Historians have long wondered what prompted President Thomas Jefferson’s cryptic sentence in a note dated January 13, 1807, to Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin: “The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I.” Given Jefferson’s opinion explicitly expressed elsewhere that women were best suited to domestic roles, not to boisterous public political forums, and not as actors in the halls and offices of government, scholars of the early republic and popular authors alike, since at least 1920, have tried to reconstruct the specific context in which the president made this comment. For the last twenty years, the consensus explanation has been that Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, unable to find enough qualified men to fill federal government jobs, proposed hiring women for those positions. However, while Jefferson’s statement may reflect his thoughts on women as office holders in general, my recent research in federal records proves that Jefferson wrote the sentence in reaction to Gallatin’s proposal to appoint a specific woman to a specific job.

Previous scholars’ attempts to explain Jefferson’s statement were foiled by the fact that Gallatin’s letter to Jefferson, which provoked the presidential response, has apparently not survived. Arsonists burned the Treasury Department offices on March 31, 1833, incinerating much of the department’s records, including letters to and from the collectors of customs. Despite the Treasury Secretary’s efforts to reconstruct the files with duplicate copies from elsewhere, most correspondence with the Collector of the Port (customs collector) at Wilmington, North Carolina, remains lost—and the Collector of the Port at Wilmington turns out to have been the key correspondent in this issue of appointing a woman to public office.

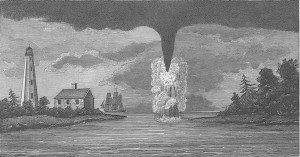

Clues to solving the mystery lie in the next sentence of Jefferson’s note: “Shall we appoint Springs, or wait the further recommendations spoken of by Bloodworth?” Timothy Bloodworth (1736-1814) was Collector of the Port of Wilmington, appointed by Jefferson in 1802. One of Bloodworth’s collateral duties as collector was to superintend the Cape Fear Lighthouse on Bald Head Island at the entrance to the port of Wilmington. As Superintendent of Lights, he nominated candidates for light-keeper to the Treasury Secretary, Gallatin. Probably due to the fire, documents of Bloodworth’s efforts to find nominees for the light-keeper appointment are largely lost to us, except four pieces of correspondence that escaped the flames and are now in three separate record series at the National Archives.

There was, indeed, a vacancy at the Cape Fear Lighthouse. The Wilmington Gazette of October 21, 1806, reported that five days earlier, a man named Joseph Swain, hunting deer and wild hogs on Bald Head Island, fired at a noise he heard in the bushes—only to find that he had killed his father-in-law, light-keeper Henry Long. This tragedy did not necessarily interrupt the function of the lighthouse, because light-keepers’ wives routinely helped their husbands tend the lights, and would operate them single-handedly in their husbands’ absence. In the intervening months between Henry Long’s death and President Jefferson’s appointment of a replacement keeper, it was most likely Rebecca Long, Henry’s widow, who kept the Bald Head lighthouse lamp clean, trimmed, and lit.

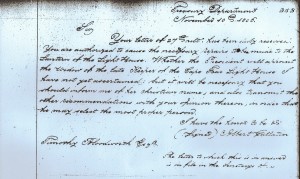

Collector of the Wilmington port, Timothy Bloodworth, wrote a letter (now lost) to Secretary Gallatin, on October 27, 1806. We can guess much of its content from Gallatin’s reply on November 10, preserved among “Lighthouse Letters” at the National Archives:

Your letter of 27th ulto has been duly received. You are authorized to cause the necessary repairs to be made to the Lantern of the Light House. Whether the President will appoint the widow of the late Keeper of the Cape Fear Light House I have not yet ascertained; but it will be necessary that you should inform me of her christian name; and also transmit the other recommendations with your opinion thereon, in order that he may select the most proper person.

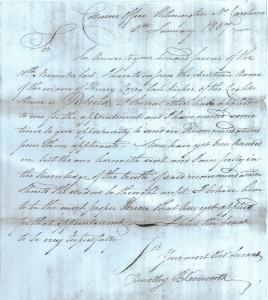

Bloodworth delayed replying to Gallatin until almost two months later, on New Year’s Day 1807. His reply forwarded the only other nomination for the vacancy, Sedgwick Springs, a Revolutionary War veteran and the Long family’s near-neighbor on Bald Head Island:

In answer to your honored favor of the 10th November last, I have to inform the christian name of the widow of Henry Long late keeper of the Light House is Rebecca. Several others had applied to me for the appointment and I have waited some time to give opportunity to send in Recommendations from those applicants. None have yet been handed in but the one herewith sent and I am fully in the knowledge of the truth of said recommendation[.] Should the widow be thought unfit, I believe him to be the most proper Person that has yet applied for that appointment.

When searching through this correspondence, I did not find the application “herewith sent” with Bloodworth’s letter. I suspected that, separated from the letter, it had perished in the Treasury Department fire. But about a year later, Thomas M. Downey, associate editor of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, sent me a copy of the missing enclosure, found elsewhere in the National Archives by a researcher for the Papers. The document is a recommendation from twelve Wilmington citizens, all men, dated December 1806, addressed to the President of the United States. It reads:

We the subscribers resident Citizens in the District and town of Wilmington being informed that Sedgwick Springs wishes to become a Keeper of the Light House on Bald Head (provided it should be thought the widow of the late Henry Long, inadequate to the safe keeping thereof) beg leave Hereby to Recommend the said Sedgwick Springs as a fit and proper Person to take charge and keep up the said Light—He being an old Inhabitant of the town of Wilmington a Sober Industrious Citizen having been employed for these eight Years last past and now is an Inspector of the Revenue in which Office he has ever behaved himself as a dilligent and Carefull Officer and to our knowledge conducted himself as a truly honest man in all his dealings—With great Respect We are Sir Your most Obedient Servants [signed Jno Walker and eleven others]

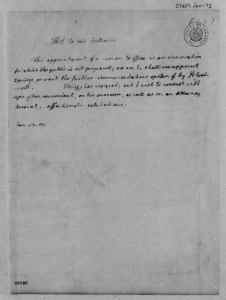

When Gallatin forwarded Bloodworth’s letter, with its enclosure, to the president, Jefferson promptly wrote the now often-cited reply to Gallatin, “The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I. Shall we appoint Springs, or wait the further recommendations spoken of by Bloodworth?” Jefferson’s consultation with Gallatin was brief and his decision swift. Two days later, on January 15, 1807, Gallatin replied to Bloodworth: “Your letter of the 1st Inst. has been received. The President of the United States has appointed Sedgwick Springs to be the Keeper of the Cape Fear Light House, of which you will be pleased to give him notice.”

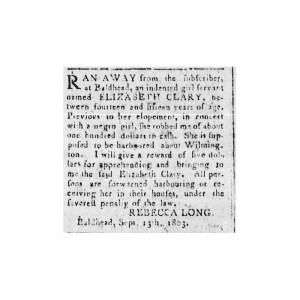

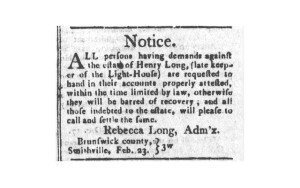

We know something of the woman, Rebecca Long, whose nomination Jefferson rejected, from public records and newspapers. According to a family historian, she was born Rebecca Hand about 1755 and married Henry Long in 1774 in Smithville District, North Carolina. The Wilmington Gazette of February 13, 1800, reported that Rebecca and her husband marched in a large procession of military and civilian mourners to attend a local funeral service for George Washington, who had died the previous December at his home in Mount Vernon. From the 1790 census we know that she employed the labor of at least one slave and from a newspaper advertisement we know she managed one indentured servant in her own household. She placed an ad in the Wilmington Gazette of September 13, 1803, seeking the apprehension and return of “an indented girl servant” named Elizabeth Clary. Long administered her husband’s estate after his death in 1806, taking out a notice to his creditors in the March 3, 1807, issue of the Wilmington Gazette. Rebecca Long reportedly died May 2, 1815, in Smithville, North Carolina.

Jefferson’s declaration that he and his public were “not prepared” for a woman to hold federal appointed office may have surprised his two long-time, politically astute associates, Timothy Bloodworth and Albert Gallatin. In the months after Henry Long’s death, they were willing to support his widow as his replacement (or they would not have forwarded the suggestion)—and the twelve Wilmington men who petitioned Jefferson on behalf of Sedgwick Springs explicitly made their recommendation contingent on the unfitness of Rebecca Long. Why did they all or any of them not foresee Jefferson’s adverse reaction, if indeed the general public was so averse to the notion of a female light-keeper?

For his part, Jefferson saw no place in public life for women, arguing that nature had “marked infants and the weaker sex for the protection rather than the direction of government.” But, unlike some appointed officials actively engaged in public life and policy decisions, a light-keeper was a civil servant ensconced within the thick walls of a remote lighthouse, far removed, practically and geographically, from the administration of government. What was more, the work of a light-keeper (cleaning the light, trimming the wick, and fueling the lamp) was quite similar to the kinds of work that women already did in their own houses. Indeed, people in the early republic saw light-keeping as domestic work requiring no manly skill or masculine strength. Therefore, according to historian Virginia Neal Thomas, “many keeper positions were filled by veterans, debilitated men, [and] unskilled political appointees.” Women performing such work were not the “innovation” that Jefferson feared.

Jefferson might have been unaware that, prior to his administration, at least three women had served the public quite satisfactorily as postmasters in the United States. The postmaster job required business competence, financial accountability, and daily personal interaction with the public, making his claim that women in federal office were “an innovation for which the public is not prepared” seem, at best, uninformed. Perhaps Jefferson was less concerned with the suitability of a woman to the work than with possible political objections to Rebecca Long’s nomination; the federal government at the time had less than 3,000 civilian employees (including forty working in lighthouses and navigation), most of them appointed by the president. People of Wilmington who had advocated for Long’s worthiness might have applauded her appointment, but since Revolutionary War veterans were still a numerous voting constituency who benefited from light-keeper appointments, perhaps Jefferson meant that women appointees as light-keepers were an innovation that opportunistic veterans might resent.

In 1826, almost twenty years after Jefferson had rejected Rebecca Long’s nomination, President John Quincy Adams appointed the first federally employed female light-keeper. By then, politicians’ need to place veterans in these posts likely had grown less pressing as the Revolutionary generation died out. From 1826 to 1859, the federal government appointed fifty-three women—about five percent of all principal light-keepers appointed during that time; most (81 percent) were widows who succeeded their deceased husbands. They not only knew the job—which they learned, like many women in other trades, from helping their husbands—but, as widows, benefitted from the earnings lighthouse-keeping generated. Perhaps if Jefferson had seen—as Bloodworth, Gallatin, and twelve petitioners from Wilmington did—that presidential appointments could work as beneficially for worthy, disadvantaged women as they did for men, Rebecca Long might have been first in that long line of light-keepers’ widows to a receive federal appointment.

Further Reading:

Jon Kukla, Mr. Jefferson’s Women (New York, 2007).

Virginia Neal Thomas, “Woman’s Work: Female Lighthouse Keepers in the early Republic, 1820-1859” (MA thesis, Old Dominion University, 2010).

Information about Rebecca (Hand) Long’s birth, marriage, and death were gleaned from Jean Hirsch, comp., “Family of Winifred Mae Taylor Mayo.”

Sedgwick Springs’ application for a Revolutionary War pension, published in NARA, National Archives Publication M804, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, roll 2262, is conveniently transcribed online at “Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters.”

A U.S. Postal Service history of women postmasters is here.

Previous published explanations of Jefferson’s remark include: James Morgan, “Women in Politics,” Journal of Education 92:17 (November 11, 1920): 461, claiming Gallatin proposed “a woman clerk in the treasury”; Rosemarie Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia, 2007), who asserted that Jefferson vetoed a proposed “postmistress”; William K. Bottorf, Thomas Jefferson (Boston, 1979), who stated that Jefferson wrote this famous line to Abigail Adams; and Jay C. Heinlein, “Albert Gallatin: A Pioneer in Public Administration,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 7:1 (January 1950): 69-70, suggesting that Gallatin considered women a “possible source of talent” to fill underpaid federal jobs.

Probably building on Heinlein’s suggestion, Joyce Appleby propounded the most influential theory to explain Jefferson’s statement, beginning with her article, “Introduction: Jefferson and His Complex Legacy,” in Peter S. Onuf, ed., Jeffersonian Legacies (Charlottesville, 1993). Appleby stated, “Worried about the pressing shortage of first-rate talents for government office, Gallatin suggested naming women to certain posts.” Appleby reiterated the same explanation in Jefferson: Political Writings, eds. Joyce Appleby and Terence Ball (Cambridge, England, 1999); Joyce Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution: The First Generation of Americans (Cambridge, Mass., 2000); Joyce Appleby, “Thomas Jefferson: 1801-1809,” in Alan Brinkley and Davis Dyer, eds., Reader’s Companion to the American Presidency (Boston, 2000); Joyce Appleby, Arthur M. Schlesinger, general editor, Thomas Jefferson: The American Presidents Series: The 3rd President, 1801-1809 (New York, 2003); and Joyce Appleby, “Thomas Jefferson,” in Alan Brinkley and Davis Dyer, eds., The American Presidency (New York, 2004).

For Appleby’s influence in popular history, see Cokie Roberts, Ladies of Liberty: The Women Who Shaped Our Nation (New York, 2008). Writers who cite no source for their elaborations on the Appleby thesis include: Susan Dunn, ed., Something that will Surprise the World: The Essential Writings of the Founding Fathers (New York, 2006); and Christopher Phillips, Constitution Cafe: Jefferson’s Brew for a True Revolution (New York, 2011).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.4 (Summer, 2015).

Public historian David E. Paterson studies Upson County, Georgia, especially the local history of slavery and Reconstruction. A civilian employee of the US Navy by day, he spends his leisure hours researching and writing history—especially mini-biographies of enslaved Upson County residents—and managing the Slave Research Forum at AfriGeneas.com. He is the author of A Frontier Link with the World, Upson County’s Railroad (1998), and editor of the autobiography of Houston Hartsfield Holloway, In His Own Words: Houston Hartsfield Holloway’s Slavery, Emancipation, and Ministry in Georgia (forthcoming from Mercer University Press, November 2015). Paterson lives in Norfolk, Virginia.