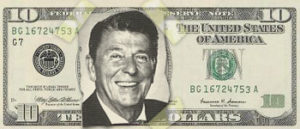

While the Founders of the United States have seen their reputations downgraded in some quarters over the past few decades, they have usually been able to count on the support of our leading political and cultural conservatives. When George Washington got left out of the National History Standards, when Thomas Jefferson’s DNA patterns were found in the wrong bloodstream, well-financed defenders rushed to the rescue. Pity poor Alexander Hamilton, then, for the Founders’ friends have forsaken him. While other major Founders have monuments on the National Mall and their faces carved into the sides of mountains, Hamilton’s one prominent memorial, his portrait on the ten-dollar bill, is under attack from the very same forces that have so often rallied behind his former colleagues. A well-connected conservative organization has begun a drive to put Ronald Reagan’s face on the ten-spot instead.

Hamilton has long been the least loved of the Founders. A treasury secretary rather than a president, as supporters of the Reagan tenner point out, his major accomplishments were in the arena of public finance rather than war or politics. And unlike his great rival Thomas Jefferson or fellow greenback illustration Benjamin Franklin, he did not leave behind a mass of quotable quotes suitable for use in everyday life and politics. Besides the Federalist essays, co-authored with Jefferson sidekick and historians’ darling James Madison, Hamilton’s major written legacy is a series of brilliant but highly technical reports on such matters as the public debt, banking, and manufacturing. As anyone who has assigned excerpts of them to an undergraduate class knows, those reports are more likely to inspire narcolepsy than patriotic reverence in the average modern reader.

Though Hamilton sought the status of national hero–“fame,” as he might have put it–his chosen route to that goal was “to plan and undertake extensive and arduous enterprises for the public benefit.” In other words, he sought fame as a lawgiver, statesman, and bureaucrat, rather than as a popular politician. Unlike the other figures emblazoned on our currency, and most other American leaders, Hamilton was notable for his lack of attention to personal popularity. He rarely minced words or obfuscated his views, and he showed a marked aversion to taking half measures in the pursuit of anything he considered a worthy goal. Popular unrest over taxes? The government “should appear like Hercules,” with troops, and show the punks who was boss. Wages too high for factories to be feasible? Hire women and children. The Constitution? A “frail and worthless fabric” that needed to remain as elastic as possible if it was to survive at all. Indeed, the record of Hamilton’s public career is a tissue of ideas and causes that were or became extremely unpopular: lenient treatment for Revolutionary Era Loyalists, life tenure for presidents and senators, the taxation of ordinary citizens, open subsidies to business corporations, the maintenance of a national debt, the restriction of free speech, and the reduction of the powers of the states, among others. To all of these other “PR” problems Hamilton added a sex scandal to which he, unlike Jefferson, freely and extensively confessed.

Hamilton’s poor public image befitted a political ideology that made little room for democracy and probably would have made little difference to the man himself. He retained the respect of the mercantile and legal elite whose opinions mattered to him, and his main objective in public life was to build a stable and prosperous national state that could govern effectively while thriving in a hostile, heavily armed world. At this Hamilton largely succeeded. But while Americans have always enjoyed feeling rich, powerful, and safe, they have also tended to chafe at the policies deemed necessary to make that so. Hamilton has had his political admirers over the years, but he never caught on with the culture the way that other Founders and political heroes did. Mount Vernon, Monticello, and Franklin Court became popular tourist destinations surrounded by impressive memorial infrastructures, while Hamilton’s home the Grange sits, sparsely furnished and little visited, literally tucked behind a church on a back street in the northern reaches of Manhattan. Builders of governments are hard to love.

Especially for those who hate government. The source of the effort to remove Hamilton from our wallets is the Ronald Reagan Legacy Project, the same people who got Reagan’s name added to Washington National Airport and Florida’s major turnpike. An arm of the anti-tax group Americans for Tax Reform, the Legacy Project’s self-described mission is to name “significant public landmarks” after Reagan in each of the nation’s fifty states and three thousand counties, “as well as in formerly communist countries across the world.” Alas, the drive to put a Gipper monument in every county seems to be going slowly. There are some schools, bridges, streets, parks, and museums in the Illinois towns where Reagan grew up, and in California where he was governor. But elsewhere the memorial pickings are slim: a building at a Mississippi Sheriffs’ Boys and Girls Ranch and an historical marker in Iowa are important enough triumphs to list on the “Legacy Project Website.” Also highly touted is the possibility that a new high school in Fishers, Indiana, set to open in 2006, might bear the Reagan name.

The campaign has been much more successful with sites directly controlled by the Big Government in Washington, where the inside-the-Beltway conservative activists who care most deeply about the issue are much more influential, despite their erstwhile commitment to shrinking government. The project’s board of advisors includes Attorney General John Ashcroft and numerous Republican congressional leaders, including House Majority Leader Dick Armey and Majority Whip Tom DeLay. Among the successful namings and renamings they count not only the Washington airport, but also the nuclear aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan, the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site in the Marshall Islands, and a proposed Reagan memorial on the National Mall.

The head of both the ATR and its Reagan Legacy Project is lobbyist and “issues management strategist” Grover G. Norquist. An ally of Newt Gingrich, Norquist spent the past decade coordinating what he calls a “Leave-Us-Alone Coalition” of right-wing groups, including “property owners, anti-tax activists, gun owners, home- and private-schoolers, small business owners, religious conservatives, and libertarians.” Wielding much of his influence through Wednesday-morning strategy sessions at the ATR offices to which representatives of various conservative causes are invited, Norquist has been given credit for some of the signal conservative policy campaigns of the 1990s, including the scuttling of the Clinton health plan, the 1994 Republican takeover of Congress, and the numerous state-level drives for “paycheck protection” laws (bans on the automatic withholding of union dues) that have now percolated up into the Bush administration’s agenda. Norquist’s group is also responsible for the “Taxpayer Protection Pledge” (against raising taxes for any purpose or under any circumstances) that most Republican politicians have routinely signed since George H. W. Bush failed to read his own lips. While Grover Norquist is not a household name, inside Washington he is known as one of the most influential of the conservative activists who currently set the terms of our political debates. Some conservatives regard him as nothing less than a hidden prime mover of modern history. His pal Newt Gingrich hails Norquist as “the most innovative, creative, courageous and entrepreneurial leader of the anti-tax efforts and of conservative grassroots activism in America . . . He has truly made a difference and truly changed American history.” The man himself boasts of “saving” the country from the outbreak of–quel horreur!–“social democracy” represented by a national health plan. Like Richard Nixon but without the charm or social conscience, Norquist regards all government programs as nothing more than attempts to buy votes. And, like Charlton Heston and the Militia of Montana, he regards almost any effort to regulate or tax anything as a horrific infringement of human freedom. Norquist looks forward to cutting all forms of government in half over the next twenty-five years. This will be tough, he concedes. But if the full agenda of extreme economic conservatives were enacted–“if you privatize Social Security, if you voucherize education, if you sell the $270 billion worth of airports and wastewater treatment plants, eliminate welfare, and so on”–then it could be done.

On the surface, it is easy to see why movement conservatives like Norquist would be repelled by Alexander Hamilton, whose great concern was to firmly establish the government that Norquist hates so much, who virtually introduced national taxation in America, and who was not afraid to use force to collect the taxes that were laid. If the Whiskey Rebellion were held today, Norquist (an NRA “life member” and director) would certainly be out shooting up the revenue collector’s house, not marching west with Hamilton and Washington’s army. Still, the Reagan Legacy Project has thus far not cited any substantive objections to Hamilton, other than to state the obvious truths that he was not a president and that his political party no longer has any seats in Congress. (Washington and Franklin, take note.)

Yet there is clearly something deeper going here. A Republican-led drive to erase Hamilton from the national memory represents a significant shift in American conservatives’ narrative of their own history, a tale in which Hamilton has long played a prominent role. Though Aaron Burr slew Hamilton decades before the modern GOP emerged, Hamilton’s relatively few political fans have almost always been Republicans. It seems to have been the Lincoln administration that first put Hamilton’s face on United States currency, and the Coolidge administration that granted him the prominent location on the ten. Theodore Roosevelt was one of Hamilton’s few vocal presidential supporters. In more recent times, such conservative writers as William Bennett, Karl-Friedrich Walling, and the National Review’s Richard Brookhiser have written admiringly about Hamilton.

More importantly, there are some substantive reasons for modern conservatives to admire the first treasury secretary. Hamilton was to some degree the original theorist of trickle-down economics, taking the view that the creation of large fortunes and intensive development were ultimately good for the nation, however unequally the benefits might be distributed. His financial system quite frankly aimed to lock the government into a tight embrace with its creditors and gave special benefits to business interests. The Bank of the United States was not the Federal Reserve but a private, profit-making corporation that got to use the government’s tax receipts as its capital. From the excise tax to the “funding” at face value of a devalued debt that speculators had bought up from cash-strapped citizens, the financial system amounted to a significant transfer of wealth to an entrepreneurial elite that Hamilton hoped would both support the new government (because they were profiting by it) and invest their profits in developing the still largely rural republic.

Hamilton is the legitimate ancestor of modern conservatives on other counts as well. One recent study, Walling’s Republican Empire, depicts Hamilton as the original Cold Warrior, an “American Churchill” whose vigilance and calls for military preparedness saved America from French aggression just as later conservative leaders saved the world from Nazism and communism. Hamilton can also be considered the inventor of the organized religious right in America. In the presidential campaigns of 1796, 1800, and 1804, Hamilton’s Federalists, assisted by many of the old-line clergy, stoked the fears of pious New Englanders regarding Jefferson’s liberal religious views and personal libertinism. Hamilton suggested taking these efforts a step further and creating a network of Christian Constitutional Societies that would instruct devout citizens in how to follow the inevitably Federalist dictates of their faith. In all of these ways, then, Hamilton offers a highly usable past to twenty-first century conservatives.

Why, then, the drive to remove him from our wallets? The excision of Hamilton from the story of American conservatism meets a critical ideological need for antigovernment extremists of Grover Norquist’s ilk. A Hamilton in the national pantheon presents an uncomfortable contradiction for these people. Here was a great American white male, a Founding Father no less, of impeccably conservative, pro-business instincts and beliefs, who nonetheless recognized that there were public goods that only governments could accomplish. Hamilton would have found the simplistic opposition that the current Republican right depends upon–an opposition between government activity of any kind on the one hand and human liberty on the other–to be manifestly absurd. Hamilton understood that government exists to protect liberty, a fact that today’s conservatives prefer to sidestep–except, of course, when liberty is threatened in some far away and potentially profitable place, such as a Kuwaiti oil field.

If Hamilton was too soft on government to suit today’s conservative tastes, he was also far too honest in announcing his purposes, having not yet grasped the essential strategic insight of modern reactionary politics. One of the most significant changes in the Republican party since the 1950s, a change that came in with Richard Nixon and Joe McCarthy and helped usher both Nixon and Ronald Reagan into the White House, was its embrace of an aggressive but basically dishonest populist rhetoric. While the party’s financial backers and preferred policies changed relatively little, its leaders began shaking their fists at evil liberal “elites” in the name of the common man. Yet even Nixon felt the need to give his “silent majority” rhetoric some substantive backing by courting labor leaders and continuing or expanding most New Deal and Great Society programs. In the 1980s and 90s, the Reagans, Bushes, and Norquists came to believe such substantive compromises were no longer necessary: that even policies baldly aimed at redistributing wealth away from ordinary Americans, or making their jobs less secure, or crippling the government services they depended on, could be sold with populist slogans about paycheck protection, death taxes, and tax cuts for “working Americans”–slogans sprinkled liberally throughout the ATR Website in justification of the new Bush administration’s plutocrat-oriented tax proposals. This kind of political inversion is the real legacy that Norquist means to memorialize on the Reagan ten-dollar bill.

Like his friend Newt, Norquist is one of those so-called conservatives who talks, and may actually believe, that he is in fact some kind of social revolutionary. While there is reason to doubt that a former U.S. Chamber of Commerce employee really poses much threat to the social order, Norquist’s revolutionary self-image does seem accurate in at least one sense: he and his friends display a distinctly Soviet penchant for rewriting history to suit the present regime’s needs. By forcibly making Reagan into the towering figure of modern American history, today’s “movement” is trying to install a grandiose view of its own importance and heroism in our collective memory, while they have the votes in Congress and a friend in the White House. The proposed Reagan for Hamilton switch may not be the most important of these efforts, but it manages to seem both chilling and stupid, like the famous doctored images of Stalin conferring with Lenin.

Though the idea of adding Reagan to Mount Rushmore has been rejected, there seems to be a serious intention of transforming Reagan into some kind of honorary Founding Father. These are exactly the terms in which one Legacy Project supporter justified a Reagan-naming proposal. “At a time when the names of our Founders are being stripped from schools in other areas of the nation,” said an Indiana conservative, with no thought for poor Hamilton, “let’s rekindle the spirit that respects those figures from our past who helped give our futures promise.” Perhaps next the Gipper can be painted over John Adams in Trumbull’s Signing of the Declaration on the Capitol walls.

Further Reading:

E. J. Dionne’s Washington Post column for March 23, 2001, commented on the Reagan Legacy Project’s designs to rewrite history and suggested the Soviet comparison elaborated on above. Dionne called Norquist “the Lenin of the contemporary right.” I would pick Stalin or Trotsky myself.

An alarming interview with Grover Norquist from the libertarian magazine Reason is the source of several of the quotations above and is available here.

Conservative appreciations of Hamilton can be found in Karl-Friedrich Walling, Republican Empire: Alexander Hamilton on War and Free Government (Lawrence, Kans., 1999); Richard Brookhiser, Alexander Hamilton, American (New York, 1999); and William J. Bennett, Our Sacred Honor: Words of Advice from the Founders in Stories, Letters, Poems, and Speeches (New York, 1997).

The whole history of currency portraits can be learned from “Dawn’s Virtual Currency Collection,” where U.S. paper money can be browsed by portrait. Who knew De Witt Clinton, Thomas Hart Benton, Albert Gallatin, Silas Wright, Daniel Manning (duh! treasury secretary under Cleveland!), and a bunch of generals and admirals were all once the faces of legal tender? Dawn’s site is light on analysis, but a distinct pattern of partisan portrait selection emerges.

For additional, late-breaking comments and information on Hamilton and the Gipper, including a belated response from the Reagan Legacy Project itself, click here.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.3 (March, 2001).