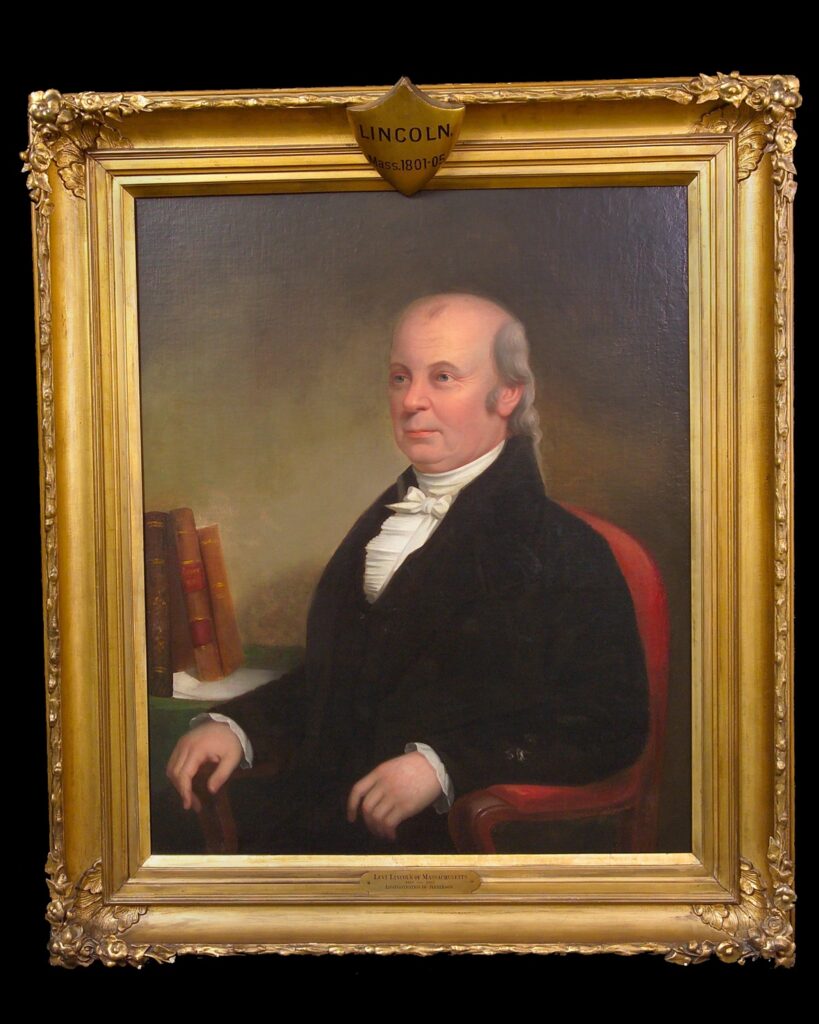

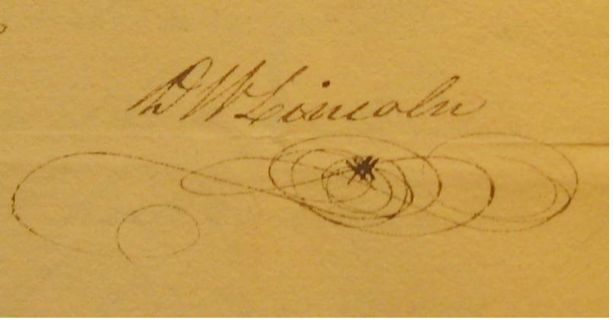

Being the son of an ambitious politician has never been easy. Just ask Charles Adams, William Franklin, or Hunter Biden. That was certainly true when Daniel Waldo Lincoln, son of Levi Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson’s first attorney general and in 1808 acting governor of Massachusetts, drank himself to death. Dying of an alcohol-related illness in the early nineteenth century was hardly uncommon. Nor was the stress that comes with shouldering a reputable family name. But documenting the struggle, failure, loneliness, and isolation, through his own discordant, entitled personality, was unusual. In over 250 private letters, Daniel Lincoln recorded it all, not for posterity or as a morality lesson for public edification, but as a plea for familial understanding that was not, to his great sadness, so forthcoming.

Levi Lincoln’s Wayward Son – Daniel Waldo Lincoln

Daniel’s preordained path as Republican steward began well enough, but it soon took a tragic detour.

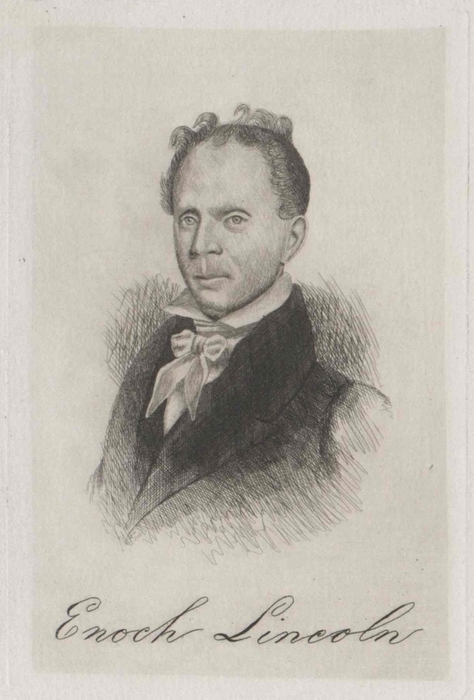

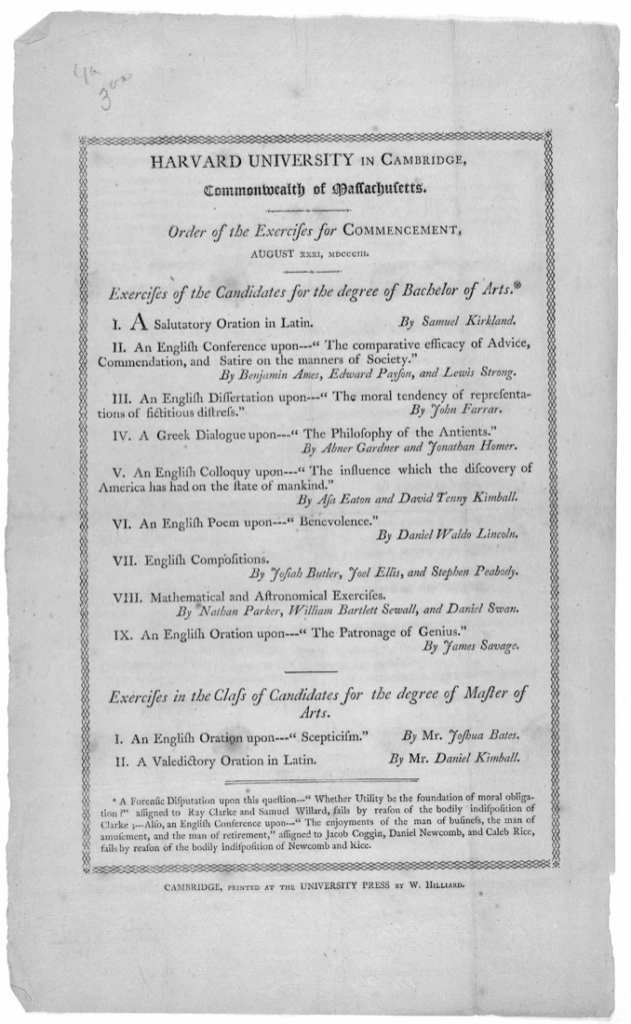

Of Levi Lincoln’s five sons, Levi II and Enoch would go on to become governors of Massachusetts and Maine respectively. Another son, John, became a sheriff and merchant in Worcester, and the youngest, William, became a lawyer and historian. His two daughters, Martha and Rebecca, married civic-minded lawyers. Indeed, before his life dissolved into unredeemable dissolution, Daniel Lincoln, the second son, had everything a man needed to make a good and distinguished life for himself. He had the Lincoln name, the education (Harvard Class of 1803), the occupation (lawyer), and the talent (orator and poet). But it wasn’t enough to save him from his addiction and the disastrous consequences that came with it.

The letters that make up Daniel’s story begin with his arrival at Harvard College in August 1801, forty miles from his beloved hometown of Worcester. Admitted as a junior, Daniel bypassed two years of hazing, complaining, and bonding with the other forty-three men in his class. His latecomer status to Harvard culture might have been but a minor handicap and socially negotiable, but Daniel was saddled with a different label that was harder to transcend—political outlier. Conservative Harvard had deep ties to the Federalist Party of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, the political nemeses of Levi Lincoln’s new boss, Thomas Jefferson. To make matters even stickier, just weeks before Daniel’s matriculation Levi had published a series of impenetrable essays entitled “A Farmer’s Letters” in which he excoriated Federalists, earning Levi the reputation as a “violent” Republican.

The fallout from Levi’s fevered attacks on Federalists cast Daniel into a netherworld of Harvard’s social untouchables. Other students avoided him. Social clubs either ignored or rejected him. He wrote to his mother that perfidious schoolmates who smiled at him had teeth like “whited tombstones.” He endured long, solitary walks pondering the place of self-interest in a country that both celebrated and feared it. He fantasized painful comeuppances to his enemies. “At college one may see all the subtle folly of the world & learn to fence with villains,” he observed to his brother. He wrote long dark poems about the ultimate leveler—death and graveyards. “Pow’r wealth and beauty are short-lived trust / Tis virtue only blossoms in the dust.” He missed the respect and recognition he got from his Worcester neighbors. “No one salutes me,” he moaned. Most of all he longed for his sweetheart and intended, Charlotte Caldwell.

By his second and final year at Harvard, Daniel had found a way to relieve his unhappiness, albeit temporarily. A classmate, William Sewall, who would go on to occupy a singularly undistinguished career as an attorney in Portland, Maine, introduced him to a more enticing life that featured “buxom girls with bosoms bear” and nectar from a “cheery vial.” Daniel was a changed man. Instead of bleakly attending coma-inducing recitations, Daniel accumulated fines for sleeping in chapel, ignoring deadlines, and leaving campus without permission. Even so, the Harvard government recognized his poetic talents and awarded him a coveted part in the 1803 commencement—to deliver a poem in English. They likely regretted their decision. The president, Joseph Willard, refused to sanction the piece, requested revisions, and threatened to withhold his diploma if Daniel refused to comply. But in a final nose-thumb to the school, Daniel delivered his poem “Benevolence,” a celebration of all things Jeffersonian in its original, unredacted form with this penultimate stanza:

The wretched sufferer they will never shun,

Whether he worship “twenty Gods or one:”

The rights of others never will refrain,

Who think with Watson, or agree with Paine.

Tis thus some phenix worthies erst have done.

Thus, too has Franklin, thus great Jefferson.

Their noble deeds elude the vulgar ken:

Sages in wisdom, as in feelings men.

Papists had sainted those of half their worth,

Applied their maxims as the tests of truth. . . .

The ode delighted Daniel’s father who immediately forwarded a copy to the third president.

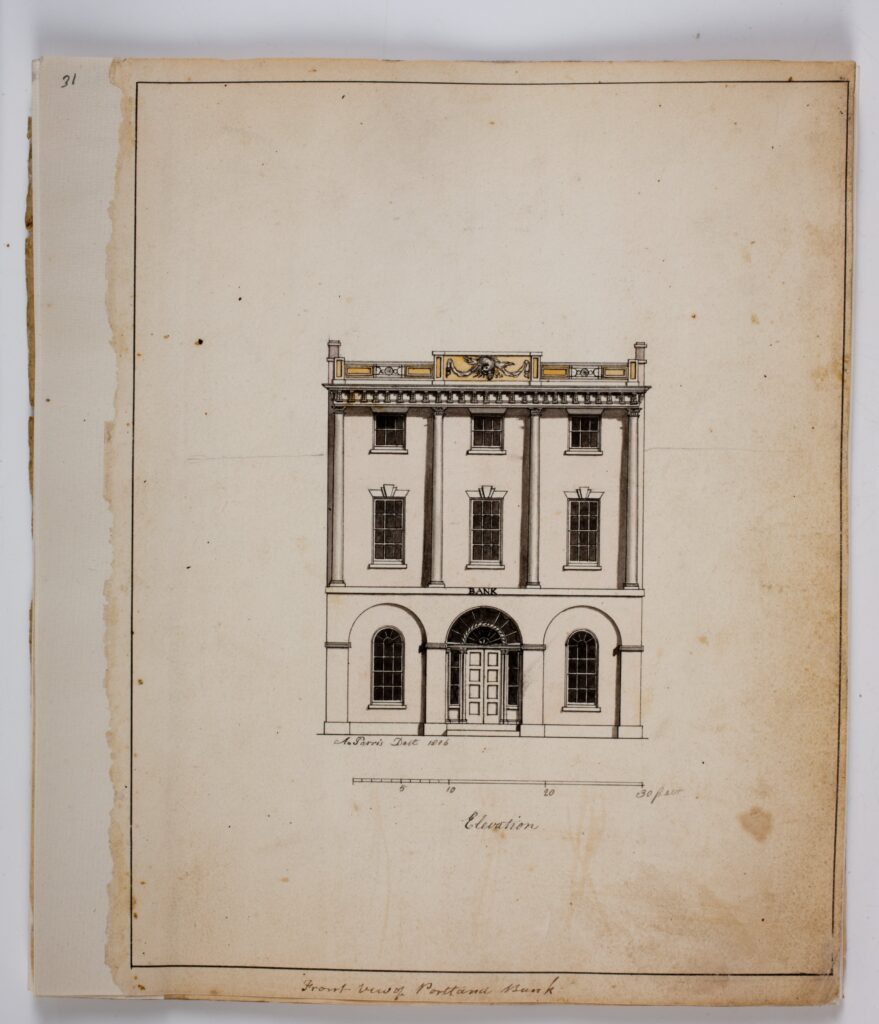

After Harvard and while studying law with Levi, Daniel’s preordained path as Republican steward began well enough, but it soon took a tragic detour. Disease took Charlotte Caldwell when she was only seventeen, devastating Daniel and pitching him into an alcoholic abyss so deep and so public that the only remedy to preserve the family’s honor was a soft banishment to Portland in the District of Maine. Chastened and repentant, he arrived there in August 1806. He passed the bar exam, tried to dry out by living with Quakers, set up an office in the new Portland Bank Building, and was given the post of Cumberland County Attorney by his father who had become the state’s lieutenant governor when James Sullivan was elected governor in 1807. Pleased to have a Lincoln heir in their midst, Portland Republicans sent him clients, invited him to speak at political events, and introduced him to local notables. He befriended other young elite Republicans, among them the son of Jefferson’s Secretary of War Henry A. S. Dearborn. “He appears to be a man of pretty talents & polished manners,” he reported to his brother Enoch of Dearborn. But Daniel’s praise was qualified. “His literary acquisitions are not extensive, & I fear his fondness for amusements will interdict professional eminence.” Not all the up-and-comers merited Daniel’s even conditional approbation. He scorned Portland’s parvenues who, in his view, were interested only in padding their wallets while ignoring their civic responsibilities. To him, this was self-interest dangerously run amok. “Nothing is good which is not profitable to them. They chide every wind of heaven which wafts not their cargoes to the port of destination. Their feelings are as callous as an Osnaburgh executioner,” he grumbled. Acting as his father’s eyes and ears on the ground, he dutifully reported the vagaries of Portland politics that became especially pitched during the Embargo of 1807 that sent Portland’s shippers into bankruptcy and into the arms of Federalists. Sullivan and Lincoln won reelection in 1808, but Daniel’s new home of Portland flipped Federalist.

In spite of all the political turbulence, Daniel fell in love again, this time with fifteen-year-old Mary Hodges. “Her friends discover in her, uncommon quickness of perception & veracity of thought,” he excitedly wrote to his sister. “She has a delicacy of mind & goodness of heart which cannot fail to attract and secure regard.” Here was Daniel’s path forward to a stable, respectable future. At last. But between periods of productive sobriety, there were also some blowout benders so discreditable that even the folks in Worcester got word of them. The bacchanals soon cost him his reputation and the affection of Mary Hodges. Embittered and disparaged, Daniel cast himself as a misunderstood victim of a brutal rumor mill and a coquette’s cruel machinations. It was everyone’s fault but his own. Down but not out, if a thorough rehabilitation couldn’t happen in Portland, he would try again in Boston. He was, after all, still a Lincoln and a Republican and with that pedigree he could make his way. His family thought otherwise. They viewed the move as a leap from the frying pan into to the fire. Boston would not welcome him. Daniel’s struggles would be more difficult and more public there. There would be pernicious rumors and mutterings. But Daniel went anyway. “I shall leave Portland & endeavor in the vicinity of my friends to revive their dormant, if not alienated & estranged regards,” he pronounced. If he couldn’t live up to his name, as he had so spectacularly failed to do, at least he could trade on it.

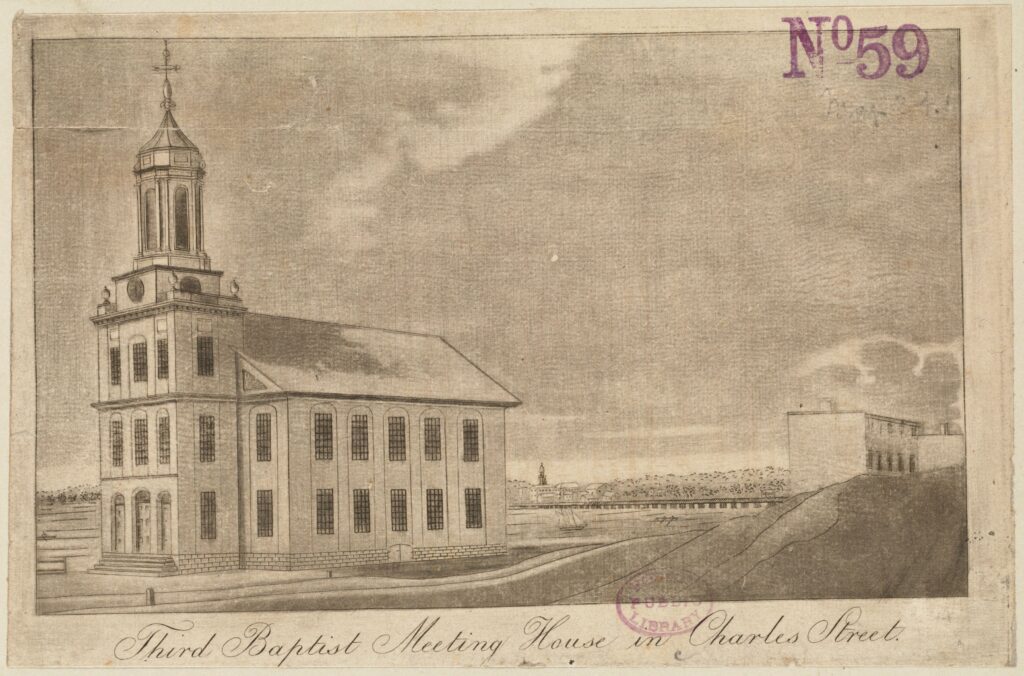

“My father has consented to his coming to Boston as the only means of saving him, believing that any place is better than Portland as he has yet some reputation to lose . . .” wrote Daniel’s brother John Lincoln in a heads-up letter to his Boston cousins. Clearly unhappy with his son’s decision, Levi was not yet ready to give up on Daniel entirely. He would do what he could to launch his son into Republican politics in the land of feral Federalism. Through Levi’s connections with the Bunker-Hill Association, the sponsors of Boston’s Republican July Fourth celebrations, Daniel was tapped to deliver the 1810 Independence Day oration. Occupying the front pews of the Third Baptist Church that day were John Adams, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Robert Treat Paine, and Elbridge Gerry among many others. It was an auspicious start but before too long his association with other young Republicans frayed and his law practice fizzled when his old Harvard classmates continued to shun him. “No professional acquaintance has favored me with a call since my arrival in town. Bestrew their little souls,” Daniel snarled. “Civility to me would not alienate their clients.” With the exception of some wealthy Waldo cousins who retained him in a Maine land claim dispute that they lost, only ordinary people, often without much money, sought his counsel. These common misfits and petty criminals were not the stuff of fame and fortune. Stymied, he looked to Governor Elbridge Gerry to deliver him a high-level patronage appointment that would rescue him. Eventually, after months of delay and foot-tapping, Gerry came through with a position suitable for the lawyer son of Levi Lincoln: judge advocate.

But by 1812, with the exception of his youngest brother William, then eleven years old, the family was through with Daniel’s bingeing, flirtations, and erratic ways. They thought it foolish when he once again uprooted himself and returned to Portland after Mary Hodges signaled she might be interested in renewing the relationship. “I should have become bankrupt in health, happiness, & estate in Boston, & have escaped an evil fate by removal hence,” he declared. Unfortunately for Daniel, the family in Worcester wasn’t buying it and correspondence faded to a trickle. He fired off indignant letters but received no response. His brothers ignored him, moving on and up in their political careers, not wishing to be burdened with a problem like Daniel. Their silence wounded him: “Am I so entirely exfamiliated that domestic concerns, of so interesting a nature, are to be known by me only through the medium of public prints? If such be the case, let me be assured of it, that I may return future letters (if perchance I should receive any) from former friends unopened.” Even Levi was tapped out. Citing his fading vision, Levi Lincoln had retired from public office in 1811, his influence over patronage now as dim as his eyesight. Only when Daniel became too sick and worn out to care for himself, after the relationship with Mary failed for a second time, did Enoch intervene and insist he go home to regroup and recover.

Daniel expected his convalescence to be brief, but months later he was still coughing, frail, and fatigued. “I consider it quite an equal chance that I never leave this town, that I find my settlement among those who have been,” he told Enoch. “I am incapable of the thought of business, a walk of one quarter of a mile is beyond my reach & a ride of a half-dozen miles length, should exhaust me to faintness.” Occasionally, however, he rallied. He was well enough in November 1814 to assist at the National Aegis when its editor, long-time friend Edward Bangs, left to defend Boston from a rumored British attack that never came during the War of 1812. “Our friend Danl W. Lincoln, has, to the astonishment of everyone, not only survived to this time but is regaining his health and strength so as to take exercise and employ the powers of his well-storied mind in the editorial department of the Aegis,” wrote Bangs. “Should God spare his life, I trust that a thorough reformation from his imprudencies, will prepare him for high usefulness in life and for the publick honours which he is qualified to obtain.” Bangs’ optimism was misplaced. In the early months of 1815, Daniel weakened, unable to leave his bed. He died in his sleep six weeks after his thirty-first birthday, on April 17, 1815. His fulsome death notice in the Aegis concluded with the forbidding phrase, Vitae summa brevis spem nos inebrare longam. Loosely translated means “Life is too short to spend it drunk.”

Would life had turned out better for Daniel Lincoln had he been born with a different name? Perhaps. Daniel certainly thought so. Without the privileges, without the expectations, without the advantages that shaped him, he would have had to find his own way and rely on his God-given talents and smarts to get there. He knew he failed his father’s expectations of what it meant to be a Lincoln and it pained him. Perhaps if alcoholism hadn’t claimed him when it did and made of him a “victim of intemperance” he would have used his gifts and privileges more beneficially for himself and everyone else. But he could not break free and when he crashed and burned, his name was all he had left. By then it was a façade, and he knew it. He lamented to his brother that he should never have been born a Lincoln. It was all a terrible blunder. “I believe our souls must have been strangely bewildered in their passage from heaven or they never could have strayed so far toward the North Pole and stopped amid a moral winter where selfishness locks up all social feeling and interest petrifies every pulse of the heart . . . Neither you nor I were intended to be Lincoln or Waldo,” he commented. “There have been mistakes & it is too late to correct them. Providence slept perhaps.”

Further Reading

This essay was based on the Daniel Waldo Lincoln papers at the American Antiquarian Society. Other sources include: Bangs Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society; Robert Hallowell Gardiner, Early Recollection of Robert Hallowell Gardiner (Hallowell, Maine: White & Horne, 1936); Mark Lender and James Kirby Martin, Drinking in America: A History (New York: The Free Press, 1987); Martin Junior Petroelje, “Levi Lincoln, Sr., Jeffersonian Republican of Massachusetts,” (Ph.D. diss., Michigan State University, 1969); William Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); William Willis, History of Portland from 1632 to 1864 with a Notice of Previous Settlements, Colonial Gains, And Changes of Government in Maine (Portland: Bailey & Noyes, 1865).

This article originally appeared in February 2023.

Rebecca M. Dresser, Ph.D., has been an adjunct professor of history at Hunter College and Marymount Manhattan College’s Bedford Hills College Program for incarcerated women. She is the author of The Life of Daniel Waldo Lincoln, 1784-1815: Letters from a Wayward Son (New York: Routledge Press, 2023).