Indiana’s Infidel Congressman

Locals refer to southwestern Indiana as “The Pocket,” but politicians know this region by a more ominous name: “The Bloody Eighth.” The counties that fan north and east from the confluence of the Ohio and Wabash Rivers anchor Indiana’s present-day Eighth Congressional District. In recent decades, candidates for national office in this district have waged savage partisan battles only for winners to find themselves retired in the next election by voters little enamored with incumbents. As a result, Indiana’s Eighth is a swing district in an overwhelmingly Republican state. Rough-and-tumble elections have characterized Pocket politics since the 1820s when it was then the heart of Indiana’s First Congressional District. During the 1840s, local voters alternated between Democratic and Whig Representatives in fairly rapid succession. For a time in this decade of political ferment, Democrat Robert Dale Owen represented the people of what might be called Indiana’s “Bloody First.”

Owen won election to the House in 1843 following a successful career in the Indiana General Assembly during the late 1830s. Owen’s political success in a district known for its fickle electorate indicates where he stood on the major issues that concerned the 28th and 29th Congresses. His tenure in office coincided with disputes between the United States and England over land claims in the Pacific Northwest, the annexation of Texas, debates over slavery’s westward expansion, as well as long-standing matters of internal improvements and government fiscal policy. On each of these issues, Owen voted as a fairly moderate western Democrat. When Democrat James K. Polk won the White House in 1844, Owen found himself in the mainstream of his party.

At first glance, Owen’s political career is notable primarily for his close adherence to the Democratic status quo of the day. Moreover, Owen might be considered a rather unremarkable politician in an era when more colorful personalities haunted Congress. Owen could easily disappear into the nation’s tumultuous political seas of the 1840s only remembered today, if at all, for his integral role in creating the Smithsonian Institution toward the end of his time in the House. However, Owen’s contemporaries knew more about him than simply his record of mainstream Democratic positions. Owen arguably stood out like few other Democratic politicians of his day because his life before elected office was so unlike his peers. Owen had a past, and pasts—in the 1840s just as now—could exalt or crush political fortunes.

Owen’s election to Congress attracted national attention because it occurred at a moment in American life when faith was an intensely bipartisan concern.

Clues to Owen’s past and how it shadowed his reputation appeared during his first campaign in 1836 for a seat in the Indiana General Assembly. A Whig newspaper in Massachusetts succinctly reported the results: “Robert Dale Owen, another precious Infidel, has been elected to the Legislature of Indiana, through the influence of Van Buren’s friends in that State.” Whig editors and operatives in Indiana similarly characterized Owen’s candidacy. Americans used the term “infidel” in the early nineteenth century to describe anyone who criticized, especially in public ways, widely accepted Christian beliefs along with the moral principles and social institutions deemed necessary to their survival. To contemporary observers, Owen wasn’t an ordinary infidel. Rather, many would have known him as an infidel operative at the center of an expanding network of associations and newspapers dedicated to a belief that traditional religion stood on a shaky intellectual and moral foundation that was about to crumble under the force of free inquiry. Infidel Owen’s election to state and, eventually, national offices activated long-standing anxieties that anti-Christian ideas had broad popular consent in the United States.

Owen’s election to Congress attracted national attention because it occurred at a moment in American life when faith was an intensely bipartisan concern. Nearly all political observers in the 1840s agreed that Congressman Owen held provocative religious opinions. Partisans from across the political spectrum drew lessons from Owen’s political career to guide their respective parties toward future electoral victories in a society undergoing fundamental religious and economic changes. Ultimately, Whigs and Democrats in the 1840s responded to Owen’s tenure in Washington by developing ideas of religious liberty suitable to their powerful constituencies. Although Owen eventually served only two terms in Congress, his relatively brief career raised questions about religion’s place in American political life that remain unresolved in the twenty-first century.

By the time Owen ran for state office in Indiana, he had ensured his reputation as one of the nation’s most prominent infidels. In 1825, Owen had helped his Scottish industrialist father, Robert Owen, establish a socialist utopian community in New Harmony, Indiana, bringing Robert Dale Owen to the Pocket. The New Harmony community collapsed by 1829, but before its demise Robert Dale took steps that ensured his later infamy.

Most importantly, he co-edited the New Harmony Gazette with Frances Wright, another Scottish émigré. Owen and Wright doubted many of their era’s most deeply entrenched social, political, and religious values, and their newspaper became an outlet for such views. Under Owen and Wright’s guidance, the New Harmony Gazette even outlived the community, albeit as the Free Enquirer published in New York. During the 1830s, the Free Enquirer was the most important journal in the United States devoted to undermining the power of revealed religion in American life, especially Christianity in all of its forms. Owen and Wright also publicized efforts by people in towns and cities—from the east coast to the Midwest—to form societies of “free enquirers” and “moral philanthropists.” By organizing lectures and debates critical of Christian teachings and social influences, these various associations were localized expressions of the religious opinions that Owen and Wright gave continental reach in the pages of the Free Enquirer. Indeed, under their editorship, 1,000 issues of the Free Enquirer appeared every week, and local subscription agents worked in eighteen of the republic’s twenty-four states, the Florida Territory, and the British province of Lower Canada.

Owen and Wright took other steps to advance their views on religion. They published or imported controversial books by leading anti-Christian authors of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They also established New York’s Hall of Science, a prominent venue in the city for free inquiry discussions and lectures. Finally, Owen was a supporter of the Workingman’s Movement, a birth control theorist, and a critic of existing marriage laws and customs.

Aware of his reputation, Owen devised ways to improve his electability. He presented himself as a different person upon returning to Indiana from New York in 1833. Although New Harmony was a place of failed designs for Owen’s extended family, it held promise in light of his immediate concerns. He had recently married Mary Jane Robinson, the daughter of a New York merchant. Robinson was one of the female infidels who so vexed pious commentators in the 1830s. With her father’s approval, she attended Frances Wright’s lectures and events at the Hall of Science, where she first met Owen. Back in New Harmony, the newlywed Owen devoted his attention to managing and increasing the property value of his land in town. With this ambition he championed internal improvements, an issue with strong bipartisan support in Indiana. Once Owen entered politics, voters in and around New Harmony were familiar enough with Owen to know that Whig characterizations of his past were not entirely consistent with his current political concerns in the late 1830s. Finally, toward the end of his tenure as an Indiana Assemblyman, Owen distanced himself from his earlier life in terms that anticipated his moderate stance as a Congressman. “In that fresh and sanguine season,” Owen reflected, “the warm conviction of what ought to be, often precludes the calm observation of what is.” However, with maturity, Owen confessed, “One becomes less confident in one’s own wisdom and more deferring to usage and experience.”

Although Owen expressed few fixed opinions of a radical nature during his first run for Congress, equivocation wasn’t valued in the prevailing political culture. By the late 1830s, Whig partisans had successfully portrayed themselves as the party of traditional Protestant propriety and their Democratic opponents as the party of subversive infidels. The outlines of this development are fairly well known to historians of the period. Less noted is the extent to which political observers of the day understood infidelity as more than the subject of vague political threats embodied in general references to Owen or Frances Wright. Rather, they believed that infidels were a real political force with evolving partisan aims, as evidenced in Owen’s move from infidel promoter to politician. Owen’s candidacy seemed to confirm why the prevailing partisan labels were useful. Democratic writers, especially supporters of the party’s more radical positions, celebrated Owen’s political ambition because they hoped that he would champion policies to undermine the economic and moral foundations of Whig appeal. Conservative Democrats viewed his entrance into national politics ambivalently. Of course, Whig writers challenged the outcome that radical Democrats desired. They insisted that elected office would afford Owen an opportunity to advance harmful reforms under the cover of popular sovereignty. Ultimately, partisans who responded to Owen’s pursuit of national office had every reason to prevent Owen from escaping his past, to describe him as beholden to views on religion and society set earlier in his life. As a result, Owen’s actions and writings from New Harmony’s early days and from New York defined him in public opinion for the rest of his life.

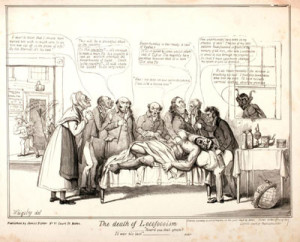

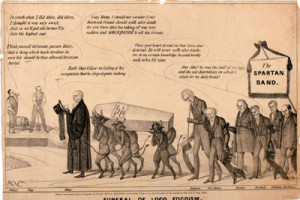

The past’s grip became instantly evident once Owen started his campaign for Congress. Critics outside of the state anointed Owen “the acknowledged leader of the Loco Foco party in Indiana” and “a declared candidate of the Loco Foco party for Congress in Indiana.” No label conjured the subversive elements within the Democratic Party more than “Loco Foco.” This name originally applied to a radical faction of New York Democrats critical of all monopolizing arrangements of state and financial power, especially banks, with strong support from the city’s working men. During a fractious meeting at Tammany Hall in 1834, the radical Democrats lit “loco foco” matches after their moderate Democratic opponents extinguished the lights in an attempt to derail their movement. By the late 1830s, Whig partisans conveniently described all Democrats as Loco Focos. Whigs enhanced their claims by identifying Owen as the party’s leader in waiting.

Owen’s brand of Loco Focoism, his critics insisted, was especially hostile to Christianity. In public addresses, Owen had denigrated “the Bible as a book of ‘marvels and mysteries,’ and ‘imaginary adventurers,’ the invention of ‘ignorant men.'” Owen’s opponents also reminded readers that he did not view Jesus as the divine son of God but as “a Democratic Reformer.” Jesus’s mere mortality was the source of his greatest influence in the world, Owen seemed to suggest, for his life provided a model for improving society, not a guide to transcendent truths. By diminishing Jesus’s true nature in order to exalt him, Owen’s ideas offered troubling “signs of the times, from which the people may take warning, before it is too late.”

Negative characterizations of Owen’s Loco Focoism were not altogether wrong. Earlier in his life, Owen had championed economic views compatible with Loco Foco positions. William Leggett, the leading Loco Foco journalist and intellectual, explained the relationship between the movement’s economic positions and religion, a connection that gave all candidates, regardless of their beliefs, an equal right to seek political office. Although Leggett did not share Owen’s religious opinions, he did argue for “perfect free trade in religion—of leaving it to manage its own concerns, in its own way, without government protection, regulation, or interference, of any kind or degree whatever.” As a result, Leggett insisted that a respected “divine” and an avowed “infidel” were equally entitled to elected positions. Although Owen would never carry the Loco Foco standard in Congress, his positions were close enough to those of leading Loco Focos that the term became a convenient badge of scorn that Whigs applied to Owen and the Democratic Party more broadly.

As the Democratic Party’s standard bearer in the late 1830s, Martin Van Buren developed an Owen problem once the Indianan’s political ambitions gained national attention. Conservative New York Democrats decried the pernicious influence of “foreign agrarians,” Owen among them, “who are now the immediate friends of Van Buren, and the recipients of his political favors.” Whig papers proclaimed that issues beyond banking and land policy connected Van Buren and Owen. According to one view, Van Buren’s positions were activated by “the leven brought to this country principally by the disaffected ‘radicals’ of Great Britain, and first infused into this community through the ‘Hall of Science’ and next through Tammany Hall, and now boldly partaken of by the chief Magistrate of the Union.” Another Whig editor asked rhetorically, “how many open and avowed infidels are there, who in other portions of the country are leaders and head-men in the ranks of the party.” Owen stood first among the Democratic leaders, but Abner Kneeland and George Chapman joined him. Kneeland was a candidate in Iowa territorial politics who had emigrated from Massachusetts after serving jail time for a blasphemy conviction. Chapman was a Democratic newspaper editor in Indiana and the former editor of the infidel Boston Investigator who supposedly toasted, “Christianity and the Banks—both on their last legs” during a Thomas Paine birthday celebration in Boston. “Verily is not a party, as well as an individual, known by the company it keeps,” concluded Whig opinion.

Owen’s record in state politics also gave Whigs fodder for attacking him and his party. In 1838 the General Assembly revised and expanded Indiana’s already liberal divorce statute. Under the law, either partner could seek divorce for specified causes including adultery, “matrimonial incapacity,” a husband’s habitual drunkenness or “barbarity,” and also the broadly worded phrase “any other cause or causes.” Indiana thus became firmly ensconced in the national imagination as the state where marriages ended quickly and easily. Owen participated in the revision of Indiana’s statute, which reflected opinions he expressed during his New York days in support of women’s property rights and against overly strict divorce laws.

Critics looked to Owen’s writings in New York and his support for Indiana’s divorce laws as proof that he endorsed a view of marriage with dangerous consequences. One especially polemic writer argued that Owen’s concept of marriage amounted to “legalized prostitution.” Once couples could end their marriage for reasons of “impatience, caprice or disgust,” it seemed certain that many would so proceed merely a month or a day after their weddings. Marriage would no longer serve as a God-ordained covenant but rather a cover for licentious behavior, the critic warned. If Owen’s view of marriage had social consequences, then, other opponents argued, Owen was morally unfit for public office. Owen’s “irreligious notions,” his view of marriage chief among them, were essential to his “democratic creed.” Whigs warned that many voters might actually elect Owen and others of his ilk, but such a person could not effectively steward the nation’s interests. After all, “What regard can he be expected to pay to moral obligations, who believes himself bound only by convenience in the most important of all human relations?”

Whig portrayals of Owen as a leading voice for efforts to widen access to divorce conveniently overlapped with Whig opposition to Democratic banking policies. Drawing ideas from hard-money theorists in the early 1830s, President Van Buren proposed the creation of an independent treasury or “subtreasury” following the Panic of 1837. This plan called for the complete disentanglement of the federal government and private banks, what supporters called the “separation of bank and state.” Whigs and conservative democrats strongly opposed this plan, with some turning this proposed “divorce” in government fiscal policy to powerful rhetorical ends. It was no coincidence, according to this view, that a president controlled by Owen and his supporters would accept a policy that would unleash chaos in the nation’s economy just as sweeping rights to personal divorce would undermine the culture at large. Van Buren’s Sub-Treasury plan threatened to destroy business by discouraging personal industry. Yet the long-term consequences were even greater. Whigs asserted that Van Buren’s Sub-Treasury plan was apiece with his larger goal of consolidating all power in his hands. “Thus ‘a divorce’ of the Government from the people is sought that there may be a union of the purse and sword.” There was a direct line, so Whigs argued, connecting Owen’s idea of divorce to the destabilization of the nation’s “Republican Institutions.”

Once the votes were tallied in 1839, it became clear that Owen’s past undid his first run for Congress. George H. Proffit, a formidable Whig candidate, handily defeated Owen in the wake of an organized campaign by Proffit’s supporters to remind local voters that the Democrat had once been New York’s leading infidel. Whigs outside of Indiana also recognized the larger significance of Owen’s loss. A New Hampshire editor celebrated the “noble triumph of principle” over a “political party, which had supported for Congress a man who has delivered Sunday evening lectures on the ‘Non-existence of the Soul’—at six pence a head.” For other Whig editors, Owen’s loss taught clear political lessons about congressional elections more generally. A New York Whig newspaper recounted Owen’s ties to the city’s anti-Christian and labor activists; thus the defeat of “Owen, of Fanny Wright and Eli Moore odor” provided consolation for a larger number of Whig setbacks in the West.

Owen’s defeat also suggested how Whigs might reverse their losses in future elections. One Whig editor found it remarkable that “Fanny-Wright men” who “would vote for [Owen] on account of his well known infidel principles” never combined with “the whole ‘democratic’ strength” to bring Owen victory. This editor credited sensible Democratic voters and “the virtuous and intelligent women” of Owen’s district who “used their influence with their husbands, brothers, and sons” for preventing such an alliance. Whig observers concerned with Owen’s political ambitions thus took his loss in 1839 as an opportunity to assess their party’s future prospects.

Looking ahead, Whigs had good reason for optimism in 1839. Democrats faced external opponents and internecine clashes. President Van Buren could not escape blame for the economy’s failure to fully recover from losses caused by the Panic of 1837. Discontent with Van Buren redounded to the Whigs. Continued economic troubles intensified factionalism within the Democratic Party on issues such as slavery and banking. And as at least one Whig editor believed, Owen’s defeat suggested that religious issues could divide Democratic votes. Whig observers believed they could exploit Democratic weaknesses in order to win control of Congress and the presidency in 1840. Owen’s initial run for the House thus proved useful to a Whig opposition strategy focused on depicting Democrats as the party of dangerous ideas about markets and morality.

By concentrating their attention on Owen as the embodiment of Democratic infidelity, Whigs borrowed an opposition tactic from an earlier period of partisan conflict. Federalists in the early 1800s attacked Republican officeholders, especially President Jefferson and members of his Cabinet, by tying them to a cast of familiar deist editors and organizers, people such as the Irish émigré Denis Driscol and Elihu Palmer, an erstwhile Presbyterian minister. Similar to earlier Federalist aims, Whigs highlighted Owen’s political ambitions in order to ground their rhetoric. Rather than proffering only unsubstantiated charges of Democratic infidelity, savvy Whig partisans by 1840 provided a genealogy for the Democratic Party of their day with an important line started by Owen and the infidel community he helped build over a decade earlier.

From a Whig perspective, the fickle voters of Indiana’s First had miraculously contained Democracy’s moral threat to the republic, but the nation still needed a stronger bulwark. Whigs included Owen’s candidacy as one among many reasons why the people should give them control of Congress and the presidency. Whig responses to Owen’s failed bid for Congress in 1839 thus prefigured their larger religious campaign in the elections of 1840. In the presidential election that fall, Whigs cloaked their candidate, William Henry Harrison, and their party in the garb of Protestant moral propriety against their infidel Democratic opponents. Whigs won their first congressional majority and the White House in that election.

Owen’s fortunes improved along with those of the Democratic Party. He entered Congress in 1843 as part of a larger wave that returned Democrats to national power, gaining them a House majority in the 1842 elections followed by a congressional majority and the presidency in 1844. Since his time in Washington marked a retreat from his radical past, he adopted positions that alienated former allies but, presumably, improved his electability. For instance, in 1845 Owen supported allocating federal lands in Indiana for canal construction. According to the Working Man’s Advocate, Owen’s vote contradicted his earlier support for protection of free public lands to assist the property-less. “Mr. Owen must now be classed among the enemies of the Equal Rights of Man,” charged editor George Henry Evans. “I can only look upon Mr. Owen’s vote in favor of Land-Selling,” Evans concluded, “as I would upon a direct vote in favor of Serfdom or any other form of Slavery.” To critics such as Evans, Congressman Owen had betrayed his reform principles. Anyone with market interests in Owen’s district viewed him differently. By funneling government largesse into southwest Indiana, Owen expected climbing support when he sought re-election in 1847.

On the contrary, Owen lost reelection to a third term in Congress. This outcome surprised political observers across the nation. It caused a “Dewey defeats Truman” blunder for many papers that misreported an Owen victory. Whig Elisha Embree won the election, in part, by resurrecting Owen’s infidel past. According to one account, Embree “took the stump and read to the people from his newspapers and pamphlets, the religious views of Mr. Owen, as formerly communicated by him.” George D. Prentice, editor of the prominent Whig newspaper the Louisville Journal, praised Embree for achieving “a moral as well as a political triumph.”

Partisans farther afield explained Owen’s defeat with an eye on larger developments taking place in American life. Beginning in the early 1840s, immigration to the United States increased spectacularly; within a few years, several hundred thousand immigrants arrived annually. Between 1845 and 1854, the United States’ immigrant population grew by almost 3 million. Migrants were principally Irish and German, and increasingly Catholic and impoverished. For political commentators—Whig and Democrat like—willing to take an expansive view, the rise and fall of Owen’s political fortunes offered lessons for addressing the republic’s changing religious demographics.

Increasingly during the 1840s, nativism colored Whig impressions of American politics. They traced their nativist views to recent books such as Lyman Beecher’s A Plea for the West, published in 1835. Although principally an anti-Catholic work, Beecher was fundamentally concerned with the problem of consent, in particular the conditions that imposed necessary restraints on choice. These restraints operated tacitly on individuals based on their upbringing and cultural inheritance. Beecher, then in Ohio, compared his new home in the West to his native New England. Early New Englanders “were few in number, compact in territory, homogenous in origin, language, manners, and doctrines; and were coerced to unity by common perils and necessities.” Shared experiences—strengthened by the powerful tethers of faith, family relations, and culture—allowed individuals, so Beecher believed, to make choices toward a common good. To the contrary, westerners, Beecher argued, were a “population … assembled from all the states of the Union, and from all the nations of Europe, and is rushing in like the waters of the flood, demanding for its moral preservation the immediate and universal action of those institutions which discipline the mind, and arm the conscience and the heart.”

Beecher’s contemporaries described the consequences of religious infidelity in similar terms yet with greater urgency. Infidelity was a foreign threat that had already planted roots in American soil much to the detriment of the nation’s republican institutions. Since Owen embodied the infidel threat, his defeat in 1847 was a nativist victory worth noting.

According to a Connecticut Whig paper, the Embree-Owen contest of 1847 would have inspired little interest had it merely concerned “two Native American republicans, the one calling himself a whig and the other a democrat.” However, the election was nothing of the sort. Owen was the most recent agent in a long line of British-born radicals, beginning with Thomas Paine, whose “imported patriotism” actually produced “discontent, disorder and disregard for good government” while unsettling the established “habits of our people.” Despite the harm posed by Owen and other infidels, Americans had no choice but to accept them, their ideas, and their political ambitions. “It is quite bad enough to have these pestilent intermeddlers in our midst, and to be obliged to tolerate their impudence as private and unofficial brawlers,” the editor lamented, “but to make legislators and rulers out of such material” degraded “national character.” Votes cast by an electorate of sound morals and faith were the only hope. Whigs, and respectable Americans regardless of party, were “greatly gratified in seeing an English radical of the infidel and Fanny Wright school fail to find American Jacobins enough to elect him to the national legislature, over a citizen of the soil, a christian and a man of character.”

Owen’s defeat thus suggested how Whigs might translate nativist anxiety into electoral success. Along the way, they could limit Catholic political power while still upholding principles of religious liberty. After all, foreign-born infidels were free to believe as they pleased but voters were equally entitled to deny them political power. The same could be argued for foreign-born Catholics. By challenging Owen as a partisan infidel, his opponents contributed ideas and methods that helped transform nativism into an organized political movement determined to curtail voting privileges for even naturalized immigrants, culminating in the advent of the Know-Nothing Party in the 1850s.

Democrats situated Owen’s defeat in the same political landscape as their Whig opponents. In fact, Democrats had good reason to claim Owen as their own once he left Congress. By the 1840s, Democrats identified themselves as the party of a certain idea of religious liberty, one in which faith was incompatible with reform institutions and instances of government preference for one religious opinion over another were suspect. As a result, the Democratic Party proved popular with Protestant groups skeptical of evangelical calls for improvement, as well as communities such as Catholics and Jews who stood to gain little from the Protestant cultural order of the day. In light of the Democrats’ religious constituencies, defending Owen against Whig attacks helped them further their image as defenders of basic religious liberties and freedom of conscience. As one Democratic partisan declared, Owen’s earlier religious positions were ultimately irrelevant, as “Freedom of religious opinion must be tolerated.” By attacking Owen, Whigs betrayed their “undying attachment to Church and State.”

Following Owen’s defeat, Democratic editors defended his political record and, with even greater zeal, his character. Although Owen denied such fundamental Christian beliefs as the Trinity, his religious opinions did not detract from his ability to govern. Democratic supporters emphasized Owen’s conduct over his beliefs. “He regards a just life and pure motives, with honest conduct at all times, as of more value than empty ‘professions.'” Whigs may have achieved short-term political gain by making Owen’s religious opinions a political issue, but this strategy was ultimately unsustainable, for it was “antagonistic to the spirit of freedom” that animated the Republic.

Once the Democratic Party accommodated an infidel in its ranks, the door was open to attract other religious outsiders and immigrants. Assuming that future Archbishop of New York John Hughes expressed the general opinion of Catholic immigrants in the United States, it becomes clear why his fellow believers found a home in the Democratic Party. In a debate defending his faith and foreign birth against doubts about his allegiance to the United States, Hughes declared, “I am an American citizen—not by chance,—but by choice.” Choosing one’s allegiance, in this calculation, ensured civic virtue. The ultimate expression of this view from the Democratic perspective, one that elevates this position to one of nearly religious import, appears in Secretary of State Lewis Cass’s opinion from the late 1850s that naturalized and native-born United States citizens were fundamentally equal. According to Cass, “The moment a foreigner becomes naturalized, his allegiance to his native country is severed forever. He experiences a new political birth.” For Cass, immigrants expressed their political free will by becoming citizens.

In the end, Owen’s congressional career helped Democratic partisans articulate a political philosophy designed to win votes in an era of rising Catholic immigration. For Owen’s supporters, the “spirit of freedom” entailed a notion of choice exalted in Democratic thought, but one at odds with nativist assumptions about consent. Democratic writers were less inclined than their Whig counterparts to believe that a free person’s ability to express informed consent, and thereby participate in self-government, was determined by a specific faith, ancestry, culture, or tradition. Of course in the public realm, this concept of choice was fundamentally the privilege of free white men. However, it was also essential to broader Democratic positions on freedom of conscience, immigration, and citizenship. From this perspective, not only was Robert Dale Owen qualified for political life despite his foreign birth and anti-Christian opinions, any free white man, regardless of religious opinions, qualified for the same.

Public interest in Owen’s religious opinions revived with his return to national political life in the 1850s. Between 1853 and 1858, Owen was United States Minister to Naples, an appointment he received from President Franklin Pierce. During his time abroad, rumors spread in the American press that Owen was a Catholic convert. Owen denied these rumors after returning to the United States while affirming his respect for all religions when sincerely held. Regarding his personal beliefs, Owen tantalized the curious by announcing his forthcoming book about his religious opinions. Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World appeared in 1859.

In the company of Brazil’s Minister to Naples and members of the Neapolitan royal family, Owen witnessed “certain physical movements without material agency.” So began Footfalls, Owen’s investigation into spiritualism, or what he described as the “great question whether agencies from another phase of existence ever intervene here, and operate, for good or evil, on mankind.” For Owen, contemporary spiritualists attempted to conjure phenomena that were better explained by turning to psychological, natural, and, most importantly, historical inquiry. Owen devoted Footfalls to compiling and analyzing past accounts and explanations of spiritual interaction with the natural world. He considered a dizzying variety of evidence that past observers mistook for instances of hallucination, dreams, poltergeists, haunting, and demonic possession to authenticate spiritualist claims. Owen concluded Footfalls certain that spiritualist claims withstood tests of reason and historical investigation.

Owen’s defense of spiritualism bemused American writers. It seemed like a shocking transformation within the mind of one of the nation’s leading infidels. A reviewer of Footfalls in the Saturday Evening Post mockingly wondered what had happened to Owen’s view that “the world was completely disenchanted,” that “all the fairy wells fitted with patent pumps,” and “all the apparitions referred to indigestion.” On the contrary, by joining “the Spiritualistic ranks” Owen sparked “a decided ‘bull’ movement in the Spiritualistic market.” At least in this instance, Owen’s life exhibited the wide latitude available for personal religious choices at mid-century, preferences met without cautious toleration or unalloyed praise. Rather, such latitude was a routine feature of life in a religiously diverse society best confronted with humor, not fear.

Congressional candidates inspired by the spirit of Robert Dale Owen in the twenty-first century would likely face considerable challenges, whether running in Indiana’s Eighth or virtually any other district. The 113th United States Congress elected in 2012 was remarkable for its religious diversity, with members from some religious communities represented for the first time. Hawaiian voters were largely responsible for this development. They elected the first Hindu to Congress, who filled a House seat vacated by Mazzie K. Hirono to become the Senate’s first Buddhist. Outside the Hawaii delegation, two other Buddhists won re-election to the House in 2012 as did two Muslims, joining a body in which Jews are also fairly well-represented. Nevertheless, Congress remained majority Christian, with Catholics the largest single denomination. All of this according to “Faith on the Hill: The Religious Composition of the 113th Congress,” a recent report by the Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project.

Of the many fascinating details in the Pew report, one stands out in particular. The center classifies only two percent of Congress as “nones.” The beliefs of these members are difficult to pin down. Some refuse to specify, one claims humanism, and Congresswoman Tammy Duckworth of Illinois is listed as a deist in some sources, a label she hasn’t actively denied. “Nones,” as defined in another Pew study, include atheists and agnostics but also adults who understand themselves as spiritual but not interested in joining a specific religious community. What nones share in common is a sense that organized religion has no special claim to morality while, at the same time, it has become too intertwined with money and politics in pursuit of power. As the Pew report notes, nones are likely the most underrepresented group in Congress. Nones, according to recent surveys, comprise twenty percent of the adult population in the United States. Their numbers are also growing quickly, especially for people under the age of thirty. Other indications suggest that their opinions on religion are relatively fixed, which means they are more likely to remain nones throughout their lives.

Although not a perfect fit, a comparison of today’s nones to the early republic’s infidels illuminates larger themes about the relationship between American religion and politics, past, present, and future. Throughout American history, religious positions viewed as overly critical of traditional faith claims or institutions consistently cross a threshold of acceptable opinion in terms of electability. Exploring moments when this threshold is breached, as with Owen’s election, or broadened reveals much about historical changes in the relationship between religious belief and public life. The political successes of Catholics and, to a lesser extent, Mormons—groups despised as strongly as infidels in the nineteenth century and even later—emphasize this point. However, if the nones continue their “rise,” as the Pew Research Center puts it, the United States could be on the verge of more polarizing battles over a range of religious and moral issues, especially since nones are most passionate about issues that indicate organized religion’s influence on society, and they currently identify overwhelmingly with one political party, the Democrats. Perhaps the spirits of late religious controversies are determined to rap in the Capitol for years to come.

Further Reading:

Richard William Leopold, Robert Dale Owen: A Biography (Cambridge, Mass., 1940) remains the most thorough biography of Robert Dale Owen, especially concerning his political career. For excellent overviews of the relationship between partisan politics and religion in the antebellum United States, see Daniel Walker Howe, “The Evangelical Movement and Political Culture in the North During the Second Party System,” Journal of American History 77 (1991): 1216-1239, and Richard J. Carwardine, Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (Knoxville, Tenn., 1997). For readers interested in exploring the Pew Research Center data about contemporary religion and politics, see “Faith on the Hill: The Religious Composition of the 113th Congress.”

Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s(New York, 1992).

Val Nolan Jr., “Indiana: Birthplace of Migratory Divorce,” Indiana Law Journal 26 (1951): 515-527.

Eric R. Schlereth, An Age of Infidels: The Politics of Religious Controversy in the Early United States (Philadelphia, 2013).

Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York, 2005).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3 (Spring, 2015).

Eric R. Schlereth is associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Dallas and the author of An Age of Infidels: The Politics of Religious Controversy in the Early United States (2013).