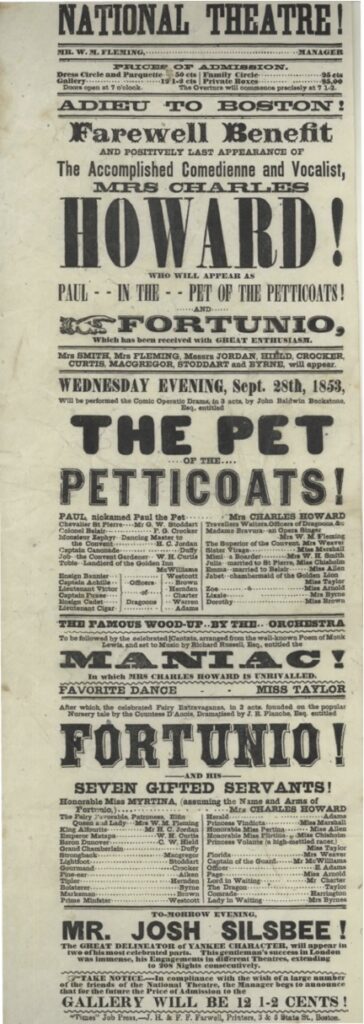

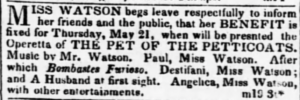

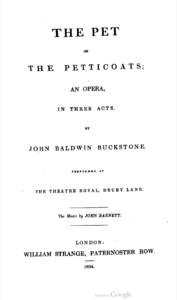

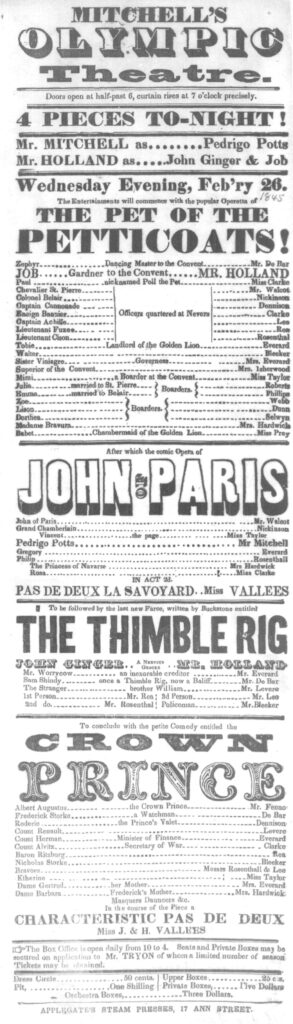

In March 1838, theatergoers in St. Louis were coaxed out into the bitter March cold with the promise of a new comedy, Pet of the Petticoats. It was set in a French convent and starred local favorite Eliza Petrie in a breeches role as Paul. He is the “pet” of the convent boarders, who are attempting to reunite with soldier husbands. Paul helps to liberate the boarders and unite the lovers, meanwhile engaging in his own adventure and making “love a la militaire” to a touring opera star. Petrie’s performance as Paul, which played on the comedy and sexual allure of the actress-as-boy role, made for an “immense” night by the standards of the dismal season.

It also generated some negative publicity in the local paper from a habitué of the theater. This critic found Pet “abominably gross in language [and] implying a slur upon one of the institutions of a numerous and highly respectable sect of Christians.” St. Louis had a long-established and thriving Catholic community, a recently completed cathedral, as well as a small convent school. Another theatergoer wrote in defending the comedy. He noted its popularity with women theatergoers, a sign that it did not offend “the female ear.” And to “put at rest the question of its moral tendency,” he clarified that the “plot of the ‘Pet’ is not derived from the story of Maria Monk,” the bestselling 1836 exposé of the sexual crimes committed in a Montreal convent. This was the moral offense and insult to Catholicism, rather than a light satire on convent life. Pet had nothing to do with the prurient anti-Catholic literature of dubious authenticity flying off American bookshelves. Or did it?