Hendrick Aupaumut has had many collaborators, but it wouldn’t be entirely correct to say that he has worked with many of them. Aupaumut, an eighteenth-century sachem of the Mohican tribal nation, produced many English-language texts that exist in published forms today because someone else put them into print. (This is no doubt in addition to the Mohican-language texts that this bilingual tribal leader also produced.) The first and most often read English-language example is Aupaumut’s “A Short narration of my last Journey to the western Contry,” a handwritten journal that he composed when selected by President George Washington in 1792 to negotiate with what Lisa Brooks (Abenaki) calls the “United Indian Nations”—a confederation of indigenous tribal nations in the Ohio Valley (including the Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware) that were challenging the new United States. Although Aupaumut’s negotiations did not ultimately result in peace between the United States and the United Indian Nations, the journal that he supplied to Washington after his journey is quite significant for many reasons, not the least of which is that it provides an indigenous perspective on this important historical moment. Years after it had been read and copied by the Washington administration, the journal somehow ended up in the hands of Philadelphia antiquarian Benjamin Coates. It was then printed—without Aupaumut’s permission, input, or even knowledge—in the 1827 edition of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Memoirs.

But just as interesting and important is the short “History” Aupaumut wrote of his Muh he-con-nuk Nation. In what follows, I compare how Electa Jones (a historian working in western Massachusetts in the middle of the nineteenth century) and Kristina Heath (a contemporary Mohican/Menominee writer) have engaged with Aupaumut’s “History.” I first look at how Jones included Aupaumut’s “History” in her Stockbridge, Past and Present; or, Records of an Old Mission Station (1854) and then at how Heath uses Aupaumut’s “History” as the basis for her Mama’s Little One (1996). Indian texts have been mobilized for many purposes over the years, and there’s no such thing as a neutral reproduction of Aupaumut’s text. Briefly tracing how this particular text has been deployed shows us how Jones places Indianness in the past of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and how Heath uses it for the continuance of Mohican culture. In other words, Jones’s orientation to Mohican culture is that it is a historical artifact, but Heath calls attention to and indeed enacts Mohican culture in the present and into the future. As I hope to make clear, Heath turns Aupaumut’s “History” away from the colonial context of Jones’s Stockbridge, Past and Present and places it into a framework of ongoing indigenous history and tradition.

We believe that Aupaumut wrote his “History” sometime in the early 1790s. Because it is written in English, we suspect that the “History” was intended mainly for a white audience. (It most likely existed alongside an oral Mohican-language tradition told to and passed down among the Mohican people.) Even so, the only extant versions are those that appear within other texts from a slightly later period. Scholars have yet to locate an “original”; all we have is the way that “History” has been used in (and mediated by) other writers’ work. One version appeared in the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1804), another in the First Annual Report of the American Society for Promoting the Civilization and General Improvement of the Indian Tribes of the United States (1824), well before Jones included Aupaumut’s “History” in her Stockbridge, Past and Present. Scholars tend to look to Jones’s text when reading Aupaumut’s “History” because it is, as Hilary Wyss points out, the most complete of the three extant, fragmentary versions. When we look at Aupaumut’s “History” included within Jones’s Stockbridge, Past and Present, we might be tempted to ask: how faithful is Jones’s copy to Aupaumut’s missing “original”? How “authentic” is Jones’s text, or the intertwined Jones-Aupaumut text?

Questions of authenticity can often be of central concern for those approaching Native texts, but aren’t there other interesting questions we can ask? Or, perhaps, is there another set of questions we could pose that get at entirely different—but just as pressing—concerns? For example, what role does Aupaumut’s text play in Jones’s text? What effect did its inclusion have? What choices did Jones make in terms of how to contextualize Aupaumut’s text? How does Jones’s framework affect how we read Aupaumut’s text? Put simply: How did Jones do things with Indian texts, and what can we learn from asking such a question?

Jones includes Aupaumut’s “History” as part of a chapter on “Indian History” within Stockbridge, Past and Present, as an interesting aspect of the town’s background. In the chapter, she chronicles the group of Mohican Nation Indians who lived there during the eighteenth century. While one might expect Jones to treat Aupaumut’s “History” as the “pre-history” of Stockbridge “proper”—as something that comes to an end with permanent white settlement—it might be more fitting to say that Jones includes Aupaumut’s text and the subsequent chapters she writes on the Stockbridge Indians as one of the more distinctive features of Stockbridge’s past. On the one hand Jones’s text partakes of nostalgia of the vanishing Indian: “And the Red Man too; —oh, how little do we think of him! How little do we know of him! How seldom, how very seldom, does the public prayer ascend for the children of those who once lived in these valleys, hunted in these groves, angled in these streams, worshiped where we bow, and were the STOCKBRIDGE CHURCH!” (10). But Jones also draws attention to their continued existence elsewhere: “They have ‘melted away’ indeed, but not like many of their race. They still have a national existence, still hold the religion which they learned upon this spot, and still love, with true Indian fervor, the homes and the graves of their fathers here” (10). Later in Stockbridge, Jones traces the Mohican paths through Ohio to Wisconsin (where the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians resides today). She suggests, in other words, that relocation is not the same as irrelevance; the story of the Mohicans is still important to the story of Stockbridge, even though they may have left.

Jones includes Aupaumut’s “History” as part of a chapter on “Indian History” within Stockbridge, Past and Present, as an interesting aspect of the town’s background. In the chapter, she chronicles the group of Mohican Nation Indians who lived there during the eighteenth century. While one might expect Jones to treat Aupaumut’s “History” as the “pre-history” of Stockbridge “proper”—as something that comes to an end with permanent white settlement—it might be more fitting to say that Jones includes Aupaumut’s text and the subsequent chapters she writes on the Stockbridge Indians as one of the more distinctive features of Stockbridge’s past. On the one hand Jones’s text partakes of nostalgia of the vanishing Indian: “And the Red Man too; —oh, how little do we think of him! How little do we know of him! How seldom, how very seldom, does the public prayer ascend for the children of those who once lived in these valleys, hunted in these groves, angled in these streams, worshiped where we bow, and were the STOCKBRIDGE CHURCH!” (10). But Jones also draws attention to their continued existence elsewhere: “They have ‘melted away’ indeed, but not like many of their race. They still have a national existence, still hold the religion which they learned upon this spot, and still love, with true Indian fervor, the homes and the graves of their fathers here” (10). Later in Stockbridge, Jones traces the Mohican paths through Ohio to Wisconsin (where the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians resides today). She suggests, in other words, that relocation is not the same as irrelevance; the story of the Mohicans is still important to the story of Stockbridge, even though they may have left.

Most importantly for my purposes here, Aupaumut relates a practice that was “considered as communicated to them by Good Spirit,” where “The Head of each family—man or woman—would began with all tenderness as soon as daylight, to waken up their children and teach them, as follows: —” (18). Then, in a quote within a quote (Jones quoting Aupaumut quoting the Mohican “Head of each family”), the text details the lessons imparted by Mohican parents to their children. The lessons include instructions on assisting the elderly, telling the truth, being industrious, and obeying the counsel of the sachems and chiefs. Unlike the rest of the “History,” this section is structured by the rhythm of repetition. The direct address to “My Children” opens each lesson and signals both acoustically and typographically when each new message commences. And although not on the printed page, the lessons also repeat in lived time—as Mohican ancestors impart the lessons to their children, to their children’s children, to the eighteenth-century present people of the Mohican nation, and to the future children of the lasting Mohican nation.

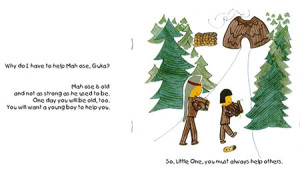

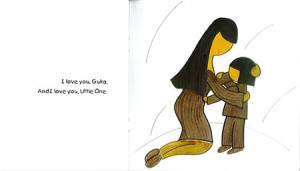

Drawing upon this idea of repeating lessons into the future is how writer Kristina Heath (Mohican/Menominee) decides to do things with Indian texts in her own book, Mama’s Little One. Heath grew up on the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians’ reservation in Wisconsin, and she encountered Aupaumut’s “History” in an undergraduate course on Mohican history at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. In 1996, she wrote, illustrated, and published Mama’s Little One with Muh-he-con-neew Press. Adapted from Aupaumut’s “History,” the text describes a Mohican mother waking her young son in the morning and depicts the dialogue between the mother and son as she teaches him the important lessons laid out in Aupaumut’s account. Here, Heath beautifully depicts the female “Head of family” teaching her son, as Aupaumut says, “with all tenderness.”

Heath’s book is a fantastic example of a Native writer performing what Scott Richard Lyons (Ojibwe/Mdewakanton Dakota) calls “rhetorical sovereignty,” the right of indigenous peoples to represent themselves as they see fit. Heath neither assumes that Aupaumut’s text-within-Jones’s-text has been either compromised or not compromised by its inclusion in a white text. Rather, Heath turns to Aupaumut’s text-within-Jones’s-text as an Indian text that reflects a complicated layering of Indian-white interaction—a text that invites questions and discussion rather than conclusions—a text that insists that something be done with it. And what Heath decides to do is produce Mama’s Little One, a book that performs rhetorical sovereignty by using the earlier text as a particular kind of historical document and re-using it in a specifically tribally centered way—not only as a record of the past (as Jones does in Stockbridge) but also as a message to Mohicans now and to Mohicans of the future. Heath sets Mama’s Little One at the turn of the nineteenth century—when Mohicans gathered wood to heat their wigwams and hunted food to feed their families—but it has pointed contemporary resonance. The loving dialogue between mother and son (re)performs both the tradition laid out in Aupaumut’s “History” and enables today’s Mohican parents to do the same for their children, for their children’s children, and so on.

Indeed, the narrative structure of Mama’s Little One posits a Mohican past, a Mohican present, and a Mohican continuance into the future. There are no vanishing Indians here. Heath incorporates Mohican words such as “Mah ose” (grandfather), “Noh” (father), and “Guka” (mother), and she provides a glossary for her readers. This anticipates readers—both Mohican and non-Mohican—who don’t know the Mohican language. As such, it has much in common with other indigenous language revitalization efforts, such as those of Stephanie Fielding (Mohegan), Jessie Little Doe Baird (Wampanoag), and those supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and National Science Foundation’s Documenting Endangered Languages grant programs. Further, Heath’s book, along with other Native-authored children’s literature, features prominently in educational and enrichment programming, such as children’s literacy events and reading times held at the Arvid E. Miller Library and Museum at the Mohican reservation or at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, where children’s librarian Gabrielle Keys used Mama’s Little One in her programming. Indeed, Heath makes a different choice than Jones with regard to how to do things with Indian texts. For Heath, Indian texts are neither fixed nor timeless but rather part of a vibrant, responsive, and utterly contemporary cultural practice, and her approach enables others to continue using Indian texts in this way. In doing so, she joins other contemporary indigenous writers such as Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel, tribal historian of the Mohegan (a different indigenous nation), who use tribal history and traditions in their contemporary work, both fiction and historiography. Tantaquidgeon Zobel’s 1995 tribal history, The Lasting of the Mohegans, provides a useful rhetorical cue: rather than conceptualize Aupaumut’s “History” as simply history, Heath uses Aupaumut’s text to fashion what we might call a “Lasting of the Mohicans” into the future.

Further Action:

One might ask, in addition to our teaching and research, what things should we scholars today do with Indian texts? And how? We perhaps could simply support the writing and reading of these books. First, we can support the tribal institutions that make the production of texts such as Heath’s Mama’s Little One possible. The Arvid E. Miller Library and Museum is the cultural center charged with storing the archives of the Stockbridge-Munsee people, with providing the Stockbridge-Munsee members access to their history, and with keeping that history alive. The Miller Library and Museum, under the direction of manager Nathalee Kristiansen, also is undertaking a new building fund. A new and much-needed facility would allow the library more storage, more displays, and more programming based upon and geared for the Mohican people, thus preserving tribal histories and supporting vibrant cultural projects. If one thing you wanted to know how to do with Indian texts is how to support the building of a tribally centered place to produce them and to keep them, you should visit the Library and Museum Web page of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians. Second, we can support the writing and reading of these books by buying our own copies to read. Certainly one could order one of the few remaining copies of Mama’s Little One owned by large online retailers, but if one thing you wanted to know how to do with Indian texts (here, Mama’s Little One) is how to buy them directly and more economically, one should contact Leah Miller, elder historian of the Mohican Nation.

Further Reading:

Aupaumut’s “History” is extant in Electa Jones, Stockbridge, Past and Present: Or, Records of an Old Mission Station (Springfield, Mass., 1854); Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, first ser., vol. 9 (1804); and First Annual Report of the American Society for Promoting the Civilization and General Improvement of the Indian Tribes of the United States (New Haven, 1824). See also Kristina Heath, Mama’s Little One (Gresham, Wis., 1996). For more on how Hendrick Aupaumut worked for the future of the Mohican Nation, see Dorothy Davids, A Brief History of the Mohican Nation, Stockbridge-Munsee Band (Bowler, Wis., 2004); Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (Minneapolis, Minn., 2008); Hilary Wyss, Writing Indians: Literacy, Christianity, and Native Community in Early America (Amherst, Mass., 2000); Rachel Wheeler, To Live Upon Hope: Mohicans and Missionaries in the Eighteenth-Century Northeast (Ithaca, 2008); Sandra Gustafson, Eloquence is Power: Oratory and Performance in Early America (Chapel Hill, 2000), and “Historical Introduction to Hendrick Aupaumut’s Short Narration” and “Hendrick Aupaumut and the Cultural Middle Ground,” in Early Native Literacies in New England: A Documentary and Critical Anthology, eds. Kristina Bross and Hilary Wyss (Amherst, Mass., 2008); David Silverman, Red Brethren: The Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians and the Problem of Race in Early America (Ithaca, 2010); Alan Taylor, “Captain Hendrick Aupaumut: The Dilemmas of an Intercultural Broker,”Ethnohistory 43.3 (1996); and Katy Chiles, Transformable Race: Surprising Metamorphoses in the Literature of Early America (New York, 2014) and “Tribal Sovereignty, Native American Literature, and the Complex Legacy of Hendrick Aupaumut,” Tennessee Studies in Literature (Fall 2015). For more on the Mohegan tribal nation’s history, see Mohegan tribal historian Melissa Jayne (Fawcett) Tantaquidgeon Zobel, The Lasting of the Mohegans: Part I, The Story of the Wolf People (Uncasville, Conn., 1995). For more on how James Fenimore Cooper confused the Mohegan tribe with the Mohican tribe and was absolutely wrong about their extinction, see Drew Lopenzina, Red Ink: Native Americans Picking Up the Pen in the Colonial Period (Albany, 2012). For more on rhetorical sovereignty, see Scott Richard Lyons, “Rhetorical Sovereignty: What Do American Indians Want from Writing?”, CCC 51:3 (2000).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Kristina Heath, Leah Miller, Nathalee Kristiansen, Jessica Christensen, Paul Erickson, Drew Lopenzina, and Kelly Wisecup.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.2 (Winter, 2015).

Katy Chiles is associate professor of English at the University of Tennessee. Her book, Transformable Race: Surprising Metamorphoses in the Literature of Early America, was published in 2014. She is currently working on a book project about race, collaboration, and antebellum American literature.