When three English ships sailed into the Chesapeake Bay in late April 1607, they did so amid a soundscape of groaning masts and spars, crew members heaving on the capstan and furling the sails, and the strains of song and instrumental music. This simple claim reminds us that music provided one of the most significant yet underreported dimensions among the first encounters between indigenous and invading cultures as the English established a permanent presence on the western shores of the North Atlantic Ocean. The 2010 commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the founding of Hampton, Virginia, the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in North America, was also the 400th anniversary of the dispossession of the Kikotan people, routed in a military attack enabled by a musical ruse.

What might seem like a novel stratagem for battle was actually not unusual. Historical texts reveal that music was a vital military tool on both sides of the Atlantic, and much more: a key element of ritual; an indispensable aid to labor; a method for building and maintaining morale; and above all, an integral part of communication. The most elemental of instruments—the human body—was the most common. People clapped their hands, stamped their feet, or, especially, raised their voices. During the early-modern period in virtually all cultures around the globe, wherever instrumentation was wanted or needed, a striking variety was available, to serve a surprising number of functions and employ virtually everyone in a troop, crew, or community in some sort of music production. In a world where not everyone could read or even speak a common language, everyone could make music, and did.

It is one thing to recognize this musical world, another to explore it. Early-modern methods of recording sound—text, musical notation, and oral traditions—leave a compromised record that can only be accessed intellectually and theoretically, rather than experienced sensually through ears and eyes. Orality poses problems of its own. Even the most sophisticated mnemonic devices can be suspect, in terms of whether they tell the history of the people involved in the story, or in its re-telling. Further complicating the evidentiary problem for these earliest Anglo-Atlantic musical histories is that the surviving record was written largely by only one party involved in this cultural contact—the English. Even the historical evidence that does exist presents a great challenge to musical inquiry, perhaps because so little was said about music in primary documents of the period, leading relatively few historians to write about it as more than a garnish to the main courses of historical inquiry.

Yet even this limited historical record suggests a shared understanding and utility of music across cultures. The sources—primarily travel narratives written by English explorers—frequently reference the music, song, dance, and instrumentation used by English and Natives alike, offering tantalizing hints about the music’s reception by both parties. One of the richest sources documenting such encounters involving the English prior to 1600 isPrincipall Navigations, English cleric and geographer Richard Hakluyt’s masterwork, published in editions in 1589 and 1599-1600. The editions fulfilled what historian Peter Mancall called the author’s “promise” to promote English settlement around the world, a commitment that drove Hakluyt’s collection and publication of widely read travel narratives. No less a commentator than author and courtier Sir Philip Sidney (to whom Hakluyt dedicated his 1582 Divers Voyages) once employed a musical metaphor to praise his work: “Mr. Hakluyt hath served for a very good trumpet.” Hakluyt’s personal investment in English exploration culminated in his participation in the formation of the Virginia Company, promoter of the expedition that, in 1607, led to the first recorded Anglo-Kikotan contact.

Principall Navigations became a “bible” for transatlantic voyagers of the seventeenth century, chronicling English expeditions allegedly reaching back to the dawn of time, undertaken to every corner of the known world. Martin Frobisher, Humphrey Gilbert, and John Davis all reported on the usefulness of music as they sought to stake a claim for England in the Western Hemisphere. Hakluyt’s accounts gave copious evidence of music as a means of communication, a tool of warfare, an aid to commerce, a religious practice, a form of entertainment, and a means of building community between Europeans and Natives alike. Elements included trumpets, drums, timbrels, barrel organs, and much singing and dancing. Morris dancing, a common English village dance practice, was specifically mentioned in the provisioning of Gilbert’s 1583 final voyage, to the North American Atlantic coast, as an activity to be executed “for solace of our people, and allurement of the Savages.” Central among the instruments used on such expeditions were trumpets, useful whether to announce the beginning of a conquest—as when Gilbert sounded a trumpet to formalize English “regency” over Newfoundland—or the end, as in the case of the Roanoke colony, when, in 1589, John White returned looking for his family and friends: “we sounded a Trumpet, but no answer could we heare.”

Hakluyt even reported an example of musical subterfuge that took place during Frobisher’s first voyage, undertaken in 1576 to search for a Northwest Passage. Frobisher’s scribe, George Best, told how his captain wanted to capture a Native person to take home as a “token,” and “knowing wel how they greatly delighted in our toyes, and specially in belles, he rang a prety lowbell” to lure a potential captive to the side of the ship. Several attempts were unsuccessful until, “to make them more greedy of the matter he rang a louder bell.” The bait worked, and the captive would eventually pay for it with his life, reaching England but dying “of cold which he had taken at sea.”

That Davis considered music to be essential to his mission is clear; he allotted four of twenty-three berths on his flagship to musicians. Even John Smith of Jamestown, who rarely mentioned the ways music would have been used in the Virginia colony and did not include a single musical instrument on his list of things to take to the Americas, nevertheless documented the presence of at least one working musician: among the handful of men in the 1607 crew identified as having a specific skill is “Nic. Scot, drum.” This is not to say that Smith never mentioned music—on the contrary, several of his books demonstrated its importance to a variety of functions, particularly military uses. Smith’s True Travels, Adventures, and Observations included his description of a European coupling of the musical and martial at the battle of Rottenton, begun “with a generall shout, all their Ensignes displaying, Drummes beating, Trumpets and Howboyes [oboes] sounding.” Similarly, in A Sea Grammar, Smith described how the pursuit of an enemy ship would begin by hailing it “with a noise of trumpets,” and conclude with the “sound[ing of] Drums and Trumpets,” after which, the officers would “board [the] other ship … with the Trumpets sounding.”

Nor was all shipboard music instrumental. Smith described in the Grammar how the “Gang of men” who rowed the smaller boats would “saies Amends, one and all, Vea, vea, vea, vea, vea, that is, they pull all strongly together,” a style suggesting the familiar work song of the sea, the shanty. The Grammar also contained another example of vocal music, in which crew members would begin and end the evening watch with a psalm and a prayer.

Though Smith mentioned the presence of drums and drumming, only the trumpeting that figured so centrally in Hakluyt’s accounts also appeared in Smith’s texts with a formal role for its practitioners among a ship’s “Company,” or crew. An earlier version of the Grammar entitled An Accidence for the Sea indicated that the trumpeter was compensated at the same rate as the boatswain, marshalls, and quartermasters, and at a higher rate than the corporal, “chyrurgion” (surgeon), steward, cook, coxswain, the sailors, and the “boys.” The Grammar indicated roles for both a “Trumpeter” and a “Trump. Mate,” with the former valued at the same rate as the surgeon, gunner, boatswain, and carpenter. Smith provided this description of duties and compensation:

The Trumpeter is alwayes to attend the Captaines command, and to sound either at his going a shore, or comming aboord, at the entertainment of strangers, also when you hale a ship, when you charge, boord, or enter; and the poope is his place to stand or sit upon, if there bee a noise, they are to attend him, if there be not, every one hee doth teach to beare a part, the Captaine is to incourage him, by increasing his shares, or pay, and give the master Trumpeter a reward.

Folklorist Roger D. Abrahams has argued that English parading traditions such as those described here originally grew from medieval practices “to display and enhance the power of the nobility or the monarchy.” Abrahams cited an early example of this at Plymouth Plantation in which Miles Standish “would not leave the encampment without arraying in parade his six or seven soldiers led by a drummer and a horn-blower.” An earlier, similar example can be found in Virginia, according to an account in True Relations. During a meeting between John Smith and Wahunsonacock, the powerful chief most often referred to by Natives and English alike as “Powhatan,” trumpeting preceded the arrival of Captain Christopher Newport, producing a sound that Philip Barbour observed, in his edition of Smith’s Complete Works, would have been “surely more strident than any sound the most stout-lunged Indian warrior could make.” (Smith also identified “Powhatan” as the name of a river, a nation, a country, and at one point, a “place” with forty fighting men.) Beyond a question of volume, though, Newport’s procession would have been intended as an impressive display of personal or monarchal power, or both.

In contrast to his other books (or, for that matter, the relatively rich record of significant musical functionality aboard early-modern Atlantic expeditions reported by Hakluyt), Smith’s Generall Historie of Virginia, first published in 1624 and often relying on earlier accounts by others, revealed very little about the English use of music in the early days of encounter in the Chesapeake. But the Historie did contribute significantly to the otherwise elusive musical history of the Powhatan peoples, a deficit due to what some ethnomusicologists have referred to as a “shattering” of musical traditions among southeastern Native tribes following the first decades of contact with Europeans. In the same way he documented the names of rivers, tribes, flora, and fauna, Smith (or his scribe) faithfully recorded evidence of Native music used for communication, rituals, entertainment, warfare, and work. Just as the European musical salvos reported by Smith were designed to impress their auditors, so did Native music produce an impressive, even “fearful” sound—the “terrible howling” also remarked upon by William Strachey. Still, the Historie demonstrated an explicit understanding of the ability and intent of certain types of this “savage” music to “delight” rather than “affright” the listener.

The Historie used European terms to describe Native instrumentation. The description of an aerophone made of “a thicke Cane, on which they pipe as on a Recorder” suggests both visual and tonal similarities between the English and Native instruments named. In the case of “their chiefe instruments … Rattles made of small gourds, or Pumpeons shels,” the author assigned the voice-parts of “Base, Tenor, Countertenor, Meane, and Treble,” terminology reflecting a European understanding of the tones the rattles produced—low to high, respectively, with larger gourds producing deeper tones. This attempt to make sense of a musical relationship across cultures by imposing a European framework would have made the objects more familiar (and perhaps less “savage”) to the author and his readers alike, part of what Karen Ordahl Kupperman has described as a tendency on the part of both sides to see the other culture “in terms of traditional categories …. to fit these other people and their trappings into their own sense of the normal.”

Reading the narratives with new ears, then, shows the development of a musical dialogue evolving right from the moment that English ships arrived at the mouth of the river that Natives called “Powhatan,” and which we know today by the name imposed by the English to the river and their settlement alike: James. Three very different periods of musical encounter mirror the moments in which they took place: introduction, cooperation, and destruction.

In April 1607, as the English ships Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery prepared to enter the Powhatan River, they encountered a smaller river flowing north that shared a name with its inhabitants, the Kikotans. It was “a convenient harbour for Fisher boats … that so turneth it selfe into Bayes and Creekes, it makes that place very pleasant to inhabit.” The Kikotans themselves were relative newcomers, having been sent by Powhatan to remove another Native group some fifteen years earlier. A decades-long continental demographic crisis followed the arrival of Europeans, and David S. Jones has argued this may have been due to multiple factors, including disease but also “poverty, social stress, and environmental vulnerability.” For the survivors, this was a time of consolidation and intense intertribal conflict, and Kupperman has suggested the English contingent’s potential as allies in these struggles may have been the reason Powhatan allowed the English to survive during those first fragile years of settlement.

Smith did not record how the English might have introduced themselves musically to the Kikotans, though his examples in True Travels, the Grammar, and the Accidence suggest that trumpets and drums might well have announced their arrival. But the journal of George Percy provided a much clearer picture of how the Kikotans introduced themselves.

As the youngest son of the ninth earl of Northumberland, Percy had the highest social status among the English, though as a lieutenant he was subordinate in military rank to Smith. According to Percy, the Kikotans performed music as part of a spiritual ceremony characterized by “a doleful noise,” and in rituals of hospitality inviting the English to share a meal with their hosts, amid “singing … dancing … shouting, howling, and stamping against the ground, with many antic tricks and faces.” In deconstructing English assumptions that such music was “savage,” one can perceive a musical aesthetic that was rhythmic, energetic, and participatory—characteristics also found in European music. This first encounter created for the participants an aural record of each other’s cultures and would have affected their evolving cross-cultural sensory understanding as music continued to play a role in subsequent encounters.

Given the nearness of the Kikotan village to Jamestown and its strategic location at the first inland river off the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, perhaps Smith was relieved to estimate that “besides their women & children, [they] have not past 20. fighting men.” The musical component of any potential fighting became immediately apparent when, shortly after their initial encounter, Smith returned to Kikotan with a half-dozen crew in a small vessel called a “shallop” to trade for food, only to be greeted by “scorn” and “derision.” Smith responded with gunfire. Hostilities quickly escalated, as “Sixtie or seaventie” painted “Salvages” emerged from beyond the tree line, charging while “singing and dauncing out of the woods.” Smith’s men answered by shooting the Kikotans’ religious idol, then suing for terms. The result: more singing and dancing, but this time “in signe of friendship,” as the two sides traded “Beads, Copper, and Hatchets” for “Venison, Turkies, wild foule, [and] bread.”

Several times in 1608, the Kikotans provided refuge to the English during the latter group’s explorations of the Chesapeake, encouraged by a belief that Smith and his crew had been, or would be, “at warres” with the Kikotans’ enemies to the north, the Massawomeks. On one of these occasions, they sheltered an injured Smith after he had suffered what he supposed to have been a near-deadly encounter with a hog-nosed ray at a place still known as “Stingray Point”; another time, when the wind delayed the English for “two or three dayes … the King feasted us with much mirth.” But perhaps the most poignant encounter documented during this period of relative cooperation took place the week following Christmas 1608, when one of the punishing winter storms characteristic of the region forced Smith and a contingent of men and vessels to stop at Kikotan for about a week on their way to negotiate with, and obtain corn from, Powhatan at his capital of Werowocomoco. The following passage from the Historie documents what took place:

… the extreame winde, rayne, frost and snow caused us to keepe Christmas among the Salvages, where we were never more merry, nor fed on more plentie of good Oysters, Fish, Flesh, Wild-foule, and good bread; nor never had better fires in England, then in the dry, smoaky houses of Kecoughtan

The word “merry” in the Historie is associated with leisure, money, marriage, pastime, sports, laughter, feasting, singing, and dancing—elements that were also central to Elizabethan village festive practices. François Laroque has argued that each religious celebration and season had a secular analogue; winter “revels” got an early start in November on Queen Elizabeth’s accession date, and peaked with the twelve days of Christmas, defined by its two “eves”—Christmas and New Year’s—and the Epiphany, known secularly as Twelfth Night. The fires of the Kikotan houses would have been reminiscent of solstice imagery of light amid nocturnality, and the smokiness calls to mind the centerpiece of any English Christmas celebration: the Yule log. The pagan origins of “Yule” notwithstanding, the English at Kikotan would have aware of the season’s Christian practices, including the feeding of the poor mimicked in the exchange by Mummers of song for coin and wassail, as they themselves sought succor in their time of need.

That Smith found it necessary to venture out at a time when weather and custom would have dictated otherwise showed the seriousness of their situation, and especially after having been warned by the chief of the Warraskoyack that Powhatan “hath sent for you onely to cut your throats.” But natural disasters and holidays both have a way of calling political time-outs—and, in this case, the storm and unscheduled layover could have had the effect of restoring the English to a more “holiday” attitude. A merry Christmas, as celebrated in England, would have been a time of rest, when work would have been considered a bad thing. As Laroque noted, during the Christmas season “time was not conceived as a regular continuum,” and the presence of a Lord of Misrule would have encouraged the flaunting of convention. At Kikotan, the English would have received a musical welcome as part of their hosts’ own traditions of greeting, parting, worship, mealtime, and entertainment, and on New Year’s Day—which the English spent at Kikotan—it would have been customary for presents to have been exchanged. None of this is documented in the narratives left by the participants, but an examination of contemporary English festive practices might help explain what Smith meant when he used the word “merry.”

Though various English festivals may have belonged to distinct seasons, their elements of music, dance, and themes moved fluidly across the calendar. Robin Hood may have been most closely associated with the grotesque characters of the Morris dance, and the Morris itself might have been most often associated with spring festivities, or the Mummers’ plays with Christmas or Easter, but the same instrumentation and tropes animated all—so much so that secondary commentators over the last century have struggled to explain the overlap between various forms of dance, or even the exact boundaries of dates and practices.

Laroque also identified ambiguity in “meaning and functions,” for while “the essence of these festivals lay … in the music, the dancing, the movement and colour,” they also brought “foreboding” and “boos of derision,” making festivals “essentially … two-edged affairs.” This ambiguity could have religious dimensions—”Morice dauncers” with “devellishe inventions” on St. Bartholomew’s Day “shame[d] not in ye time of divine service, to come and daunce about the Church”—but also raised the specter of violence. Laroque specifically connected “the uproar of the Morris dance” to “the description of martial music,” as in the case of a 1598 Ascension Day celebration in Oxford with “drum and shot and other weapons.” Such accounts suggest a sense that “merriment” had an inherent potential to get out of hand and become “a vehicle of discord, exclusion and chaos,” whether in the thematic oppositionality of festive symbols—snowballs at Midsummer, roses at Christmas—or the characterization of Mummers as “troupes of decked-out musicians who would suddenly invade homes,” posing as much of a threat to public order as to piety. Yet, as Christopher Marsh has pointed out, drumming that was both “festive” and “combative” could also “conceal a warning within the sounds of celebration” when deployed by town officials, who frequently hired drummers or invested in drums themselves.

How would the musicality of this merriment have translated to Christmas in the Chesapeake? Historical Anthropologist Ian Woodfield’s findings, and Hakluyt’s travel narratives specifically, suggest that many types of musical instruments could have been present at Jamestown, whether or not specific documentary evidence for their presence survives. The work of multiple disciplines has sometimes helped to bridge these evidentiary gaps, such as when archaeologists found evidence of jew’s harps at sites around Jamestown that could be connected to numerous accounts of that instrument’s use in trade with Native peoples. Absent those connections, though, there are nevertheless three types of instruments (or four, if you include the human voice and body) documented as being used by the English at this time and place: the trumpet, the drum, and the combination of tabor pipe and drum.

In the overlapping world of English festivities, no instrument was more commonly mentioned than the original one-man-band, the tabor pipe and drum. This musical contrivance allowed a single musician to play a melody on a pipe designed to be played with one hand while keeping a beat on a drum with the other. Significantly, taboring labors under the same kind of ambiguity noted for secular festival practices. Woodfield found the instrument serving the Elizabethan Navy as one of its “instruments of warlicke designes” in the “usual military band,” and at least one example of the instrument’s presence in a military setting suggests a hierarchy of use in which the lowly tabor may have been regarded as inferior. As reported in Principall Navigations, Captain Luke Ward, vice admiral to General Edward Fenton in the latter’s 1582 unsuccessful attempt to find a Northwest Passage by way of China, carried “trumpets, drum and fife, and tabor and pipe” on his “skiffe,” while his superior, “the generall in his pinnesse,” had “his musicke, & trumpets.” This musical combination serenaded the representatives of the governor of St. Vincent down the river, punctuated by an even more intimidating aural expression: a “salute” in the form of “a volley of three great pieces out of ech ship.”

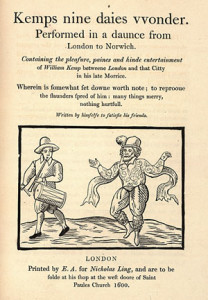

If there were such a hierarchy of instrumentation, it could have been purely functional; volume-wise, the tabor pipe would have been no match for the sonic capabilities of the trumpet noted by Barbour. The distinction could also be attributed to taboring’s humble pastoral associations. John Forrest has argued that its cousin, the Morris dance, passed only gradually from royal to rural use between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, a trajectory the tabor pipe and drum traversed, too. But by the turn of the seventeenth century, the instrument’s association with rustic entertainments was reinforced by its use by professional comic actors—the “clowns” and “fools” of the early Shakespearean stage, including some of the most famous theatre celebrities of the day. The most visible examples, Richard Tarlton and Will Kemp, both famously performed the dances most closely connected to the instrument, the jig and the Morris. As noted in Shakespearean scholarship, later “fools” weren’t quite so “foolish,” and Kemp’s celebrated buffoonery may have led to both his departure from performance and partnership at the Globe Theatre as well as his subsequent (in)famous publicity stunt, a “Morrice daunce” to Norwich in 1600.

But a lower status for taboring would also be consistent with the often terrible reputation the instrument enjoyed. “Baudie Pipers and thundering Drummers” were likely “to strike up the devils daunce withall,” and even on an ordinary “Lord’s Day,” one pious commentator complained, one could neither “read a chapter,” nor “pray, or sing a psalm, or catechise, or instruct a servant, but with the noise of the pipe and tabor.” Nor was the mischief attributed to the tabor pipe and drum purely of an irreligious nature; in a double entendre seen in other commentary on musical instruments, William Fennor wrote in 1612 of a man being cuckolded by a “knave … playing frolickly upon his Tabor.”

According to many of its critics, the remedy for the evil of taboring could be found in religion. The master in Christopher Fetherston’s 1582 dialogue against dancing cautions his student “to reioyce, not in a bawdy pype or tabor, but in the Lorde.” Yet even this prescription is ambiguous, for “Tabor” was also the name of the mountain that Christianity holds to be the site of the transfiguration of Jesus. The punning connection of the holy mount to the wicked musical instrument was not lost on the early-modern audience; Henry Greenwood, writing in 1609, may have had the linkage in mind as he condemned “unrighteous” “hypocrites” who “praise the Lord in the Tabor, but not in the dance.” The author and composer John Marbeck in 1581, too, saw good in the instrument but evil in some of its users. Acknowledging that, while “The wicked runne after the Tabor and the Flute,”

… the Flute and the Tabor and such other like things are not to be condemned, simplie of their owne nature: but onelie in respect of mens abusing of them, for most commonlie they perverte the good use of them: For certainlie, the Tabor doth not sooner sound to make men merrie, but … men are so caried awaie, as they cannot sport themselves with moderate mirth, but they fling themselves into the aire, as though they would leape out of themselves. This then … [is] a cursed mirth … that God condemned.

Marbeck encouraged restraint in such pastimes, so that God in “the ende … maie blesse our mirth.”

With respect to the winter holidays, the pipe and tabor served as well at Christmas as it did on Whitsun or May Day. The specific connection of piping to the Christmas season is made in Richard Brathwaite’s 1631 satire on pipers in Whimzies:

An ill wind … begins to blow upon Christmasseeve, and so continues very lowd and blustring all the twelve dayes … then … vanisheth to the great peace of the whole family, the thirteenth day.

Though Brathwaite’s anecdote may have had some form of bagpipe in mind—his “Inventorie” of the dead piper includes “a decayed Pipe-bagge”—Laroque argues that “pipe” in this case could have referred to either form of pipe, and certainly his evidence suggests it is the taborpipe that is associated with much of the musical mayhem of the early-modern village festival. When combined with Morris dancing, Laroque found, taboring “justly deserve(d) to be called profane, riotous and disorderly”—or, worse, in the view of Puritan critic Philip Stubbes, “a form of pagan idolatry and a homage paid to Satan.”

All of these examples suggest that the musical accompaniment the English would have been able to provide during the “merry” Christmas spent at Kikotan would almost certainly have included the taboring and dancing so completely conjoined with the English village practice. If so, this would mean the Kikotans would have had ample opportunity over this period of winter sequestration to become familiar with the instrument in its most English, most intimate, most comical, and least threatening expression, without the layers of violent or warlike ambiguity attached to the instrument at home or in battle.

In the months that followed, the “merry” moment that had welcomed 1609 faded as the parties on either side of the cultural divide grew more aware of the unsuitability of the other as potential trading partners and military allies. This difficult year of intercultural tension, drought, and privation marked Smith’s departure from the colony and ushered in both the First Anglo-Powhatan War and the “Starving Time” that nearly ended the Jamestown project—though recent scholarship suggests political reasons why Percy’s and other accounts may have exaggerated some of the more dire claims, including cannibalism. In spring 1610, a new governor, Sir Thomas Gates, finally arrived in Virginia after having been shipwrecked the previous year at Somers Island (the present-day Bermuda) in a widely publicized story that may have inspired Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Gates packed up the survivors and headed back down the James with the intention of returning to England, only to be met by reinforcements led by Thomas West, Lord De La Warr. Fresh from the brutal English campaigns in Ireland, the new commander would soon set a more aggressive tone for encounters with Powhatan peoples. This growing tension provides the context for one final musical encounter between Kikotans and English, involving a military ruse, and a taborer.

By the summer of 1610, the Kikotans and English had had ample opportunity to familiarize themselves with each other’s musical presentation styles for greeting, and for war. There was room for misinterpretation, of course; one early example recounted in the Historiefrom Sir Richard Grenville’s 1585 Roanoke expedition involved “a song we thought for welcome” but which their Native ally Manteo told them meant “they came to fight.” But many more examples from encounter literature suggest that both sides knew exactly what to expect, musically, preceding a fight. The Historie’s description of Natives’ “manner of Battell” told how warriors would “[approach] in their orders … leaping and singing after their accustomed tune, which they onely use in Warres,” and how, at “the first flight of arrowes they gave such horrible shouts and screeches, as so many infernall hell-hounds could not have made them more terrible.” Smith gave no examples of the English use of music at the onset of any attack in Virginia before 1610, but given the paucity of English musical references in the Historie, this is perhaps not surprising. But elsewhere, his descriptions of the specific role of trumpeting and drumming before and after battle agree with an account that the Historie did report took place just two years later, in 1612, during an incident on the way to Pamunkey following the kidnapping of Pocahontas. Sir Thomas Dale’s forces offered a truce, but, “if they would fight with us, they should know when we would begin by our Drums and Trumpets.” The consistent English descriptions of trumpet-and-drum salvos at the beginning of battle suggest what Natives might have expected from a hostile force. What they might not have expected … was a taborer.

The ambiguity of taboring’s martial and merry utility, and,very likely, the experience of the “merry” Christmas at Kikotan, would have combined with the familiar use of music in the greeting practices of both cultures to create, on July 9, 1610, the deceptive conditions that Percy’s account made clear were the intent:

… S[i]r Tho[mas] Gates beinge desyreous for to be Revendged upon the Indyans att Kekowhatan did goe thither by water w[i]th a certeine number of men, and amongste the reste a Taborer w[i]th him. beinge Landed he cawsed the Taborer to play and dawnse thereby to allure the Indyans to come unto him the w[hi]ch prevayled. And then espyeinge a fitteinge oportunety fell in upon them ….

The attack resulted in the slaughter of several Natives and the removal of all Kikotan inhabitants of the lower Virginia peninsula, allowing the English to seize their lands and occupy their homes just in time to harvest the corn—the same homes where, less than eighteen months earlier, during Christmastide, their fellows had been given shelter from the storm, in surroundings the English had compared favorably to their own distant homes.

In an ironic postscript, Smith used a familiar contemporary analogy to the tabor to provide, in the Historie, his “opinion” on some of the skirmishes that followed a later massacre—the well-publicized 1622 “Virginia Massacre” of English by Natives that helped fuel the colony’s transition from private to royal governance. Smith advised the use of “patience and experience” in subduing the Native population, asking, “will any goe to catch a Hare with a Taber and a Pipe?” But in the case of the 1610 Kikotan massacre—a tale that Smith surely knew—that is exactly what the English did, and successfully, through subterfuge that benefited from the musical encounters of 1607-1610.

Those encounters were all but lost after the founding of Hampton, Virginia, much like the Native people who took part in them. The Kikotans who survived would assimilate into other Powhatan groups, the “small tribal islands in a sea of non-Indians” described by anthropologist Helen Rountree. A tiny fraction of their pre-contact extent, Powhatan peoples saw their culture eroded not only by time, but likely, too, by the viciousness of later ages culminating in the “Jim Crow” era, where the myth of “separate but equal” tended to further silence old practices in the face of race-based legal strictures that accompanied the designation “colored.”

Today the name Kikotan—spelled in the English way, “Kecoughtan”—is most familiar on Virginia’s lower peninsula as the name of a high school whose sports teams bear the sobriquet “Warriors;” the school is located near the headwaters of the river renamed “Hampton,” like the town, likely for Virginia Company patron Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton. If you search for “Historic Kecoughtan” online, you find not the legacy of a Native people but a “17th Century Trading Plantation” that adopted the name of the land originally named for, and subsequently wrested from, the earlier inhabitants. The name Kecoughtan remains, too, on the easternmost section of an ancient road that today takes Route 60 from near where the Kikotan village once stood past the exclusive Wythe neighborhood toward the James River and the plantations that mark English expansion into Powhatan lands to the west and north. The site of the original village became a neglected corner of an otherwise thriving early American town, occupied by freed slaves after the Civil War before being incorporated within the grounds of Hampton University (formerly Hampton Institute), which itself was founded by another culture whose labor was appropriated—like the Kikotans’ land—to enrich the English-speaking colonial project and the nation it subsequently spawned.

The music that animated the Anglo-Kikotan moment can no longer be heard. Yet in reconstructing those first, brief musical encounters of 1607-1610 from shards of evidence mined from the documentary record, we add a dimension of aurality to our understanding of a very complex period of encounter, one founded on various hopes and misunderstandings, characterized briefly by possibly pragmatic yet undeniable generosity, and ultimately undone in violence and betrayal, where two cultures collided, musically, on the banks of the Kikotan.

Further reading

The 400th anniversary of Jamestown produced considerable scholarship; here are a few representative publications.

Primary works by John Smith, including A Generall Historie of Virginia (1624) and other texts referencing music, appear in Philip Barbour’s The Complete Works of Captain John Smith, 3 vols. (Williamsburg, Va., 1986). George Percy’s account is included in its entirety in Mark Nicholls’s article, “George Percy’s ‘Trewe Relacyon:’ A Primary Source for the Jamestown Settlement,” in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 113:3 (2005): 212-275. Larger secondary collections of primary documents of the period include James P. P. Horn’s Captain John Smith: Writings with Other Narratives of Roanoke, Jamestown, and the First English Settlement of America (New York, 2007), and Edward Wright Haile’s Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony: The First Decade, 1607-1617 (Champlain, Va., 1998, 2000).

Secondary evaluations of the period include Karen Ordahl Kupperman’s Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America (Ithaca, N.Y., 2000), which examines political stressors at the time of English arrival in the Chesapeake; her follow-up, The Jamestown Project (Cambridge, Mass., 2007), puts the story in its broader early-modern and Atlantic contexts; and a forthcoming article, “The Language of Music in Early-modern Encounters,” explores the use of music as communication by many early-modern cultures that otherwise shared no language in common. Helen C. Rountree’s Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown (Charlottesville, Va., 2006) provides a Native perspective and applies anthropological methods to early encounters in the Chesapeake region. David S. Jones’s examination of the demographic crisis in Native populations of the Western Hemisphere following the arrival of Europeans appears in “Virgin Soils Revisited,” in The William and Mary Quarterly 60:4 (October 2003). Rachel B. Herrmann’s reconsideration of the Jamestown “Starving Time” appears in “The ‘tragicall historie’: Cannibalism and Abundance in Colonial Jamestown,” in The William and Mary Quarterly 68:1 (January 2011): 47-74. An introductory ethnomusicological overview of Native musical traditions is provided in Ellen Koskoff’s Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The United States and Canada (New York, 2001).

Beyond the Chesapeake, the period of English forays into the “ocean sea” is explored in Peter C. Mancall’s Hakluyt’s Promise: an Elizabethan’s Obsession for an English America (New Haven, Conn., 2007). Great detail on the musical dimensions of the period is provided by Ian Woodfield’s English Musicians in the Age of Exploration: Sociology of Music No. 8 (New York, 1995). For musical festivities in the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods , see François Laroque’sShakespeare’s festive world: Elizabethan seasonal entertainment and the professional stage, trans. Janet Lloyd (Cambridge, 1991). Christopher Marsh explores the duality of drumming in “‘The Pride of Noise:’ Drums and their Repercussions in Early Modern England,” in Early Music 39:2 (May 2011): 203-216. John Forrest assesses taboring and much more as part of The History of Morris Dancing, 1438-1750: Studies in Early English Drama (Toronto, 1999), and Max Thomas discusses Kemp, Morris dancing, and taboring in “Kemps Nine Daies Wonder: Dancing Carnival into Market,” in PMLA 107:3 (May 1992): 511-523.

I would also encourage visiting the spaces on Virginia’s lower peninsula inhabited by Kikotans and English in the years 1607-1610, and the venues that preserve artifacts of the same. In addition to the familiar Jamestown Settlement and Historic Jamestowne at the southern terminus of Virginia’s Colonial Parkway, the Pamunkey Indian Tribe Museum, located on the Pamunkey Reservation created by treaty from ancestral lands in 1646, “teaches about the Pamunkey people and their way of life throughout history, from the ice age to the present.” The Hampton University Museum, on the grounds of Hampton University—site of the Kikotan village—maintains a permanent collection entitled, “Enduring Legacy: Native Peoples, Native Arts.” And the Hampton History Museum, located near the site of the original village, has a large collection of Kikotan and colonial English artifacts of the period.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges with deep gratitude the support of the late Dorothy Rouse-Bottom, who made possible the conference for which an earlier draft of this paper was produced, and without whose support the 400th anniversary of Hampton might have passed without a single official notice of the Kikotan massacre; also, the scholarship and inspiration of conference panel members Karen Ordahl Kupperman and Helen C. Rountree, who have offered many helpful comments to, and much encouragement during the writing of, several incarnations of this paper.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

Jeanne Eller McDougall brings a life-long love of traditional song and music to her PhD candidacy in history at the University of Southern California, and is finishing a dissertation on political song in British colonial America, 1750-1776. She was a 2011-2012 USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute Fellow, and a Michael J. Connell Foundation Fellow at the Huntington Library for 2011-2012.