When Rip Van Winkle stumbled, gray-bearded and confused, into his Hudson River town, one of the first indications that his little village had changed dramatically was a tavern sign. “He recognized on the sign . . . the ruby face of King George, under which he had smoked so many a peaceful pipe; but even this was singularly metamorphosed. The red coat was changed for one of blue and buff, a sword was held in the hand instead of a scepter, the head was decorated with a cocked hat, and underneath was painted in large characters, GENERAL WASHINGTON.” Washington Irving’s choice of a tavern sign to symbolize the social and political transformation of Van Winkle’s village accurately reflected the central place these objects had in the streetscapes of colonial towns. Tavern signs advertised the availability of food, drink, and lodging, but they were also meant to entertain and, sometimes, to broadcast the tavern owner’s political sympathies. The use of tavern signs to display political alliances accelerated during and after the Revolution. But in Dedham, Massachusetts, in the late 1740s, tavern owner, almanac writer, physician, and common lawyer Nathaniel Ames used his sign to skewer five of the province’s most powerful politicians: the justices sitting on the Superior Court of Judicature, Massachusetts’ highest court of law.

Nathaniel Ames was well known in provincial Massachusetts–and perhaps all of New England–as the publisher of the humorous, satirical, somewhat useful, and enormously popular Ames’ Almanack (fig. 1). Ames, born in 1708, began publishing the periodical when he was just eighteen years old and living in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Around 1730 he moved to Dedham, approximately twelve miles southwest of Boston, and continued to publish the almanac until he died in 1764. His sharp-tongued commentary on Massachusetts’ politics, religion, and social life made Ames’ Almanack a bestseller. By the 1760s, according to one estimate, he was selling almost sixty thousand volumes a year.

In addition to almanac writing Ames practiced medicine. In court documents he called himself a “physician” and he regularly visited patients, dispensing medicine, performing surgeries, and giving advice. Most likely he learned his craft from his father, “Captain” Nathaniel Ames (1677-1736) of Bridgewater who was a mathematician, astronomer, and “physician,” but books also played a role in the younger doctor’s practice. Nathaniel II’s estate inventory lists approximately twenty-eight medical volumes including “Turner’s Surgery” and “Keil’s Anatomy.”

His move to Dedham brought Ames closer to the intellectual ferment of Boston and Cambridge, but it also, ultimately, brought him an economically and politically strategic position as a tavern keeper. In 1735 Ames married Mary Fisher, the daughter of Captain Joshua Fisher, who had died in 1730. Captain Fisher was the master of a Dedham ordinary (as taverns were called) that had been in business perhaps as early as 1658. Taverns were key sites for economic, social, and political activities in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New England towns (figs. 2, 3). They served up food, drink, lodging, entertainment, news, and gossip to both townspeople and travelers. Most significant, they were vitally important public spaces–places to conduct business and communicate information. In the county seat, or “shire” towns, the courts of law often sat in taverns or in meeting houses until the shift to purpose-built courthouses at the end of the eighteenth century. In all towns, local justices of the peace held “justice’s courts” for adjudicating minor offenses and disputes in tavern rooms. As a result of their proximity to legal proceedings, many tavern keepers worked as common lawyers in addition to running their hostels. Much to the chagrin of professionalizing lawyers who worked to root out these “pettifoggers,” or untrained advocates, tavern keepers’ physical location at the center of business and legal activity poised them perfectly for representing clients at justices’ courts, filing writs and appeals, and keeping track of fees and accounts. This confluence of functions–mercantile activities, judicial proceedings, information exchanges–made tavern rooms significant sites for the creation and manipulation of public opinion, and blessed tavern keepers with lucrative opportunities for participating in a wide variety of social, economic, legal, and political exchanges.

Nathaniel Ames was no different. He worked as a common lawyer in addition to publishing almanacs, tending the sick, and running his late father-in-law’s tavern with his wife and mother-in-law. Whether owing to his close reading of the law or a sheer, dogged determination to win his causes, he was somewhat successful as a common lawyer. His estate inventory taken in 1765 itemized a collection of law books valued almost as much as his medical treatises. Notable volumes include “Coke’s Institutes Abriged” and Giles Jacobs’s, The Law Dictionary.

Ames needed these books because he seemed constitutionally unable to stay out of court or to accept an unfavorable ruling. For instance, in 1735 Ames became embroiled in a dispute with housewright John Fisher of the neighboring town of Needham over alterations to Ames’s dwelling house. The contract for the work included a clause requiring Fisher to pay Ames £300 if the job wasn’t finished in three months. Unhappy with the result, Ames sued Fisher and when the court ruled against him, Ames appealed to the Superior Court of Judicature only to lose again. In February 1740, Ames went back to the Superior Court arguing that the “judgment is wrong and erroneous and ought to be reversed.” The court continued the case from term to term, perhaps hoping that the disputants would settle it between themselves, but finally referred the case to arbitrators who awarded Ames £98 in August of 1740. Five years and four lawsuits later, Ames had won his case but less than one-third of his damages.

During this time a decidedly more complex legal issue began to occupy Ames’s court calendar. His wife Mary Fisher was the beneficiary of her father’s estate, which included the tavern and various pieces of property in Dedham. In his 1729 will Joshua Fisher gave his wife Hannah a life estate in the property that would go to Mary at the time of Hannah’s death or remarriage. Mary and Nathaniel had a son named Fisher in October 1737, but Mary died two weeks after giving birth and Fisher died the following September. After his son’s death, the probate court assigned Nathaniel as administrator and sole beneficiary of the infant’s estate, which, presumably, included all the property baby Fisher had inherited from his grandfather through his mother. Mary’s relatives, however, did not agree that the property could ascend back to Nathaniel, but, rather, that it should descend to the “next of kin to Fisher”–his cousins and their children.

Of course, during her lifetime, Ames’s mother-in-law Hannah Fisher controlled the estate, but clearly trouble was brewing. In September 1744 Ames complained to the criminal court that his late wife’s sister, Judith (Fisher) Simpson, had assaulted him and “took his hat worth 20 shillings and his wigg worth forty shillings from off his . . . head and threw his said hat down upon the ground and carried away his said wig.” The criminal complaint was dismissed but Ames sued Simpson for damages to the hat and Simpson’s husband countersued Ames for damaging his wife’s reputation. Although Ames won both cases, Simpson appealed to the Superior Court, which referred the case to arbitrators who found all the suits “vexatious and litigious” and ordered the court costs to be split between the parties and the “wigg to be returned.”

In December 1744 Hannah Fisher died and the battle over the Fisher estate was joined in earnest. In July 1745 a scuffle broke out in one of the hay fields. John Simpson, Benjamin Gay (husband of Mary’s sister Hannah), and Samuel Richards (husband of Mary’s late sister Rebecca) charged that Ames had stolen hay from their field. Ames quickly countersued arguing that it was his meadow and Richards, Gay, and others “did enter the close of Nathaniel Ames . . . and assaulted one Catoe a Negroe of said Ames.” The court ruled in favor of Ames, but in the meantime Benjamin Gay and his wife had taken physical possession of a large portion of the estate requiring Ames to sue again to recover his property and reestablish his claim to the Fisher estate.

The arguments in Ames v. Gay, et al. rested on a tension between English common law and Massachusetts Province Laws. As historian Carole Shammas explains, “In the common law, only descendants could inherit, not ancestors, and heirs had to be of the full blood. A father or grandfather could not take possession of the property.” On these common law principles rested the argument that the estate of Captain Joshua Fisher should descend to Mary’s sisters’ children–the Richards, Gay, and Simpson families. Nathaniel Ames, however, pointed to a Massachusetts Province Law of 1692 entitled “An Act for the Setling [sic] and Distribution of the Estates of Intestates,” which stated that estates should pass equally to “every [one] of the next of kin of the intestate, in equal degree . . . and if there be no wife all shall be distributed among the children; and if no child, to the next of kin to the intestate in equal degree . . . and in no other manner whatsoever.” Ames was certain that this law applied to the Fisher estate–that after baby Fisher’s untimely death he was the “next of kin.”

The case Ames v. Gay, et al. commenced in the Suffolk County Court during the October 1746 term. This court found for Gay and awarded him court costs, an action that had the effect of overturning the probate judge’s decision and awarding the entire estate to Gay. Ames appealed to the Superior Court the following February, when the court found again for Gay, confirmed the judgment, and charged the costs of court to Ames. There the dispute stood until August 1748, when Ames appealed again to the SCJ for “recovering judgment against the said Benj. Gay for restitution of the [court] costs and for possession of the premises demanded in the original writ.” The Superior Court jury, unclear as to the point of law, referred the case back to the justices who, fortunately for Ames, ruled in August 1749 that the Province Laws took precedent over the common law. They restored the Fisher estate to the almanac author.

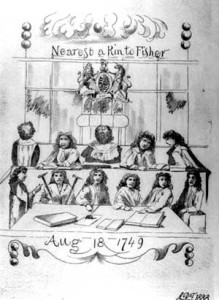

The verdict, however, was not unanimous. Ames was clearly stung by the dissent of two justices: Chief Justice Paul Dudley and Justice Benjamin Lynde, a newcomer to the bench. As the victor, Ames had no recourse at the bar. But he did have recourse in the court of public opinion. At his tavern in Dedham, Ames put up a signboard that depicted the justices of the Superior Court of Judicature and the participants in Ames v. Gay. Although the object itself does not survive, a pencil sketch of the sign among the Ames Family Papers clearly shows Ames’s intent (figs. 4, 5). At the bottom of the sketch, a note reads “Sir, I wish I could have some talk on the above subject, being the bearer waits for an answer, shall only observe Mr. Greenwood thinks that can not be done under £40.”

In its overall design and dimensions the sign was typical of eighteenth-century Anglo-American commercial advertisements: rectangular in form with a carved top and bottom crest rail and two turned dowels supporting wood planks on which the image was painted (fig. 6).

Atypical, though, was the detailed scene of the court chamber in the Boston Town House (now the Old State House). The five Justices sit on a single bench beneath the wooden carved royal crest–a symbol of their authority as the king’s representatives (fig. 7).

The two dissenting justices, Benjamin Lynde at the far left and Paul Dudley occupying the chief justice’s position at the center of the bench, have their backs to the courtroom and, by analogy, their backs to the laws of Massachusetts. The three concurring justices, from left to right Richard Saltonstall, Stephen Sewall, and John Cushing, are facing forward consulting open books. The identity of the figures in the bench below the justices is a little more speculative, but presumably they represent participants in the trial. At the far left the defendant Benjamin Gay stands before a closed book labeled “Province Laws” and gestures toward the high sheriff holding the traditional emblems of office, his staves. To the right of the sheriff is the clerk of the court pointing toward the quill pen with which he will record the court proceedings. The figure to the far right is perhaps Ames himself with his lawyers pointing toward the books in which the applicable Province Law appears. At the top of the sign appears the legend “Nearest a Kin to Fisher” and at the bottom, the date “Aug. 18 1749.”

Ames’s sign might seem tame as political satire, but to Dudley, Lynde, and the other justices it was a severe affront. They ordered the sheriff to go to Dedham, take down the sign, and bring it back to the Boston court. No record of the sheriff’s findings is extant, but early Dedham historians assert that Ames was able to remove the sign before the sheriff arrived. The preliminary sketch and the court’s order for the sign’s removal are the only surviving pieces of evidence for Ames’s clever contempt of judicial authority.

The scene depicted on the signboard conveyed multiple meanings–none of them flattering to the court–and certainly Ames, his wit honed by almanac writing, crafted each subtle jibe. The sign celebrates his victory, but also pokes fun at the court, which presumably needed lengthy deliberations in order to arrive at the conclusion that Ames was his own son’s nearest kin.

His portrayal of Paul Dudley with his back to the courtroom is particularly insulting since a chief justice was traditionally the supreme authority over sessions of the Supreme Judicial Court. Ames must have relished his depiction of the imperious chief justice. The son of Joseph Dudley, who had served as governor from 1702-15, Paul Dudley received his legal training at one of the English Inns of Court. He was only the second Superior Court justice to have trained at the Inns of Court and been admitted to the bar. The first justice to receive formal legal training was Benjamin Lynde Sr., the father of Dudley’s rear-facing bench mate. Ames’s tavern sign, then, plays on the tension between lawyers with formal legal training like Dudley, and village tavern keepers and pettifoggers like Ames himself. The self-taught Ames sits assuredly in front of the law of the land, easily reading from an open book, while Chief Justice Dudley turns his back. Last, Ames surely was highlighting Dudley’s famous arrogance and royalist allegiances. When Dudley’s father arrived as governor in 1702 he brought with him a warrant from Queen Anne appointing Paul as the province’s attorney general–a prerogative hitherto claimed by the colony’s General Court. The Dudleys’ administration was thus dogged by charges of nepotism and accusations that they were trying to undermine the colonists’ liberties. The image of Paul Dudley turning his back on the Province Laws raised again the question of his loyalty to Massachusetts and its legal traditions.

Ames narrowly escaped the Superior Court’s wrath and managed to win his case in a court of law and, perhaps, in Dedham’s court of public opinion. He recognized that taverns, like almanacs, presented opportunities for contesting traditional authority by thinly cloaking that critique in humor or entertainment. His tavern sign, though ultimately ephemeral, was brilliant. The justices heard about the insult, but unable to see it for themselves, could not move against either Ames or his property. Customers drinking at the tavern must have toasted Ames’s victory in the contest of wits.

Perhaps his success with the sign also emboldened Ames to memorialize his struggle in a more traditional fashion. Ames Almanack for 1750 included verses “On a Judgment of Court obtain’d after a long Law-Suit.” Ames wrote,

Four times the Sun has in cold Pisces been,

The rising Pleiads have four Autumns seen,

Since I have stood th’ opposing Lawyer’s Tongue

Who puzzl’d Right, and Justify’d the Wrong.

Ames recognized that lawyers lived on words and their manipulation, but he also knew that images, particularly those located at sites of dense economic, social, and political exchange, could be just as powerful in shaping a critique of those “puzzl’d” and “Justify’d” words.

Further Reading: The best recent studies of eighteenth-century tavern culture are David W. Conroy, In Public Houses: Drink and the Revolution of Authority in Colonial Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, 1995) and Peter Thompson, Rum Punch and Revolution: Taverngoing and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1999). The best study of the material culture of taverns is Kym S. Rice, Early American Taverns: For the Entertainment of Friends and Strangers (New York, 1983). Earlier, more anecdotal studies, include Alice Morse Earle, Stage Coach and Tavern Days (New York, 1936) and Elsie L. Lathrop, Early American Inns and Taverns (New York, 1968). The Ames Family Papers at the Dedham Historical Society, Dedham, Massachusetts, contain the daybooks of Nathaniel Ames (1708-64) including “Medicines dispensed, 1737-50” and “Court Actions, 1740-53”; Ames Almanack, 1726-75; the diaries of Nathaniel Ames (1741-1822); and Family Papers (1758-1808). Court records for the cases involving Ames are found at the Massachusetts Archives, Boston, Massachusetts. They include: Superior Court of Judicature Record Books, Vols. 1740-45; 1745-47, and 1747-50; Suffolk County Court of General Sessions of the Peace, files, boxes 1707-49 and 1749-62; Suffolk County Court of General Sessions of the Peace Minute Books/Docket Books, 1743-54. Bibliographic information on law books published or available in the American colonies can be gleaned from Morris Cohen, Bibliography of Early American Law, 6 vols. (Buffalo, 1998). For discussions of property law and inheritance see Carole Shammas, “English Inheritance Law and its Transfer to the Colonies” American Journal of Legal History 31 (1987): 145-63 and Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill, 1986). For a discussion of Paul Dudley’s political and legal career see Steve Sheppard, “Paul Dudley: Heritage, Observation, and Conscience,”Massachusetts Legal History 6 (2000): 1-28. For a discussion of eighteenth-century court rituals and courtroom design see Martha J. McNamara, Courthouse Spaces: Architecture, Law, and Professionalism in Massachusetts, 1658-1860 (Baltimore, forthcoming). Lawyers’ use of language and performance in eighteenth-century courtrooms is explored in Robert Blair St. George, “Massacred Language: Courtroom Performance in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” Possible Pasts: Becoming Colonial in Early America (Ithaca, 2000): 327-56. Nathaniel Ames’s almanac prose has been edited and reprinted with annotation in Samuel Briggs, ed., The Essays, Humor, and Poems of Nathaniel Ames (Cleveland, 1891). For an analysis of Ames’s almanac writings see William Pencak, “Nathaniel Ames, Sr., and the Political Culture of Provincial New England,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 22 (Summer 1994): 141-158. The lengthy and fascinating diary of Ames’s son, Nathaniel Ames (1741-1822) has been published with helpful introductory matter and appendices in Robert Brand Hanson, ed. The Diary of Nathaniel Ames of Dedham, Massachusetts, 1758-1822, 2 vols. (Camden, Maine, 1998). Early histories of Dedham include Herman Mann, Historical Annals of the Town of Dedham (Dedham, 1847) and Erastus Worthington, The History of Dedham (Boston, 1827). A more recent history is Robert Brand Hanson, Dedham, 1635-1890 (Dedham, 1976).

This article originally appeared in issue 2.2 (January, 2002).

Martha J. McNamara is an associate professor of history at the University of Maine where she specializes in cultural history and the history of New England.