Science and art come to the Oregon Trail

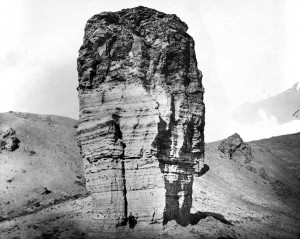

When the photographer William Henry Jackson posed fourteen men around a table in a field, propped a deer head on a keg for display, and allowed a dog to continue lying in the shade of a wagon, he was articulating complicated relationships among people, animals, and landscape—but he didn’t think much about such stuff. He thought only of the pose. Once he had everything placed, he entered the photo himself and stood as its fifteenth human subject at the right-hand end of the group. He turned his side to the camera, raised his left hand to his hip, looked slightly downward toward the center of the composition, and instructed an assistant to make, as he would have said, the view. The assistant, the third cook or a teamster, reached around to the front of the tripodded camera, removed the lens cap for many long seconds, and then replaced it over the lens. “Red Buttes,” Jackson wrote that night at the top of his diary page. It was a well-known landmark in Wyoming Territory, near present-day Casper, where the old emigrant road left the North Platte River and struck off toward the Sweetwater. Then he added “Layover—Views of camp and of men in a.m.” Even today, it may be the great landscape photographer’s best-known photograph. And it’s full of people.

The camera was new that summer of 1870. Jackson had telegraphed to New York City for it from Omaha, where he kept his studio, and it had arrived barely in time for him to join these men as their official photographer. Other field summers had taught him the importance of traveling light. By now, he had reduced the equipment that made his “views” to only about three hundred pounds. He could pack everything for a day’s work onto a mule rather than a far more cumbersome horse-drawn wagon.

Because the negatives from the new camera were so large (five by eight inches) and because Jackson understood so well what focus, light, and various lenses could do, his pictures had always captured an enormous amount of visual information. But only in the weeks of August 1870 was Jackson becoming a great composer of images. In a single summer, he became a mature artist. Innocent as he was—un-ironic, Romantic, enthusiastic—pictures like the one at Red Buttes show he also was beginning to engage the complexities of power.

Two cooks stand at the left-hand edge of the group, flanking a small camp stove with three black pots on it. From the stove rises a pipe with a right-angled elbow at the top, sending smoke behind the head of the right-hand cook. Next, six men stand along the rearmost plane of occupation, ending with Jackson on the right. But no two stand alike. Sanford Gifford, the painter, cocks a lanky shoulder upward and gazes toward us. Next, the geology draftsman Henry Elliott looks down toward the center of things; next to him, James Stevenson, second in command, leans forward slightly, hand outstretched toward his seated boss (of whom more shortly). Then a gap, through which we can see the grass stretch back to the base of the hills; then three more men—Schmidt, the naturalist; Carrington, the zoologist; and Bartlett, listed as “general assistant.” These men are followed by another gap through which we can make out some horses grazing; then the dashing Jackson—wearing his long hair tied back, wearing a string tie perhaps, with the near side of his hat brim flipped up; then the hind end of a mule in the background; and finally, down the right-hand edge of the photo, a slice of wagon in whose shade in the lower right-hand corner luxuriates a dog, who has just stretched snout and forelegs into the sun.

In front of the standing men, five more men sit at a wooden table. They appear at ease; there are dishes, a pot, and a pitcher on the table as though they had just finished breakfast, and one or two are holding cups. Left to right they are Turnbull, secretary of the expedition, leaning forward with a forearm on his thigh; Beaman, meteorologist, who often assisted Jackson in the field; and at the back end of the table, Ferdinand V. Hayden, MD, geologist and leader of the expedition. At the near corner, elbows on the table, looking off to the left sits entomologist and agriculturalist Cyrus Thomas in a black frock coat. Behind him and to his right sits Raphael, an interpreter the explorers had hired fifty miles earlier at Fort Fetterman. And further right, in front of Jackson, sits Ford, mineralogist, who may be stirring up batter in a dishpan. In front of Ford’s shins, the deer head is propped with its nose on the top of a smaller keg and the back of its skull against a taller one. The image is so sharp that it’s evident the antlers are still in velvet.

Hayden, the leader, sits hatless at the back of the table. The men’s postures are casual—most are wearing work clothes—yet the effect is formal. It’s not just a group portrait of the members of the 1870 United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. It’s a picture of power, of who’s in charge. Hayden’s face is at the exact center; diagonals drawn corner to corner would intersect close to his nose. Each of the several casual postures defers to his single presence. Sun blazing off his forehead, left shoulder just slightly back, he gazes out at us from well back in the group, dominating everything.

Hayden had an uncertain and difficult childhood that he seldom talked about as an adult. He was born in Connecticut and was more or less an orphan until the age of thirteen, when he landed safely on an aunt and uncle’s farm in Rochester, Ohio. A few years later he entered Oberlin College, then a hotbed of abolitionism, but appears to have chosen the natural sciences over politics. In 1851 he entered medical school in Cleveland. There he met John Strong Newberry, a recent graduate of the same medical school and a rising geologist and paleontologist. Through Newberry, Hayden came into contact with the geologist James Hall, of Albany, New York. When Hall needed an extra assistant for a western collecting expedition he was organizing in 1853, he gave Hayden the job.

Thus it was that twenty-four-year-old Hayden got his first look at western rocks from the deck of a steamboat belonging to the American Fur Company. The trip up the Missouri was slow for a brisk young man, but it allowed for day after day of gazing at the riverbanks and bluffs and a chance to talk over the meanings of the strata with Fielding Meek, whom Hall had deputized to lead the expedition. Meek was an invertebrate paleontologist of broad knowledge and curiosity, engaged then in using the fossils of ancient shellfish and other creatures to understand which rocks were older and which younger—part of the great, worldwide ordering task of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century geology. They disembarked at Fort Pierre in what is now South Dakota and headed southwest into the badlands along the White River. That bleached, gullied landscape is still one of the richest fossil localities in the world. But Indian disapproval and logistical difficulties forced Hayden and Meek to leave after just three weeks.

In that brief time Hayden learned valuable lessons. He learned chiefly that he loved geology; that no science would get done unless the details of finance, travel, and supply were attended to first; and that stable finance required stroking the patron.

In Hayden’s time, geology was a visual science. A geologist needed a good eye to follow a rock layer sometimes hundreds of miles, as it dipped and rose in and out of sight. He also needed to be able to imagine the curves turned or faults suffered before the layer had eroded away or disappeared underground. He had to know fossils, too, and their order in time, as the fossils provided vital clues about when, relative to other layers, a layer in question had folded, faulted, or washed away.

Hayden soon finished his medical degree and with its extra cachet and his own ambition advanced quickly in the natural sciences. Within a year or two he was collecting rocks and fossils for men at the highest reaches of American science, including Spencer Baird of the new Smithsonian Institution and Joseph Leidy of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Hayden generally worked alone in the field but continued to turn to Meek for advice about his finds. Together they published sixteen scientific papers, the most important of which contained the first-ever stratigraphic column of the rocks—a chart that named the layers and showed their relative order and thicknesses—on the upper Missouri. With Meek’s help, Hayden was becoming an important scientist.

After some geological work as a civilian with the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, Hayden’s scientific career was interrupted by the Civil War. He would serve as an officer, an army surgeon who started out amputating wounded limbs. Soon he moved up to running hospitals.

After the war Hayden accepted a professorship in geology and mineralogy at the University of Pennsylvania. But it paid little, and he kept collecting to supplement his income and satisfy his curiosity. In the spring of 1867, his friend Spencer Baird in Washington learned that Congress had approved a survey of the southeastern counties of the brand-new state of Nebraska. Hayden got the job, along with a similar one the following year along the new Union Pacific line to its temporary terminus at Fort Bridger in southwestern Wyoming Territory. Though these surveys were under the auspices of the General Land Office, the agency overseeing the sale of federal land, they were not square-mile-by-square-mile land surveys. They were on-the-ground inquiries into just what was out there; they were systematic, yet designed to cover lots of country, primarily to find where minerals might lie and where crops might grow best.

The grid of federal land surveys had been stepping westward from Ohio since shortly after the Revolutionary War, but for generations, farmers, prospectors, and cattlemen had kept ahead of it, claiming squatters’ rights—”preemption rights” they were called as they moved from custom into law—to the choicest lands. To control the resulting legal and financial mess, Congress had finally decided to finance organized teams of explorers and surveyors as a first step toward a more controlled exploitation of the resources of the West.

Hayden’s survey was one of four financed by 1870, and it is probably best known for its exploration of the Yellowstone country. Competition for funds would grow steadily through the 1870s, until consolidation was in order. In the final maneuvering, Hayden would lose out. Partly because of his own weaknesses, partly because his competitors outlived him and controlled the accounts that were written, he has come down in history as a failure. In 1879, another of the four survey chiefs, Clarence King, was named the first director of the United States Geological Survey. He was soon succeeded by the most famous of all these explorers, John Wesley Powell.

Jackson, the photographer, had grown up in upstate New York and Vermont, but his family had moved often, following Jackson’s father to rural Georgia and elsewhere. As a child he had shown skill with a pencil, and his mother bought him drawing books. At fifteen he put away higher artistic aspirations and went to work in a photographer’s studio in Rutland, Vermont, coloring and retouching photographs—painstaking and repetitive work.

During the Civil War, he spent a year as a soldier and filled idle hours sketching landscapes and encampments, before returning to Vermont. Then in 1866 a sweetheart jilted him, and he lit out for the western territories.

Jackson and two friends picked up jobs in St. Louis with an ox train of freight wagons, which took them to Salt Lake City. There—broke, his clothes in rags, and his boots worn through—he hit bottom, wrote home for money, and lived for a month with a charitable Mormon family. He eventually bought passage on a wagon train bound for Los Angeles. By the spring of 1867, he was headed east again, this time working with a crew herding hundreds of wild horses back over the same route he had so recently traveled.

In Omaha he landed a job in a photography studio, at wages as good as he had ever made back East. Working steadily, with a room of his own to return to, Jackson finally seems to have found a little stability in his life.

While learning how to make a living in the West, Jackson gave himself a visual education. Sketches like the one he made of Chimney Rock left no little human figures in its foreground, no houses, no soldiers’ huts, villages, streams, or farmsteads—no sign at all of human habitation or movement. Everything seemed blasted by a new, blank enormity. The world was too big to be beautiful; whether it was picturesque or sublime would have to remain unanswered for a while, as the budding artist grappled with rocks, distance, and sky.

Jackson worked in the photography studio for most of a year before his brothers joined him in 1868. With financial help from their father, the brothers bought the studio where Jackson had been working. It proved a smart investment. Omaha was booming.

The town was the eastern terminus of the growing Union Pacific, and it thronged with workers. They wanted pictures of themselves to send home. And tourists, too, wanted pictures—not of themselves but of the western landscape they had come to see. Mountain views they wanted, scenery, splendor, and if in stereopticon slides, even better. They also wanted pictures of Indians. Jackson began making regular visits to the Otoes, Omahas, and Pawnees who lived on reservations near Omaha. To a growing and lucrative selection of negatives he added views of the large Pawnee villages, of mud houses, and of individuals posed alone in slanting sunlight.

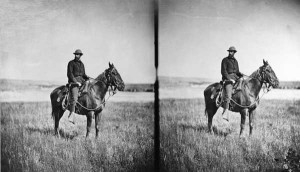

In 1869, Jackson and an assistant spent the summer taking photographs along the route of the Union Pacific. It was the year the transcontinental railroad was completed.

The summer’s work proved immensely profitable for Jackson. As he traveled along the Union Pacific line, he found a ready market for his images of the newly crossed West. In Cheyenne he and his assistant cleared sixty dollars in three days—not bad in light of the twenty-five dollars per month Jackson had lived on during his best-paid days as a retoucher. Late in the summer, still traveling, Jackson got word from his brother Ed in Omaha that a New York photographic publisher wanted ten thousand prints of pictures from the Union Pacific line. The railroad had split the West like a ripe fruit, and the terrain seemed to be spilling its lucre into Jackson’s pocket.

Jackson first saw Hayden the same summer, while delivering a batch of prints at Madame Cleveland’s, a Cheyenne brothel. Jackson watched Hayden and some soldier friends walk in. The scientist, Jackson wrote in his diary, “acted like a cat in a strange garret,” but if the two men spoke, Jackson did not record the conversation. (This encounter is interesting in light of Hayden’s long decline through the 1880s to his death in 1887 when he was just fifty-eight. He died of locomotor ataxia, a paralysis resulting from syphilis.)

Their first real meeting came a year later, when Hayden walked into Jackson’s studio in Omaha. By then, the young photographer already had a national reputation for his images of the West. But what most drew Hayden to Jackson’s work was not its rendering of the western landscape and its people, but Jackson’s unique respect for rocks.

There they were, in picture after picture, massively layered, detailed, and identifiable, sometimes accompanied by—but never subordinate to—people, trees, or railroad tracks. Hayden offered to cover Jackson’s expenses for the summer if he agreed to serve as official photographer for the 1870 survey. Jackson would be expected to make prints for the survey for free, but he would be allowed to keep the negatives. His new wife, Mollie Greer Jackson, could run the business expertly while he was gone—she was much better at it than his brothers. Jackson accepted. On the first of August, he caught up with the expedition at Camp Carlin, an Army supply depot outside Cheyenne.

Hayden writes in his report for the summer of 1870 that it was the rocks that drew him north from Cheyenne. But he almost certainly wanted to make historical connections as well. He wanted to hunt up the locations of the past—places with nostalgic names that congressmen would recognize. On leaving the railroad, the survey traveled north past the foothills of the Laramie Range, then linked up with the old emigrant road—the Oregon-California Trail—and turned west up the North Platte valley. They traveled with four heavy wagons and two light ambulances. The teamsters and cooks kept these near the roads, while the artists and scientists ranged and roamed alone or in small parties on horseback.

Jackson kept his bulkier gear in one of the ambulances and had a lighter outfit that he could pack for a day’s work on the back of Hypo, his fat, cropped-eared mule, named for hyposulfite of soda, a darkroom chemical.

The country along the emigrant road was recovering from the devastation caused by decades of traveling emigrants and, especially, their voracious livestock. The latter had devastated the countryside, devouring the plants that had sustained much of the regions’ game. But by the time of his visit, Jackson could report plenty of antelope in his diary. The morning after they had left Red Buttes, Jackson, Gifford the painter, and Beaman the meteorologist started out from their camp at a place called Willow Springs. “Distant sight of lone Buffalo,” Jackson recorded that night. “Cautious approach—commencement of hostilities—the Chase—Excitement!—Much firing but not effective.” They quit, for a time. Later they spotted a herd of nine—in a later autobiography Jackson numbers it at “thirty or forty”—but these buffalo, too, got wind of them and galloped off through the thick sagebrush. Still later, Jackson, Gifford, and probably Beaman made a long detour downwind of three more buffalo and finally, with help from others in the party, managed to kill all three. Though both Hayden and Jackson had passed this way before, neither noted any improvement in the look of the country. Still, thirteen buffalo in the twenty miles between Willow Springs and Horse Creek was a great many more than people were seeing five and ten years earlier. With the nation’s east-west artery now moved elsewhere and the Indians pushed north of the North Platte, the country was largely empty of humans other than themselves. It was almost as rich in game as it had been in the early 1840s, before serious emigration began.

Fifty miles southwest of Red Buttes, the party camped two nights at Independence Rock. Hayden was stirred by the geology and understood its main parameters perfectly well—that Tertiary sediments there lap up against granite outcrops that are far older—”jut close up against their base” was how he put it. He understood correctly that Independence Rock and the granite ridges around it are made from the same material. He also saw that its dome shows erosion by exfoliation, or a peeling off of the outside layers as it continues to expand from within. In his excitement, he climbed the granite ridges just south of Independence Rock, and from there he could look and look to his heart’s content.

“From the summit as far as the eye could reach in every direction granite ranges could be seen, of varying lengths, from one hundred to fifteen hundred feet above the surrounding plains . . . In some of the broad intervals are the most beautiful terraces or benches, sloping gently down from the base of the mountains to the valley. Not a sign of water could be seen in any of these mountains at the present time. A few cottonwoods and groups of quaking asps, in some of the ravines on the sides, gave evidence that water issues from them at certain seasons of the year. A few stunted pines struggled for existence among the crevices, and some rare shrubs and ferns were all the vegetable life observed.”

He continued, “It seems as though the Sweetwater flowed through this valley for fifty miles or more with scarcely a tributary to add to its volume.” That observation is not true, though it appears that way from the top of those rocks.

The first day at the rock, Jackson made some pictures, but it was cold and windy. The following day was clear and still. Jackson, Elliott the draftsman, and perhaps Gifford led Hypo up the rock to try again. He faced his camera downriver, east toward the North Platte and a pair of peaks beyond it. In the photo that resulted, Elliott lounges with his sketchbook in the right foreground, but the rocks are quickly sloping away, and in the right middle ground, just beyond the river, the viewer’s eye quickly finds five tents and four wagons. Two horses graze to the left of the tents, near the river, and the broad channel of the river itself flows briefly up the middle of the picture before bending off to the left. The big rocks that Hayden climbed for a better view of everything slope into the picture from the right.

Despite foreground, middle ground, background, and sky, this is no conventional composition. Granite takes up a full third of the picture. The rock appears in such close detail one knows without thinking that the rock is rough to the touch and warm from the sun, with a breeze cutting around its edges. Still the viewer’s eye rests finally not on the granite but, again, on the receding river at the middle of the picture—out there in space and emptiness, flowing away, and leaving behind a stillness, from which it is very difficult to look away.

That same day they left the rock, packed up, and headed toward Devil’s Gate, the dramatic, 360-foot-deep granite gunsight through which the Sweetwater makes an odd and sudden detour. They did not camp, but Jackson, Gifford, and Elliott climbed to the top with the camera and looked out again over a receding sweep of country—upstream now, to the west. The result is another stunning image. More sky this time. Again in the foreground, diagonals of granite, though now the immediate rocks make a shallow vee. In the middle distance on a flat by the river, is just a single wagon, one of the ambulances, and a tiny man is standing halfway between wagon and riverbank. Gifford and Elliott crouch on the right-hand side of the vee, looking away and outward. Again, the eye follows up the middle of the image, over the wagon, to the river as it meanders, loops, and finally disappears toward the hazy mountains and the sky.

In a single image, Jackson hands us depth, space, hints of future human occupation, and an appearance of documentary verisimilitude that, in fact, is packed with emotion. Here the geological forms sweep the eye down and then, with a big whoosh, out—to infinity. With these qualities he also hands us, right at the center, the same qualities that were in the center of the photo at Red Buttes: Hayden’s power and Hayden’s ambiguity.

There are not yet corrals by the river, where later the vast Sun Ranch will headquarter its empire. There is no sign of the trading cabins where the French-Shoshone families prospered for a few years in the 1850s, nor any abandoned handcarts left by the starving, freezing Mormons who stopped here for a week in 1856. There is very little brush by the river compared to now, and the space between the two nearest bends looks sandy, still perhaps badly damaged by decades of emigrant cattle. It is hard to say, however. Mostly it looks appealingly empty. But not quite. There are people here in the middle of nowhere, says the picture. Who are they? What will they do? What stories will they tell?

Further Reading (and Viewing):

See all of Jackson’s photographs from his years with the Hayden Survey at the U.S. Geological Survey’s online photo archive. Go to “continue,” then use the “free form” search and enter “jwh0” in the first window—all Jackson’s photos are archived with numbers starting with that code—and use the other windows for dates, places, or any other qualifying search terms. This is the place, too, to enter names of other great survey photographers of western landscapes; try Hillers, O’Sullivan, or Russell. These photos are all part of the public domain and available free for downloading and publication.

Jackson’s diaries from his first trip west, in 1866, are included in The Diaries of William Henry Jackson, Frontier Photographer, edited by Leroy and Ann Hafen (Glendale, Calif., 1959). The two autobiographies Jackson wrote late in his life, The Pioneer Photographer (New York, 1929) and Time Exposure (New York, 1940), are less reliable. Jackson, who needed a mule-load of stuff to take a picture in 1870, lived to be ninety and to shoot color film on a 35-millimeter Leica camera. His diaries from the summer of 1870, quoted here, are still unpublished and are in the collection of the Colorado Historical Society in Denver. My discussion of Jackson’s life and aesthetics relies heavily on Peter B. Hales’ excellent William Henry Jackson and the Transformation of the American Landscape (Philadelphia, 1988).

Hayden was a good descriptive writer, and his reports are still useful for the insights they allow into American boosterism, science, and aesthetics after the Civil War. They were published by the Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C., annually in the 1870s and may be found in good university and public libraries. His account of the 1870 expedition is in the Preliminary report of the United States Geological Survey of Wyoming and portions of contiguous territories, 1871.

The best overview of the post-war government surveys in the West may still be William Bartlett’s Great Surveys of the American West (Norman, Okla., 1962). See also William Goetzmann’s Exploration and Empire: The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the West (New York, 1966). But anyone seriously interested in Hayden should balance the fading failure of a man portrayed in Donald Worster’s River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell (New York, 2002) with James Cassidy’s more sympathetic portrayal in Ferdinand V. Hayden: Entrepreneur of Science (Lincoln, Neb., 2000).

This article originally appeared in issue 6.2 (January, 2006).

Tom Rea is a freelance writer in Casper, Wyoming. This piece and an article on John C. Frémont in the July 2004 Common-place are excerpted from his new book on the country around Independence Rock and Devil’s Gate in Wyoming. The Middle of Nowhere: Who Owns the Story of the West? is due in fall 2006 from the University of Oklahoma Press.