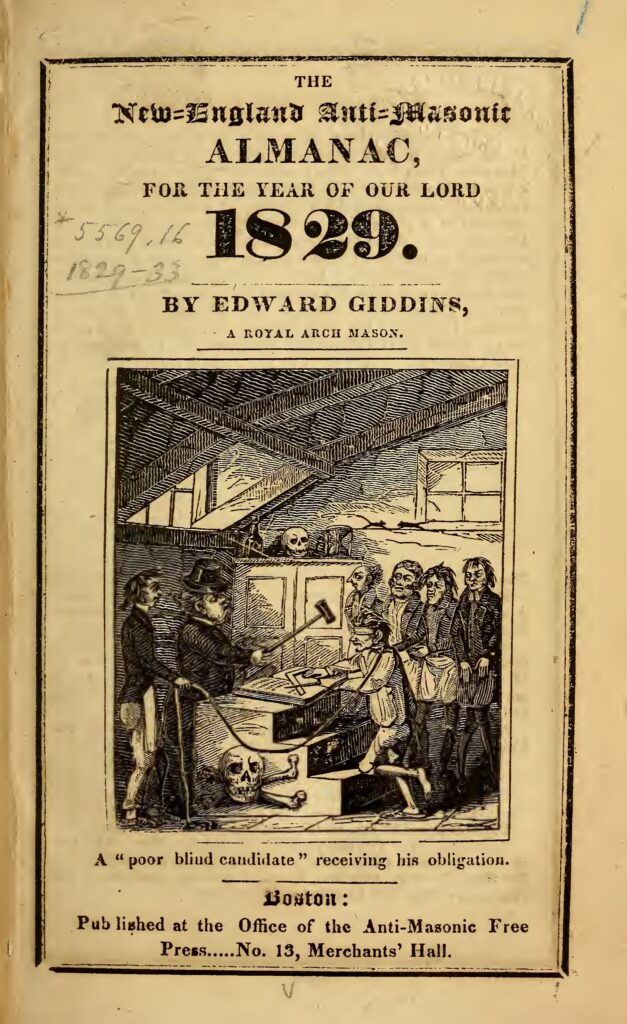

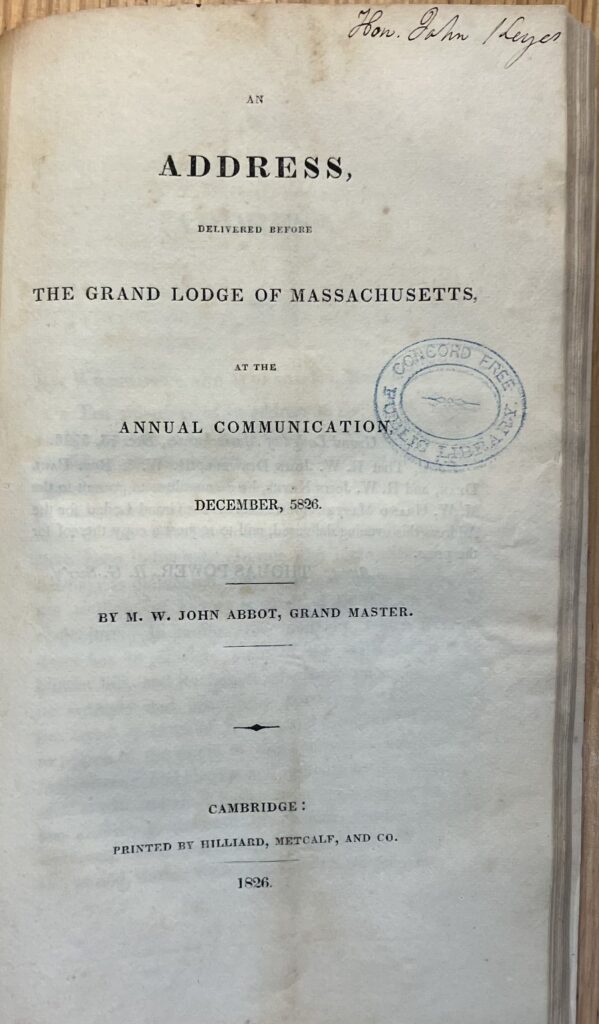

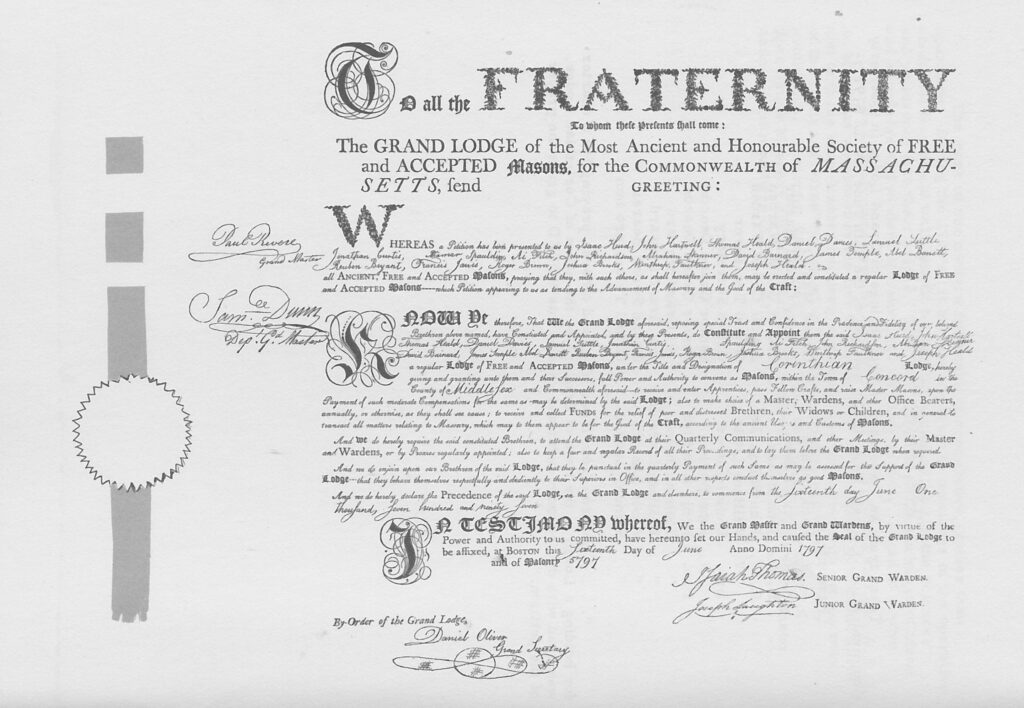

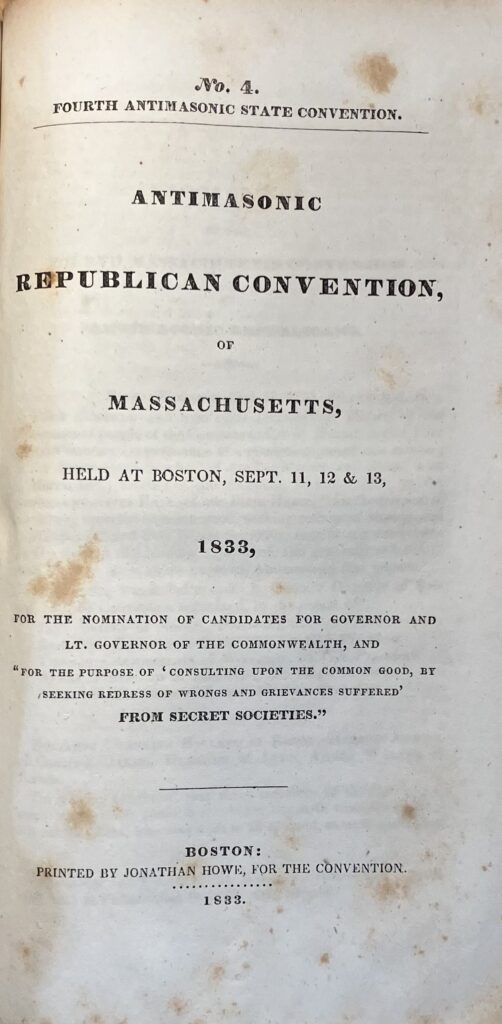

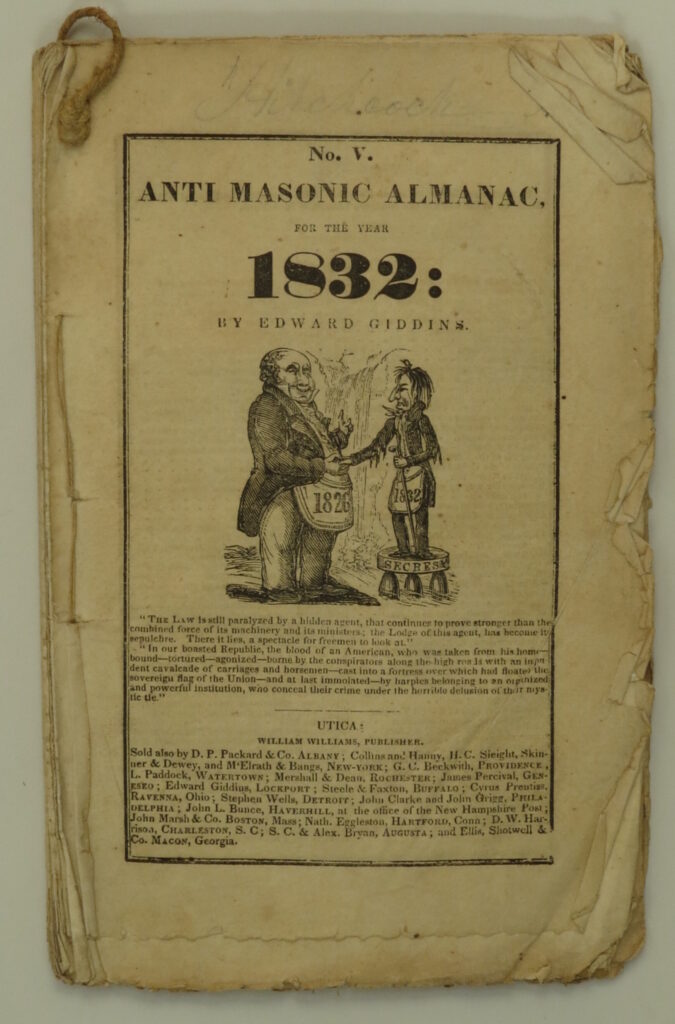

Nestled in a manuscript box and secured in a basement vault, three obscure volumes of bound pamphlets in the Special Collections of the Concord Free Public Library bear witness to the political upheaval of the decade from 1826 to 1835 known as Anti-Masonry. Its origins lay in New York State, where a renegade Freemason named William Morgan was abducted and murdered to prevent him from divulging the secrets of the fraternal order, and where local law enforcement officials clearly engaged in a cover-up of the crime to protect their guilty brethren. The ensuing protests mushroomed into a populist revolt against elite authority throughout the new republic and marked a turning point in the democratization of American life. Anti-Masonry came late to Concord, not until the winter of 1833, six years after the scandal erupted in upstate New York, and it burned itself out in three short but intense years. In its brief existence Anti-Masonry remade politics in the small town of two thousand inhabitants, ousted key figures in the local establishment, and transformed the conduct of public debate. It also forced the local Masonic lodge to hunker down and avoid public notice for a decade. The crusade set neighbor against neighbor in a bitter war of words that left its traces in the little collection of pamphlets at the Concord library. Herein are the polemics that polarized a New England town, soon to become famous as a center of Transcendentalism and the home of Emerson and Thoreau, and turned it upside down.

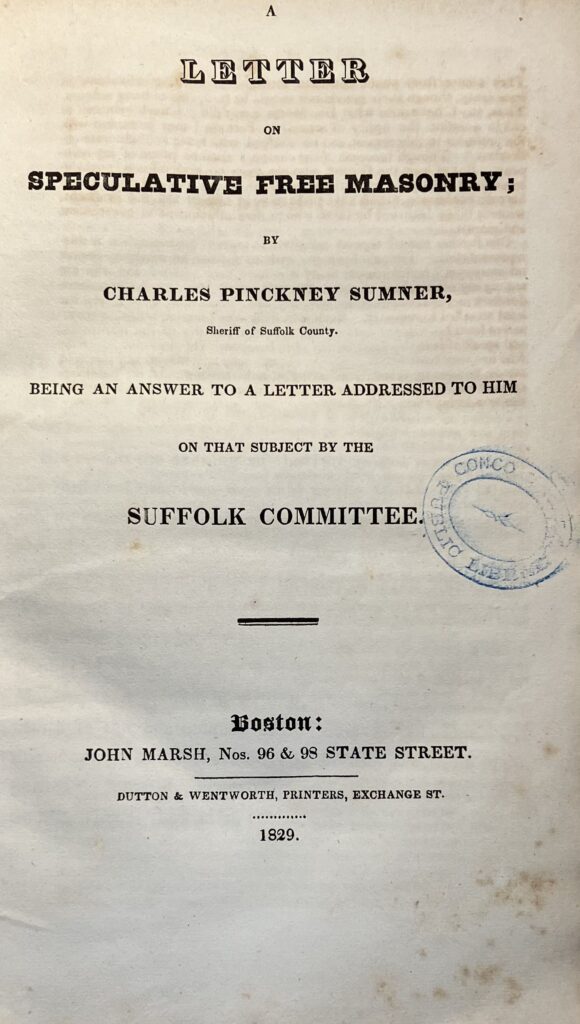

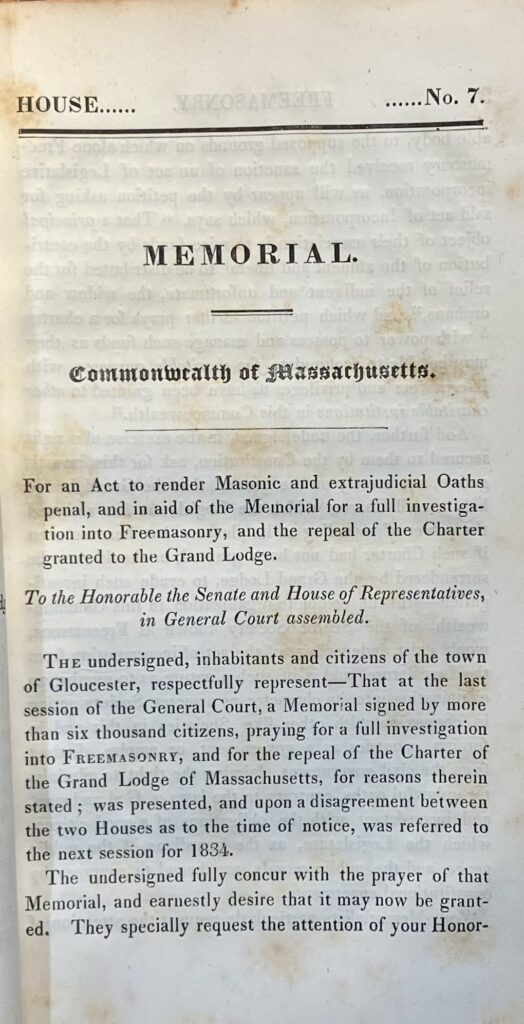

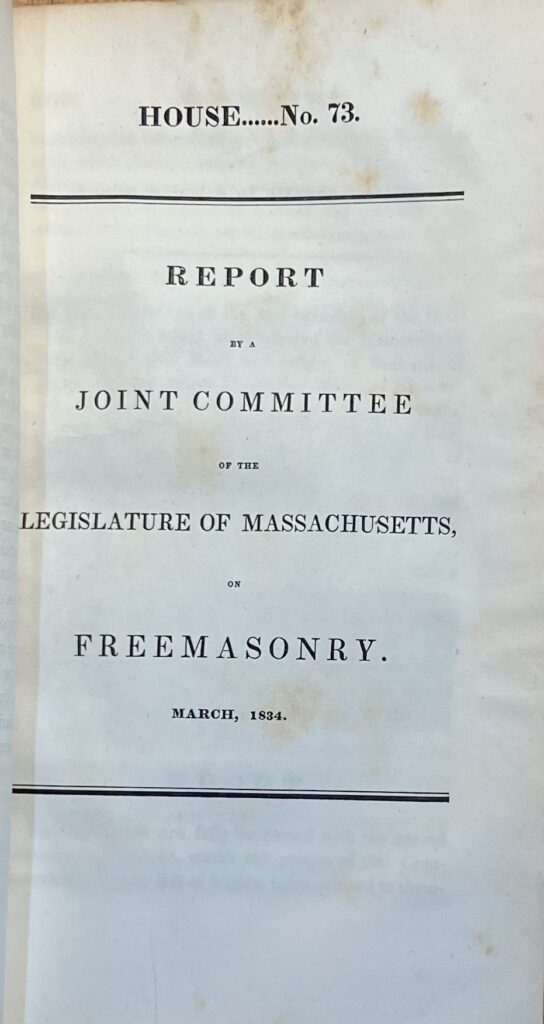

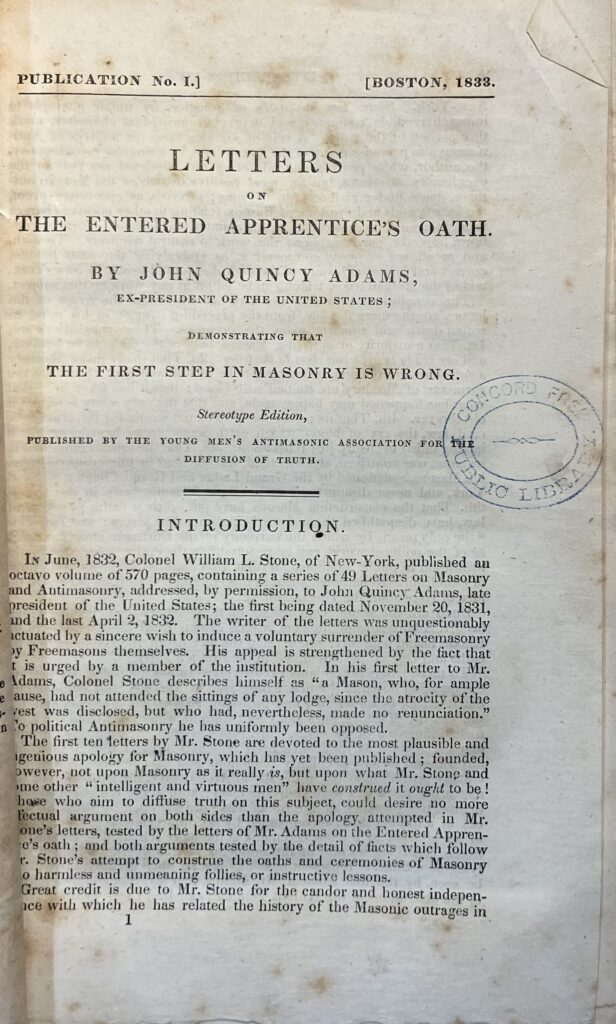

These several volumes, containing thirty-one distinct items, the great majority from the peak years of the conflict, would not attract the notice of most book collectors today. Half-bound in sheep covered with blue paper, they are crammed with a miscellany of materials—addresses to Masonic lodges, speeches by opponents of the fraternity, proceedings of Anti-Masonic conventions, reports of legislative investigations—barely held together after 181 years of peaceful coexistence on library shelves. One volume is labeled “Freemasonry,” another “Masonry & Anti-Masonry,” and the last “Anti-Masonry”; in the library, as in life, the anti’s overwhelmed their foe.