National Domesticity in the Early Republic: Washington, D.C.

Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

On November 20, 1791, Major Pierre L’Enfant, planner of the new capital city, ordered the demolition of a house against its owner’s will that stood in the way of what was to be New Jersey Avenue. The home’s owner, Daniel Carroll, belonged to one of the most prominent families who owned the land on which the capital was to be built. This showdown between private property and national government was not at all what the capital’s planners had envisioned. Indeed, L’Enfant and George Washington had hoped that the capital would help create the missing, personal relationship between the far-flung citizenry and the new nation. L’Enfant predicted that a beautiful capital would attract citizens to buy lots and settle there, making the nation’s capital their home. The capital would thus tie citizens emotionally and psychologically to the national government by giving them the chance to invest financially in its future.

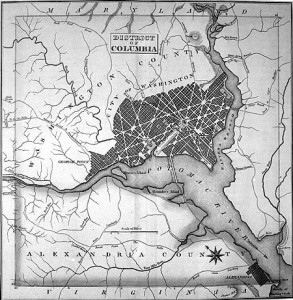

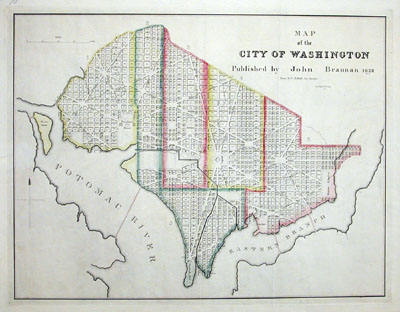

An early plan of Washington promoted the city’s real estate. It shows the capital’s two most famous features–the Capitol and the president’s house–as well as L’Enfant’s dynamic network of avenues (fig. 1). But just as importantly it shows the lots that citizens could buy; it was the development of these lots with fine homes and businesses that was to be as crucial to the success of the new capital as the splendor of its official buildings. George Washington had hoped that the capital would be a real city, a center of business and trade with many private citizens for residents, and not merely a government company town. An engraving of the city made in 1822 shows, through the dominating swell of the Potomac River, the optimism that the capital city would become the major water route inland (fig. 2). In George Washington’s mind, because the Potomac was “the center of the Union,” it would, due to “its extensive course through a rich and populous country become, in time, the grand Emporium of North America.” Attempts to make the river, which was cursed by shallows and shoals, into a viable trade route ultimately failed; politics and not trade was to be the city’s core.

The new capital did in fact inspire patriotic settlers. In 1799, John Tayloe III and his wife Anne Ogle bought land near the president’s house–Lot 8 on Square 170, bordered by New York Avenue and Eighteenth St., N.W. There they built an odd-shaped house to fit on their odd-shaped lot, one of the many such created by L’Enfant’s diagonal avenues. The Tayloe’s Octagon House, which still stands today, modeled the marriage of domestic and national life envisioned by Washington and L’Enfant. The Tayloes were one of Virginia’s most prominent families and Tayloe had run, unsuccessfully, for Congress. Their choice of the capital for their in-town winter residence signaled their support of the national government. They hired the architect of the Capitol, William Thornton, to build their private home. There they entertained members of official Washington, including Thornton and his wife, and their friend Harrison Otis Gray, congressman from Massachusetts. The Tayloes even fulfilled L’Enfant’s dream by making the capital their first, and not second, home, when some of the family eventually chose to live there year round. Best of all, the Tayloe home seems to have encouraged others to invest, as L’Enfant had hoped. By 1800 six houses stood on Square 170, three built of brick and three of wood.

The Tayloe’s model of national domesticity relied upon slavery, as did the development of the capital itself. Their home was supported by profits made on their large tobacco plantation, Mt. Airy, in Richmond County and on their other estates. They owned close to fifteen thousand acres of land and one thousand slaves. Each fall they brought as many as twelve slaves with them to Washington to serve their large family (which eventually included fifteen children) for the four months they remained in town. The house itself was built in part by slave labor, hired from local slaveholders. This was a common practice in the new capital; slaves provided the bulk of the labor to build the Capitol and other buildings, to clear the city’s avenues and streets, and to rebuild the city after its destruction during the War of 1812. While slave trading was relatively rare during the city’s first decade, by 1812 the capital was an important junction in the slave trade. It was not uncommon to see slaves in chains as they walked toward one of the holding pens in the city, or toward its docks to be shipped farther South. President James Madison’s secretary complained in 1809 of the “revolting sight” such “gangs of Negroes” presented in the streets of the capital of a nation that prided itself on its democracy and freedom.

Despite early successes in the development of the city, progress was frustratingly slow. Although there were periods of great building activity, such as after the War of 1812, by 1820 the government was still left with many of its lots unsold. The city’s population in 1820 was listed at 13,117, up from only 3,201 in 1800. In 1820 the city had 9,376 white residents, 1,796 free black residents, and 2,330 slaves. In 1800, slaves outnumbered free black residents five to one. The city’s growth remained tied to the growth of the national government. Artisans came to build the new city; lawyers, doctors, and storekeepers to attend to its community’s needs; servants and slaves to serve in its hotels, boardinghouses, and private homes.

The fact that everyone in the city helped to build or run the new government led to a new kind of domesticity that was literally shaped by national politics, although in ways L’Enfant and Washington could not have foreseen. The Supreme Court justices, for example, not only deliberated together, they lived together in boardinghouses, as did the members of Congress. The private homes of Washington’s official and nonofficial community naturally fostered a conversation about national politics and an accelerated schedule of entertainments and social calls that made the Washington home noticeably different than homes in other American cities. This national domesticity was crucial to the city and national government’s success. As historian Catherine Allgor has shown in her wonderful study of Washington’s “parlor politics,” it was one thing to draw up a Constitution with a set of laws by which the government would function, it was quite another to evolve a national political culture of manners and negotiating practices that would make that government work. The “inside the Beltway” mentality that we are now so familiar with did not exist; on the contrary, elected representatives were wary about wheeling and dealing on the national level. The more informal setting of the home became the site where such a culture could most naturally and even innocently evolve. We know that national policy is as often brokered around the Washington dinner table as it is in the House or Senate chamber. The logic of that custom was already becoming evident in the parlors and dining rooms of early Washington, D.C.

The ability of this national domesticity to foster political unity was demonstrated by the Supreme Court, whose members lived together in one boarding house until as late as 1845. Chief Justice John Marshall felt it was crucial the justices live together, without their wives, in order to promote a collegiality that he predicted would lead to unanimous decisions. Unanimity would secure the Court’s authority, Marshall believed; divided opinions would make its decisions appear arbitrary. The Marshall Court succeeded in handing down one unanimous decision after another, a feat that historians trace to the fraternity created by their “communal life.” Justice Joseph Story described the harmony he enjoyed with his “brethren”: “[We] live in the most frank and unaffected intimacy . . . united as one, with a mutual esteem which makes even the labors of jurisprudence light . . . we moot every question as we proceed, and familiar conferences at our lodgings often come to a very quick and, I trust, a very accurate opinion, in a few hours.” In this way, the Supreme Court’s all-male home helped to establish the authority of the new national government.

Because Congress, like the Supreme Court, only met during the winter months, congressmen also lived in boarding houses rather than rent or build a house of their own. Congressmen tended to live with others from their region, and while this nurtured political unity on the regional level, James Sterling Young has shown how, on the national level, it nearly broke the nation apart. The boardinghouse communities became the congressmen’s “family.” Some houses included the wives of congressmen, but several were, aside from the wives, daughters, and servants who helped run them, all male. Daniel Webster described congressional life in early Washington as one of “unvarying masculinity.” Members not only ate together but even senators “slept two to a room.” They lived and dined like “scholars in a college, or monks in a monastery.” For some, such arrangements offered a pleasant change from home life with women: According to one congressman, “Members ‘threw off their coats and removed their shoes at pleasure. The formalities and observances of society were not only disregarded, but condemned as interferences with the liberty of person and freedom of speech and action.’” This fraternity continued onto the House and Senate chambers’ floors, so that during the first four administrations in Washington, congressmen tended to vote not according to their party but their boarding house. When one congressman failed to vote with his messmates another congressman complained, “We let him . . . sit at the same table with us, but we do not speak to him . . . He has betrayed those with whom he broke bread.” James Sterling Young attributes this startling herd mentality to the antipower culture of the era, an era still colored by the hatred of monarchy that fueled the American and French Revolutions. That such feelings infused boarding house culture is suggested by the fact that Vice President Thomas Jefferson not only refused to take the place of honor closest to the fire at his Capitol Hill boarding house, but instead took the seat furthest away. Congressmen insisted they served reluctantly, from a sense of duty. They feared being accused of acting independently and not according to their constituents’ will. The whole idea of an individual man or group vying for leadership to organize votes was distasteful. Congressional fraternities offered a refuge where they could cope with decision making on a national level. The boarding house system continued, even after political parties gained much more influence, up until the Civil War.

The fledgling quality of a national political network was registered in the residential patterns of the early capital and even in its very streets. The city’s neighborhoods were formed not according to economic class or race, but branches of the government. Congressional boardinghouses clustered around the Capitol, while the individual residences of the executive community, and all the workers and servants associated with it, clustered around the president’s house. There was not much visiting between the two neighborhoods since the legislature and the executive still tended to eye each other suspiciously. Pennsylvania Avenue, the main thoroughfare which connected these two communities, registered and enforced their estrangement. Pennsylvania Avenue was a terrible road: carriages turned over and their wheels got stuck in its mud. Congress could have voted more funds to improve the avenue, but didn’t, which suggests congressional ambivalence not simply toward the nation, but toward its capital city, too. The avenue remained a dirt road until 1832.

Stymied by such political antipathy, it was left to Washington women to show the men the importance of circulation. The paying and receiving of social calls was one of the main jobs of affluent women and it was only a matter of time before political negotiations found a more natural place in the drawing rooms and parlors of Washington’s boarding houses and private residences. Women such as Louisa Catherine Adams, Dolley Madison, Hannah Gallatin, and Floride Calhoun all used their “female network” of influence toward political ends, whether it be to support a particular piece of legislation, secure a government post for a relative or friend, or to improve the city through the creation of a hospital or orphanage. Indeed, Catherine Allgor credits Margaret Bayard Smith with being the very first “Washington insider.”

Smith, wife of the editor of the newspaper the National Intelligencer, established a particularly powerful circle of influence. Through it she secured a government position for the son-in-law of Martha Jefferson Randolph, only living daughter of Thomas Jefferson, whose family by 1828 was nearly impoverished. Smith had been a staunch supporter of Jefferson and thus her lobbying on his daughter’s behalf was not only a compassionate but a political act. It was this fuzziness between the personal and the political that gave women a wider scope than men. Just as the national culture was still antipower, it was also antipatronage, but women were able to avoid this charge. Since women weren’t “in” politics, they could claim to work from purer motives of affection and compassion, and this gave them leverage and innocence that men might lack. Another attempt by Smith to help her brother-in-law become a Supreme Court justice shows how this “parlor politics” worked. Smith tells in a letter how she called upon the wife of a man whose influence Smith needed to court. Her friend, “with her usual kindness immediately asked me to stay to dinner, which invitation I accepted, having found gentlemen more good humored and accessible at the dinner table than when alone.” On another occasion Smith managed to get a young Mr. Ward a spot on the sofa next to Representative Henry Clay. The two men enjoyed their conversation, a correspondence ensued, and Mr. Ward had a valuable ally in Washington. Through their social rituals, Washington’s women created a trust and informality that forged the personal networks so crucial to government. As the capital’s first and largest group of lobbyists, Washington women helped pave the way for the rise of first the patronage and then the party system, organizations which would make it less necessary, and hence less common, for women to play such an active political role.

In addition to being more engaged in political debate, white affluent women enjoyed a greater degree of personal freedom in Washington than in other American cities. It was more acceptable for women to go about the city unaccompanied by men. They went to the Capitol in order to watch Congress or the Supreme Court in session (three hundred women crammed into the galleries, and even onto the Senate floor, to hear the Webster-Hayne debates). Washington parties were often very crowded and women had to stand. For Margaret Bayard Smith this simple fact gave women more social mobility, since they did not have to sit, as was the custom, and wait for men to come to them. While Washington society was still structured rather rigidly according to class, a “respectable” woman could take advantage of the fact that in Washington one could be “decently aggressive” and push her case. The fact that the president’s house was still the people’s house made Washington’s official and nonofficial homes more open than those of other American cities.

Little is known about daily life for Washington’s black population. African Americans did enjoy a slightly greater degree of freedom in the nation’s capital. They could visit the monumental buildings and the men could watch the congressional debates. Their behavior was restricted, as in other southern cities, but less severely. The capital had a black code that set fines or jail sentences for any person found loitering after curfew, attending a meeting, gambling, drinking, or caught without a certificate with the name of their master or proof they were free. These fines and laws became more stringent by 1820.

On the whole, Washington’s black and white communities lived side by side, intertwined yet separate. At the Tayloe’s Octagon House, a servants’ stair helped keep servants close at hand and yet out of sight; the butler had a closet by the front door where he could hide until someone came to the house. Washington’s slaves tended to live in a service wing at the back of the house, or in a free-standing structure at the back of the yard. Thus a spectrum of Washington society might live on any one block: the block’s outer perimeter would include a mixture of fine and modest homes, some owned by prosperous free blacks, while its interior contained slave quarters. One of Washington’s most prominent black families itself encompassed this social spectrum. William Syphax, a free man, lived with his wife and daughters, whose freedom he purchased, in their own house on the corner of Seventeenth and P Streets, N.W., while his son was a slave living in the quarters at Arlington House, home of Martha Washington’s grandson, George Washington Parke Custis. Custis’s only child, Mary, would inherit the house, where she would live with her future husband, Robert E. Lee.

The confrontation between L’Enfant and Daniel Carroll came in large part because L’Enfant was out of step with the political culture in America, a culture that did not share L’Enfant’s grand vision for the national government and could not tolerate his autocratic style. L’Enfant’s decision to raze Carroll’s house, with its insistence upon national circulation over local sovereignty, was only one, if perhaps the most egregious, of the acts that led to his dismissal. He haunted the capital after that, badgering Congress for the money he believed he was still owed for the planning of the capital. In the last years of his life, he was all but destitute; he lived the final year of his life, ironically, at the home of Daniel Carroll’s daughter, Eleanor Carroll Digges. Brought at last into Washington’s domestic fold, he died in her house in 1825 and was buried in the Carroll-Digges family plot. In 1909 his remains were moved to the Arlington National Cemetery to a grave site overlooking the capital–a city whose streets he had planned, but whose domestic life had evolved along its own political paths.

Indeed Arlington National Cemetery was created during the Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House. Mary Custis and Robert E. Lee’s abandoned home was thus surrounded by the graves of soldiers who died in the war. There, on the estate, the federal government also established a freedman’s village, a model community where freedmen could farm and live on their own land as an inspiration to the national community. As such Arlington House offers perhaps only an extreme example of the strange tangle of domesticity and national politics so central to the history of Washington, D.C.

Further Reading:

I am indebted to the following studies of Washington’s early history. Here, I list specific pages from each work that I have quoted or paraphrased above. Catherine Allgor, Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government (Charlottesville, Va., 2000), 118, 136-38; H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre Charles L’Enfant (New York, 1970), 268-69, 288; Barbara Carson, Ambitious Appetites: Dining, Behavior, and Patterns of Consumption in Federal Washington (Washington, D.C., 1990), 165-66; Sandra Fitzpatrick and Maria R. Goodwin, The Guide to Black Washington (New York, 1990), 239-41; Constance McLaughlin Green, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the National Capitol (Princeton, N.J., 1967), 15-33; George McCue , The Octagon: Being an Account of a Famous Washington Residence: Its Great Years, Decline & Restoration (Washington, D.C., 1976), 23-26, 41, 57; John W. Reps, Washington on View (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1991), 54; Orlando Ridout V, Building the Octagon (Washington, D.C., 1989), 84, 98, 110; Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer of a Nation (New York, 1996), 286-87; John Michael Vlach, “Evidence of Slave Housing in Washington,” Washington History (Fall/Winter 1993-94): 64-74; George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, ed. by John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington, D.C., 1939), 31:438; James Sterling Young, The Washington Community, 1800-1828 (New York, 1966), 101, 105, 122-24, 250.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Sarah Luria is an assistant professor in the English department at the College of the Holy Cross. She is currently completing a book manuscript entitled Capital Letters and Spaces: How Writers Helped Build Washington, D.C.