In the fall of 1885, editor John McElroy was looking for something light to fill a few columns in his newspaper. The National Tribune was the leading veterans’ periodical, and its readers used the paper to follow national politics, pension affairs, and the latest advertisements for prosthetic limbs. On October 1, the Tribune featured on its sixth page a fictional story about a naïve Civil War enlistee named Si Klegg. It was a vacuous piece about a young farm boy leaving home to join the army and featured simple wood-engraved illustrations by George Yost Coffin, one of the Tribune‘s staff artists. This was an inauspicious start for the soldier who would become the best-loved fictional veteran of the Civil War. Before the serial abruptly vanished in May of the following year, the story of Si and his ironically named comrade “Shorty” had become one of theTribune‘s most popular features. Two years later, in 1887, Si and Shorty reappeared, this time in book form, under the authorship of Wilbur Hinman. Corporal Si Klegg and His “Pard” took Si and Shorty from their enlistment in Indiana through the war years and, for one of them, home again. George Coffin was again the illustrator of the work, but this time his sketches—some two hundred in number—were more precise and refined. Hinman’s book sold well, and soon became a favorite among both veteran and civilian audiences (fig. 1).

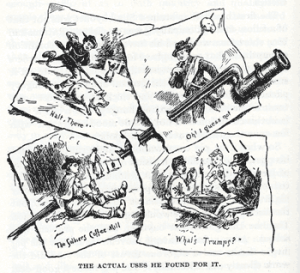

Like every man who enlisted, Si and Shorty endure the often-humorous transition from civilian to soldier. The two men learn to digest army rations, exterminate lice, perform all manner of manual labor, and sleep in miserable conditions. The essential violence of war is tangential to Hinman’s story. Shorty is killed in the final battle of the book. Soon after Shorty’s death, Si returns home to marry his childhood sweetheart and struggles in vain to receive his pension. Hinman does not linger on these events, a choice that reflected most veterans’ preference for books which overlooked the war’s gruesome brutality and its anticlimactic aftermath (fig. 2).

Wilbur Hinman had served with the Sixty-Fifth Ohio Infantry, part of the Sherman Brigade, and finished the Civil War as a Lieutenant Colonel. When his book first appeared, memoirs and histories of the war were at the height of their popularity. But Si Klegg was something different. It dealt not with generals and grand campaigns, or even the exploits of a single regiment. Instead, Hinman’s book was about the dirty, miserable, and joyful minutiae of soldier life in the Union army. The non-violent use of the bayonet as a candlestick or roasting skewer was far more fascinating to Hinman than the movement of divisions and brigades (fig. 3). Instead of quantifying the millions of pounds of flour and pork issued to the armies, he reveled in describing the personal experience of eating hardtack, “swine’s flesh,” and “desecrated vegetables.” Si’s first taste of military food prompts him “to realize what it was to suffer for his country.”

Si and Shorty know little and care less about the grand causes of the war. Instead, they apply their mental powers to more immediate applications, like the destruction of body lice, or pediculus vestimenti. “One of the great problems of the war was how to get rid of the pediculus,” Hinman tells us. “It was decidedly a practical question, and personally interested the soldiers far more than those of state sovereignty, confiscation, and the negro, which agitate the minds of the statesmen. Probably the intellects of most of the soldiers were exercised far more in planning successful campaigns against the pediculus than in thinking about those which were directed against Lee and Jackson and Bragg and Joe Johnston.” It was this combination of pragmatism, comedy, and wit which endeared Si Klegg to veterans and enthralled readers with no military background. Hinman withheld few things about the miserable details of soldier life, although his scruples prevented him from describing the state of undergarments in the later war, “lest I shock eyes and ears polite.”

The book also relied upon extensive dialogue, something often absent in Civil War works. Hinman’s characters conversed in a vernacular language intended to reflect the rural, laboring, Midwestern origins of Si and Shorty. When Si is sentenced to carry a knapsack full of bricks as punishment for a minor offense, his friend comforts him: “‘Tain’t nothin’ Si,” said Shorty, “lots on ’em has ter do it. Mebbe ye’ll be a bit tired ‘fore ye git done, but ‘twon’t hurt ye any.”

But Wilbur Hinman was speaking the language of the veterans in more ways than one. Accuracy and authenticity were central to his narrative, but Hinman did not allow these concerns to pollute Si Klegg with impersonal historical discussions. Unlike many veteran-writers, he felt no need to dissect every event of the war. Instead, this was a story about the experience as soldiers remembered it—a series of intimate events often disconnected from the war itself. As we shall see, this sort of memory was not happenstance, but rather the result of intentional decisions on the part of war-weary veterans.

Si Klegg enjoyed considerable success, going through twelve editions by the end of the century. The second printing in 1890 quickly sold 26,000 copies. Publishers distributed the book chiefly by subscription, for between $1.50 and $6.00 depending on binding quality, which ranged from cheap pasteboard to morocco leather with gilt embossing. Publishers provided selling agents, attracted by newspaper advertisements, with “dummy” copies which showcased the binding and best illustrations to make Si Klegg even more appealing to potential buyers. The characters were so popular with readers that Hinman’s former editor at the National Tribune, John McElroy, published his own series of Si Klegg stories.

After the success of Si Klegg, Wilbur Hinman published two other books. Camp and Field, Sketches of Army Life (1892) is a sparsely illustrated compilation of stories written by dozens of veterans and edited by Hinman. Their stories relate the humorous, dramatic, and martial events of the war “in the nature of a ‘campfire,’ around which the boys who conquered the great rebellion recount their adventures in Camp and Field.” The Story of the Sherman Brigade (1897), on the other hand, was Hinman’s attempt to appeal to readers who wanted a nonfictional account of their part in the Civil War.

The Sherman Brigade may have been a factual history, but it has innumerable connections to Si Klegg. With two successful books behind him, Hinman was the natural choice to write the history of his unit. And yet, as he had in Si Klegg, Hinman avoided any pretensions in his new composition. “Year after year at our Brigade reunions, with unfailing regularity, the boys continued to fire volleys of resolutions and speeches at me, whom, for some reason, they had drafted to do the work, and at last I have done it,” Hinman explained in his preface.

Such modesty is typical of postbellum authors. But Hinman also took pride in never completely conforming to the standards of the postwar genre in which he was writing, and hints of Si Klegg can be found throughout The Sherman Brigade. He could not resist inserting conversations in rustic dialects and avoided long discourses on “general movements and campaigns” because “that history has been written in a multitude of books.” In the end, Hinman estimated, “Not more than a dozen pages, in all, are given to general history.” Unlike other authors, he was conscious of his own place in this text. “I have told the story in a conversational ‘free-and-easy’ way, as we would talk around a camp-fire, with no attempt at literary excellence. I have made frequent use of the word ‘we’, which means all of us. An apology is here offered, should any deem it necessary, for the occasional appearance of the big ‘I’. In such a story it seemed impossible to avoid it.”

Hinman’s own experiences in the Sherman Brigade inspired Si Klegg. Just like Si and Shorty, the new Ohio troops of The Sherman Brigade learn to drill and march, encounter army rations for the first time, and over four long years of war become the weary and sardonic veterans they once hated. Even minor events in Hinman’s factual account echo the plot of Si Klegg. On his first march, a weary Si empties his knapsack and destroys a quilt his mother gave him so that it will not fall into the enemy’s hands. In The Sherman Brigade, Hinman tells of a friend who cut up his mother’s quilt before abandoning it, explaining that “no blasted Kentuckian is going to sleep under it.” Such anecdotes reveal the origins of Si Klegg‘s humorous realism. In fact, Hinman was more successful in creating a logical progression in Si Klegg by integrating these stories into a coherent narrative, rather than relating them as humorous hearsay in his regimental history.

The Civil War placed common men in uncommon times. When most postwar authors narrated the war, they produced epics of grand battles and grand generals set against the backdrop of a nameless mass of soldiers. But in both Si Klegg and The Sherman Brigade, Wilbur Hinman wrote the Civil War as most men experienced it. In these books, personal experience trumped omniscient narrative. And for a brief moment, the heroes of the war were not Grant or Lincoln or Lee, but that quintessential everyman, Si Klegg of the 200th Illinois Infantry, and the millions of other soldiers like him.

As the United States endured new wars in the twentieth century, Si and Shorty disappeared into the mass of post-Civil War literature. Perhaps Hinman’s book was discarded because, unlike The Red Badge of Courage, it failed to appeal to the disillusionment and modern aesthetic ascendant in the new century. Si Klegg enjoyed a brief midcentury revival, courtesy of literary scholars’ fascination with the sources for canonical works of fiction. Academics were drawn to The Red Badge of Courage as the single greatest work to treat the Civil War, and they accordingly sought out its factual origins. They found evidence for Stephen Crane’s inspiration among his teachers, family, and Civil War literature of the period. In 1939, H.T. Webster of Temple University suggested that Si Klegg may have been a prime influence on the young Crane. Webster argued that “Crane’s extreme youth … supports the belief that there is a single written source to which the work is mainly indebted.” Indeed, Si Klegg and The Red Badge of Courage share similar plot points, character types, symbolism, vernacular dialogue, and even the use of fictional regimental designations—Si Klegg’s 200th Indiana and Henry Fleming’s 304th New York—to avoid obvious historical references.

Unfortunately, these studies of master works tended to denigrate the books’ possible sources. Writing in 1958, for example, Harvard professor Eric Solomon identified Joseph Kirkland’s The Captain of Company K (1891) as a probable influence on The Red Badge of Courage, but felt obligated to conclude that Kirkland’s work was “a piece of hack writing by a crude technician who was primarily interested in supplying a stylized love plot with an honest background of war.” These sorts of evaluations often led to the rejection of original sources as legitimate books for independent study. Si Klegg was no exception, and after reappearing briefly as a foil for Crane’s masterpiece, the book fell back into obscurity. It was reprinted in the 1990s for the limited market of military historians and reenactors who appreciated the book’s attention to the minutiae of soldier life. After all, there are few other sources that deal so explicitly with how Civil War soldiers adapted to their new material environment—how they fried their salt pork, pitched their tents, and mended their clothes.

The same qualities that have relegated Si Klegg to the antiquarian niche market in the twentieth century guaranteed its mass market success in the nineteenth century. In the 1880s, publishers produced hundred of Civil War works, as veterans became memoirists and historians examined the conflict. But few of these books focused on the life of the average soldier in language that appealed to average readers. Even men whose military careers added little to the greater war effort filled their published remembrances with narratives of the movements of brigades and divisions in grand battles in which they played the smallest of parts. Many veteran-authors assumed that the minor aspects of their service—the same cooking, cleaning, and camping that Hinman reveled in-were of no literary interest.

Confederate veteran Carlton McCarthy published his memoir in 1882 with the express intent of recording some of these details. Like Hinman, McCarthy realized that such aspects of the war were completely foreign to a generation of readers too young to have served. “It is a common mistake of those who write on subjects familiar to themselves, to omit the details, which … are necessary to a clear appreciation of the meaning of the writer,” he explained. “This mistake is fatal when the writer lives and writes in one age and his readers live in another. And so a soldier, writing for the information of the citizen, should forget his own familiarity with the every-day scenes of soldier life and strive to record even those things which seem to him too common to mention.”

Wilbur Hinman may never have read the advice of his former enemy and fellow author, but he joined McCarthy in recording the forgotten features of army life. In the end, he was one of only a handful of authors to do so. Among these few was John Billings, whose Hardtack and Coffee, or the Unwritten Story of Army Life, published in 1887, was a journalistic parallel to Si Klegg. Like Hinman, Billings had served as an enlisted soldier in the war and also went on to write a more typical regimental study, The History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion. Billings too had been selected by fellow veterans to write this account of their service after publishing his first book.

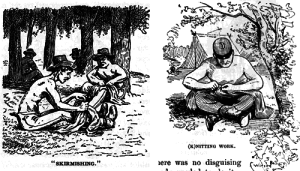

Hardtack and Coffee and Si Klegg both benefited from the work of illustrators who helped convey the daily occurrences of army life. This sort of cartoon illustration was relatively common in period newspapers but rare in printed historical books. Moreover, these illustrations also situated the books as vernacular accounts of the Civil War. Hardtack and Coffee was profusely illustrated by Charles W. Reed (1841-1926), who won the Medal of Honor while serving with Billings during the war. His rich wood-engraved illustrations complemented the narration of Hardtack and Coffee by adding visual details to an already journalistic account of soldier life (figs. 4a, 4b).

It is difficult to imagine Si Klegg without the humorous sketches accompanying the events described in the text. George Coffin (1850-1896) had been too young to be an active participant in the Civil War, but he had witnessed the wartime pomp of Washington, D.C., while a student at George Washington University. In the 1880s, Coffin worked as a staff artist at the National Tribune, providing the sketches that other workers converted into wood engravings and printed with the various stories running concurrently in the paper (fig. 5).

When Hinman left the paper and began work on his book, he also hired George Coffin to produce new illustrations for Si Klegg. Coffin executed his work for Si Klegg more carefully than the simple engravings that had appeared in the Tribune but still maintained the cartoonish humor he loved. In some cases, he recycled drawings which had already appeared in print. For instance, Coffin’s first sketch of soldiers battling a rainstorm appeared with a different story in the National Tribune before he drafted a similar wood engraving for the November 11, 1886, serial of “Si Klegg.” Coffin refined the image further for publication in Hinman’s book (figs. 6a-6c).

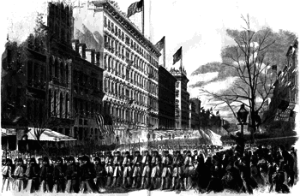

The decision to include so many unique images in Hardtack and Coffee and Si Klegg was a response to reader demand. The veterans who first met Si in the pages of the Tribune and later purchased Hinman’s book expected illustrations in their reading. Their experience of the war itself, moreover, had been shaped by visual media. When they first marched off to war, Union soldiers were already familiar with martial pageantry through illustrations. Popular prints had long featured military scenes, and the beginning of hostilities in 1861 prompted illustrated newspapers to devote page after page to depictions of war. A recruit thus entered the army with a set of ideas shaped by antebellum illustrations, and he continued to view his war in illustrated form. The Civil War saw the first widespread use of photography in a war zone, but other visual media played a more significant role in forming public conceptions of the conflict. Matthew Brady’s searing photographs of corpse-strewn battlefields only reached those who visited his New York gallery, but newspapers like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated and Harper’s Weekly circulated widely and featured detailed wood engravings prepared from firsthand sketches (fig. 7).

These wartime illustrations formed the popular perceptions of the army and its soldiers, from generals to privates, and they affected the soldier’s view of himself and the war he was fighting. Combat artists gradually shifted from portraying idealized martial scenes to depicting the non-combat aspects of soldier life. As members of a remarkably literate army, federal soldiers devoured both printed and illustrated war news. After the war, veterans regarded illustration as an essential part of any war literature. Rare is the postwar book which features no illustrations, although the quality varied dramatically. Few, however, feature the sketchy cartoons of Si Klegg and Hardtack and Coffee, or approach the number of illustrations contained in these works.

The same illustrations that ensured a positive reception among veterans helped attract civilian readers, and both Hardtack and Si Klegg were pitched to dual markets. John Billings wrote Hardtack and Coffee in part for those readers “to whom the Civil War is yet something more than a myth,” but what initially prompted his idea was the realization that a new generation of Americans was entirely ignorant of the realities of the conflict. Similarly, Hinman composed Si Klegg for veteran readers who were intimately familiar with military life, but it was not exclusively the domain of former soldiers. Because it was “possible that some may read this volume who have no experimental knowledge of life in the army,” Hinman explained, “the author has devoted pages, here and there, to information of an explanatory nature, which he hopes will assist them in appreciating, perhaps as never before, how the soldiers lived—and died.” In fact Hinman wrote his book and Coffin illustrated it in a way designed to be both attractive to and readable by young Americans. This was not solely because of the martial themes that boys of the era clamored for. Like so many of the books aimed at boys, Si Klegg features a conversational tone, comedic dialogue, slapstick humor, and just a touch of swashbuckling (in the form of a daring prison escape). In fact, Hinman’s book more closely resembles other works of boys’ literature than much of the post-Civil War military genre, and it was that much more appealing to young readers. Regimental histories and sweeping chronicles had far less to say to a new generation who had no personal connection with the war. But you did not have to be a veteran to enjoy Si Klegg—to see the humor in its illustrations or be enthralled by the detailed sections on lice-picking and sickening food. This is one of Hinman’s true triumphs. Si Klegg was endearing to both former soldiers, who could laugh knowingly and nod in remembrance, and non-veterans, who enjoyed the humor and discovered new and remarkable details of army life with every page.

Foremost among Si Klegg‘s fans, however, were the veterans of the war Hinman fictionalized. The National Tribune, where Si Klegg made his debut as a serialized hero, was a veteran’s newspaper with a massive audience. Hinman’s book, like the Tribune, was devoured by one of the core demographics of the last half of the nineteenth century. Nearly half of the adult men in the postbellum North had served in the Civil War, and their interests exerted substantial influence on social and political life. It was from the ranks of the foremost organization of these veterans, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), that Hinman drew the majority of his readers (fig.8).

Few features of the GAR are more apparent to our contemporary eyes than its nostalgia. As soldiers passed into middle age, they sought to define and understand the monumental events of their youth. For many veterans, the war was the single national event in otherwise local lives, and they became preoccupied with connecting themselves to the larger scenes of the conflict. It was precisely this impulse which led to the publication of hundreds of detailed unit histories, like Hinman’s own Sherman Brigade, which retrospectively mingled the history of a particular unit with the grander progress of the war.

In hindsight, veterans also viewed their military service as the epitome of youthful, masculine camaraderie. For many of them, the GAR represented an opportunity to relive the best aspects of army life. Veterans attended regular local meetings and massive annual national encampments. These events featured reenactments of every aspect of army life save actual conflict. GAR members ate army food in mess halls, sang military songs, smoked clay pipes, and slept in tents. This was a sanitized and romantic version of their experience, and it embodied the aspects of war that veterans preferred to remember. In the process of recreating the past, veterans also redesigned their memories of the war, suppressing brutal carnage and replacing it with grand strategic events and humorous anecdotes of camp life.

Si Klegg is a singular expression of this version of the Civil War. In his introductory note, Hinman extends “fraternal greetings to all his late comrades-in-arms” and expresses “the hope that they may find pleasure and interest in living over again the stirring scenes of a quarter of a century ago.” For Hinman and his fellow veterans, these “stirring scenes” did not involve carnage. Instead, it was the prosaic details of soldier life which inspired “pleasure and interest.” Si Klegg is full of comic misery, but steers clear of graphic violence. Towards the end of the story, Si and Shorty experience the horrors of a battlefield hospital and prisoner camp, but these are abbreviated vignettes. Hinman devoted an entire chapter to describing army rations and another to lice and other pests. His depiction of the field hospital, while graphic, lasts for only three pages of 700. Even Shorty’s death, in a final, fictional battle, comes as a natural conclusion and heroic end, rather than a terrible consequence of war.

Far removed from the war, veterans could enjoy humorous anecdotes of soldier life in all its dirty and miserable detail. Hinman knew not only the subjects these readers would appreciate but also those they would prefer to forget. Comfortably lounging in his fireside armchair, the veteran reader could recall the pleasures and even discomforts of army life with a sense of accomplishment and safety. He did not, however, care to relive the war’s carnage or invoke the lingering specter of death that had dominated soldier life.

Civil War veterans confronted the horrors of the war by redesigning their public memory of the experience. By creating an idea of the conflict centered on pure patriotism, humor, and camaraderie—an idea embodied in Si Klegg—they suppressed the Civil War’s brutality and abject horror. Hinman provided us with a textual version of this public memory: the Civil War as veterans wanted to remember it. Few veterans wrote about the violence of the war at any length. It is no accident that a young non-veteran wrote the book which scholars cite as the great fictional version of the war’s violence, terror, and reality: The Red Badge of Courage. Soldiers were happy to forget the darker facets of their war years. Just as impersonal, abstract regimental histories allowed veterans to understand their logistical place in the Civil War, Si Klegg let them read about the great event of their lives without confronting its more scarring aspects.

No postbellum book—fiction or nonfiction—can truly explain the personal experience of the Civil War. Veterans and nonveterans alike inevitably inserted something of their current selves into their depictions of wartime soldiers. Si and Shorty are not, in fact, examples of the “real” Civil War soldier. They are, rather, how the Civil War veteran chose to remember himself in hindsight, some two decades after the momentous national and personal events that defined his life.

Further reading:

Both Wilbur Hinman’s Corporal Si Klegg and his Pard and John Billings’s Hardtack and Coffee are available in a variety of reprinted editions. For Hinman’s other work, see Camp and Field. Sketches of Army Life (Cleveland, 1892) and The Story of the Sherman Brigade (Alliance, Ohio, 1897). John Billings also wrote The History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion (Boston, 1909).

For a Confederate take on everyday soldier life, see Carlton McCarthy’s Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865 (Richmond, 1882), also available as a reprint. Scholars who identified Si Klegg‘s possible influence on Stephen Crane include Eric Solomon in his article “Another Analogue for ‘The Red Badge of Courage’,” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 3.1 (June 1958): 63-67, and H.T. Webster in “Wilbur F. Hinman’s Corporal Si Klegg and Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage,” American Literature 11.3 (November 1939): 285-293. Stanley Wertheim argued for a broader view of possible sources in “‘The Red Badge of Courage’ and Other Personal Narratives of the Civil War,” American Literary Realism, 1870-1910 6.1 (Winter 1973): 61-65.

For dated but detailed studies of wartime literature and reporting, see Daniel Aaron’s The Unwritten War, American Writers and the Civil War (New York, 1973) and William Fletcher Thompson, Jr.’s The Image of War, The Pictorial Reporting of the American Civil War (New York, 1960). The best study of the Grand Army of the Republic is Stuart McConnel’s Glorious Contentment (Chapel Hill, 1992).

This article originally appeared in issue 11.2 (January, 2011).

Tyler Rudd Putman is a Lois F. McNeil Fellow in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware. He is currently researching slops—the ready-made clothing of early America—and the men who wore these garments.