To start at the ending: in the conclusion to Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Piketty suggests the book had been a presentation of “the current state of our historical knowledge concerning the dynamics of the distribution of wealth and income since the eighteenth century.” The documentation for this kind of historiography distinguishes Piketty’s text. The book is an interpretation of an unprecedented amount of historical numerical data, a collection “more extensive than any previous author has assembled,” but inevitably “imperfect and incomplete.”

To speak of the imperfection and incompleteness of numerical data about the life of capital in the twenty-first century is, for Piketty, a way of speaking about the work of the economist. The data have no inherent purpose, and will only do the work to which the economist puts them. Here they allow him to model a study that can disrupt the “intellectual and political debate about the distribution of wealth [that] has long been based on an abundance of prejudice and a paucity of fact.” Piketty wants the book to have a motivating effect, and become material for “lessons [that] can be drawn for the century ahead.” The economist uses numerical data as evidence, but it is not his job to “produce mathematical certainties” that would “substitute for democratic debate.” Economics looks like political economy again: the people are back in it.

The book insists from the very beginning that its narrative about capital is an alternative to the Marxist eschatology ruled by the “principle of infinite accumulation.” This kind of narrative would have arrogated a whole world to itself, until it did away with the world altogether. Having avoided the “Marxist apocalypse,” we find, however, that the “distribution of wealth is too important an issue to be left to economists, sociologists, historians, and philosophers. It is of interest to everyone, and that is a good thing.” Apocalypse averted, the post-apocalypse still seems deeply fascinated with the tendency of any “market economy based on private property, if left to itself,” to create “powerful forces of divergence which are potentially threatening to democratic societies and to the values of social justice on which they are based.”

Drawing on the new, transnational, numerical historical facts, Piketty argues there are economic forces at large in the world that create the discrepancy between the rates of return on capital and the rates of growth of income and output. “The inequality expresses a fundamental logical contradiction,” Piketty argues. This seeming paradox allows old wealth to grow faster than output and wages: this is how “the past devours the future.” The consequences of such logic of wealth distribution are “potentially terrifying,” the more so because the financial dynamic is now impeccably documented. Perhaps we are not past the apocalypse just yet.

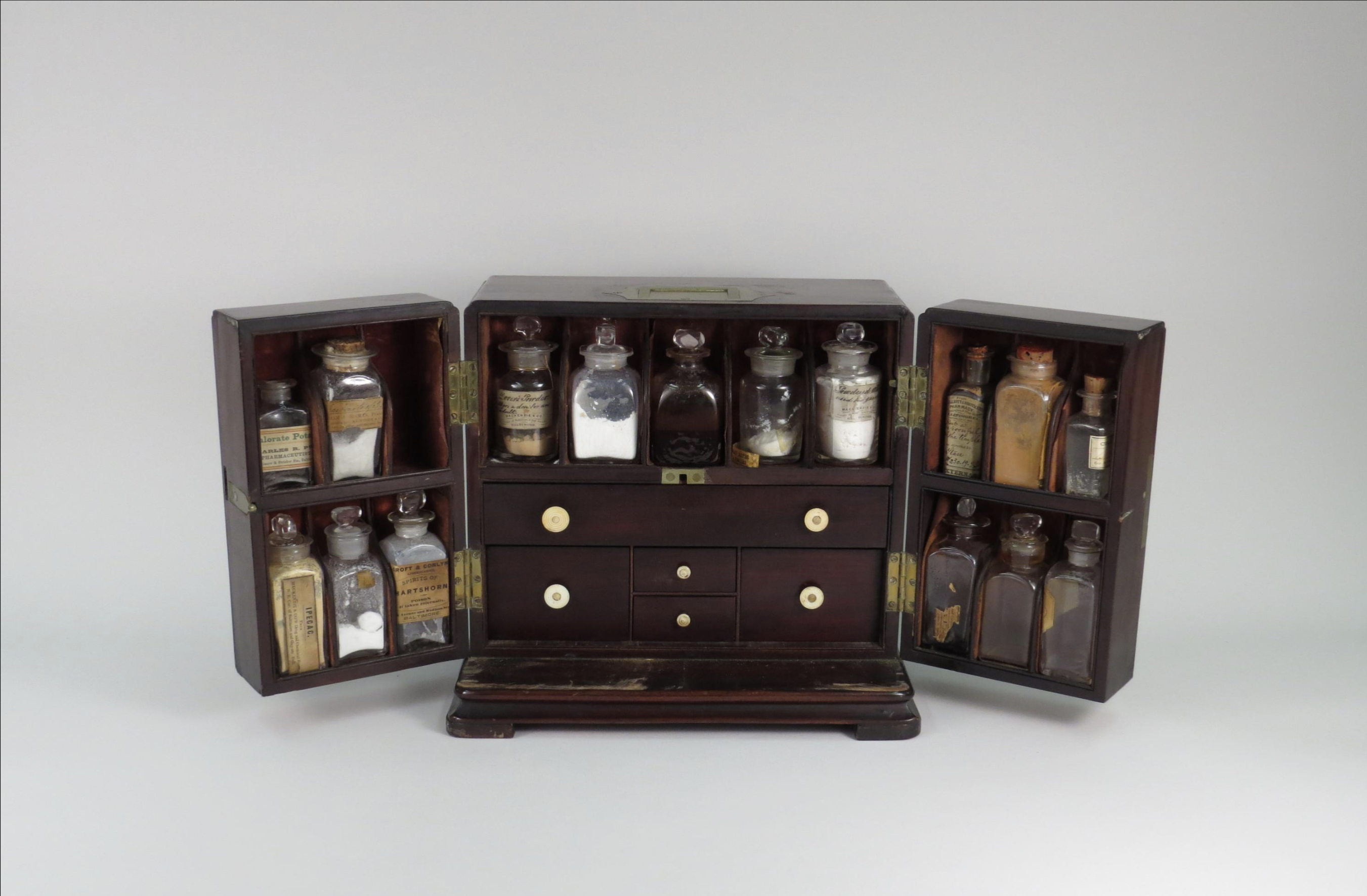

What are these unspeakable terrors lurking beyond the curve? Unprecedented in depth and volume, the data index the significance of new technological powers available to researchers with a new kind of work to do. They are no longer just looking at comparative information on income and taxation from disparate national markets (the somewhat unexhilarating area of Piketty’s “primary” academic expertise). Piketty aspires to refurbish earlier narratives that have treated capital and capitalism as a political and social force field intrinsically related to what Piketty calls the “ideal society.” He marks the work of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writers about the movement of capital (Marx, Ricardo, Malthus, Smith, Locke) as the work of storytellers whose claims about the workings of capital could be read as imaginative and representative, speculative and predictive. Piketty argues that the technological powers that generate the data, and their global reach, redeem these old narratives from their speculative insecurities, and re-assert the ethical dimension of writing about money (fig. 1).

Capital offers to use numerical data to redeem the powers of prophecy by empiricism. Numbers become a kind of thick description that transforms the nature of reference: all who agree to read these statistics the right way can have a glimpse of the shared (terrifying) future. Then the data can become a synthetic and synoptic body of evidence for the existence of the global process the book plots out. We can now claim to see the future of “everyone,” and this is why “everyone” should care. Seemingly boring volumes and genealogies of numerical information lend credence to a catastrophic social and political future that will grow from our economic history and the present.

Capital is a great narrative about the cost of ambivalence about reading science as prophecy, or numerical representation as mythology, when all are understood to be social and historical discourses. If read correctly (as “terrifying”), this twenty-first-century story about capital should propel “everyone” not just to become interested in the adventures of capital, but to act on their new knowledge. But how are readers to know that this is a book about them? Even if they can see the same future from the same numbers, how will they be saved from (the fear of) becoming the victims of capital? Piketty explains that the rate of return on capital now grows irrespective of the actions of its owners. Quite frequently the owners need do nothing at all, such that it looks as if capital moved itself, an agent in its own right, seamlessly conjoined with culture, nation, and social policy. And yet this movement is generated by precisely the “society” whose institutions, labor laws, and assessments of risk and profit create its trends. Readers’ interest and actions would be meaningful in the context of the democratic society that wants to see and mitigate the “strangeness” of the logic of capital accumulation. But who can plot for a more ideal society when, in the immortal words of Margaret Thatcher, there is no such thing as society?

It is revealing then that, to correct the “logical inconsistency” of wealth inequality, Piketty recommends the implementation of a “global capital tax.” In order to treat taxation of capital socially and politically the way capital usually likes to treat itself, the global tax would disregard the borders of nation states, much like capital and its owners do in the pursuit of new markets. This tax assumes that a fundamentally different relationship between the financial and the socio-political is still possible—that there are people still in there.

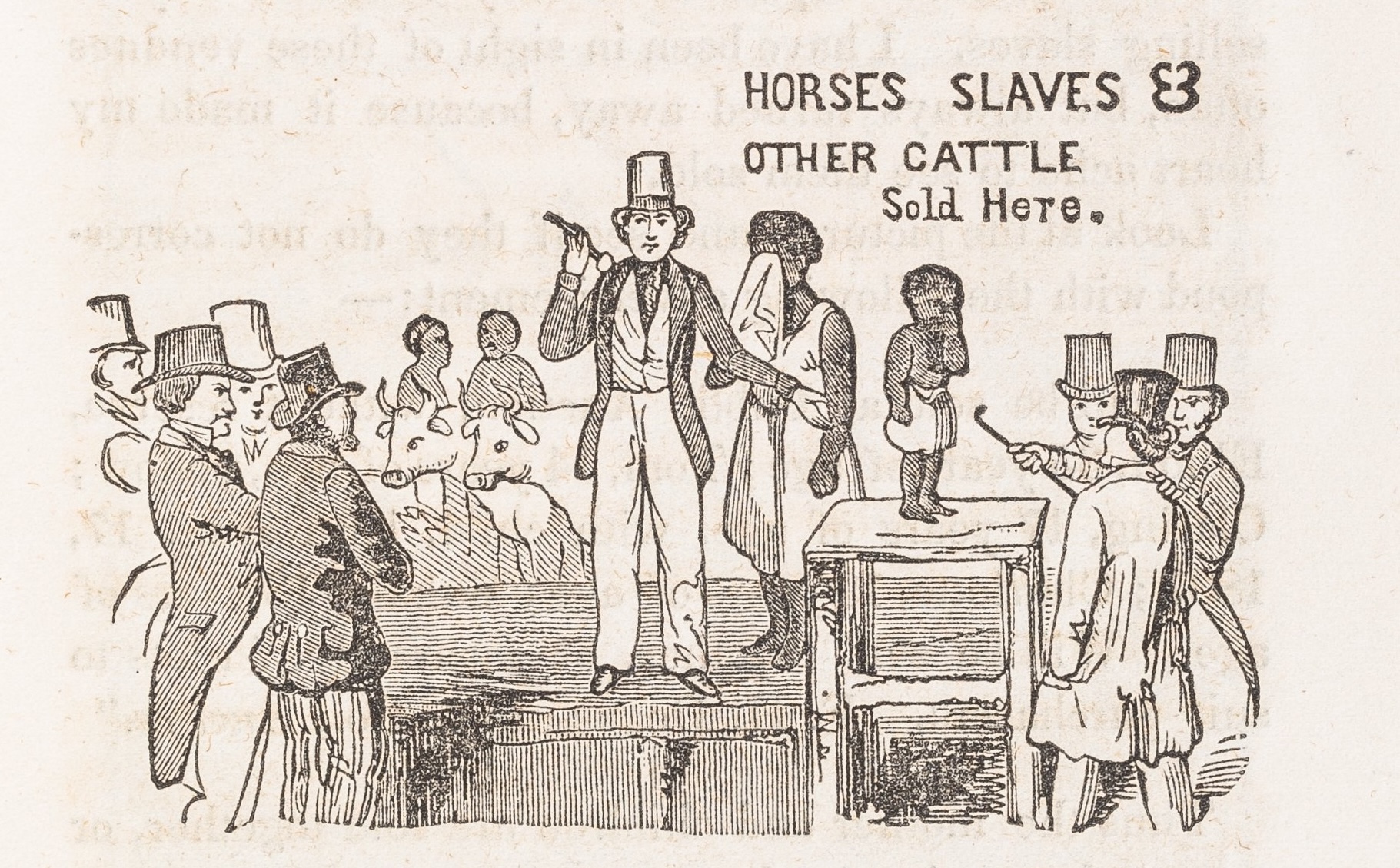

But this ideal is not to be, or not just yet. Capital remains unconcerned with even wealth distribution precisely where its definitions of the social are confined to those that serve the nation state, that is, where it shows itself not to be the origin or a natural byproduct of democracy. It implements national borders, denies legal protections, restricts access to living wage, and unfurls militarized law enforcement against “economic migrants” (fig. 2).

A stark reminder of the socio-political entanglements of capital, the ongoing refugee crisis has pushed millions from regions decimated by lethal political violence. The violence followed unchecked depletion of natural resources, coordinated by global political and economic systems glad to unsee the origin of their propulsion fuel. Drifting away from these destroyed (post)colonial national economies (can it ever be only one?), the refugees negotiate administrative and physical barriers to their migration toward imagined centers of more equitable capital distribution in Europe’s North and West. As they attempt physically to approach their fantasies of a more ideal society, the migrants learn, as Slavoj Žižek puts it, that “‘there is no Norway,’ even in Norway.” It’s as though everybody is in the future already.

Then we can only start at the ending. Thick numerical description concerns “everyone” only if “everyone” had been waiting for numerical facts to issue their prophecies about what may befall “everyone” in a society that needs few people in it to make its money. We should not forget how prophecies were made from the insight and knowledge prior to the abstraction of data sets, about the way money and people have treated each other in the flesh. Saree Makdisi tells us in Romantic Imperialism that William Blake already spoke like a prophet without numbers, 200 years ago, when he versified about the power of the formal logic of global capitalism to forge the manacles of modern subjects’ experience across a “Universal Empire.” Some it enslaved, some it made into indigent children who could fit in a chimney that needed cleaning, and some into “aged men wise guardians of the poor.”

Readers of Piketty’s Capital could do worse than to learn from readers of the gothic about the frustration of reading and writing about a kind of reality nobody else can or wants to see. It is a description of an unnatural order of things that feels familiar nonetheless. Such a reality is terrifying, and reading about it is only stupid if one insists on knowing only one language and only one way to read. Forces greater than those of visible society, and greater than the observable masses of people and numbers, shape this reality and this reading. Right now, at the end, one must learn to imagine how else to know them and how to live with them.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3 (Summer, 2016).

Olivera Jokic is associate professor of English at John Jay College of the City University of New York. She writes and teaches about gender, colonialism, and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature, and about their relationship to histories of writing and methodologies of textual interpretation.