In May of 1837, William “Billy” Douglas, a prosperous farmer and landholder in Bath County, at the southern end of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, died. A man of large appetites and little schooling, he was well-adapted to Virginia’s mountain frontier in the early nineteenth century and he acquired property and children with equal energy. His will, which he signed with an X, described his extensive acreage along the Cowpasture River in Bath County that included at least two farms, and 30 slaves, all of which he distributed among the thirteen children he had locally with three women, for none of whom is there any record of a marriage. One of those children, among the last six born, was Juliet Stewart, a young woman recently married to Adam Stewart. To her he left a “negro girl named Emiline,” aged seven; Juliet also acquired Nancy, aged five, in a general distribution of Douglas’ slaves. To Juliet’s younger sister, Mary, just fourteen, he left a “negro boy named James” and Levi, acquired in the general distribution.

Sometime soon after the death of William Douglas, Adam Stewart died, and Juliet Stewart married Jonathan Lemon in 1840 (figs. 1, 2). With this marriage, Jonathan Lemon acquired valuable property in Bath County as well as his wife’s slaves and a share in the Douglas home farm. In 1843, Lemon received a land grant for 297 more acres on the west side of the Cowpasture River, next to land owned by Henson Douglas, Juliet’s brother. Despite this promising situation, by 1852 Jonathan Lemon was dissatisfied and decided to sell out and move to Texas. In September 1852, he sold four tracts of land near the Cowpasture River to Jacob Simmons, who had married Juliet’s sister Mary in July 1848.

By the time of her marriage, Mary Douglas had owned James and Levi for ten years, and the young men were relatively satisfied with their situation. They were confident enough in their positions to ask Mary Douglas not to marry Jacob Simmons, as he had a reputation as a hard master. But marry him she did. Two years after the marriage, Simmons—who was aware of the two young men’s long-time animosity toward him—sold James and Levi to a slave trader passing through with a slave coffle. Levi and James had anticipated their sale once Simmons became their master and, according to one account, acquired forged free papers. The young men persuaded the slave trader that they did not need shackles, as they were happy to leave Simmons. Then, as the coffle moved down the road, they jumped over a fence and disappeared into a wooded area that they knew well.

Mountainous, rural, and losing population, Bath County might reasonably be seen as having an isolated enslaved population, unaware of escape routes to the North or upheavals in Virginia state politics. But Bath County contained slaves hired from as far away as Richmond to work at the inns, hotels, and stables around the mineral springs that gave the county its name and housed southwestward migrants to Kentucky and beyond. Enslaved people in Bath County were not isolated from the currents of information, gossip, and rumor that kept African Americans aware of important national and local events. In an account given to a New York City newspaper some two years later, Levi said he and James knew that two cousins who had escaped from Bath County earlier were in Malden, an Ontario town near the border with Michigan. They believed their best chance to join their cousins was to walk west and cross the Ohio River.

To call the events in the Lemmon case melodrama is not to diminish their contemporary power, but to enhance it.

Promising to meet in Malden if they were separated, they made their way northwest through the mountains, most likely following the turnpike that went from Staunton, Virginia, near Bath County to Parkersburg, Virginia, on the Ohio River. They were not far from the Ohio River when they were identified as escaped slaves and chased. James escaped, but Levi was caught and held in a county jail where, “being an excellent dancer,” the jailer invited local whites to watch him dance. In a newspaper account in late 1852, Levi, now calling himself Richard Johnson, said that he had escaped by giving the jailer, a heavy drinker, the money tossed to him for dancing. The jailer spent the money on liquor and fell asleep inebriated, allowing Levi to escape and reach the Ohio River, crossing it to relative safety in Ohio.

There Levi was aided by agents and sympathizers with the Underground Railroad to get to Cleveland, where he worked as a waiter in a hotel, then continued to Malden, Ontario, where he found James Wright already established and found his two cousins as well. By the summer of 1852, he had returned to the American Hotel in Cleveland in order to earn money to purchase land in Canada.

This was the first act of a long-running drama of American slavery and resistance in the 1850s. During that decade, proslavery and antislavery partisans labored steadily and creatively to shape constitutional law and public opinion, the two components of slavery’s future. The “Lemmon Case,” as the subsequent slave rescue and legal case was called, pursued both. The escape of Levi and James was one of many popular slave narratives that featured thrilling escapes and ruptured black families. The Lemmon (or Lemon) case offered an expanding nineteenth-century American reading public, fond of melodrama on stage and in print, a vast cast of characters, amazing coincidences, betrayals, reversals of fortune, family reunions, courage, and legal ironies. To call the events in the Lemmon case melodrama is not to diminish their contemporary power, but to enhance it. In its many aspects, the case offered spectators and readers courtroom drama and legal dueling, as well as a black family saga second to none in the literature of the 1850s. It also brought in a wide range of regional types, from Wall Street traders to Southern politicians, escaping slaves, and a middling mountain South family far out of its comfort zone.

As Levi saved his pay in Cleveland, Jonathan Lemon was preparing to move his family to Texas, leaving Bath County in October 1852. In addition to seven children, the Lemon entourage included eight young slaves, the oldest of whom was Emiline, the mother of two-year-old Amanda; Emiline’s teenage brothers, Lewis and Edward; and Emiline’s niece, Nancy. Nancy’s children, five-year old twin boys also named Lewis and Edward, and three-year old Ann completed the group. All had close kinship ties, and the older ones had been part of the distribution of Billy Douglas’s slaves in 1837.

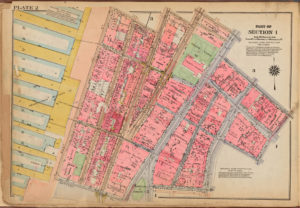

Seventeen days’ travel eastward toward the coast brought them to Richmond, the nearest port city to their inland home. The Lemons did not learn until they reached the capital city that there would be no ship to New Orleans for at least three weeks. Having neither the money nor the inclination to stay that long in Richmond, the seventeen people in the party traveled to Norfolk and took passage on the steamer City of Richmond for New York City, intending to transfer there to a ship bound for New Orleans (a rather circuitous route to Texas from Virginia). (A contemporary map of Virginia is viewable on the David Rumsey Map Collection site.)

Later, after the events transpired that would make him a household name across the country, Jonathan Lemon gave an account to a sympathetic New York newspaper of the Lemon family’s view of what took place when the ship docked in New York City on Friday, November 5. He had, he said, “no idea … that there would be any difficulty in going to New York with my slaves and proceeding thence to New Orleans.” Unworldly and uncertain of how to navigate the streets of the nation’s largest metropolis, Lemon placed much faith in the clerk on the City of Richmond, a Mr. Ashmead, who told him “that the law was in my favor in New York and was bound to protect me in the possession and property of my slaves.” Lemon was anxious to move his entire entourage to a New Orleans-bound ship. Offering to act on his behalf, Ashmead left the ship as soon as it docked, saying he would book passage to New Orleans for the Lemons and their slaves. But Ashmead returned saying that Lemon himself had to go to an address on South Street, where a man would help him (fig. 3).

Lemon went to South Street, where an unidentified man promised to transfer the entire party and their baggage to the Memphis, scheduled to sail for New Orleans the next day. Lemon returned to the City of Richmond with the booking agent:

And very soon two hacks came there, which he stated had been ordered by him, and into which myself, family and slaves got, under his direction, he saying to us that they were to convey us to the steamer Memphis. The hack then … drove round to his office in South Street.—Here I was told that I must pay our fare before being put on board of the Memphis. I then paid the amount, being $161. As soon as this money was paid, the hack drivers refused to take us to the steamer Memphis, but carried us, against our earnest protest, to a house at 3 Carlisle Street, dropped us down upon the sidewalk and drove off. It was now dark, and we being utter strangers in the city, were compelled to stay at that place till morning.

Early the next morning, a writ of habeas corpus was presented to Judge Elijah Paine of the New York Superior Court by Erastus D. Culver, a local attorney and abolitionist, saying that the black people now at 5 (sic) Carlisle Street were restrained of their liberty and ought to be freed based on the 1841 repeal of the “nine months law.” That law had been a provision in an 1817 act that had provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in New York State, and had permitted slaveholders to retain their slaves in New York if their stay was less than nine months. The repeal had not been tested since it was passed eleven years earlier. The writ of habeas corpus itself contained many errors that suggested no one had actually talked to the African American family at this point, but had only seen them at a distance. In it, Jonathan “Lemming” was described erroneously as a “negro trader.” But Judge Paine acted promptly, and the writ was served on Lemon that morning, with the black family taken into custody.

Although the stunned Jonathan Lemon was quick to see Mr. Ashmead as somehow responsible for his misfortunes, Nathan Lobam, the African American steward on the City of Richmond during the trip, claimed credit in an interview given almost a generation later. Lobam said that he approached the black family as the ship left Norfolk and learned their status. When asked if they wanted to be free, the women said yes, while the young boys were unsure. Once in New York City, the steward notified three members of an alliance of black and white abolitionists and Underground Railroad operatives in the city.

The petitioner in the case was Louis Napoleon, whom Lobam called “Napoleon Gibbs,” a black man working as a “polisher and finisher” in 1850 and sharing a house near the docks with Samuel Levingston, who had been born in South Carolina. Like Lobam, Levingston was an African American steward on steamboats, well placed to alert New York abolitionists to slaves in New York’s harbors.

That day, Saturday, November 6, the bewildered Lemons and the wary slave family appeared in Judge Paine’s court. The New York Journal of Commerce, persistently sympathetic to the Lemon family and to the South, described the scene: “Mr. Lemmon is past the middle age of life, and his dress and appearance bespeak him to be a man who has been and is still struggling with poverty. His wife, who, was she dressed in a fashionable attire, would be considered a splendid woman, also bears in her dress the same marks of comparative poverty as does her husband, but not in her manners, which are very lady-like. … they [the Lemons] naturally feel indignant at what seems to them an utter breach of the national compact.”

The courtroom confrontation provided high drama for newspaper readers. When the young black family was brought into court, the Lemons reacted in ways that said much about the economics and self-justifications of slavery:

Mr. Lemmon, when informed of the possible, if not probable, loss of his slaves, cried like a child. … Mrs. Lemmon went to where they were sitting, and in a tone and manner, highly excited, but more indicative of a mother to her children than a mistress to her slaves, thus addressed them—’Have I ever ill-treated you? Have you not drank from the same cup and eat from the same bowl with myself? Have I not taken the same care of your children as if they were my own? Did I not give up all I possessed in my native land, in order that you and I might go to another, where we could be more comfortable and happy? Did you ever refuse to come along with me, until you were prompted to do so?’

In their confusion and uncertainty, one of the young black women began to cry, and the other began to answer Mrs. Lemon, “when a white and a black abolitionist, in the same breath, told her to make no answer.”

The case was postponed until Tuesday, November 9, and when it was taken up “a large number of colored people of both sexes as well as others assembled” long before the appointed time. Those in the courtroom listened intently to arguments for and against the proposition that the enslaved family was now free.

At its core, the case revolved around the rights of slave owners when traveling through non-slave states. Did one state’s law supporting slavery supersede another state’s law prohibiting the institution? Was it constitutional for a slave owner to bring a slave into a free state for a week, but not for a month? Were, in other words, free states required to respect the right of slave ownership on a temporary basis when slave owners visited northern cities with their slaves? On these matters the United States Constitution was silent.

Henry D. Lapaugh and Henry L. Clinton, two young New York attorneys, represented the Lemons in Elijah Paine’s courtroom. Their pro-slavery position asserted that slavery was constitutionally protected, as evidenced by the three-fifths clause (Article 1, Section 2) regulating state representation in the House of Representatives based on a portion of a state’s slave population and by the clear provision of the fugitive slave clause (Article IV, Section 2), which required the return of slaves who had escaped from one state to another. Property rights in slaves, they argued, were as constitutionally protected as any other form of property, such as livestock or inanimate objects.

Lapaugh and Clinton also relied on the comity clauses of the Constitution, which address the respect one state voluntarily grants by enforcing the laws of another. One state’s consideration for another state’s authority is found in Article IV of the Constitution. Section 1 provides that “Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State,” while Section 2 stipulates that “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.” Since slavery was a property right authorized and protected by one state (in this case Virginia), Lapaugh and Clinton insisted that a non-slave state (in this case New York) should honor that right at least on a temporary basis.

The abolitionist attorneys for the state of New York, Erastus D. Culver and John Jay, argued a strong states’ rights position that each state had the right to allow or abolish slavery, and that the individual states alone possessed the right to determine the status of persons within their jurisdiction. Further, they maintained that the comity clauses of the Constitution did not require one state to afford rights to visitors that were not allowed to residents of that state. In other words, if New York residents were not allowed to own slaves, neither could visitors from a slave state.

Ultimately, Culver and Jay insisted that slavery was not a constitutionally protected property right. When the Constitution referenced slavery, it used the terms “person” or “persons” and never invoked the word “slaves.” The only obligation the Constitution afforded in this regard was that requiring the return of slaves “escaping” from one state to another. Importantly, the New York attorneys emphasized that the Lemmon case did not fall under the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution or the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law because the Lemon slaves were not fugitives—they had been taken by their owners into New York. They were more similar to the slave Somerset who had been purchased in Massachusetts and then taken to England, and who was determined free in 1772 because slavery was not protected by British law. While, of course, not binding in the United States, invoking the Somerset case distinguished the Lemon slaves from the fugitive slave provision of the Constitution, and served as a reminder to Judge Paine that the individual states alone had the right to permit or prohibit slavery.

On the next Saturday, Judge Paine delivered his opinion. Before another packed courtroom, the judge pronounced that “slavery can subsist only by the laws of the State,” and that it was well established that “a State may rightfully pass laws, if it chooses to do so, forbidding the entrance or bringing of slaves into its territory.” He concluded that the 1841 law of New York prohibiting slaves was “entirely free from any uncertainty,” and that “the eight colored persons mentioned in the writ, be discharged.” When Paine announced that the slaves would be freed, “much applause was exhibited.” The newly free family was conducted out by Louis Napoleon, placed in carriages and driven off, “amid great cheering and waving of handkerchiefs.”

Jonathan Lemon lamented “The result of the proceedings in court has deprived me of all my property, amounting at least to $5,000.” The New York Tribune commented bluntly on what this chain of events would mean for New York City business: “Here is a case which appeals directly to the gizzard of Cotton. If Mr. Lemmon is not compensated for his lost chattels, there can be no rational hope that New York will hereafter enjoy any portion of the carrying trade in slaves between the slave-breeding and slave-consuming states—a trade already considerable and certain to be largely increased by the annexation of Cuba.” The Tribune then urged its readers to contribute to a fund to recompense the Lemons for their monetary loss, suggesting that “Union-saving, Business, and Benevolence may all be combined in one operation …”

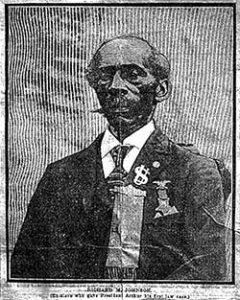

The Lemmon case, as it was already commonly known, was widely covered in New York City newspapers, with the national press reprinting those reports from the first day in Judge Paine’s court through the legal decision of the following week. In Cleveland, the local newspaper was read aloud by one of the workers at the American Hotel and, in one account, Levi, the runaway slave willed to Juliet’s sister Mary, and now living under the name Richard Johnson, exclaimed, “That’s my Aunt! That’s my sister!” The former slave also identified the older Lewis and Edward as his brothers, and the children as his cousins and nephews. Furthermore, he announced that his companion in flight to Canada, James Wright, was the husband of Nancy and the father of her children. Wiring the committee of support for the Lemon slaves, he sent his savings to the group and took a train to New York City.

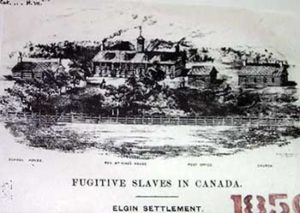

The most active members of the city’s abolitionist network had already taken charge of the emancipated group. Some eight hundred dollars was raised for their support and held for them by Judge John Jay. The Rev. James Pennington, once a fugitive from western Maryland, and his wife had taken them to Hartford, Connecticut, where Pennington was a pastor. There they were put in the care of black families for some weeks. In an early December meeting at the office of Lewis Tappan that included Richard Johnson (the former slave, Levi), Louis Napoleon/Napoleon Gibbs, Charles Bennet Ray of the New York State Vigilance Society, and Pennington, it was decided that Johnson would accompany his relatives from Hartford to Canada while plans were made to purchase one hundred acres for the group at the Elgin settlement at Buxton, Ontario, an experimental black communal settlement founded by a white minister, William King. Emiline, Nancy, the young boys and the children could not have been more fortunate in their destination (fig. 4). The Elgin settlement was probably the best site in Canada for fugitive slaves or free blacks from the United States in 1852. Fortunate in its leadership and organizational structure, it offered opportunities for farm ownership, industry, and education to its members, and survived longer than most such efforts in Canada or the United States. Richard Johnson was married to an Elgin woman by the Reverend King soon after the Lemon family arrived, and within a few years he moved the short distance to Michigan.

While New York’s abolitionists were making plans for the future of the newly emancipated family, the city’s pro-Southern business community was looking after their former owners. By November 23, $5,000 had been raised for Jonathan and Juliet Lemon by the “merchants and others” of New York City. Jonathan Lemon, on calmer reflection, admitted that he had been warned by the captain of the City of Richmond not to take his slaves ashore, and he absolved Ashmead, the ship’s clerk, of responsibility for his loss. The Lemons had already decided to return to Virginia. Their furniture, shipped earlier to New Orleans, was to be sent back to Virginia. For this money, the Lemons signed an indemnity saying that if, on appeal of the case, a higher court awarded them the slaves, the slaves would be manumitted. (They could not formally free their slaves then, as it would have invalidated the appeal of Judge Paine’s decision, which was making its way to the New York Supreme Court.) The following March, Jonathan Lemon paid $4,000 to Thomas and Susannah Lemon for a tract of land that they had recently inherited on the Cowpasture River in Botetourt County.

Had the legal dispute ended there, the Lemmon slave case would have become another minor event in the long-running antebellum legal and political battle over the rights of slave-owners. Judge Paine’s decision, however, did not go unchallenged. The slave-holding South reacted quickly with angry editorial comment in most southern papers, and many southern politicians were quick to attack the decision. Virginia newspapers followed the case closely and reported its every detail, especially as it concerned the Lemon family. They concurred in the southern assessment that if the United States Constitution permitted one state to deny property rights guaranteed in another state, the Constitution was useless. Georgia Governor Howell Cobb echoed much of the general thinking when he indignantly declared that “A denial of this comity is unheard of among civilized nations, and if deliberately and wantonly persisted in, would be just cause of war.” James B. D. De Bow, editor of the popular Southern periodical De Bow’s Review, labeled the manumitting of the Lemon slaves “subversive of the rights of the South in the Union.”

Somewhat more temperately, Virginia’s governor, Joseph Johnson, found Paine’s opinion to be “in conflict with the opinions and decisions of other distinguished jurists.” Because of its challenge to southern slave-owners, he determined it was “at war … with the spirit if not the letter of the Constitution itself.” On December 17, 1852, Johnson sent the New York Superior Court’s decision to the Virginia General Assembly with a request that the Assembly support the prosecution of an appeal to New York’s Supreme Court. Three months later, Virginia’s House of Delegates—with a unanimous vote—directed the state’s attorney general to prosecute the appeal.

So began an eight-year effort on the part of Virginia to challenge the right of a non-slaveholding state to ban slavery from its borders. While the national context for the Lemmon slave case changed slightly over its eight-year run through the New York State court system, it can best be understood as a piece of the ongoing and ever increasing sectional tension over the rightful place of the institution of slavery throughout the United States.

In spite of the very vocal opposition of abolitionists to the idea of slavery, there was limited public and political support for immediate abolition. Believing that the United States could only rid itself of slavery through a constitutional amendment, the vast majority of Northerners were content to leave the institution untouched where it already existed. And, as long as slavery remained within the confines of the fifteen slave states, controversy could generally be minimized. The issues that roiled the decade of the 1850s centered on the status of slavery outside of the South.

The famous Compromise of 1850 sowed the seeds of discontent over the future of slavery by offering something for both North and South, but satisfying neither. The North, for example, favored the admission of California to the union as a free state, but was disappointed that the remainder of the Mexican Cession was open to the possibility of slavery if its inhabitants so agreed. Southerners, by contrast, were angered over California statehood, because it upset the sectional balance in the United States Senate, and were distressed that the slave trade had been abolished from the nation’s capital. Abolitionists were pleased by the elimination of the trade in Washington, but were dismayed that slavery was itself still permitted there.

The component of the Compromise of 1850 that created the most unrest, however, was its Fugitive Slave Law, which was designed to clarify the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793. The revisions provided that federal marshals could help slave owners track down runaways, federal commissioners would be appointed to adjudicate fugitive slave cases, and the commissioners would be paid more if they returned the accused to slavery than if they determined the subject to be free. Northerners noisily objected to a provision that allowed them to be deputized by U.S. marshals in pursuit of runaway slaves. In essence, the new law allowed Northerners to be forced to become complicit in the return of fugitive slaves. In response, northern states began refining so-called Personal Liberty Laws designed to provide accused fugitive slaves a more equitable chance at acquittal. Personal Liberty Laws, in turn, were perceived by southern states as unconstitutional and “obnoxious.” It was within this charged political and legal environment that Judge Paine had rendered his decision.

For Governor Johnson and Virginia’s General Assembly, the Lemmon case presented a legal challenge not to states’ rights but to property rights. According to their interpretation of the Constitution, comity among the states required the free states to respect slave owners’ rights when they traveled north of the Mason-Dixon Line. With an ultimate goal of appealing the case to the United States Supreme Court, Virginia took a major and intentional step toward the nationalization of slavery. If the nation’s highest court determined that New York did not have the right to prohibit slaves to travel through the state with their owners, a precedent would be established that, while states had the right to establish or abolish slavery for their own residents, they did not have the right to unconditionally forbid its presence in their midst.

Virginia’s attempt to deny New York its “state right” to prohibit slavery within its borders was not lost on at least one contributor to the Richmond Enquirer. Only weeks after Judge Paine issued his judgment in New York City, an anonymous writer identifying himself only as “State Rights” submitted an article arguing that New York’s 1841 law banning slaves from the state was “not in conflict with the constitution of the United States.” While New York’s lack of comity may be “wanting in good fellowship,” the author was of the opinion “that each State has the right, and the sole right, to make laws relating to slavery.” The anonymous author of this letter to the editor reminded the Enquirer‘s readers that citizens are subject to local laws and that no constitutional principle allowed a citizen to “take the local law with him” to another state. “State Rights” was clearly out of step with Virginia’s political strategy, but saw that the states’ rights argument must remain consistent to have validity, even when it injured property rights in slaves.

Following Virginia’s appeal of Judge Paine’s decision to the New York Supreme Court, the case moved forward slowly. In Richmond, the General Assembly attended to the bureaucratic details of the appeal in an unhurried fashion, while Governor Johnson retained the services of New York attorney Henry D. Lapaugh. For its part, New York required Virginia to “execute bond for the costs,” which delayed scheduling the case before the New York Supreme Court. In December of 1855, Lapaugh optimistically reported that the case could be decided as early as March of 1856. He was mistaken.

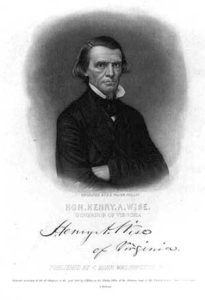

In January 1856, Henry A. Wise (fig. 5)—a passionate advocate for slave-holders’ interests—succeeded Johnson as governor of Virginia. Assuming office on January 1, 1856, Wise wasted no time in pursuing the Lemmon case. On February 14, he instructed his Attorney General to retain the services of New York Attorney Charles O’Conor to assist Lapaugh in prosecuting the suit. A prominent and successful lawyer, O’Conor eventually pursued the Lemmon case on behalf of Virginia through both the New York Supreme Court and finally the New York Court of Appeals, the highest state court in New York.

A keen observer of national events relating to slavery, Wise paid particular attention to the Dred Scott decision rendered by the U.S. Supreme Court on March 6, 1857. The case revolved around the question of whether the many years spent by the slave Dred Scott living in the free state of Illinois and the free territories of Wisconsin and Minnesota made him legally free. This case shared legal issues with the Lemmon case in that Scott was not a fugitive. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney declared that Scott was still a slave, and therefore ineligible to sue in a federal court. In addition, and equally important to pro-slavery advocates in the South, Taney claimed that property in slaves was specifically protected by the United States Constitution.

Governor Wise noted that the decision would “irritate and unite the Black Republican Demons of Discord” and predicted that in “our Virginia Lemmon case … we must fight it out with them, step by step, inch by inch …” He clearly expected unfavorable decisions in the New York court system. Indeed, only by losing at the state level could the case be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. With Chief Justice Taney controlling the court, and having just determined that the United States Constitution protected property in slaves, Wise was certain that the Lemmon case would be decided in Virginia’s favor if he could only get it out of New York State.

While Taney had recently ruled in Strader v. Graham (1850) that state courts possessed the final authority in determining the slave status of blacks, the Chief Justice, a Maryland native, was also becoming concerned over the growing national agitation over the issue of slavery and, along with most Southerners, was growing more defensive of the institution. He hoped that his decision in the Dred Scott case would bring an end to northern antislavery agitation. An aspect of the decision that is little appreciated today but was broadly repeated at the time came near its conclusion, as Taney reflected on property rights and their protection through the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment. Attempting to end the debate over whether owners of slaves were entitled to greater protection than owners of other forms of property, Taney insisted that “no word can be found in the Constitution which gives Congress a greater power over slave property, or which entitles property of that kind to less protection than property of any other description.” While the Lemmon case differed from the Scott case in that it was New York State and not the United States Congress abrogating slave rights, many observers (including Abraham Lincoln) believed Taney would rule against New York when the case was argued before the Supreme Court.

Complicating the political and judicial landscape were the editorial expressions of the Washington Union (the Buchanan Administration’s official mouthpiece), which represented the views of the executive branch in 1857. Symptomatic of the perceived movement toward the nationalization of slavery was its publication of an editorial proclaiming that slavery was, indeed, national, that slaves were recognized as property in the Constitution, and that the protection of that institution was the duty of every state. Appearing only seven months after Taney’s Dred Scott decision, the article proclaimed: “What is recognized as property by the Constitution of the United States, by a provision which applies equally to all the States, has an inalienable right to be protected in all the States.”

In a spirited congressional debate over the meaning of the Washington Union article and Virginia’s pursuit of the appeal, Senator Robert Toombs from Georgia in early 1858 attempted to argue that the slaveholding states had never asserted “the right to carry slaves into a sovereign State against its constitution.” To which charge, New York’s Senator Preston King offered the corrective that “the state of Virginia is now litigating in the courts the right of one of her citizens to hold slaves in the State of New York, the Lemmon case, well known through the country.” The Lemmon case was front-page news and clearly followed by editors and politicians alike.

In the state of political ferment following the Dred Scott decision, many Americans felt that the day would soon come when a Supreme Court decision would declare that individual states could not prohibit slavery within their borders. And there was a good chance that that Supreme Court decision could have been rendered on the Lemmon slave case.

The possibility that slavery would be made national by judicial action was a palpable reality by the end of the 1850s. Republicans had only to look at the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas Nebraska Act, the creation of an efficient slave code by the New Mexico territorial legislature, and the effort in California to create a “Territory of Colorado” in the southern portion of the state as evidence of an aggressive slave-power trend in the West. In addition, Taney’s opinion in the Dred Scott case that the Constitution protected property in slaves demonstrated that judicial support for slavery was in the ascendance, freedom was on the wane.

The “full faith and credit” and the “privileges and immunities” clauses (Article IV, Sections 1 & 2) would likely have provided sufficient basis for the Taney court to overturn the New York decisions. But the additional claim that property in slaves was protected in the Constitution and deserved “no less protection than property of any other description” placed the protection of “that kind of property” under the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment. If Taney was correct in believing that citizens could not be deprived of their property without due process of law, and that property in slaves was clearly protected in the Constitution, then slave-owners had the constitutional right to carry their slaves into the free states as well as the western territories unencumbered by local law. Or, so many Republicans believed. As Charles Sumner, the Republican Senator from Massachusetts, had earlier warned, the “Slave Oligarchy … contemplates not merely the political subjugation of the National Government, but the actual introduction of Slavery into the Free States.”

As expected, both the New York Supreme Court (December 1857) and the New York Court of Appeals (March 1860) ruled in favor of the state and against Virginia. O’Conor and Lapaugh logically argued the national import of the Constitution’s comity clauses and, after March 1857, insisted upon the relevance of the Dred Scott decision. After hearing Virginia’s arguments, however, the New York courts succinctly determined that “Comity does not require any state to extend any greater privilege to the citizens of another state than it grants to its own.”

Between 1852 and 1860, as the case worked its way through the New York court system, it grew in both notoriety and importance. Newspapers in New York and Virginia extensively covered developments in the case, and those stories were in turn widely reprinted. At the end of the decade, De Bow published a number of articles on the rising tide of sectionalism in the South. Submissions variously titled, “The Federal Constitution Formerly And Now,” “The Secession Of The South,” and “The South, In The Union Or Out Of It” all employed the Lemmon case to demonstrate that the constitutional rights of slave-owners were being egregiously eroded.

The nation followed the trials so avidly that shortly after New York’s Court of Appeals rendered its decision in March 1860, Horace Greeley and D. Appleton and Company both produced complete transcripts of all three judicial proceedings (fig. 6). Appleton’s advertisement pronounced that the Lemmon slave case was “one of the most significant and universally interesting trials that ever took place in this country.” Greeley sold his 146-page publication for twenty-five cents, five for one dollar, one dozen for two dollars, or 100 for sixteen dollars. So celebrated did the case become by 1860 that the first issue of Vanity Fair reflected on it without introduction or editorial explanation: “The South boasts of its lemon groves blooming and bearing fruit but once a year. The North has its Lemmons blooming perpetually, and shedding plentiful fruit into legal hands. We thought those Lemmons were squeezed long since, but find from the law reports, that they have taken a new ap-peal, and gone up for Lemmon-Aid.”

If the Lemmon case had reached the U.S. Supreme Court, an important step toward the nationalization of slavery could have been taken. In fact, however, Virginia did not appeal the decision of New York’s highest court. The reasons for this are not entirely clear, but a major factor seems to have been the election of John Letcher as Henry Wise’s successor as governor of the state. With John Randolph Tucker remaining as Attorney General under Letcher, as he had been under the last years of the Wise Administration, the decision seems to have been Letcher’s alone. A search of Letcher’s papers has not produced any justification for the decision. Letcher had worked hard in his campaign for the governorship to distance himself from antislavery remarks he had made a decade earlier, and perhaps he was engaging in a planned delay to see how the political landscape developed over the next several months in the presidential election of 1860.

As a Douglas Democrat and a conditional Unionist, he may have assumed that pushing the case to the Supreme Court would damage the Illinois senator’s chances as the party’s nominee in the fall. As it turned out, Douglas lost nationally in 1860, and polled a distant third in Virginia. Perhaps Letcher believed there was an outside chance that the Taney court would uphold New York’s claim to states’ rights, and he did not want to risk the consequences. Perhaps Letcher’s inaction in pursuing the case was merely the result of his longstanding political rivalry with Wise, whose faction of the Democratic Party in Virginia had vigorously opposed Letcher’s candidacy. In any event, Virginia did not pursue the case following the decision of New York’s Court of Appeals in the spring of 1860.

Nevertheless, as the nation moved toward war in 1860 and 1861, the Lemmon slave case figured prominently in southern states’ enumerations of their grievances against the North. In its Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union, adopted on Christmas Eve, 1860, South Carolina’s secessionist delegates listed their reasons for their fateful decision. Among the numerous complaints against the North for its continuous assaults upon the institution of slavery, South Carolina included the taking of the Lemon slaves. Georgia’s declaration of secession similarly complained that in “several of our confederate States a citizen cannot travel the highway with his servant who may voluntary accompany him, without being declared by law a felon and being subjected to infamous punishments.”

The Lemmon slave case echoed in other gatherings over the Secession Winter. James Seddon, Virginia’s delegate to the Washington Peace Conference (and former owner of the future White House of the Confederacy in Richmond) proposed several compromise measures. On February 26, 1861, Seddon offered a constitutional amendment in seven parts. Article four demonstrated that Seddon understood the implications of the New York law prohibiting the transportation of slaves into the state: “And the right of transit by the owners with their slaves in passing to or from one slaveholding State or Territory to another, between or through the non-slaveholding States and Territories, shall be protected.”

While Governor Letcher seemed uninterested in appealing the Lemmon case to the Taney court, the irrepressible Henry Wise was quite persistent in promoting the constitutional protection of slavery. As a delegate to Virginia’s secession convention in the winter of 1861, Wise proposed an amendment to the United States Constitution establishing “A full recognition of the rights of property in African slaves.” Failing initially to gain the approval of his fellow delegates, Wise persisted and on April 13—as Confederate guns were firing on Fort Sumter—he succeeded in writing into a proposed constitutional amendment that Virginia planned on delivering to the United States Congress a clause declaring that “the rights of property in them [slaves] shall be recognized and protected by the United States and other authorities, as rights to any other property are recognized and protected.” Of the dozens of compromise amendments proposed between Lincoln’s election and the attack on Fort Sumter, fully one half carried provisions to protect slaves while in transit with their owners or to nationalize slavery outright. Wise, like Taney, believed that the right of property in slaves ought to be explicitly embedded in the national charter, superseding any state law.

The long shadow of the Lemmon case also influenced the Confederate constitution-makers in Montgomery. Article IV, Section 2.1 reflected the lessons learned from the New York court system. To the “privileges and immunities” clause, the Confederate Constitution added, “and shall have the right of transit and sojourn in any State of this Confederacy, with their slaves and other property; and the right of property in said slaves shall not be thereby impaired.”

Throughout those years of legal challenges and political parrying, the Lemon family remained in Botetourt County, Virginia. By 1860, Jonathan Lemon had acquired five new slaves—a woman of forty and four small children, the oldest eight—property they once again lost, this time as a result of the Civil War. Two of the Lemon sons fought for the Confederacy, while Richard Johnson, once the slave Levi, enlisted to fight for the United States from his home in Michigan (fig. 7). A mini ball through his left elbow near Beaufort, South Carolina, in December 1864, left him disabled for the rest of his life. He died in Ashtabula, Ohio, in 1921.

In April 1881, Jonathan Lemon deeded his Botetourt County property to his wife Juliet and his children, giving as his reason “the fact that the … property was mainly acquired by the party of the first part [Jonathan Lemon] … by his marriage with the party of the second part [Juliet Lemon].” Jonathan Lemon died nine years later, in 1890, but Juliet lived until 1909. They are buried in separate cemeteries in the Shenandoah Valley (figs. 8, 9).

The Lemmon slave case illustrates both the legal debate over slavery that transfixed the country during the decade of the 1850s and the persuasive emotional power of slave narratives in that decade. One of the ironies of the ongoing legal case was the willingness of some Southerners to allow property rights to supersede states’ rights when the issue was the protection of slavery. If Governor Letcher had pursued the case, it would in all probability have become the next Dred Scott decision, as envisioned by Lincoln. Had Virginia pushed the case in 1860, as historian Paul Finkelman has observed, the “chances were good that some type of slavery would have been forced on the North.” Had Governor John Letcher been as hot-blooded as Governor Wise, the names Jonathan and Juliet Lemon would be as familiar to us today as the name Dred Scott.

Equally important, the case illustrates the extent to which the actions of enslaved and free blacks created much of the legal ferment and constitutional litigation that exacerbated the growing sectional conflict over the Constitution’s stance toward slavery and forced the courts to confront it. The escape to Canada, over several years, of at least four young black men from one family in Appalachian Virginia and the swift and competent dispatch to Canada of eight more of their relatives by New York abolitionists demonstrated for many slaveholders the necessity of a constitutional amendment to protect slavery in every state.

In the end, Virginia’s pursuit of a constitutional remedy was derailed by the election of Lincoln. The rhetoric and editorials that the Lemmon case provoked in the South had done much to make that region believe that Lincoln’s election meant the ultimate strangulation of slavery. The taking of the Lemon slaves contributed to the belief that the North was filled with abolitionists who, in their fanaticism, were willing to shamefully violate the basic tenets of the United States Constitution while, in the North, accounts of the escape, rescue, and reunion of the Lemon/Douglas slaves created sympathy for this and other enslaved families. The story of Levi touched much of the North, while the plight of the Lemons outraged the South. Levi, the runaway slave, and Jonathan Lemon, the backcountry slaveholder of modest means, acted for their own reasons, but both played central roles in creating a political drama that helped spark a constitutional crisis and contributed to a civil war.

Further Reading

While some aspects of the Lemon slave case have been explored and published, others have not. The best and most extensive source for the constitutional implications of the case can be found in Paul Finkelman, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1981). John D. Gordan III, “The Lemmon Slave Case” Newsletter of the Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York, Issue 4, 2006; and William H. Manz, “‘A Just Cause for War'”: New York’s Dred Scott Decision,” New York State Bar Journal (Nov./Dec. 2007) further add to the legal context. For background on black abolitionist New York City see Thomas J. Davis, “Napoleon v. Lemmon: Antebellum Black New Yorkers, Antislavery, and Law,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 33 (Jan. 2009): 27-46.

Horace Greeley’s N.Y. Court of Appeals Report of the Lemmon Slave Case: Containing Points and Arguments of Counsel on both Sides, and Opinions of all the Judges (New York, 1860) is the best contemporary account of all three court hearings.

Bath County, Virginia, public records, Civil War enlistment and pension files, American and Canadian census records, and contemporary newspapers were used extensively for the white Lemon and black Douglas/Wright/Johnson family.

The authors would like to thank Bryan Prince, historian of the African-American presence in Canada, and Shannon Prince, curator of Buxton National Historic Site and Museum in Buxton, Ontario, who generously shared their extensive research and their insights. Sarah Levine-Gronningsater shared her research on Louis Napoleon and the New York City abolitionists in the Lemmon case. Shirley Craft kindly gave us permission to use photographs of Juliet and Jonathan Lemon, and Jane Scott provided much needed legal advice. Jane Ailes provided access to contemporary newspaper accounts of the Lemmon Case and its immediate aftermath. (The family was “Lemon” in Virginia, but the case was “Lemmon” in New York and in the public prints. These separate spellings have been maintained.)

This article originally appeared in issue 14.1 (Fall, 2013).

Marie Tyler-McGraw is an independent public historian whose research specialties have been race and the upper South. Her most recent book is An African Republic: Black and White Virginians in the Making of Liberia (2007).

Dwight T. Pitcaithley is College Professor of History at New Mexico State University and an elected member of the American Antiquarian Society. From 1995 until 2005 he served as chief historian of the National Park Service