“Derry Down” and the XYZ Affair

Listen to this:

Example 1: “Derry Down.” All audio examples and transcriptions created by the author.

This is “Derry Down,” an English ballad that was popular in the United States in the late eighteenth century. With its regular phrases and lilting melody, it is easy to hear why this song was well liked, but who could have predicted this unassuming tune could become a musical touchstone for political debates? Yet it did.

A history of the early republic could be told through song, for virtually every event in domestic and foreign politics was reflected in popular music. As partisan wrangling dominated early national politics, popular songs were regularly deployed by writers, editors, publishers, and compilers eager to traffic in those most addictive goods: political news and opinion. Hastily penned lyrics appeared on single sheet broadsides and in songsters (pocket-sized bound volumes), in plays and pedagogic books, and on the pages of newspapers and periodicals. Because sheet music was a specialized subset of the print trade, most of these songs appeared with lyrics only, the tune listed by name directly under the song title. British tunes such as “God Save the King,” “The Vicar of Bray,” and “Yankee Doodle” were among the most frequently featured songs because they were familiar and convenient. Despite the seeming dissonance between the songs’ origins and their use in post-Revolutionary America, Federalists writers at one end of the political spectrum and Republicans on the other end shared this pool of tunes when fighting their proxy political battles in music.

“Derry Down” was frequently recruited as a weapon in those battles, one of many songs co-opted by partisan lyricists in the ever-escalating competition to shape the nation’s political beliefs in the 1790s. Songs set to “Derry Down” began appearing in the American colonies in the 1770s, when both loyalist and patriot writers adopted the tune to propagandize during the Revolutionary War. In England “Derry Down” was typically used to present humorous stories and political topics, often tinged with wicked sarcasm and biting satire, and these songs were republished frequently in America in the 1780s and 1790s. More than two dozen discrete versions appeared by 1800, always without music. (The tune’s distinctive refrain, “Derry down, down, down, derry down,” which was retained with each new set of words, made it highly recognizable for singers, listeners, and readers.)

When the international diplomatic debacle known as the XYZ Affair erupted in April 1798, “Derry Down” was ubiquitous in the musical responses that popped up in the print sphere. This scandal, named for the code names of the offending French officials (“X,” “Y,” and “Z”) who had insulted and attempted to extort bribes from American envoys in Paris, sent jarring political and musical shockwaves across the Atlantic Ocean. Incensed Americans jettisoned once-popular French songs like “Ça Ira” and the “Marseillaise,” which were replaced by gleefully patriotic ditties such as “Hail Columbia” and “Adams and Liberty.” Savvy Federalist scribblers, seeing an opportunity to score political points against French-sympathizing Republicans, generated aggressively partisan songs that expressed their self-righteous indignation. Featuring bellicose verses directed against the French, these songs obliquely chastened Republicans for their foreign friends’ treachery. For example, the hyper-Federalist collection of songs, The Echo, or Federal Songster (published in Brookfield, Mass., in 1798) included a version of “Yankee Doodle” featuring the lines, “If Frenchmen come with naked bum, / We’ll spank ’em hard and handy.” The emphasis on “spank” is in the original.

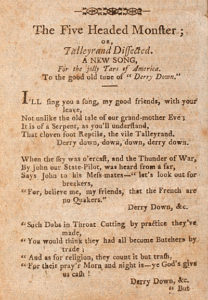

Particularly popular was a version of “Derry Down” titled “The Five Headed Monster; or, Talleyrand Dissected. A new song for the jolly Tars of America,” which appeared in New York’s Commercial Advertiser on August 4, 1798. “The Five Headed Monster” was repeatedly republished in the final years of the eighteenth century, appearing in six newspapers in New York and New England in August and September 1798 alone, and in James Springer’s Federalist Songster, published in New London, Conn., in 1800. (This was not the only use of “Derry Down” in answer to the uproar; another version appeared the following year in New Jersey’s The Centinel of Freedom on September 10, 1799.) “The Five Headed Monster” recounts the diplomatic misadventures suffered by the U.S. envoys. Although the scandal was based on insults and extortion, an escalating maritime drama underlay French-U.S. tension, and this theme was picked up in the song. French ships had been attacking U.S. and British vessels since the outbreak of French-English aggression in 1793. Following the U.S.-Britain Jay Treaty of 1795, which French and American Republicans alike viewed as dangerously conciliatory to Britain, French attacks on American ships increased. With the election of Federalist John Adams as president in 1797, French treatment of the United States grew still more hostile. Particularly outrageous to Americans was France’s stated plan for American sailors: when the French seized British vessels, any American sailors who had been forced to work on those ships would be treated as pirates.

This naval preoccupation is evident in “The Five Headed Monster.” Highlighting the duplicity of the French government (the so-called “Five Headed Monster”) and sympathizing with the plight of American sailors (called “tars”), it adopted the colloquial style of a sailor song to capitalize on Federalists’ newfound popularity. President Adams is depicted as the “State-Pilot” who addressed his “mess-mates” in the second stanza:

When the sky was o’ercast, and the Thunder of War,

By John our State-Pilot, was heard from a far,

Says John to his Mess-mates—”let’s look out for breakers,

“For, believe me, my friends, that the French are no Quakers.”

The envoys, too, are presented as lusty tars, crying out “Avast!” when confronted with French foreign minister Talleyrand. The minister and his aides are cast in the roles of piratical villains, deemed thus in the lyrics: “You’re a plundering blood thirsty, vapouring crew.” Audiences in 1798 would have understood that the faux-sailor song was meant as a reminder of the many reasons for Francophobic ire, by extension promoting the Federalist Party’s saber-rattling response.

A song like “The Five Headed Monster” wears its political heart on its sleeve. But while the lyrics conveyed forceful messages to the eighteenth-century public, the music also spoke to listeners. Perhaps it didn’t communicate in terms as literal as the words, but “Derry Down” carried cultural and political connotations, and listeners could decode these musical signals. Moreover, the style of the melody itself set the tone by which the words were interpreted. Thus, uncovering the meaning of the music can help reveal the significance of such popular political songs.

Historians typically shy away from discussions of music’s musicality, but by doing so they unintentionally neglect the important emotional and connotative dimensions that make music meaningful. Music can track historical events, commenting on and illuminating facets of the past. But it does more than that: it can also expose underlying cultural trends, and often taps into historical characters’ personal experiences. What follows, then, is an exercise in using methods of the scholarly study of music to uncover the unspoken meaning of the song “Derry Down.” Much like art historians, musicologists study musical works as aesthetic objects and contextualize music in history. We examine music making as a process of social and cultural expression, and analyze the intersection of music and philosophy, psychology, and related fields. As a discipline with nineteenth-century German origins, musicology has traditionally taken Western classical music as its object of study, but today musicologists are an omnivorous sort, eager to pursue an ever-growing variety of music and increasingly taking cues from ethnomusicology’s openness to music from a range of times, places, and peoples. Play us some music, and we want to listen carefully through our musicological headphones and peer closely through our musicological spectacles.

Popular music in early America poses certain challenges to the musicologist. Songs are like little knots with several strands that need to be unraveled. As I already noted, most often the sources do not contain any actual music, only lyrics, so the first task is to identify the tune and find out what it sounded like. In the cases where the intended tune is not indicated, when telltale textual signs (like an unusual poetic meter) are lacking, and there is no recognizable refrain, this can be next to impossible, stopping a musicologist in her tracks. But when the tune is identified in the source, as in the case of “The Five Headed Monster,” this first task is easily accomplished thanks to collections of English ballads and popular songs that provide commonly received versions of the melody. Once we know what the tune sounds like, we can evaluate the relative merits of different settings and speculate about the evolution of musical taste in America.

We could stop there, contented with our detective work and critical assessments, but there is a second, trickier task that beckons: to understand what connotations this music carried in late eighteenth-century America. This is an elusive but more rewarding goal, and two musicological paths lead to it for “The Five Headed Monster.” One path follows the tune back in time, uncovering the melody’s history and showing how that background influenced Americans’ taste for the tune in the late eighteenth century. The second path focuses on the late 1790s, considering how “The Five Headed Monster” was consumed—if it was performed, how it circulated, and thus what the social and political reverberations of the song could have been. As we shall see, both these lines of questioning force us to grapple with the fact that the tune was not a fixed artifact but a dynamic entity. The tune itself changed over time, and its meaning also changed as each new set of lyrics left a residue on the melody.

The immediate pay-off of this musicological investigation is twofold. The evidence is scanty and difficult to parse, but by working with it we come to a fuller understanding of the responsive quality of early American musical life, which was characterized by audiences’ tastes for simple but catchy melodies, music from abroad, and densely referential and clever treatment of cultural and political texts. At a deeper level, these materials probe the connection between music and politics and the relationship between music and identity—complex topics of ongoing interest in musicology that also resonate with many other disciplines.

Tunes can tell many stories, and “Derry Down” is no exception. In the century that preceded the XYZ Affair, “Derry Down” played myriad roles: it represented a folkloric take on English hierarchy in the late seventeenth century; it tracked the rise of commercialized popular music, metaphorically moving from the country to the city in the first half of the eighteenth century; and it participated in the large-scale transfer of cultural artifacts and practices from Britain to the American colonies that accelerated rather than slowed as the eighteenth century drew to a close. During the eighteenth century, as the accidents of transmission beset the melody’s contours and rhythms, it gradually changed. The tune’s connotations also changed, as the melody evolved and as new layers of meaning accumulated with each additional set of lyrics. By 1798, the many versions of “Derry Down” jangled against one another, and we can listen to the clanging of the rich cultural heritage that accompanied the musical responses to the XYZ Affair.

There are two kinds of questions we can ask about a tune’s background, and both pertain to change. First, we ask about the structural elements of the music—did the music itself change over time? Second, we ask about the cultural significance of the music—what meanings did people invest in the song, and how did those meanings change over time? We are hunting down clues about how the music sounded, and how that music made people feel. Understanding how music changed without knowing why is dissatisfying. Understanding how individuals felt about music without knowing what the music was yields an incomplete view of the past. That is why these two lines of questions work best together. As with a surprising new pitch in baseball, we want to understand what is different and how it works, why the change was made, and how players reacted to it.

Within the larger frameworks, which we might call “the music itself” and “music’s meaning,” are nested many other possible questions, most notably questions about musical taste and music’s social role. What about this tune made it desirable for frequent recycling? How did the song’s genre (a ballad) bear upon its appeal? What variants of the tune developed when it was transmitted orally, and what do those changes tell us about how the song was being used? In a larger study, we might ask what such modifications to the melody reveal about the geographic displacement of performers, and how such ruptures led to innovations in oral and written sources. At a theoretical level, we could ask about the abstract ideas tied to the melody. These would be ideas with which the lyrics interacted obliquely or challenged head-on, and we could analyze how those ideas morphed over time.

Orienting ourselves toward communities (the typical domain of ethnomusicologists), we might ask questions about the groups of people the tune excluded or included, or what it meant when competing groups each claimed the tune as their own. Such questions lead to far-reaching reconsiderations of how we organize and study music, especially songs like “Derry Down,” whose versions seeped across national boundaries and appeared on several musical platforms—lowly broadside ballads and middle-brow comical ballad operas, for example. With these questions, tunes like “Derry Down” become kaleidoscopes. Angled to catch the light, they reflect different facets of history through their prisms.

The process by which new versions of “Derry Down” came about in the first place has a long history. Fitting a preexisting melody with new words is called contrafacting, and the resulting new song is a contrafactum (pl. contrafacta). For example, “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” is a contrafactum of “God Save the Queen.” In Europe, sacred and secular contrafacta date from the medieval period, although the practice is much older—Middle Eastern sources show contrafacta from the fourth century. Contrafacting a melody wholesale was convenient for purveyors of song in the eighteenth century because using a familiar melody meant no music had to be printed, and consumers could immediately sing the new song. In some cases, the contrafactum separated entirely from the cultural milieu of previous versions. For instance, a bawdy secular song could be sacralized, adopted into the liturgy and divested of its profane associations. In other cases, a tune carried its connotations with it from version to version, inking every set of new lyrics with an unwritten secondary message. Such messages served as powerful reminders of tradition and heritage, even when the lyrics themselves represented a complete break with the past. Like many popular melodies in late eighteenth-century America, new versions of “Derry Down” referenced the song’s past simply by labeling the tune with one of its traditional English titles. With these constant reminders, audiences were attuned to the underlying connotations the tune carried from previous contrafacta.

The earliest version of the “Derry Down” ballad dates from late seventeenth-century England. Ballads, a genre of strophic narrative songs that emerged in the late-Medieval period, offered an entertaining way to tell a story, encouraging communal singing on the refrain. A vogue of satirical, critical, and even rebellious ballads developed in the British Isles in the seventeenth century, and “Derry Down” seems to have grown out of that trend. The ballad genre flourished in the eighteenth century, fueled by antiquarians’ fascination with the past and aided by the print trade’s growing capacity for disseminating music. Broadside ballads abounded, and the ballad opera helped divert the traditional story-telling function of the genre down a still more commercially viable avenue. More than a hundred versions of “Derry Down” appeared in the eighteenth century, making it one of the most popular tunes of the era. The song was associated with rather sharp-tongued comedy from the beginning, and by the end of the century it was firmly tied to social and political satire and farce.

The first printed version of “Derry Down” was a broadside ballad titled “A New Ballad of King John and the Abbot of Canterbury,” which was printed for P. Brooksby in London sometime between 1670 and 1696. Identifying the tune as “The King and the Lord Abbot,” the Brooksby print of “Derry Down” contained no music, but does have the characteristic refrain, “Derry down, down…,” which implies a tune. The first printed music appeared in 1700, in Wit and Mirth; or, Pills to Purge Melancholy (fig. 1 shows the 1719 edition), a collection of songs by the successful playwright and song composer Thomas d’Urfey (1653-1723).

There are three points to note about this earliest printed source for “Derry Down.” First, the melody has five phrases, of which the first two are the same (we’d say AABCD).

Example 2: Transcription of “The Ballad of King John and the Abbot of Canterbury,” mm. 1-4.

Second, the rhythms are almost entirely straight, mostly notes of the same length, with no syncopation and nearly no dotted figures. Third, in the penultimate phrase, the melody drifts gradually down the scale from D to F#, doing so through small turning figurations.

Example 3: Transcription of “The Ballad of King John and the Abbot of Canterbury,” mm. 7-9.

As we shall see, these three elements will change over time. Also noteworthy are the presence of two elements that stay the same: the descending line in the first phrase, and the two distinctive leaps in the melody—one of an octave in the third phrase, and another of a fifth in the final phrase, shown here:

Between 1700 and 1740, “Derry Down” transformed in both small and substantial ways. In the late 1720s and 1730s, the tune was used in twenty-six British ballad operas, including the hugely successful and entertaining The Beggar’s Opera of John Gay (London, 1728). Numerous other versions lampooned authority figures, recounting social embarrassments and criticizing political misfires. One version ridiculed a gentleman for sitting on a priceless Italian violin from one of the famous workshops of Cremona. Several versions criticized Britain’s taxation policies. And a version that was particularly popular in America in the late eighteenth century recounted the foibles of a hapless and lovelorn cobbler. (This was the traditional version best known in America—most of the “Derry Down” contrafacta in U.S. sources were labeled “to the tune of The Cobbler.”)

As “Derry Down” circulated in increasing numbers of contrafacta, the style in which it was sung evolved. Printed versions show an increased use of playful rhythms and ornamental figurations. Most noticeably, the form changed from AABCD to ABCDE, with no repeating first phrase (the final three phrases remained the same). A setting of the tune for two voices and accompaniment in Henry Carey’s Musical Century (1740) shows these changes (fig. 2).

This tune is fundamentally the same as the “Derry Down” version printed in 1700, but certain superficial elements are quite different. First, we can see the same descending first phrase that appeared in the earliest printed version, but instead of repeating in the second phrase the melody hovers around G. Compare this to example 2, and the difference in form is clear.

Example 4: Transcription of “The Melody stolen … Death and the Cobler,” mm. 5-9.

Another change: the melody line (uppermost in the score) is full of dotted rhythms that give the tune a merry air. The treatment of leaps and runs is more dramatic, too: following the octave leap, the melody soars to a high G instead of lowering to D, and the subsequent line plunges down the scale instead of settling in puffs of turning figurations, as did the 1700 version.

1700: Example 5: Transcription of “The Ballad of King John and the Abbot of Canterbury,” mm.

1740: 7-9; transcription of “The Melody stolen … Death and the Cobler,” mm. 12-14.

Intervening printed versions reveal that these changes happened gradually, with the most significant change (to the form) taking hold in the late 1720s and early 1730s. Unfortunately, musical scores of the tune don’t turn up in written sources in the second half of the century, making it impossible to track further changes.

The written copies of the song represent only one mode by which the song was transmitted, for popular melodies like “Derry Down” also circulated orally. Such transmission, when songs were sung among groups of people and passed from voice to voice, was a prime mode by which a melody could be adjusted gradually. A person embellishes a bit here, goes up for a high note instead of down for a lower pitch. Like in a game of telephone, someone else hears it, likes it, and starts singing it that way. The trend catches on, and the next time the song is printed, these changes are notated in music and thus incorporated into the written record of the song. Members of a different community might see or hear the slightly different variant, recognizing it as “Derry Down,” noting that it deviated from what they were accustomed to, and perhaps adopting some of the innovations. Changes to the form of the song represent a more significant kind of innovation, and might have come about through the purposeful modification by a music compiler—but again, it is likely that the change was first made, either intentionally or unintentionally, by someone simply singing the tune. These changes suggest a robust and diverse performance tradition in the eighteenth century.

Having traced the early history of the tune, we can now speculate about what made “Derry Down” so popular for re-texting, and why writers turned to it when they needed a tune to express outrage over the XYZ Affair. Comparing the early and later versions of “Derry Down” shows that the tune became more buoyant, flippant even, by the mid-eighteenth century. Simply put, the changes to the melody made it more enticing and sensational. Furthermore, “Derry Down” dealt in something very valuable: gathered from the early versions, the tune was associated with righteous social and political critique, dressed in the trappings of parody and humor. The music itself supplemented that association, as the melody still churned with nostalgia in its minor mode and gentle lilt, conjuring romanticized images of a simpler time. Besides being memorable and fun to sing, the tune clashed deliciously with the sarcasm of the lyrics, like salt and vinegar.

An important musicological lesson inheres to this journey through “Derry Down’s” history: what we take as “the song” is in fact always changing, and the evidence we have to work with—written music—tells only one side of the story. For a different side we must both dig deeper into the music itself and explore the world it inhabited.

With the survey of “Derry Down’s” history and significance under our belts, we can turn back to “The Five Headed Monster,” one of the songs written in response to the XYZ Affair. What did Americans do with the song “The Five Headed Monster”? There is no evidence of performances—no descriptions of private music making, no newspaper accounts of singing the new political songs. Nevertheless, by analyzing the interaction of the text and the music and examining the materials in which the songs circulated, we can understand how “The Five Headed Monster” was used.

In vocal pieces, music can describe and exaggerate—or contradict—the message of the lyrics. This kind of text setting has a long history. Renaissance composer Josquin des Prez is renowned for his nuance in depicting and expressing the text by exercising keen compositional technique to underscore the concrete, and occasionally the connotative, meaning of the lyrics. Other composers could choose to be less subtle (if more entertaining). In a part-song by Italian Renaissance composer Claudio Monteverdi titled “Ardo avvampo,” voices shout “ardo, ardo” (“I burn, I burn”), sounding like a cry for help from a real fire, and gurgle “agua, agua, agua” in overlapping phrases, evoking the image of splashing water. Descriptive and expressive text setting lasted well into the twentieth century. Nineteenth-century German Romantic composer Franz Schubert wrote multi-song cycles in which the piano accompaniment is like a character in the story, murmuring its own account of the singer’s tale of love and loss. In popular music, Cole Porter’s “Every Time We Say Goodbye” switches from a major chord to a minor chord on the lyrics “there’s no love song finer, but how strange the change from major to minor,” and The Music Manprovides classic examples of descriptive text setting (think of the train scene in which traveling salesmen imitate the sound of the train).

Alas, “The Five Headed Monster” is no great example of expert and mellifluous text setting. The lyrics are humorous and clever (fig. 3), but despite being in the same basic meter as the “Derry Down” melody, they do not fit particularly well with the tune.

The melody cadences at the end of the second and fourth phrases, punctuating the lyrics at those points and emphasizing the rhymed couplets. In the first three verses, the phrases that receive this emphasis (capitalized for illustrative purpose) are: “…grand-mother EVE…vile Talley-RAND…heard from a FAR… are no QUAKERS…Butchers by TRADE… give us CASH!” Also, the octave leap in the third phrase draws attention to whatever word falls on the upper note. In the verses shown, this means the lyrics “under-STAND…look out for BREAKERS…count it but TRASH” all receive a musical punch.

With these various modes of musical emphasis, a tune can either seem to “agree” or “disagree” with the lyrics. In “The Five Headed Monster,” words that seem significant in the verse don’t always coincide with those points of musical emphasis, and the words that do fall on the cadences and the octave leap seem haphazard. Why should “breakers” and “far” receive emphasis? Very possibly the lyricist composed with only peripheral attention to what the music sounded like and little consideration of the practicalities of singing. Indeed, the ungainliness of the lyrics made the song cumbersome to sing.

The media in which the “The Five Headed Monster” circulated gives us further clues about how it was consumed. Sharing similarities with the field of book history, this line of inquiry asks questions about how songsters and newspapers were used. First, because political songs were disseminated in lightweight print media, they were eminently transportable and circulated readily. A songster might be slipped into a pocket, and a newspaper could easily be carried. Second, as relatively inexpensive and ultimately expendable items, the newspaper copies were regularly shared, and were often read in public spaces. An image comes into focus of informal gatherings, perhaps in taverns or coffee houses, at which the songs were shared, the lyrics skimmed or perused, read or sung aloud and laughed over. Songsters, more substantial and less disposable volumes, invited a more lingering attention to the song lyrics, perhaps in a domestic setting. Here, too, the songster was easily shared, brought to the house of a neighbor or friend for an evening of entertainment.

Finally, visual representations of music making in this time period would also afford clues about how songs like “The Five Headed Monster” were consumed; such pictures (if we have them) can be plumbed for factual information about musical practices, as well as interpreted as aesthetic objects in and of themselves. But even without pictures, we can conjure an image of how this political song circulated, spreading its message both literally through the lyrics and more subtly (but perhaps more persuasively) through the implied critique of the “Derry Down” tune.

The scantiness of the materials and the simplicity of the music might seem to discourage prolonged musicological attention to “The Five Headed Monster,” but the benefits of examining such a cultural micro-phenomenon are significant. For one thing, the intersection of music and politics is a topic of enduring interest. Music’s iconic role in an array of activist movements and at points of social upheaval, such as the Civil Rights Movement and more recently in Tahrir Square, are just a couple of instances that demonstrate why musicologists should care about musical politics, or political music. With “The Five Headed Monster,” and “Derry Down” in general, we gain a keener sense of how music was deployed for political ends—how music supported those goals, but could also sidetrack them. After all, even if the lyrics about the XYZ Affair referred only to France and the United States, Britain was a non-verbal third point of reference in the “Derry Down” contrafacta because of the tune’s English origins. Such songs perpetuated the complex cultural ties between the United States and Britain, while also illustrating the political machinations that took place in the early republic.

Forceful messages about collective self-fashioning are delivered in these sources, making them relevant to ongoing debates about music, culture, and identity. Every printed edition of “The Five Headed Monster” came with the expectation that readers knew the tune “Derry Down.” By taking for granted that the audiences had a shared repertory that included “Derry Down,” songster compilers and newspaper editors were implicitly pushing for a cohesive national culture that presumed English ancestry (or at least a familiarity with English music). A reader who didn’t know “Derry Down” was urged to learn how it sounded, or at least what it represented, because it was so prevalent in public culture. Leaving aside the question of whether the political sentiments expressed in the song lyrics were widely held, it is safe to say that “Derry Down” contrafacta put forth a kind of argument for cultural unity, even if that unity did not (or could not) really exist. This use of “Derry Down” commanded music as a common currency, and thus it was more prescriptive than descriptive of actual collective identity. In fact, in many cases tweaking British musical traditions to project American national identity was effective. After all, songs like “God Save the King” and “Yankee Doodle” were successfully assimilated into U.S. cultural identity by the early nineteenth century. Regardless of whether most Americans believed that the patriotic images inscribed in these songs pertained to their lives, the songs came to symbolize Americanness.

“Derry Down” did not achieve this iconic role, but it was certainly significant in its day; and examining it encourages us to ask far-reaching questions about the role of music in society—for instance, how aesthetic experiences simultaneously influence and are used to express national identity. It served as an abstract vehicle for the ideas and ideals with which political actors honed their distinct identities, taking advantage of the comical and satirical associations of the tune to vouch for specific critiques of powerful figures and foes. Yet the tune was not an empty vessel or a blank slate onto which messages could be chalked; rather, it was a palimpsest, with layers upon layers of meaning from past versions. By tracing the background and transatlantic dissemination and publication of “Derry Down,” and by delving into the music itself, we can begin to see how the contrafacta brought this legacy to bear on the ongoing negotiation of those identities and affiliations.

As we peer at history through the lens of music, however grimy the glass, we find that music to be an invaluable companion to historical research and a rewarding end in itself. Music scholars gobble up materials in their quest for insights into fundamental questions about music’s role in societies around the globe, and working with this material encourages us to keep asking about the larger meanings of music. How does music carry intelligible messages whose meanings individuals and groups can construe, either consciously or unconsciously, solely from the melodies? How do those meanings change over time? What does it mean to study a “piece of music” like “Derry Down” that itself is in flux, changing through oral and written transmission? These are philosophical questions about the essentially transient nature of music’s existence, and always deserve to be asked, even if they are never completely answered.

Further Reading

The version of “Yankee Doodle” criticizing the French is titled “Song, composed during the celebration of August 16th, 1799, holden [sic] in commemoration of Bennington battle…” The Echo: or Federal Songster (Brookfield, Mass., 1798): 15-17. “The Five Headed Monster; or, Talleyrand Dissected” appeared in the following sources: Commercial Advertiser (New York, N.Y.), August 4, 1798; The Newport Mercury (Newport, R.I.), August 14, 1798; Otsego Herald; or, Western Advertiser (Cooperstown, N.Y.), August 23, 1798; Greenfield Gazette (Greenfield, Mass.), August 25, 1798; Federal Galaxy (Brattleboro, Vt.), September 1, 1798; Impartial Herald (Newburyport, Mass.), September 11, 1798; The Federal Songster (New London, Conn., 1800): 10-12.

Several scholars have dedicated themselves to the mighty bibliographic task of assessing the vast quantity of American secular song in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. See Richard J. Wolfe, Early American Music Engraving and Printing: A History of Music Publishing in America From 1787 to 1825 with Commentary on Earlier and Later Practices (Urbana, Ill., 1980) and Oscar Sonneck, A Bibliography of Early Secular Music, 18th Century. Ed. William Treat Upton (New York, 1964). Online databases are invaluable resources. See Robert M. Keller, Kate Van Winkle Keller, Carolyn Rabson, Raoul F. Camus, and Susan Cifaldi, http://www.colonialdancing.org/Easmes/Index.htm and http://www.danceandmusicindexes.org/EASINew/Index.htm

Folksongs have long confounded scholars interested in tracing and categorizing traditional ballads such as “Derry Down.” For an overview of the history of the field, see Helen Myers, “British-American Folk Music,” in Helen Myers, ed. Ethnomusicology: Historical and Regional Studies (New York, 1993): 440-42. An excellent example of folk music scholarship is Charles Seeger, “Versions and Variants of the Tunes of ‘Barbara Allen'” in Studies in Musicology, 1935-1975 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, Calif., 1977). On the idea of “folk” music, see Matthew Gelbart, The Invention of “Folk Music” and “Art Music”: Emerging Categories From Ossian to Wagner (Cambridge, U.K. and New York, 2007). On the history of “Derry Down,” see William Chappell, Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time, vol. 1 (London, 1855-1859): 348-53; and Claude Simpson gives a thorough overview of the history of “Derry Down” in Britain in The British Broadside Ballad and its Music (New Brunswick, N.J., 1966): 172-6.

Introductions to music and musicology are numerous, but a classic text on engaged listening is Aaron Copland, What to Listen for in Music (New York, 1957), and Nicholas Cook provides valuable lessons in how to think critically about music in Music: a Very Short Introduction (Oxford and New York, 1998). Discussions of the methods, debates, and history of musicology can be found in the following books: Carl Dahlhaus, The Foundations of Music History, trans. J.B. Robinson (Cambridge, U.K., and New York, 1983); Joseph Kerman, Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology (Cambridge, Mass., 1986); Disciplining Music: Musicology and Its Canons. Ed. Katherine Bergeron and Philip V. Bohlman (Chicago and London, 1992). Richard Crawford provided an accessible and thoughtful discussion of musicology’s usefulness for historians in “A Historian’s Introduction to Early American Music,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 89 (1979): 261-298.

On the history of book consumption and print media in this period, see Robert A. Gross and Mary Kelley, eds. A History of the Book in America Volume 2: An Extensive Republic: Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation, 1790-1840 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2010) and Jeffrey L. Pasley, “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville, Va., 2001). An excellent survey of the multiple ways the United States negotiated its indebtedness to Britain during the period of the early republic is Kariann Akemi Yokota, Unbecoming British: How Revolutionary America Became a Postcolonial Nation (Oxford and New York, 2011).

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

Glenda Goodman teaches at the Colburn School in Los Angeles. She completed a PhD in historical musicology at Harvard University in May 2012, and her work on the impact of musical transatlanticism on early American communities has appeared in the William and Mary Quarterly and the Journal of the American Musicological Society. She is in the initial stages of a book tentatively titled Cultural Sovereignty and Music in the Early American Republic.