Almost every child in the United States learns who John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson were. They are five men out of a very select group of forty-three (at present count). And certainly many people are also familiar with the names of prominent figures such as John Marshall, Daniel Webster, and Henry Clay—men who were not president, but whose names have been passed down through history textbooks, public statues, and names on streets and schools. Less well known to the general public but appearing frequently in histories of early America are men like Artemas Ward, Timothy Pickering, and Asahel Sterns. These men were all members of the 14th Congress from the northeastern section of Massachusetts. They have their own pages on Wikipedia, and they appear in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, maintained by the Office of History and Preservation of the House of Representatives and the Office of the Historian of the U.S. Senate. Most importantly for the purposes of this essay, they appear in the definitive reference book relied upon by scholars studying past congressional elections—Michael Dubin’s United States Congressional Elections, 1788-1997: The Official Results—which offers vote totals for all elections to Congress up to 1997. But there is one man, and one election, that have been lost to history. This article tells the story of how Daniel White got elected to Congress in 1814, and how everybody forgot about it.

Most people who lived and died in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the United States left little to no trace in the historical record outside of family trees and brief mentions in contemporary newspaper obituaries. But there is also a broad middle ground in history—those who left behind some sort of recorded history that is somewhere in-between, traces that are not easily found through the Web, and instead require digging in archives that haven’t yet been digitized. One of those people is Daniel Appleton White (or Daniel A. White, as contemporary newspapers referred to him), born in the late spring of 1776, just a few weeks before the formal Declaration of Independence, and who died in March of 1861, less than two weeks before the firing on Fort Sumter began the Civil War. There is some information on White that can be found relatively easily, from two memorials written on him—one by request of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1863 and the other at the request of the Essex Institute in 1864 (there is also a collection of some of his papers in the Harvard University Archives). Yet, he is not sufficiently prominent to have earned his own page on Wikipedia, there are scarce traces of him in books published after 1900 (his one mention in The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict is a letter referenced in a bibliographical note), and he has no listing in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. This would not be remarkable, except for the fact that in November of 1814, Daniel A. White was elected to the U.S. Congress from the Essex North District in Massachusetts.

Here is a mystery, which breaks down into several questions.

So here is a mystery, which breaks down into several questions. The first is, if Daniel A. White was elected to Congress in 1814, why is he not listed in the two definitive reference works on members of the U.S. Congress? The second is, if Daniel A. White didn’t serve in Congress, then who did? The third is, if White didn’t serve, then why not? The final question is, why are we only now discovering this fact, some 200 years after the original election?

What happened in November of 1814? Dubin’s collection of data on U.S. congressional elections shows Jeremiah Nelson as the winner of the 1814 election in the Essex-North District. Nelson is listed as receiving 1,810 votes to 205 for Thomas Kitteridge. The Biographical Directory would seem to support this notion with their listing for Nelson: “elected as a Federalist to the Fourteenth and to the three succeeding Congresses and reelected as an Adams-Clay Federalist to the Eighteenth Congress (March 4, 1815-March 3, 1825).” But, if you were to confirm this with the information in the Abstract of Votes for Members of Congress held on microfilm at the Massachusetts Archives, you will indeed find results for the November 1814 election showing returns of 1,810 versus 205 (with 5 scattering votes). The only problem is that Jeremiah Nelson didn’t receive those 1,810 votes. Daniel A. White did.

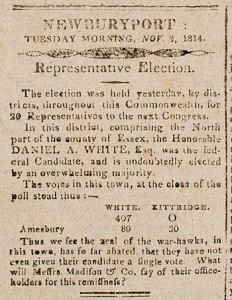

Contemporary newspaper accounts make it clear that White was the Federalists’ chosen candidate in the district in 1814. He was listed as a candidate for Congress from the Essex North District in the October 21, 1814, edition of the Newburyport Herald and Country Gazette, and references to him as a candidate continued to appear in that paper on a weekly basis throughout the fall. Other newspapers in the region refer to his candidacy as well: the Columbian Centinel of Boston, on October 26, October 29, and November 5; and The Merrimack Intelligencer of Haverhill, Mass., on November 5. Both his overwhelming victory on November 7 and his fervent Federalist views were apparent in a paragraph published in the Herald and Country Gazette the next day to accompany the Newburyport vote total in White’s favor of 407-0: “Thus we see the zeal of the war-hawks, in this town, has so far abated, that they have not even given their candidate a single vote. What will Messrs. Madison & Co. say of their office-holders for this remissness?” The abstract of votes indicates that Republican candidate Thomas Kitteridge did, in fact, fail to receive a single vote from Newburyport, and that he met the same fate in Boxford, Hamilton, Topsfield, and South Reading. As can be seen from the election results compiled in the New Nation Votes database, in only two towns in the district did Kitteridge receive so much as a quarter of the vote: Methuen, where he was outpolled by White 101-55, and Amesbury, where Kitteridge received 30 votes to White’s 80.

Thus, it is clear that the absence of White from Dubin’s book is an error. It was Daniel White who received those 1,810 votes. But what about theBiographical Directory—the official government record of members of Congress? White’s absence from that volume is easier to explain: Daniel A. White never served in Congress. The next mention of White in the Newburyport Herald, one of only two newspapers being published in the district at the time, is late in the following spring: “His Excellency has nominated to the Council, the Hon. DANIEL A. WHITE, Esq. of this town, (representative elect to the next Congress,) as Judge of Probate for the county of Essex, vice the venerable HOLTEN, resigned; and NATHANIEL LORD, 3rd, Esq. Register, of Probate, vice DANIEL NOVE Esq. deceased. The Hon. Mr. WHITE, we learn, has accepted the appointment” (June 6, 1815). Though Article I, Section 6, of the Constitution forbids any representative from being “appointed to any civil Office under the Authority of the United States,” there is no specific mention of state offices, though it would certainly have been impractical and extremely difficult to fulfill both positions. While there is no precise mention in the newspapers of his resignation from his congressional seat, he clearly must have done so before June 27, 1815, when the Newburyport Herald printed the following: “NOTICE. The Federal Republicans of Newburyport, are requested to meet at the Town Hall this evening, PRECISELY at 7 oclock to make arrangements for the selection of a suitable person to represent this District in the Congress of the U. States.”

So, the answer to the first question is clear: while White may have won election to Congress, he resigned that seat in late spring or early summer of 1815, long before the Fourteenth Congress convened on December 4.

This bring us to the next question: who did serve as the Essex North Representative to the Fourteenth Congress? The answer, of course, is Jeremiah Nelson, the man listed in Dubin’s book as having received White’s votes and whom the Biographical Directory lists as the winner of the original election. Nelson, born in either 1768 or 1769, was a prominent Newburyport resident from 1793 until his death in 1838. He had already been a U.S. representative once, serving in the Ninth Congress from 1805 to 1807, defeating the same Thomas Kitteridge who would be White’s opponent in 1806 (in fact, from 1800 to 1817, Kitteridge would be the Republicans’ sacrificial lamb in every election, finishing second in every congressional election except 1812, when the Republicans offered no candidate). After his initial term in Congress, Nelson returned to Newburyport and was a town official in 1815 when he was announced as a candidate in the Newburyport newspaper on July 11: “At a meeting of Delegates from the following towns in Essex North District, viz. Dracut, Boxford, Bradford, Ipswich, Haverhill, Topsfield, Newburyport, Salisbury, Rowley, Andover and Newbury, holden at Hill’s Tavern in Newbury, July 10th, 1815, it was unanimously voted to support the Hon. JEREMIAH NELSON at the Election to be made on Monday the 17th inst. as Representative of the said District in Congress, to fill the vacancy occasioned by the resignation of the Hon. DANIEL A. WHITE, appointed Judge of Probate.”

The election was moving at an accelerated pace. There were less than six weeks between the announcement of White’s appointment to the probate court and the election of his successor. (In comparison, in 2013 in my own congressional district, Ed Markey was elected to the U.S. Senate on June 25, in a special election to replace John Kerry, and Katharine Clark was not elected to replace him until December 10).

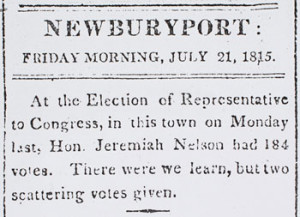

There was almost no news about the election itself. Of the four newspapers in Essex County, one was a Republican paper (the Essex Register) that reported no news of the election at all. The other three were Federalist papers, yet each printed very little in the way of results. The only actual results were from the Newburyport Herald: “At the Election of Representative to Congress, in this town on Monday last, Hon. Jeremiah Nelson had 184 votes. There were we learn, but two scattering votes given” (July 21, 1815). The returns from the other two newspapers gave vague results, but little in the way of actual details. In fact, the Salem Gazette seemed fairly mystified by the entire proceeding: “Last Monday, we had understood, was to be the day for the election of a Member of Congress, instead of Hon. Mr. White, appointed Judge of Probate, and that the Hon. JEREMIAH NELSON was the federal (we presume there no other in this sterling district) candidate. If the election really took place, we believe it was the most silent and quiet one that has been known since our rulers first began to chain us to the fiery car of Bonaparte; for we have heard nothing of its result, and the election is not even mentioned in the Newburyport paper, which came out the day after” (July 21, 1815).

Whatever the other towns may have provided in votes, it was clear that Jeremiah Nelson was now the Congressman-elect from the Essex North District. Since the session had not yet begun, it was Nelson who took his seat in December, and the election of White seemed to have been lost to history at this point. Adding to the disappearance of White’s election was the almost total absence of news on the election to replace him. It is likely that there was little suspense, and thus little interest, in the special election. The Essex North District was so one-sided that the last Federalist to receive less than 60 percent of the vote was when Nelson had run the first time, in 1804. No Republican had ever been elected from the Essex North District, or its predecessor, the Fourth Middle District. What’s more, the election itself had not drawn much in the way of votes, if the results from Newburyport are any indication. While the 1812 and 1814 elections, which were mostly one-sided affairs, had received far fewer vote totals than the more competitive 1808 and 1810 elections, there was still a large drop in the vote total for Newburyport in the 1815 special election. From a high in 1808 of 880 votes, the total had dropped down to 408 in 1814. Yet, this was still more than double the number of votes in the special election, which only drew 184 total votes. In the 1814 congressional race there had only been 2,020 total votes in the district, while the given same towns had 5,299 votes in the governor’s race in the same year. Aside from the matter of low voter interest, there was a much bigger story that was captivating the public’s attention at the time. Nearly every issue of the area papers published, both before and after the election, were full of news about the scandal at Dartmoor Prison in England. Thousands of sailors captured during the War of 1812 were being held prisoner under appalling conditions at the prison on the bleak moors of Devonshire. In April 1815, rumors of an escape attempt led to British guards firing into a crowd of prisoners; the subsequent riot left seven American prisoners dead and thirty-one wounded. This incident was all anyone seemed to care about, and was much bigger news than an election in a lopsided district that could only have one result: the election of Jeremiah Nelson.

A year and a half later, in October 1816, as he was nearing 50, Nelson would decline to run again. As a result, for the first time in the district since 1794, the 1816 election required a second trial (Massachusetts law at the time, as with all of the New England states, required a majority for a winner to be declared in a congressional race). Even in 1794, the race had been between two Federalists. For the first time in living memory, there seemed to be some doubt that the district would send a Federalist to Congress. Yet this was not due to a more robust challenge from Thomas Kitteridge, who again came up short. The problem this time was a lack of unity among the Federalists. The district’s lone Republican newspaper, the Essex Register, took what comfort it could in reporting that the Federalists “have got into a warm quarrel about [Nelson’s] successor, and have two candidates in nomination, viz. Samuel L. Knapp, and Wm. B. Bannister, Esq’rs. Lawyers of Newburyport” (November 2, 1816). With the additional presence of Ebenezer Moseley, another Federalist, in the race, the Merrimack Intelligencer put it succinctly: “Owing to the want of unity in the federal party there will be no choice” (November 9, 1816). A second trial, held in January, had similar results, although Nelson received a scattering of votes. Apparently Nelson’s name had been put back into nomination, according to the January 21, 1817, edition of the Newburyport Herald and Commercial Gazette, which claimed that “we are well assured that Mr. Nelson will serve if elected…” (January 24, 1817). After the second trial, the Federalists did indeed unite behind Nelson, and in the third trial, held in May, he again trounced Kitteridge and returned to Washington.

Nelson would stay in his seat for three more terms, never getting less than 70 percent of the vote. In 1824, he would step down again, and his replacement, John Varnum, would face the closest election in the district’s history, receiving a small plurality of twenty-seven votes in the first election and only getting seven votes more than a majority in the second trial. The election of 1830 featured four candidates, and became the most drawn-out congressional election in U.S. history, not being resolved until over two years after the original election. After the tenth trial, poor Joseph Kitteridge (the son of the persistent Thomas) came closer to Congress than his father ever did, winning 49.01% of the vote, only 35 votes short of being elected. In the thirteenth trial, held on November 12, 1832, Jeremiah Nelson was once again summoned from retirement, and was elected to yet another term in Congress, serving half a term before returning to Newburyport and retiring for good in 1833 (having married late in life, Nelson left four fairly young children at his death in 1838).

Clearly, Jeremiah Nelson is well established in the history books, even if he is hardly a household name. So why, precisely, did Daniel Appleton White decline to serve in Congress?

The quick and easy answer is in those original newspaper articles: that he was appointed judge of probate in Essex County. White was an important enough figure at the time of his death in 1861 that James Walker, the recently retired president of Harvard University, published a memorial to him in 1863. And the pages of that memorial may hold the real reason behind White’s decision: “From 1810 to 1815, Mr. White was a member of the Massachusetts Senate. In that day, for so young a man, this was a high political distinction; but it seems to have had few attractions in his view, except the prospect of serving the public. Indeed, in the beginning, there was one circumstance which made the appointment positively irksome: it drew him away from his family, when they stood most in need of his presence and care; and this apparently to but little purpose, as the government of the State had just passed into the hands of the Democratic party, leaving him in a helpless minority on all the great questions at issue.”

The more likely explanation for White’s decision, however, is simultaneously more prosaic and more personal: he wanted to spend more time with his family. White was a widower, who had been married for less than four years before his wife died in 1811, leaving him with two young daughters. White was understandably not pleased at the prospect of being away from his family as often as a career in Boston would require, a mere forty-three miles away from his home in Haverhill. From Haverhill to the District of Columbia is ten times that distance. At a time when it could take most of a day to travel from Haverhill to the Massachusetts State House, the trip to Washington could easily take more than a week.

Walker expanded on how White’s disposition left him ill-suited to a career in politics: “But we must remember that public life, in itself considered, had no charms for him; and also that the cares and responsibilities of a lawyer in large practice were positively distasteful. A few days after having been admitted to the Bar, he had written to a young friend, ‘last week I took the attorney’s oaths, and was admitted into a profession, the chicanery and drudgers of which I abhor, and fear I always shall.’ Accordingly, we cannot wonder at his accepting a situation which was, beyond question, the most congenial to his nature and habits the law could afford.”

This view of White’s temperament does raise the question of why White would have allowed his name to be put forward as a congressional candidate in the first place. Given the overwhelming Federalist control of the district, he had to know he would be elected. Whether it was due to financial considerations, or the call of public service, White did run for Congress, and perhaps may have been relieved when he was appointed to a position that allowed him to stay in Essex County, much closer to his two daughters. It was the right decision for White, which George Briggs made clear in the memorial he presented at the Essex Institute: “This was the turning point in his life. It was singular, certainly, that a man at the age of thirty-nine, who had already attained marked professional and political distinction, and stood so high in the public favor and confidence, should retire both from the Bar, and from public life, when so wide a sphere of service and influence was open to him.”

The slower rhythms of the probate court were clearly congenial to White, who served on the court for nearly forty years. When he retired in 1853, he had served on the court longer than any person in its history.

This is the point where White seems to have passed out of well-recorded history. He would receive a page in the History of Newburyport Mass., published in 1909, which mentions his election to Congress. His absence from the Biographical Directory is not surprising; the directory doesn’t mention those who were elected to Congress but didn’t serve. His absence from Dubin’s work on congressional elections is clearly an error, as his vote total is attributed to Jeremiah Nelson, who did serve, and whose special election seems to have been mostly lost to history.

All of that raises the final question: why was this election forgotten, and why is all of this finally now coming to light? The absence of the second election is notable primarily because it is also absent from the abstract of votes, kept in the original books at the Massachusetts Archives, but widely available on microfilm. It is, as far as is known, the only congressional election absent from these records. The only known data on the special election held in July of 1815 is from the scant reports in the local newspapers, only one of which contained any actual results. Regardless of why it was overlooked in 1815, it is not in the abstract, and since that has been the primary (and official) source for data on Massachusetts congressional elections, it is no surprise that it came to be lost to history. The existence of the election, however, has now come to light thanks to Philip Lampi and A New Nation Votes, an ongoing collaborative project between the American Antiquarian Society and Tufts University, with funding provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The primary claim to fame for ANNV has been the massive collection of election records all in one place and their subsequent ongoing digitization. Before this project, a historian seeking access to all of this data would have had to visit the archives of some two dozen states as well as scour the history of hundreds of eighteenth- and nineteenth- century newspapers. But Philip Lampi has done the scouring of those hundreds (and thousands) of newspapers himself, over the course of over forty years, collecting a massive amount of information that is uncovering mysteries like the election of Daniel A. White in November 1814.

While gathering data for Massachusetts elections in 1815, Lampi came upon a mention in theNewburyport Herald of a special election in which Jeremiah Nelson received 184 votes. With no special election for Congress on record in the state of Massachusetts in 1815, Mr. Lampi thought this odd, and called me. Looking together at the record in Dubin, checking our microfilm copy of the abstract of votes, and looking at the directory, it soon became apparent what had happened. It was clear that Daniel A. White had won the original election, that he had resigned his seat, and that Jeremiah Nelson had been elected to replace him.

The records for Jeremiah Nelson’s election in 1815 amount to the votes from one town, and the fact of his election. Its absence from the abstract of votes held at the Massachusetts Archives is, as far is known, a singular omission. It is no longer, however, absent from history.

Further Reading

There were two memorials of Daniel A. White published shortly after his death, and these offer the most detail about his career. The first is Rev. James Walker’s Memoir of Hon. Daniel Appleton White. Prepared Agreeably to a Resolution of the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston, 1863), available via Google Books. The second is George W. Briggs, Memoir of Daniel Appleton White.Prepared by Request of the Essex Institute, and Read at the Meeting of January 11, 1864 (Salem, 1864), available via openlibrary.org. White also receives brief mention in John J. Currier’s History of Newburyport, Mass., 1764-1909, Volume II (Newburyport, Mass., 1909).

All of the newspapers referenced can be found at the American Antiquarian Society and are available through the America’s Historical Newspapers project scanned by Readex.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.4 (Summer, 2014).

Erik Beck is the project coordinator for A New Nation Votes, a collaborative project between the American Antiquarian Society and Tufts University, with funding provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities. After two years of data entry, Erik has spent the last four years overseeing the digitization of the Lampi collection, an example of which is highlighted in this article.