Benjamin Carr’s Music Sheets

The composer, performer, printer, and publisher Benjamin Carr (1768-1831) left his native England in 1793 to open a music shop in Philadelphia. His father, Joseph, followed suit a year later, starting a satellite store in Baltimore. Combined with the opening of Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theater early in 1794, Joseph’s arrival secured Benjamin’s success. The father-son team pooled resources, meeting the music-sheet demand that theatrical performances generated. Together with his competitor, George Willig, the younger Carr would issue most of Philadelphia’s printed music between 1793 and 1801, when he turned to other pursuits.

Profitable though it was, Carr’s U.S. publishing career began at a turbulent time. The execution of French King Louis XVI in January 1793, combined with the ensuing Terror and the notorious diplomacy of Edmond-Charles Genet, ended the near-universal enthusiasm with which Americans had greeted the French Revolution. And as Haitian refugees poured into U.S. ports that same year, controversy over Franco-American relations grew. For Carr, whose elite, music-reading clients were often conservative, the publication of radical French songs was, on the face of it, a risky venture.

But the public and oral transmission of French revolutionary song, which fueled early American dissent, was a different matter than its private consumption in music-sheet form. Music’s abstraction from performance, via print, freed it from physical expressions like marching and dancing. And song’s separation from public utterance made it seem less politically charged. Silent arrangements of ink on paper and the salon performances that they enabled were safely removed from the volatile contexts in which French revolutionary song initially flourished.

Carr’s printed music reconciled the three most popular songs of the French Revolution to the cultured climate of Philadelphia’s drawing rooms. To be sure, he was not the first to publish these. They shuttled between sound and print from early on, and Carr in fact based his sheets on existing British ones. But each tune nonetheless had an initial purpose other than singing, which editions like Carr’s obscured. “La Marseillaise,” for example, was a march. Though it displays an artful pairing of melody and lyrics, it was devised to coordinate military movement. For its part, “La Carmagnole” was as a ronde, a popular group dance accompanied by song, and “Ça Ira,” a contredanse, came from the ballroom.

Carr’s editions uncoupled this music from bodily action, but not entirely. Despite their remove from extra-musical function, they remain marked by the march and the dance. I begin with the most inherently songful of the three tunes, “La Marseillaise,” and then consider the more problematic cases of “La Carmagnole” and “Ça Ira.” Finally, Carr’s editions of all three tunes informed his storied Federal Overture (1794), enabling it to transcend Philadelphia’s partisan rancor.

“La Marseillaise”

The music that we know as “La Marseillaise,” a title it acquired in the nineteenth century, was first published in Strasbourg in 1792 as the “Chant de guerre pour l’armée du Rhin” (“War Song of the Rhine Army”). It was written in April of that year by an officer, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, to boost troop morale and accompany their march. A battalion from Marseilles brought the tune to Paris, where in September it became known as the “Hymne des Marseillaise.” At about the same time the song reached London, where various publishers issued it as “The Marseilles March.”

Carr had at least one of the latter sheets to hand when he produced “The Marseilles Hymn” in French and English (“Marche des Marseillois”) in 1793. His and the London editions have identical keyboard arrangements with four English verses based loosely on de Lisle’s. They also separately present the song’s melody with its six original French verses (fig. 1).

Allons enfants de la Patrie,

Le jour de gloire est arrivé.

Contre nous de la tyrannie,

L’étendard sanglant est levé. (bis)

Entendez-vous dans les campagnes,

Mugir ces féroces soldats?

Ils viennent jusques dans vos bras,

égorger vos fils, vos compagnes.

Aux armes, citoyens,

Formez vos bataillons.

Marchez, marchez,

Qu’un sang impur

Abreuve nos sillons.

Marchons, marchons,

Qu’un sang impur

Abreuve nos sillons.

Come, children of the Fatherland,

The day of glory is arrived.

Against us, the bloody flag

Of tyranny is raised. (repeat)

Don’t you hear, in the countryside,

The braying of these savage soldiers?

They come right into your midst,

To slaughter your children, your wives.

To arms, citizens,

Form your battalions.

March, march,

So that an impure blood

Shall water our furrows.

Let’s march, let’s march,

So that an impure blood

Shall water our furrows.

Carr’s score betrays the contradictory impulses at work in “La Marseillaise”—its songful complementarity of music and text, on the one hand, and its military functionalism, on the other. Let me first highlight a few places where the music reflects the meaning of the words. One begins with the seventh line of the text (“Ils viennent jusques dans vos bras”), where the lyrics take a grim turn. Here the music shifts from the buoyant major mode to the sullen minor, which persists until the refrain (“Marchez, marchez”) brings the return of the major mode.

More localized text expression happens on the word “est” (“is”) in the second line of the text, and with the word “mugir” (“braying”), at the beginning of the sixth line. In the first case, although the alignment is unclear in Carr’s printing, “est” is matched with a long, high note. Such emphasis is normally reserved for a more striking word, and here “gloire” (“glory”) would have been a more conventional choice. But instead de Lisle pairs the more important note with the less important word, creating a musical surprise. He thus depicts the arrival of “the day of glory,” which jolts the Fatherland’s children into action.

With the exception of “Mugir ces féroces soldats,” de Lisle begins each line of his text at a rhythmically weak moment. All the other lines start with transient notes, but “mugir” begins with a heavy, sustained tone. Here de Lisle also omits the usual pause between phrases, so that “mugir” seems to arrive early. And he enhances this surprise by altering the pitch of the syllable “mu-” from what is expected. This abrupt melodic change combines with the rhythmic displacement of “mugir” to convey the enemy’s crude braying.

Such examples suggest that de Lisle wrote the words of the first verse before its music, a view that is further supported by his allotment of the same amount of music to each line of text. There is an exception to this, however. About half-way through the score, beneath the words, “La General,” a series of repeated notes imitates a drum. This is an insertion and may have originated in the London source(s) from which Carr copied his edition. The “General” was a rhythmic signal that instructed armies to arise and prepare for the march, so here it amplifies the commands given in the lyrics: “Aux armes, citoyens / Formez vos bataillons.”

Since it did not accompany the march itself, however, the “General” was an artificial addition to de Lisle’s song. Two centuries earlier, the music theorist Thoinot Arbeau had notated the rhythm used to regulate the movement of French armies. It consisted of eight beats, the first five of which were struck, and the last three of which were silent. The first four beats were sounded with one stick, but the fifth was hit with both, creating an accent. This suggests a modern transcription in two bars of duple meter (ex. 1), the same amount of time to which de Lisle assigned each line of his text.

Example 1. Transcription of march rhythm in Thoinot Arbeau, Orchesographie (Langres, 1589).

When repeated, Arbeau’s rhythm forms a pattern with which we can compare de Lisle’s tune (ex. 2). The melody doesn’t follow it strictly—that was the drum’s role. Instead, it provides embellishments that keep the music interesting. But even so, the rhythmic framework is evident. Most of the notes in bars one, five, and seven, for example, correspond with the strokes of the drum. When the drummer rests, the tune becomes rhythmically freer, consisting either of held notes and rests or multiplied activity. In the intervening bars, the pulse is more insistent.

Example 2. Opening quatrain of “La Marseillaise,” as edited by Carr, overlaid with march rhythm.

Eighteenth-century French armies marched at one of two tempos. The pas redoublé, or doubled step, was used for short maneuvers and had a cadence of 120 steps per minute, whereas the pas ordinaire, or standard step, was approximately half as fast. “La Marseillaise” worked with both. If the step was assigned to the quarter note (four per bar), the song served as a pas redoublé. If the step was assigned to the half note (two per bar), then it functioned as a pas ordinaire. Since a regulation step was twenty-four inches, a single verse of “La Marseillaise” represented a walking distance of either 272 or 136 feet.

Even though it was conceived as a song, then, with a tune shaped to represent its words, “La Marseillaise” is marked by the movement of soldiers. In music-sheet form, its ink symbols betray its former embodiment. In 1796, Carr reissued this tune in two collections of nonvocal music, his Evening Amusement and Military Amusement. Once he had made it into a parlor song, it was possible to publish arrangements of “La Marseillaise” that abstracted it not only from extra-musical function, but from verbal meaning, too.

“La Carmagnole”

“La Carmagnole” became popular in Paris at the same time as “La Marseillaise.” It, too, accompanied French army maneuvers and reached America via Britain. But here the comparison falters. “La Carmagnole” was rooted in oral practice and the ronde, a rustic dance in which participants formed a ring around an object like a tree or liberty pole. Dancers circled left and right, moved in and out from the center, and made special steps at melodically marked moments. The sung tune was their only accompaniment. The song had no definitive text apart from its title (which designates a coat imported from Italy by French laborers) and its militant refrain. Verses were often made up on the spot to commemorate local issues and people. Indeed, in the early twentieth century, the head librarian at the French National Conservatory identified more than fifty verses that were paired with the following chorus:

Dansons la carmagnole,

Vive le son, vive le son,

Dansons la carmagnole,

Vive le son, du cannon.

Let’s dance the carmagnole,

Long live the sound, long live the sound,

Let’s dance the carmagnole,

Long live the sound of the cannon.

Given its popular origins, music publishers aiming to cast “La Carmagnole” as an elite diversion faced a challenge—one that Carr’s 1794 edition met head-on. Arranged for solo voice and keyboard, it was copied from an existing London sheet and includes four French verses along with a self-standing version for the guitar (fig. 2).

This sheet departs radically from the renditions of “La Carmagnole” that sounded in the public spaces of Philadelphia. It is framed by an introduction and conclusion for the keyboard, which provides accompaniment throughout. This becomes conspicuous when an out-of-context chord (an A7) appears with the first repetition of “vive le son” on page two, and when this is echoed by an acute dissonance (an F-sharp against a C major chord) during the next repetition of the same text. An amateur keyboardist would have struggled to play this music at the tempo of the dance, so salon performances of “La Carmagnole” were comparatively slow.

Like the music itself, the visual arrangement of Carr’s “Carmagnole” gives the impression of a methodically crafted song rather than an unrefined, semi-improvisatory dance. For the already songful “Marseillaise,” it sufficed to combine the voice and keyboard on a double staff. The vocal part of “La Carmagnole,” by contrast, is printed separately from the keyboard part, on a third staff. This makes it look independent, even though the keyboard mostly doubles it. For part of page two (the second line of combined staves), however, the melody is entrusted to the voice alone. “La Carmagnole” was thus changed from a vocally accompanied dance into an instrumentally accompanied song.

Verses for “La Carmagnole” were short and simple. The most famous ones took aim at Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI:

Madame Veto avait promis (bis)

De faire égorger tout Paris, (bis)

Mais son coup a manqué

Grâce à nos canonniers.

Monsieur Veto avait promis (bis)

D’être fidèle à son pays,(bis)

Mais il y a manqué;

Ne faisons plus quartier.

Mrs. Veto had promised (repeat)

To slaughter all of Paris, (repeat)

But her coup has failed

Thanks to our gunners.

Mr. Veto had promised (repeat)

To be true to his country, (repeat)

But he has failed;

Let’s show no mercy.

But these didn’t make it into Carr’s edition, which begins more generically:

Le cannon vient de résonner, (bis)

Guerriers soyons prêts à marcher. (bis)

Citoyens et soldats

En volant aux combats.

The cannon have sounded, (repeat)

Warriors are ready to go. (repeat)

Citizens and soldiers

Are flying into combat.

The repetition of each line in the opening couplet reflects the call-and-response manner in which it was originally performed. Parallel musical units are normally assigned to such repeated text, but not in this case. The first statement of “Le cannon vient de résonner” is set to a lilting tune whose rhythm matches the words. We expect this to be answered by a unit of the same length (as in ex. 3a), but it is instead followed by an extended phrase, with which it forms an asymmetrical pair (ex. 3b).

Example 3a. Expected setting of opening text repetition in “La Carmagnole.”

Example 3b. Setting of opening text repetition in “La Carmagnole,” as edited by Carr.

Example 3a is fictional and shows a symmetrical response to the initial statement. The main difference between this normalization and the phrase as it appears in Carr’s edition is the placement of the word “de.” In example 3a it is assigned to a fleeting note, but in example 3b it is emphasized by duration and by placement on a strong beat. Carr is not to blame for this faulty accentuation, though, because the “Carmagnole” tune wasn’t devised to suit its text. Although we don’t know what the step entailed, this otherwise unaccountable phrase must have accompanied a distinctive moment in the “Carmagnole” dance.

Along with “La Marseillaise,” Carr included the melody of “La Carmagnole,” without words, in his Evening Amusement of 1796. And he later reissued the texted version from the plates he had made in 1794, including it in his Collection of New and Favorite Songs(ca. 1800). He thus published it one time less than he would “Ça Ira.”

“Ça Ira”

Like “La Carmagnole,” “Ça Ira” originated as a social dance, albeit a more sophisticated one. Composed by a Parisian theater musician named Bécourt, it was initially called “Le Carillon National” and its earliest known printing is an arrangement for two violins. As a contredanse, “Le Carillon” had roots in the English country dances (which, despite their name, were genteel) introduced at the court of Louis XIV, and was performed by four couples in a square formation. The music was played through four times, giving each pair a chance to lead. Among the dance figures indicated in an early Paris edition are the rigaudon, pirouette, hand-turn, and English half-chain. Like all contredanses, “Le Carillon” is in rounded binary form, meaning that it has two musical sections, the first of which returns after the second.

This dance became a song during the early French Revolution. Its verses were as varied as those of “La Carmagnole,” but it had a consistent refrain, set to a repetitive tune:

The original verses were devised by a street singer named Ladré, and became popular during preparations for Paris’s Fête de la Fédération of July 1790. The first one was as follows:

Ah! Ça ira, ça ira, ça ira,

Le peuple en ce jour sans cesse répète,

Ah! Ça ira, ça ira, ça ira,

Malgré les mutins tout réussira.

Nos ennemis confus en restent là,

Et nous allons chanter “Alléluia.”

Ah! Ça ira, ça ira, ça ira,

Quand Boileau jadis du clergé parla,

Comme un prophète il a prédit cela;

En chantant ma chansonette,

Avec plaisir on dira,

Ah! Ça ira, ça ira, ça ira.

Oh, it’ll turn out well,

The people on this day incessantly repeat,

Oh, it’ll turn out well,

Despite the mutineers, all will succeed.

Our enemies remain confused,

And we shall sing “Hallelujah.”

Oh, it’ll turn out well,

When Boileau spoke of the clergy,

Like a prophet, he predicted as much;

By singing my little song,

With pleasure you’ll say,

Oh, it’ll turn out well.

By default, songs have one note per syllable of text. Because Bécourt wrote his melody for nonvocal instruments, however, it has stray notes that don’t correspond to the lyrics. This becomes a problem when setting the second line of Ladré’s text, a likely solution to which is shown in example 5a. At least one Parisian printer had other ideas, however, as seen in example 5b.

Example 5a. Plausible alignment of “Le peuple en ce jour sans cesse répète” in “Ça Ira.”

Example 5b. Alignment of “Le peuple en ce jour sans cesse répète” in “Ah! Ça Ira” (Paris: Frère, 1790).

In the same Paris edition, the assignment of text to music becomes altogether haphazard at times. Example 6 shows three successive settings of the phrase, “Ça ira,” each of which differs in terms of rhythmic emphasis, and none of which is desirable when compared to example 4.

Example 6. Indiscriminate accentuation of “ça ira” in “Ah! Ça Ira” (Paris: Frère, 1790).

Bécourt’s tune resists songfulness in further ways. The simplicity of its opening phrase is both a virtue and a vice: it is rhythmically memorable but has almost no melodic interest. A bigger problem, however, arises from the fact that Bécourt wrote his melody without consideration for the range of the human voice. In its original form, it reaches from a low G (near the bottom limit for a bass or alto) to a high B (near the upper limit for a tenor or soprano). This led the foremost historian of French revolutionary song to describe “Ça Ira” as unsingable, but we know that it was sung nevertheless. Performances of “Ça Ira,” especially those by popular crowds, therefore edged closer to rhythmic shouting than to song.

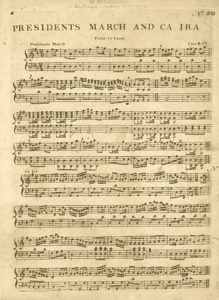

Such considerations deterred Carr from publishing “Ça Ira” in an arrangement for voice and keyboard, in the manner of “La Marseillaise” and “La Carmagnole.” As far as we know, he never issued it with lyrics. The challenge of transforming a dance with revolutionary words into an urbane song, while considerable in the case of “La Carmagnole,” may have seemed insuperable in the case of “Ça Ira.” Carr’s first edition of it, from 1793, was an arrangement for solo keyboard, which he combined on a single page with Philip Phile’s “President’s March” (fig. 3). He later reproduced the melody alone in three different collections: the Philadelphia Pocket Companion (1794), Gentleman’s Amusement (1795), and Evening Amusement (1796).

In each of these editions, Carr presented “Ça Ira” as a wordless, instrumental arrangement of a popular song, but it remains marked by its origins as a dance. In figure 3, notice that the tune begins (half-way down the page) with an incomplete bar. The music itself doesn’t suggest this. It makes more sense, in fact, to notate the opening melody this way:

Example 7. Re-notated opening of “Ça Ira.”

Carr’s unusual barring owes to the song’s history as a contredanse, and more specifically to a convention known as “dancing across the bar.” Opening on the weaker, second half of the bar accommodated an upward motion of the hand or foot, which was then lowered in accordance with the downbeat.

The most popular tunes of the French Revolution resisted the identity of song as a self-standing form of vocal expression: “La Marseillaise” betrayed the movement of soldiers, the music and words of “La Carmagnole” were bent to accommodate the dance, and “Ça Ira” was better suited to the rhythmic chanting of the crowd than the cultured singing of the drawing room. It is thus no surprise that Carr’s next treatment of this music took nonvocal form. The Federal Overture was a fitting culmination to Carr’s career as a publisher of French revolutionary song, for it brought “La Marseillaise,” “La Carmagnole,” and “Ça Ira” together in a single, wordless work. Though it represents a different genre, it advances the same purpose seen in his other editions—broadening the appeal of an otherwise partisan repertory.

The Federal Overture

Carr’s Federal Overture was premiered by an orchestra at Philadelphia’s Southwark Theater in September 1794 and issued in a keyboard arrangement two months later. He composed introductory, transitional, and closing material for this work, which was otherwise an arrangement of nine existing melodies, and exemplified the British genre of the medley overture. It had a uniquely American purpose, however, which was to preempt the disorder that could erupt when theatergoers didn’t hear their favorite tunes. It featured Federalist favorites like “Yankee Doodle” and “The President’s March,” along with the songs we’ve been considering.

The idea of uniting ideologically opposed pieces in a single publication was not unique to the Federal Overture, as figure 3 suggests. Nor was pairing tunes like “The President’s March” and “Ça Ira” necessarily a conciliatory gesture. As the historian Liam Riordan has argued, the Overture appealed to Republican taste while subtly validating Federalism. Its title suggests as much, but, according to Riordan, Carr also musically affirmed the status quo. His newly composed material lent a menacing quality to the French selections while foregrounding “Yankee Doodle” and “The President’s March.”

Carr’s other editions of French revolutionary song don’t underscore Federalism in this way. But they did separate music from public utterance and from social actions like marching and dancing, and these trends continued in the Federal Overture. Carr’s orchestral score for the Overture hasn’t been located, so we only have the keyboard arrangement (along with an abridged version for flute duet, shared between the fifth and sixth numbers of Carr’s Gentleman’s Amusement) to compare with his other publications. The three discussed here were issued before the Overture—”The Marseilles Hymn” and “Ça Ira” in 1793 and “La Carmagnole” by June 1794. Even in the absence of its original performing version, however, it is clear that Carr’s medley further removed this music from the functions it formerly knew. His earlier editions had made it into a parlor song (or a keyboard solo in the case of “Ça Ira”), but now it became a nonverbal orchestral symbol.

In his first edition of “La Marseillaise,” for instance, Carr reserved the eighth-note beam for cases when multiple notes were assigned to a single syllable. He abandoned this vocal consideration in the Overture, however, where the tune also appears in a fuller texture and with a new, symphonic accompaniment in the chorus. For their part, Carr reconceived the melodies of “La Carmagnole” and “Ça Ira” for a nonvocal instrument. Each ascends in the Overture to an E above the treble staff—well beyond vocal range. In addition, “Ça Ira” is realigned so as to begin with a complete bar, and the harmonic complexity of the “Carmagnole” accompaniment is curtailed, although its introductory and closing material is retained. He also added orchestral volume contrasts to each number, according to the conventions of instrumental theater music.

Carr’s editions initially distanced “La Marseillaise,” “La Carmagnole,” and “Ça Ira” from public utterance, turning them into private amusements. But his Federal Overture restored these songs to the public in a carefully managed and wordless form. His political ambition in doing so shouldn’t be exaggerated—he was selling music. But Carr’s publications did soften the radicalism of French revolutionary song, if only to make it more palatable to drawing-room and theater-going consumers alike.

Further Reading

On the role of French revolutionary song in early American popular culture, see Simon Newman, Parades and the Politics of the Street: Festive Culture in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia, 1997). Laura Mason’s Singing the French Revolution: Popular Culture and Politics, 1787-1799 (Ithaca, 1996) and Constant Pierre’s Hymnes et chansons de la Révolution (Paris, 1904) are indispensable studies of the same music across the Atlantic. For more on Carr and musical print, see Richard Wolfe’s Early American Music Engraving and Printing: A History of Music Publishing in America from 1787 to 1825 (Urbana, 1980) and Oscar Sonneck’s Bibliography of Early Secular American Music, 18thCentury, revised and enlarged by William Treat Upton (New York, 1964). On European and American military music of the period, see Raoul Camus, Military Music of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, 1976).

Liam Riordan’s “‘O Dear, What Can the Matter Be?’: The Urban Early Republic and the Politics of Popular Song in Benjamin Carr’s Federal Overture” appears in the Journal of the Early Republic 31 (Summer 2011). For more on the politics and music of the theater, see Heather Nathans, Early American Theatre from the Revolution to Thomas Jefferson: Into the Hands of the People (New York, 2003), and Susan Porter, With an Air Debonair: Musical Theatre in America, 1785-1815 (Washington, D.C., 1991).

Carr’s “Marseilles Hymn” and “President’s March and Ça Ira” are available online in the Johns Hopkins University’s Lester Levy Collection of Sheet Music. There are recordings of “La Marseillaise,” “La Carmagnole,” and “Ça Ira” on Youtube, but they don’t specifically reflect Carr’s editions. Patrick Gallois and the Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä’s 18th-Century American Overture (Naxos, 8.559654, 2011) features an orchestral reconstruction of the Federal Overture.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

Myron Gray is a PhD candidate in music history at the University of Pennsylvania. His dissertation considers the relationship of Philadelphian music to Franco-American politics between 1778 and 1801.