Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

In 1608 the Castillian-born adventurer Juan Martinez de Montoya, a man described as “tall, of good feature, blackbearded,” reported that he had “made a settlement at Santa Fe.” The place he called Santa Fe was a beautiful little valley with a small river flowing through it, beneath the mountains a few miles east of the river named the Rio Grande. It grew into the capital of the province of New Mexico, and for more than one hundred and sixty years, until Monterey was established in California in the late eighteenth century, Santa Fe was the northernmost capital of a Spanish province in the New World. It was the second permanent Spanish colony within the present United States–San Augustine, Florida, founded in 1565, was the first–and was established within a year of the settling of Jamestown, the first permanent east coast English colony, in 1607. It was the first permanent European colony in the American west.

At the time Santa Fe was founded, New Mexico was floundering. Juan de Oñate, the proprietor and military commander of the colony, had established New Mexico in 1598, with his headquarters at the pueblo of San Gabriel, just west across the Rio Grande from the still-existing pueblo of San Juan. Ten years later, Oñate was going broke because he had not discovered the legendary gold mines of Gran Quivira, and a faction led by his secretary of war and government, Juan Martinez de Montoya, was lobbying successfully with the viceroy of New Spain in Mexico City for his arrest and replacement. Martinez de Montoya was forty years old when he arrived in New Mexico as a captain in the reinforcements sent to the new colony.

One of the strangest things about Juan Martinez de Montoya’s most important act–the founding of Santa Fe–is that it is shrouded in mystery. For most of the twentieth century, the actual year of the founding of Santa Fe was a matter of historical speculation, and the name of its founder, Juan Martinez de Montoya, has only recently been accepted by scholars.

The uncertainties about the early years of Santa Fe are entangled in the history of New Mexico itself. The region along the Rio Grande that became the core of New Mexico was first explored by Coronado in 1540-42, and for a long time it was a tradition (and still is, among some of the more irresponsible tour guides) that Coronado had himself placed a small Spanish settlement in an Indian pueblo at the place called Santa Fe. Others argued that if Coronado did not establish Santa Fe, then Antonio de Espejo, an explorer who visited the future location of the town in 1583, must have done so. These stories, unsupported by any historical evidence, date to the 1880s, when they were created by a rather unscrupulous group of Santa Fe businessmen who were promoting a bogus three-hundred-fiftieth (or perhaps three-hundredth) anniversary of the founding of Santa Fe in an effort to boost tourism to the city.

But what began as a fraud became almost unassailable history, since it was nearly impossible for historians to find evidence to disprove this specious date because virtually all manuscripts–public, private, and religious–recording the history of the province were destroyed during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, when most of the pueblo Indians of New Mexico rose up against the Spanish occupiers and drove them out of the province for a period of twelve years.

The great date debate, then, is based on rather slender records, the few that Spanish authorities had sent out of New Mexico before the revolt. At first, historians were sure that Santa Fe had been founded sometime early in the 1600s, and they generally agreed on a date of “about 1605” as most likely correct. The well-respected historian Frederick Hodge presented a succinct summary of the argument in favor of this date in 1913–but the same year, the equally respected historian Lansing Bloom published an equally firm statement that the founding must have been after 1609, and possibly as late as 1617.

Sometime during the 1920s, the problem seemed to be cleared up with the discovery of a set of instructions from the viceroy of New Spain to don Pedro de Peralta, appointed the new governor of New Mexico in 1608. Among these instructions was a clear order to create the Villa de Santa Fe as the capital of the province as soon as Peralta arrived there. Since Peralta must have reached New Mexico in the spring of 1610, most historians concluded that Bloom had been right in his claim that Santa Fe had been established sometime soon after 1609, and 1610 became the accepted date for the founding of Santa Fe.

But in 1944, the man who had emerged as the leading historian of New Mexico, France V. Scholes, published a short note that he had examined a file of documents owned by Maggs Brothers of London, dealers in antiquities. This file contained, among other things, a number of certified copies of documents recording the activities of Juan Martinez de Montoya in New Mexico. Little was known about Martinez, other than that the viceroy had appointed him governor when Juan de Oñate resigned in 1607, but the advisory council of the colony refused to accept him, and made Oñate’s son, Cristobál, the acting governor in his place. Scholes reviewed the testimony in the file, and to his surprise found a specific statement that at some point in the period from mid-1607 to mid-1608, probably in the first months of 1608, Martinez had established a “plaza de Santa Fe,” a private settlement or town of Santa Fe. During this same period, Martinez became disgusted with the untenable political situation in New Mexico, and decided to leave the new colony and return to Mexico. He did so in late 1608.

The existence of these documents, although discussed by Scholes in 1944, was quickly forgotten during the tensions of the war years, and noticed only as a curiosity afterwards, until Dr. Thomas Chavez, director of the Governor’s Palace Museum, decided to see if there was anything more to the story as presented by Scholes. In 1994, Chavez contacted Maggs Brothers of London, and found that they still held the documents. The state of New Mexico purchased them and they are now a permanent part of the collection of the Governor’s Palace.

Juan de Oñate established New Mexico as an entrepreneurial colony, one that was intended to make him a profit. The presence of the Pueblo Indians gave the colony a good financial basis, because Oñate was given the privilege of dividing the products of their pueblos among the military leaders of the colony, in an arrangement called encomienda. This gave the leaders an income that allowed them to each support a troop of armed militiamen and their horses, which would provide the protection of the new colony. Oñate expected to find the so-far-unlocated golden cities of Gran Quivira, and to make a huge profit from taking this gold and tracking down the mines from which it came. “I trust in God that I shall give your majesty a new world, greater than New Spain,” he wrote to the viceroy. Such success had happened before in the eighty years between the conquest of Mexico and the conquest of New Mexico–Oñate confidently expected it to happen again, with himself and his followers as beneficiaries.

Oñate proceeded to break a number of the Laws of the Indies in his efforts to regain the expenses he had spent in order to establish the colony and in his efforts to make the big Gran Quivira gold strike. Establishing a viable colony, getting farming and ranching established, and setting the religious conversion program of the Franciscans on a sound basis were all secondary concerns. Ultimately this led to dissension and factionalism. The colony divided between the militarists, who were convinced that a little more squeezing, a few more expeditions against surrounding tribes, would reveal the great quantities of gold that Coronado had said the Indians of the area had told him about, and the settlers, who wanted to establish their farms and ranches, set up a reasonable working relationship with the pueblos, and get the colony onto a sound economic footing. A trade in hides, cattle, sheep, and salt to the silver mining towns to the south could produce a dependable income.

Martinez was apparently a key member of the settler faction, and an opponent of the militaristic approach of Oñate and his officers. But Oñate, as poblador, as the man who created the colony, was allowed to set up the government, so all the political positions of any power in Oñate’s capital at San Gabriel were occupied by his faction.

Most of these men lived in houses converted from the rooms of the pueblo of San Gabriel–the Indian families who had lived here had moved to San Juan when Oñate took over the pueblo. Dissatisfaction with Oñate’s decisions, with his favoritism for his ruling clique, and with his failure to achieve anything like a dependable civil establishment led to a mutiny among the nonmilitarist settlers, and some actually fled the colony and returned to Mexico, including some of the Franciscan priests. Father Juan de Escalona reported that “the entire army, in a body, resolved to move to some other place where it could find relief for its wants.” Influential members of the settlers’ faction, probably led by Martinez, sent complaints about the situation to the viceroy. The viceroy wrote to the king that “I cannot help but inform your majesty that this conquest is becoming a fairy tale.” The king determined that Oñate had far overstepped his privileges, and prepared to have him arrested and brought to Mexico City. Oñate, apparently with friends in the capital, seems to have heard of this impending order, and resigned the governorship in August 1607. When the viceroy was notified of Oñate’s move, he then sent an order to New Mexico appointing Martinez de Montoya acting governor in place of Oñate. The events clearly imply that Martinez was a member of and probably the leader of the pro-civil government, pro-development, anti-military, anti-conquest, and anti-exploitation faction. The ruling council refused to accept Martinez, saying that he was “not a soldier,” that he was not of the militarist faction, and appointed Oñate’s son, Cristobál, instead.

It was apparently the same settler faction that in 1608 petitioned for the establishment of a new capital of New Mexico away from the Indian pueblo of San Gabriel. The petition was sent to the viceroy on the wagon train of August 1608, coincidentally the same wagon train in which Martinez de Montoya returned to Mexico City. This wagon train arrived in Mexico City in December 1608. A copy of the petition no longer survives, but King Philip’s response in early 1609 mentioned that “the Spaniards and the friars residing [in New Mexico] were planning to establish a villa.”

The information that arrived by this wagon train, including that brought by Martinez himself, convinced the king to appoint a new governor, Pedro de Peralta, for the province of New Mexico, and ordered him “to settle or found the villa in question,” to be the capital of the province. When Peralta arrived in New Mexico, he ended the entrepreneurial colony and established a royal colony instead. He applied the order to establish a villa to Martinez’s settlement of Santa Fe, raising it from a plaza, or village, to a villa, or town. In other words, the king’s orders to Peralta did not establish the town of Santa Fe, but simply elevated the already-existing settlement to that rank.

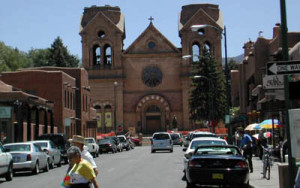

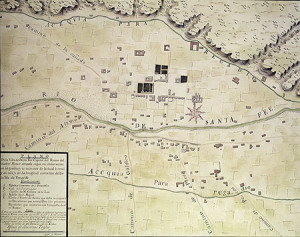

The town had been established on the north bank of the Santa Fe River, near the head of its valley. Several springs and marshes were scattered along this bank, and the little town was fitted onto a dry area between these watery areas. It appears that the town plaza and primary streets were laid out at the time of the establishment of the settlement, and the plan was developed farther when the place became the official capital two years later. The lot for the town church was established at the east end of the plaza, and the north side of the plaza was selected as the site for the governor’s residence. Unfortunately, the Pueblo Revolt destroyed all property records and any maps of the town during the period from its establishment about 1608 to 1680. The earliest surviving map was drawn in 1767, after many changes had altered the details of the town plan–but the 1767 map probably gives a good impression of the general layout and appearance of the town. Santa Fe was laid out as a series of blocks around a plaza, with the government buildings on its north side. Originally, the plaza was probably a long, rectangular area extending eastward to the front of the parish church, but later inbuilding filled part of this area with houses. Remarks in documents of the 1600s name at least one street, San Francisco Street, which was probably the same street with that name today, passing along the south side of the much-reduced town plaza.

The town served as the capital of the Province of New Mexico until the revolt in 1680, and then was reestablished as the capital of the reconquered province in 1692. It continued in this position through the Mexican period until it was captured by American forces in 1846, during the Mexican War, and became the capital of the state of New Mexico when it entered the Union in 1912. The Spanish considered the province to be “remote beyond compare,” harshly cold even in the summer, and with such a short growing season that it was difficult to raise their usual crops. Located in a high desert climate at seven thousand feet, Santa Fe receives only about ten inches of rain a year, quite unlike most of the provinces farther south.

Ultimately, Santa Fe became the capital of a province of missions, ranchers, and farmers. Oñate’s expectations of a great gold strike never came true–the value in the colony was in its land, its people, and the supplies it could send to the great silver strikes in the Santa Barbara and Parral areas to the south. This was what Juan Martinez de Montoya and his settler faction had argued for, and although he was forced out of the colony, his vision for its future development proved to be correct. For the rest of its colonial and Mexican history, New Mexico remained a land of farmers and herders, trading supplies to the silver mines to the south.

Further Reading: More about the story of Santa Fe, and the days of the earliest exploration of the American Southwest, can be found in John Kessell, Spain in the Southwest: A Narrative History of Colonial New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and California (Norman, 2002), and David Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven, 1992).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

James E. Ivey is a research historian for the history program of the Intermountain Cultural Resource Center of the Intermountain Regional Office, National Park Service, in Santa Fe. An archeologist and architectural historian, his work has centered on missions, presidios, frontier forts, ranches, settlements, and industrial sites from Texas to California.