Weaving the Wicked Web of Antebellum Religion and Politics

“Douglas is a cuning dog & the devil is on his side,” wrote Abraham Smith to Abraham Lincoln in the summer of 1858. One month earlier, the Republican Party of Illinois had decided to run Lincoln for the Senate against Stephen A. Douglas, the incumbent Democrat. Smith, an Illinois farmer, encouraged Lincoln to take “the high ground” during the campaign. He called upon Lincoln to remind all who would hear that “the bible teaches the same that is taught by the declaration of Independence—by the Constitution of the U.S. and by the fathers of the republic.” What others might view as separate strands of “religion” and “politics,” or “church” and “state,” Smith wove together tightly. For him, the Bible, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Founding Fathers constituted one holy garment. The Lincoln-Douglas struggle, moreover, was much more than just another political event that pitted two men against one another for a legislative position. The race signaled forces higher and lower, lighter and darker. “As I view the contest (tho we say it is between Douglass & Lincoln—) it is no less than a contest for the advancement of the kingdom of Heaven or the kingdom of Satan.”

Publicly, Lincoln neither elevated nor lowered the electoral stakes to those realms. Before and after receiving Smith’s letter, however, he did reference Satan during the campaign. For Lincoln’s campaign acceptance speech in June 1858, he borrowed from the Bible the line that came to serve as the speech’s unofficial title: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” This was both a statement about the state of the Union and a warning of what could befall the United States if it failed to resolve the imbroglio over admitting new states as either free or slave. Lincoln and most of his audience knew “the house divided” reference well. Recorded in three of the Bible’s gospel narratives, it began with Pharisees accusing Jesus of being in league with the “prince of devils.” Jesus replied, “How can Satan cast out Satan? … if a house be divided against itself, that house cannot stand. And if Satan rise up against himself, and be divided, he cannot stand.” On one hand, Lincoln used this biblical tale as a template for contemporary political divisions. On another veiled hand, the congressional aspirant lodged devils and concerns over devils within the rhetorical architecture of his allusion.

Privately and publicly, implicitly and explicitly, aurally and textually, the kingdom of Satan seemed more than present. It appeared to be spinning the nation into chaos.

During the ensuing Lincoln-Douglas debates, Douglas pilloried Lincoln for his “House Divided” speech. Lincoln avoided mentioning or invoking Satan throughout the summer and fall. That was until the final debate. In Alton, Illinois, Lincoln quoted the “House Divided” speech and acknowledged that the words and spirit of it “have been extremely offensive to Judge Douglas.” The Democrat, Lincoln exclaimed, “has warred upon them as Satan wars upon the Bible.” According to the local newspaper, after Lincoln likened Douglas to the devil, the crowd erupted in “laughter.”

In this political contest of 1858, Satan was woven into the fabric of political discussions in ways stark and subtle. Abraham Smith maintained that the electoral process manifested the war between the “kingdom of Heaven” and the “kingdom of Satan.” Lincoln’s most noteworthy speech was premised upon demonic discussions. When mapped onto the United States, the “house divided” line hinted at the presence of darkness in American political culture. When Lincoln later associated Douglas with Satan, it sounded like a joke to some. Privately and publicly, implicitly and explicitly, aurally and textually, the kingdom of Satan seemed more than present. It appeared to be spinning the nation into chaos.

Looking first at the devil broadly in antebellum society and then specifically at mentions of Satan in the governmental place Lincoln hoped to get in 1858—Congress—this essay suggests that Satan simultaneously tightened and troubled religion, politics, and the meshing of them in the antebellum age. At one level, Americans put Satan to work as a means to denounce their political opponents. In an era marked by political party chaos and reorganization, raising the devil was a means of political differentiation. It also transformed the stakes of debate. By tying otherworldly dimensions to this-worldly concerns through references to Satan and Satan’s kingdom, Americans acknowledged that perhaps otherworldly forces were unmaking their this-worldly projects and programs.

Conjuring the devil rhetorically and visually signaled much more. Satan troubled senses of political and spiritual progress. The devil’s past havoc both on the earth and beyond it suggested that the present and future United States was in deep and dark trouble. As Satan moved from the margins of American politics to its center by the time of national fracture in 1860-61, the nation’s elected officials seemed to indicate that neither they, nor their God, were in control. “Manifest destiny,” that widespread belief that heavenly providence shined upon the United States, had given way to the malevolent disruptions of the kingdom of Satan in America.

“Devils Dressed in Angels’ Robes”

Satan and his minions could be seen, heard, and discussed widely in the decades before the Civil War. From the writings and artwork of reformers to the political prints and speeches of the era, the forces of radical evil were on the move. By the time of the Lincoln-Douglas debates and the ensuing Civil War, when Abraham Smith perceived a contest between the “kingdom of Heaven or the kingdom of Satan,” it appeared to many Americans that Satan had set his cloven feet on the soil of the United States. Many Americans were not passive observers in Satan’s rise. They conjured the dark prince into American domains through their writings, artwork, and speeches.

At times, antebellum artistic culture seemed obsessed with darkness. The gothic stories of Edgar Allan Poe and the art of Thomas Cole embraced the dark sides of humanity and nature. Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville populated their novels and short stories with demonic characters and forces, while the revealed scriptures for the new Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Book of Mormon and the Book of Commandments, included prominent roles for Satan and several antichrist characters both in the ancient past and for the American present.

Although antebellum reformers and reform organizations criticized some of these dramatic renderings of evil, they too conjured hell’s angels for their own purposes. The number of reform organizations and their membership rolls swelled during the first half of the nineteenth century. So too did their invocations of the devil and the demonic. Temperance advocates, for instance, damned “demon liquor” and “demon rum.” When businessman and reformer Lewis Tappan encouraged revivalist Charles Finney to carry the gospel to the notorious Five Points of New York City, he explained that Finney would be “rescuing from Satan one of his haunts.”

Abolitionists and women and men formerly held in bondage energetically invoked demons, devils, Satan, and hell. When Frederick Douglass denounced the “religion of the South” in his autobiography, he wrote that it was “a mere covering for the most horrid crimes.” This so-called religion was in fact “a dark shelter under, which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal deeds of slaveholders find the strongest protection.” He concluded that in slavery “we have religion and robbery the allies of each other—devils dressed in angels’ robes, and hell presenting the semblance of paradise.” William Lloyd Garrison denounced the Constitution as an “agreement with hell” and then performed on a copy of it what happened to bodies in hell. He burned it.

“My singularity is that when I say that Freedom is of God, and Slavery is of the devil, I mean just what I say,” Garrison wrote on another occasion. In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and popular theatrical adaptions of it, the forces of evil seemed hell bent on the destruction of African Americans’ lives, families, and faiths.

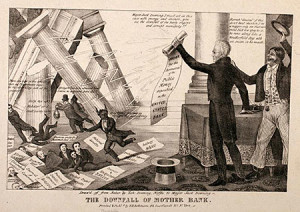

Satan and other renderings of the demonic played important roles in the visual culture of antebellum political discussions as well. One popular print from the early 1830s, “The Downfall of Mother Bank,” showcased President Andrew Jackson destroying the National Bank. In the middle of the melee, as Whig politicians cower amid tumbling pillars, one figure with darkened skin, horns, and a tail races away from Jackson. “It is time for me to resign my presidency,” this character exclaims so that viewers could recognize who this devil had been in his human disguise. It was none other than Nicholas Biddle, the president of the downfallen bank. Only through Jackson’s political heroism was Biddle exposed and exorcised.

Twenty years later, as antislavery forces were in the process of painting the peculiar institution as built upon hell, proslavery forces (or at least anti-antislavery contingents) struck back. In response to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, one artist pictured a “dream” wherein either Stowe was in hell, or hell had invaded the United States. This busy satirical print features a host of devils, beasts, serpents, and Medusa-type characters. At the center, a black man stands holding a flag emblazoned with the words “Women of England To the Rescue.” To his right and below, Stowe holds an illustrated copy of her novel. Devils harass her. They poke and prod her. One fixes a chain to her feet. They appear to be dragging her into an “under ground railway,” perhaps linking the secretive American route of liberation with the assumption that hell was a space under the ground.

Beyond the overt denunciation of Stowe and her novel, this “dream” disclosed several important elements in antebellum religion and politics. It tied biblical imagery to the past, present, and future through an overflowing abundance of violent evil. Devils carry pikes and battle flags. Others beat drums of war. A cannon fires at Stowe. From above, a many-headed dragon spews fire in its descent. The apocalypse of Revelations has been unleashed. Evil seemed to be coming from all temporal and geographical directions: under the ground, the sky above, the biblical past, and the prophesied future.

This “dream” signaled a change in American political culture. While references to demons and Satan had been a part of politics in the United States from its beginning, devils did more than move from margin to center. They overwhelmed the stage. In “The Downfall of Mother Bank,” the horned Nicholas Biddle was but one small character. By the 1850s, devils were unavoidable. The kingdom of Satan was present and abundant. It overflowed. It overran the confines of hell and poured itself upon Americans and into the United States. The kingdom of Satan wreaked aggressive violence; and, in the case of this anti-Stowe print, it appeared to perform valuable service. Demons chained the proslavery nemesis. Visual artists, moreover, were not the only ones dreaming of Satan in their midst. Elected officials were, as well, and they conjured the kingdom of Satan in the capital of their own kingdom: the halls of Congress.

The King of Hell in the Halls of Congress

As antebellum Americans incarnated the devil visually and rhetorically to address the central topics of their day, the nation’s leading politicians ushered Satan into their domain. They did so, in fact, with increased frequency. In the seventy years from the founding of the United States government under the Constitution to the severing of the union with the Civil War, Satan moved from a peripheral performer in governmental discussions to a star on the center stage. Demonic invocations showcased how the Senate and the House of Representatives served not only as hubs of national legislation and political discussion, but also as locales of religious debate and discussion. In the buildup to the Civil War, these political representatives voiced what Abraham Smith feared in his 1858 letter to Abraham Lincoln: the kingdom of Satan had arrived and was on the march.

The number of references to “Satan” in the congressional records suggests that vital changes had occurred in the realms of and connections between religion and politics. Before 1826, members of the Senate and the House of Representatives rarely uttered the word “Satan.” They did so only three times in the thirty-five years from 1790 to 1825. Then, from 1826 to 1849, the number of discrete mentions rose to thirty-nine. That number was equaled in the next ten years. From 1850 to 1860, “Satan” was once again spoken thirty-nine times. Put another way, while congressmen used the word “Satan” once every decade in the early republic, they invoked him once every three to six months in the years before the Civil War. The king of hell seemed to find an audience in the antebellum congresses.

Congressional references to Satan had two main sources: the Bible and John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). When legislators used biblical texts related to Satan, they emphasized temptation and disruption. The serpent in the Garden, assumed to be Satan, helped cause the fall of humankind. The devil wreaked havoc on Job and his family. Satan appeared to Jesus and tempted him three times. Milton’s Paradise Lost was common reading for educated Americans. In it, Satan and his angelic co-conspirators failed to overthrow God and were then banished to hell. From there, Satan escaped and bedeviled God’s highest creation: Eve and Adam. Most often, Americans found political and religious meaning within Paradise Lost. It was a tale that linked this world with ones beyond it through narratives of treason that resulted in chaos, misery, and exile.

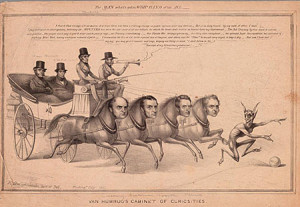

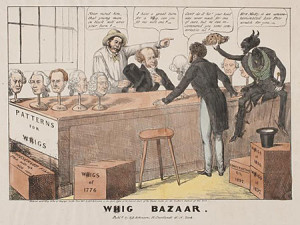

The disruptive character of Satan matched the political party chaos of the antebellum age. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, the Republican Party, which had destroyed its Federalist rivals and dominated national politics, died. In its place, Andrew Jackson’s coalition of Democrats arose and in opposition to them a new alliance emerged called the Whig Party. Then in the 1850s, it fell to pieces. Rival parties developed, most notably the American Party (oftentimes called the Know Nothings) and then the new Republican Party to which Abraham Lincoln shifted his allegiances from the Whigs. The presidential elections of both 1824 and 1860 signaled the party confusion, as four main candidates vied with each one, rather than the typical two. Amid this political disarray, Satan seemed an apropos symbol.

Although congressmen referenced Satan more often in the 1830s and the 1850s, important differences marked the decades. In the 1830s, invocations of Satan primarily circulated around issues of executive and federal power. Satan was mentioned in terms of executive vetoes, the place of the U.S. Bank, tariffs, and nullification of federal laws by individual states. During the 1837 economic depression, for instance, Henry Wise of Virginia referenced a description “of Satan” from John Milton’s Paradise Regained to denounce “the wicked intent of wedding the money in Government with the political power of the Executive.” If “the people” did not “start back affrighted and appalled” by how Jackson and his presidential successor, Martin Van Buren, had devastated the nation financially through their economic machinations, then, once more quoting Milton, “God hath justly given the nation up / To thy delusions, justly, since they fell / Idolatrous!”

In the 1850s, however, one topic overshadowed the others, and it was an issue for which Congress had direct responsibility: slavery in the territories. Following the annexation of Texas (1845), the Mexican-American War (1846-1847), and the California Gold Rush (1848), Congress had to address western lands at a speed more rapid and a geographical range more expansive than ever before. As hundreds of thousands of people moved within the nation and from the world to the United States, congressmen had to determine how the territories would be organized, what they would be politically during their time as territories, and whether their proposed constitutions for statehood would be acceptable. In many ways, the political shape and fate of the western lands resided in the halls of Congress.

For some legislators, the only analogue they could find for the political complexity was in the various moments of chaos wrought by Satan. In 1848, as congressmen debated the organization of Oregon as a territory, Robert M.T. Hunter of Virginia fretted that if slavery were barred from the beginning, “All considerations of the general interest would be sacrificed and merged in the spirit of hate.” This, he prophesied, would lead to a “civil war … not with arms, but under the forms of law.” To comprehend this future, Hunter knew of nothing “parallel” from the past. “[W]e must leave the realms of history for those of fiction,” he explained to his fellow congressmen. “We must turn to the gloomiest conception of Milton, who makes his Satan address ‘old night and chaos,’ and promise to extend their reign at the expense of light and life.”

Six years later, when congressmen debated placing territorial decisions related to free or slave status with statehood within the hands of local residents with the proposed Kansas-Nebraska Act, Thomas Davis, an Irish-American Democrat from Rhode Island, saw in it the wicked design of slave holders. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which would nullify the earlier Missouri Compromise that had forbidden slavery from these geographical regions, was to Davis simply a way for slavery to outflank freedom. It was akin to “Satan, entering Paradise, / ‘At one slight bound high overleaped all bound.’ … So slavery, at one bound, overleaps all rights, and subverts the whole foundation on which the moral universe stands. All is chaotic, ‘without form and void.'”

Davis was far from the only congressman to voice the sense that “[a]ll is chaotic.” The rise of references to Satan helped heat the tensions of the era as Democrats, Whigs, and Republicans used Satan to describe and denounce their opponents. In 1850, Democrat John R. J. Daniel of North Carolina referred to the hopes of “free-soilism” to keep slavery from the West as “personified and likened to Satan tempting our Saviour on the Mount.” Two years later, Charles Sumner, a Whig who vehemently opposed slavery and became a leading Republican, condemned the new Fugitive Slave Clause of 1850 by asserting that the Founding Fathers opposed slavery and its Satanic resonances. “Our fathers did not say, with the apostate angel: ‘Evil, be thou my good!’ In another spirit they cried out to slavery, ‘Get thee behind me, Satan!'”

Beyond religiously dramatizing political differences and legislative possibilities, references to Satan also allowed congressmen to move in a number of temporal and geographical directions to make their points. The disruptiveness of Satan gave congressmen a usable analogy to make sense of the disrupted state of American politics. In their efforts to comprehend and categorize contemporary problems in this way, however, legislators seemed to acknowledge that the nation and its governance were spinning out of control. As congressmen relied on Satan to cross time and space, to connect this world to others, and to configure what was happening in the United States vis-à-vis the actions of nonhuman forces in the past and present, they put on display their own political fragility. When it came to Satan, nothing appeared to be stable: time, geography, the republic of the United States, or the kingdoms of heaven or hell. Invoking Satan did not engender order; it energized disorder.

For some congressmen, contemporary events seemed to burst the bounds of human history and categorization. In 1858, after proslavery forces in Kansas had engineered a proslavery constitution and submitted it to Congress, Henry Bennett of New York maintained, “The offer contained in this act has no precedent or parallel. The only thing resembling it occurred more than eighteen hundred years ago.” At that time, “Satan tempted our Savior, and offered Him all the lands they beheld from the top of ‘an exceedingly high mountain,’ if He would fall down and worship him.” In the contemporary United States, Satan “made very much such an offer as this act makes to the people of Kansas, if they will fall down and worship slavery.”

Perhaps better than any other legislator, Jeremiah Clemens laid bare how efforts to harness Satan created their own kinds of chaos. A Democrat from Alabama who had fought in the Mexican-American War, Clemens took the floor in 1853 to discuss a resolution that called for Americans to participate in an international convention to discuss the fate of Cuba. Some southern whites had advocated annexation of the island. They viewed it, like the western lands, as another place within the nation’s manifest destiny, and these southerners wanted to make certain that American slavery would be part of the agenda. In his response, Clemens put to work such an abundance of analogies that it seemed an anarchy of explanation.

Clemens wanted nothing to do with another land grab, and in his adversarial speech, he roamed rapidly and wildly across space and time. “It is not in the book of Revelations that we are taught to covet the goods of our neighbors,” Clemens exclaimed, invoking and then rebuffing biblical prophecy as a means to determine what the United States should do in the future. Instead, Clemens looked backward to the Mosaic Decalogue and its “thou shalt not covet” refrain. To desire Cuba, Clemens insisted, would invariably lead to “a lawless spirit of war and conquest.” It would be “barbarism.” Searching for an historical analogy, Clemens maintained that if the American people sent troops there, they would be “[l]ike the Prophet of the East, who carried the sword in one hand and the Koran in the other.” Muslims and the Koran, however, simply manifested in the past the powers Satan wielded in the past, present, and potential future. Invading Cuba in the fashion of Muslims, Clemens concluded, “is a species of progress which Satan himself might fall in love.”

Clemens moved across time and space dramatically. He invoked Revelations and the Ten Commandments, Muslim history and contemporary American politics. Even more, Clemens suggested that Americans could outdo Satan, perhaps even tempt the devil. This manifest destiny was malevolent destruction. It was chaos and anarchy. This “progress” was the type “Satan himself might fall in love.” Amid the abundance of imaginative crossings of space and time, Clemens maintained not only that supernatural evil could affect human communities, but also that contemporary nations could influence the supernatural figure of Satan.

While most legislators used Satan to discuss elements within the United States, at least one projected his consideration of human history onto the supernatural domains. John Pettit, a Democrat from Indiana, expressed horror that if the United States listened to antislavery forces and liberated the enslaved, the nation would devolve rapidly: “As soon as you equalize different races of men in one country so soon do you commence the work of annihilation and destruction.” Pettit blamed the fall of ancient Rome on racial equality and maintained that such changes in the United States could wreak a “chaos on earth that was worse than the contention in Heaven.” That “contention in Heaven” was when Satan led an army against God. Of the earlier supernatural squabble, Pettit guessed that racial difference drove that discord as well. “I would be hardly willing to doubt even upon the best authority which exists, that Satan himself was of a different race from the other inhabitants of Heaven with whom he warred.” Whether on earth, heaven, or hell, Pettit concluded, “Races cannot, and will not, live together.”

Satan seemed omnipresent, pulling congressmen from the past to the present, from heaven to hell. In one speech, Satan even moved from a poignant metaphor to a prime mover, and that speech was one of the most important in American history: Charles Sumner’s “The Crime Against Kansas.” During two days in May 1856, Senator Sumner explained to his colleagues that while most legislative business over “[t]ariffs, army bills, navy bills, land bills, are important,” they and decisions made about them did not determine the overall well-being and functioning of “the State.” Recent events in Kansas, however, were of a different order. The violence and political malevolence there had the potential to destroy the nation. The power behind the disorder was slavery, and the power behind it was Satan. “One Idea has been ever present,” Sumner raged, “as the Satanic tempter—the motive power—the causing cause.”

When Sumner linked the “Satanic tempter” to “the causing cause,” the congressman gestured toward something much deeper than demonization of a political opponent. He lodged the legislative and territorial problems with nonhuman forces. Sumner placed into the hands of Satan the movement and momentum of the nation. While politicians may be the ones debating and making legislation and while border ruffians and antislavery activists in Kansas may be the ones shooting one another, the “motive power” came from an other-than-human figure: the Satanic tempter.

Sumner’s speech drew attention then and later because of the events that followed. During the speech, Sumner had lashed out at Stephen A. Douglas and Andrew Butler of South Carolina. Taking umbrage at the insults, Butler’s nephew Preston Brooks, a member of the House of Representatives, proceeded to beat Sumner with a cane. Sumner was so injured that it took four years until he returned to the Senate. Brooks became a hero to many in the South, while the “caning of Charles Sumner” energized northern Republicans to establish themselves as the only “civilized” political party that could stop the violence of the Democrats.

The caning kept Sumner from the Senate, but it did nothing to contain Satan. Democratic congressmen hit back rhetorically. They predicted war and saw both the kingdoms of God and Satan working together to bring it. John Savage of Tennessee feared in 1856 that war was imminent. “Can it be, that, in the early morning of our national existence, the wrath of an offended Heaven is to be visited upon us?” Or were the threats from another supernatural force? “[M]ay we not believe that the prince of darkness, attacking our early weakness, as he did our first parents in the Garden of Eden, let loose this odious brood of the internal world, to destroy a Government whose progress to greatness will banish discord and tyranny from the world?” This “odious brood” had leaders, and Savage named them: William Henry Seward and Charles Sumner.

Neither Savage, nor savage violence, had the last word when it came to Sumner or slavery. After a four-year absence after his beating, Sumner returned to Congress in the summer of 1860. Even as the nation crumbled, he held fast to his earlier position. “I oppose the essential Barbarism of Slavery,” he told his colleagues in June 1860, “whether high or low, as Satan is still Satan.” By the time of the Civil War, to hear “Satan” uttered in rapid succession in Congress was nothing new. The nation’s political halls had become a throne room for the king of chaos.

Two years earlier in 1858, the kingdom of Satan had prevailed over the kingdom of Heaven, or at least that was how Abraham Smith would have interpreted Stephen A. Douglas’s senatorial victory over Abraham Lincoln. Now in 1860, Lincoln defeated not only Douglas, but also two others who vied for the nation’s top office. In early March 1861, Lincoln became president and in his inaugural address argued that the “better angels of our nature” could save the nation. A few weeks later, but before the Civil War unleashed a different set of angels within the nation, composer Jupiter Z. Hesser wrote to Lincoln with conditional exultation. “Victory is ours, if we show satan the allmighty sword of Justice.” In political defeat and now victory, Lincoln was no stranger to statements about Satan. For his four years as president, the sword most certainly came. One hundred and fifty years after he was cut down, the nation still waits for almighty justice to banish from its midst the kingdom of Satan.

Further reading

W. Scott Poole, Satan in America: The Devil We Know (Berkeley, Calif., 2009); Andrew Delbanco, The Death of Satan: How Americans Have Lost the Sense of Evil (New York, 1995); Edward J. Blum, “‘The First Secessionist Was Satan’: Secession and the Politics of Evil in Civil War America,” Civil War History (September 2014): 234-269; Richard J. Carwardine, Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (New Haven, Conn., 1993); Amanda Porterfield, Conceived in Doubt (Chicago, 2012).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3 (Spring, 2015).

Edward J. Blum is professor of history at San Diego State University. He is the author of several books on race and religion throughout American history. Most recently, he co-authored with Paul Harvey The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America (2012).