Lyman Beecher on religion and politics in America

The political atmosphere was charged with issues of religion and morality. Regardless of the Constitution’s prohibition of any religious test for office holding, candidates’ spiritual lives and professions of faith came in for extended discussion and scrutiny. The political parties sought to bring religious voters into their coalitions, especially the large number of Americans who identified themselves as evangelical Protestants. Ministers thundered from their pulpits, although sometimes inadvertently wounding their preferred candidates with their utterances. Some asserted that America was a “Christian nation,” while others clamored for religious freedom, and sparks flew from the friction between Protestants and Catholics. Hot-button moral issues polarized the electorate, and a war that some decried as unjustified and downright immoral exacerbated tensions.

Sound familiar? At a forum of Democratic candidates in the summer of 2007, both Senator Hillary Clinton and former Senator John Edwards spoke of the importance of prayer, forgiveness, and how their Christian faith helped them through the most trying times of their lives. On the Republican side, the presence among the leading contenders of a Mormon (Mitt Romney) and a former Southern Baptist pastor (Mike Huckabee) elicited a further outpouring of discussion about the relevance of a candidates’ religion to his or her qualifications for the Oval Office. The two eventual nominees, Senators John McCain and Barack Obama, have both written in some detail about their religious experiences. In Faith of My Fathers, McCain wrote about how faith in God helped him survive imprisonment and torture during his Vietnam War captivity, and he movingly described a makeshift Christmas service he and his fellow P.O.W.’s put on in 1971. For his part, Obama took the title of his book, The Audacity of Hope, from a remark by his pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright Jr. He devoted a thoughtful chapter to religion and politics, in which he discussed his identification with the black church and his decision to join Chicago’s Trinity United Church of Christ.

The McCain and Obama campaigns have also had to work to contain damage caused by their engagement with religious themes. McCain caught flak for the perceived anti-Catholic comments of Texas megachurch pastor and televangelist, the Reverend John Hagee, who had endorsed McCain, while Obama had to repudiate Reverend Wright for a bevy of incendiary remarks. The two candidates also made trouble for themselves. McCain had to backpedal and explain himself when he said that the United States is a “Christian nation,” and Obama drew a barrage of criticism when he opined that “bitter,” working-class Americans “cling to guns or religion” along with nativism and protectionism.

Of course there is nothing new about the politicization of religion (and vice versa) in the United States. In fact, contrary to popular myth, there is nothing at odds with the Constitution about all this. Whatever the first amendment may say about the separation of church and state, religion has had a place in American politics, for better or worse, since the very founding of the nation. Perhaps no early American is more emblematic of this long-standing entanglement of religion and politics than the early nineteenth-century clergyman Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) (fig. 1). Today, Beecher is probably best known for his remarkable brood of children, who included the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the celebrity preacher, writer, and lecturer Henry Ward Beecher. Yet in his generation, Lyman Beecher was one of America’s most prominent clergymen. He was a revivalist during the Second Great Awakening, one of the organizers of innovative missionary and reform organizations such as the American Bible Society and the American Temperance Society, and a seminary president, to name just a few of his career highlights. In all of these very public roles, and many others, Beecher navigated the often perilous path between power and belief, religion and politics. A brief exploration of Beecher’s political experiences may thus allow us to see the present religion-politics matrix with a deeper and clearer perspective.

Lyman Beecher was born and raised in Connecticut and studied for the ministry at Yale. Religion and politics had historically been closely intertwined in that former Puritan colony, and taxpayer funds would subsidize the Congregational churches until 1818. Beecher assumed his first pastorate in 1799 over the Presbyterian Church at East Hampton, New York, just across Long Island Sound from Connecticut. At that time, many of his colleagues in the New England ministry bitterly opposed Thomas Jefferson, the Democratic Republican candidate for the presidency. Jefferson, they believed, had demonstrated a disturbing sympathy for atheistic, anti-clerical views with his insistence on the separation of church and state—articulated in his famous “Virginia Statute on Religious Freedom”—and his association with the likes of Tom Paine and other known religious skeptics.

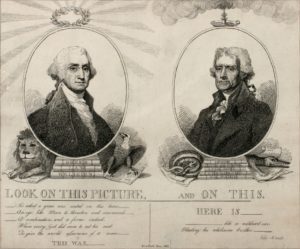

To counter these apparent “infidelities,” the New England clergy unsuccessfully agitated for what one historian has termed “a voter-imposed religious test” that would override the Constitution’s prohibition of religious tests for government office. Figure 2 shows the kinds of invidious comparisons they drew between the piety and wisdom of George Washington and the irreligion of Jefferson. They pointed out, for example, that in his Farewell Address Washington had stated that “reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle,” while Jefferson, in Notes on the State of Virginia, had written that “it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

Within this contentious, partisan atmosphere, Beecher first made a name for himself by denouncing the practice of dueling, especially on the part of seekers of public office. Not long after Aaron Burr’s killing of Alexander Hamilton, Beecher preached a sermon asking how anyone could vote for a murderer. He delivered the sermon at a few Long Island churches during 1805 and at a presbytery meeting in April 1806, and then published it as The Remedy for Duelling. To counter these sorts of unchristian methods, Beecher advocated a ballot-box solution in which Christians would sanctify the electoral process “by withholding your suffrages from every man whose hands are stained with blood, and by intrusting to men of fair character and moral principle the making and execution of your laws.” Beecher lived in an era of partisan polarization, and yet he claimed that his strategy was above party. “It is in vain to cry out ‘priest-craft’—or ‘political preaching,’” he said. “The crime we oppose is peculiar to no party.” Instead, displaying his talents as an activist and organizer, Beecher called upon “voluntary associations” to organize a “concert of action” to suppress the culture of dueling.

Following a move in 1810 to the more lucrative pulpit of the Congregational Church in Litchfield, Connecticut, Beecher continued to push for action by voluntary societies, which he termed “a sort of disciplined moral militia.” He attacked Sabbath breaking and drunkenness in an 1812 sermon entitled, “A Reformation of Morals Practicable and Indispensable.” In his Autobiography, Beecher recalled that he had first become concerned about the problem of alcohol abuse during his time in East Hampton when he observed how unscrupulous merchants plied the Montauk Indians with liquor. He also noted that even when clergymen gathered for such an event as an ordination, they happily imbibed substantial quantities of booze. Now he took a place in the vanguard of the temperance movement, the campaign to get drinkers to swear off at least hard liquor, if not every type of alcoholic beverage. Beecher had a keen appreciation for the necessity of working to change public opinion in order to bring about lasting change. Indeed, over the quarter century between 1825 and 1850, the temperance movement succeeded in slashing the alcohol consumption of the average American adult from seven gallons per year to fewer than two.

This success should not, however, lull us into thinking that policy and belief achieved some sort of easy alliance in nineteenth-century America. Beecher and his clerical peers endured some very difficult days. In support of New England’s commercial economy, for example, they opposed the relatively popular War of 1812. And in their own vineyard, they faced growing competition from rival sects, particularly the Baptists, who called for the separation of church and state. The successful end of the war in 1815 brought disgrace to the anti-war Beecher and his peers in the Federalist Party, substantially weakening their sway in state politics. The result was a sea change in the religious politics of New England. Now the old “Standing Order” of Congregational clergy and New England’s political elite found itself in the minority, unable to stem the tide of disestablishment sentiment. By 1818, Connecticut had formally disestablished the Congregational Church. Beecher realized that the church-state arrangements of the Puritan forefathers were gone for good, and at first he hung his head in gloom. Yet he soon came around to the conclusion that disestablishment was “the best thing that ever happened to the State of Connecticut. It cut the churches loose from dependence on state support. It threw them wholly on their own resources and on God.”

In sermons delivered during the late 1810s and 1820s, Beecher rethought the proper connection between religion and politics in a democratic society. He tried to chart a course between the pitfalls of partisanship and the promise of moral influence. In an 1823 sermon, The Faith Once Delivered to the Saints, he told his listeners to avoid “things merely secular” and to speak out only on “great questions of national morality.” He warned Christians not to get too attached to any political party but rather to cast their votes strictly on the basis of righteousness. As he phrased matters in an 1826 sermon to the Connecticut legislature, “Multitudes of Christians and patriots have long since abandoned party politics, and, not knowing what to do, have abandoned almost the exercise of suffrage. This is wrong. An enlightened and virtuous suffrage may, by system and concentration, become one of the most powerful means of promoting national purity and morality.” In other words, Beecher envisioned the evangelical community as an electoral arbiter that would stand between the political parties and base its judgments solely on moral principles.

Beecher applied these ideas during the Sabbatarian campaigns of the 1810s and 1820s. Sabbatarians wanted to stop the transportation of the mail on Sundays and close the post offices on that day. They believed that the republican experiment depended on Sabbath observation, because that was when the citizenry learned the moral virtue required of them in a free society. In 1814 Beecher became involved in a Presbyterian petition drive that beseeched Congress to halt postal transportation on the Sabbath day. Congress, however, judged the everyday movement of the mails too important to the communication of commercial and military information and so took no action. In 1828, Beecher, now pastor of Boston’s Hanover Street Church, was present at the inaugural meeting of the General Union for Promoting the Observance of the Christian Sabbath, an organization made up of people who promised to honor the Sabbath and boycott transport firms that violated it. He penned the organization’s initial statement, one hundred thousand copies of which were printed and distributed nationwide, followed by a second petition campaign.

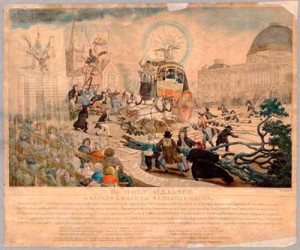

The anti-Sabbatarian opposition that emerged showed that the introduction of supposedly nonpartisan moral issues into politics would prove deeply divisive. Individuals and denominations suspicious of an overly powerful clergy pushed back, especially those like the Baptists who feared that any mixing of church and state—such as that required by government action on behalf of the Sabbath—would favor their rivals, the Congregationalists. As early political cartoons made clear (fig. 3), these fears were quite widespread. The second petition drive was quashed in a Senate committee led by Richard Mentor Johnson, Democrat of Kentucky (fig. 4). The committee took a hands-off approach to the Sabbatarians’ petitions, saying that it was not for the committee to decide whether the Sabbath should be on Saturday or Sunday. The committee also made a slippery-slope argument, suggesting that if Congress interfered with the Sabbath, petitioners would soon be asking for taxpayer-funded ministers and houses of worship. Johnson’s two reports against the Sabbatarian campaign, which were in fact written by his friend, the Baptist minister Obadiah Brown, made him a champion of religious freedom in some circles.

The political firestorm over the Sabbath was just a prelude to what would be an embattled few decades for Beecher. Through the 1820s and 1830s he found himself engaged in a bitter theological controversy, attacking Unitarian liberals for their rejection of Calvinism and defending himself against charges of doctrinal irregularities made by conservative, “Old School” Presbyterians. In 1832 he took his battle to what was then considered “the West” and assumed the presidency of Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati. There he came face to face with what was his era’s most controversial issue: slavery. Until taking up his post at Lane, Beecher had been able to avoid the matter. But when the Lane trustees forbade discussion of slavery for fear of antagonizing the school’s Cincinnati neighbors, Beecher faced a serious crisis. Most of the more radical student body bolted to Oberlin College, which had been founded in 1833 and had become a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment. Beecher’s preference for a moderate, unified antislavery course foundered, as it would across the nation in the years leading to the Civil War.

By 1840 Beecher reentered the political fray. During the 1830s, Americans who found President Andrew Jackson and his policies disagreeable had formed the Whig Party. Beecher’s eldest daughter, the educator Catharine Beecher, had been a leading organizer of petitions against Jackson’s policy of Indian removal, the forced relocation of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States. In the presidential election of 1840, Lyman Beecher threw his support behind the Whig candidate, fellow Ohioan William Henry Harrison (fig. 5). Whigs played up the issue of Harrison’s piety, and Sabbatarians and temperance advocates flocked to his standard, regardless of his famous campaign image as a common man who inhabited a log cabin and drank hard cider. Unfortunately for the Whigs, Harrison’s sudden death a month after his inauguration dashed their hopes for an administration of godliness and morality.

In 1844 Beecher endorsed the Whig ticket of Henry Clay for president and Theodore Frelinghuysen for vice president (fig. 6). Frelinghuysen, former United States Senator from New Jersey and onetime president of the Sabbath Union, embodied Beecher’s ideal of “the Christian statesman,” but Beecher’s support soon became a liability for the Whigs. In a political move worthy of Karl Rove, the Democrats reprinted forty thousand copies of Beecher’s old anti-dueling sermon so as to embarrass Clay, who had been involved in a couple of duels in his younger days. The Whigs narrowly lost that election, in part because the growing Irish Catholic population in New York City, suspicious of the kind of Protestant moralizing represented by Beecher and Frelinghuysen, voted heavily Democratic.

What lessons can we take from this selective look at Lyman Beecher’s public career? For one thing, he was correct to conclude that the days of the New England founders, who had sought to make church and state mutually supporting, had passed. The United States Constitution is a secular document that prohibits religious tests for office and that outlaws direct state support of religious institutions. Beecher recognized that only to the extent that the United States was populated by those who adhered to traditional Christianity—what he termed “the faith once delivered to the saints” in his 1823 sermon, quoting Jude 3—would it be a Christian nation.

At the same time, the “separation of church and state” does not mean that voters informed by religious values would remain silent. As Beecher’s generation spoke out against Sabbath breaking, intemperance, Indian removal, and slavery, so people of faith today will continue to champion so-called social issues in the political arena. But they should not expect to be popular as a result. Beecher’s experience exposed both the necessity of speaking out and the inevitability of the ensuing controversy. Moreover, professed Christians of different denominations may very well line up on opposite sides of issues. Congregationalists and Baptists, for example, tend to take different stands on numerous questions today no less than in Beecher’s time.

Beecher achieved his clearest successes when he operated independently of government. The evangelical organizations in which he played such a prominent role really did change the culture and help inaugurate the Victorian era. The same is true of the temperance movement. Yet Beecher also showed that the political parties are unavoidable. He desired Christians to remain above the partisan fray, but he also realized the necessity of eventually choosing to be involved with one or the other if one hoped to influence public policy. Then as now, elections have consequences. Harrison’s untimely death and the Whigs’ narrow defeat in 1844, for example, led to war with Mexico and the expansion of slavery. Beecher’s son, Henry Ward, would side with the new Republican Party in the 1850s as the only effective instrument for breaking the Slave Power’s grip over the United States.

Lyman Beecher’s efforts to scrutinize the morality of governmental policy and to mobilize voter support for his causes ultimately contributed to the robust, participatory democracy of antebellum America. He carried a Puritan tradition of prophetic preaching into the early republic and set ground rules for Christian involvement in politics that are still relevant. Contemporary American political culture, with its “values voters” and “faith forums,” is heir to his legacy.

Further Reading:

An invaluable source for understanding Beecher is Barbara M. Cross, ed., The Autobiography of Lyman Beecher, 2 vols. (Cambridge, Mass., 1961). Originally published in 1864, it is a collection of his and his children’s reminiscences and letters that were compiled during his retirement years after 1850. It also includes extracts from many of his most noteworthy sermons.

The best general biography of Beecher is Vincent Harding, A Certain Magnificence: Lyman Beecher and the Transformation of American Protestantism, 1775-1863 (Brooklyn, N.Y., 1991). There are perceptive chapters on Beecher’s evolving thinking about social reform in Robert H. Abzug, Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination (New York, 1994) and John G. West Jr., The Politics of Revelation and Reason: Religion and Civic Life in the New Nation (Lawrence, Kans., 1996). Two works that include Beecher as an important participant in debates over religion and politics are Richard J. Carwardine, Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (New Haven, Conn., 1993) and Richard R. John, “Taking Sabbatarianism Seriously: The Postal System, the Sabbath, and the Transformation of American Political Culture,” Journal of the Early Republic 10:4 (1990): 517-67. On the election of 1800 see Frank Lambert, “‘God—and a Religious President…[or] Jefferson and No God’: Campaigning for a Voter-Imposed Religious Test in 1800,” Journal of Church and State 39:4 (1997): 769-89. Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York, 2007) provides a magisterial survey of Beecher’s age.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Jonathan D. Sassi is associate professor of history at the College of Staten Island and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and author of A Republic of Righteousness: The Public Christianity of the Post-Revolutionary New England Clergy (New York, 2001).