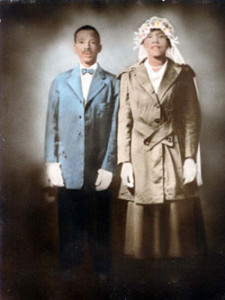

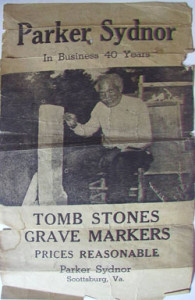

My curiosity about Vicey Skipwith began when her persona became intimately connected to research aimed at qualifying a newly identified pre-Civil War log cabin site for the honor of being listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register. The site was successfully listed on both registers in 2007. The historic log cabin site is named after my great-grandfather, Patrick Robert “Parker” Sydnor (1854-1950), a successful tombstone carver, who intermittently lived in the cabin during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (fig. 2). Vicey Skipwith and Patrick Robert Sydnor were contemporaries of the “First Generation”—formerly enslaved women and men who experienced freedom through the Emancipation Proclamation. As newly freedpeople regardless of their age, those African Americans were the first generation to experience citizenship ratified in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Ninety-six percent of formerly enslaved women and men were non-literate, and very few of the mere four percent who could read and write left behind autobiographical documents that revealed their inner lives and great ambitions. The search for the voice of Vicey Skipwith, whose life spanned the last nine years of slavery, the Civil War, Emancipation, Reconstruction, the beginnings of the Jim Crow South, and the 1930s Depression in New York City, was daunting because of her non-literacy. She left no personal papers or letters from her life. Yet, eleven years following the military end of Reconstruction, Vicey Skipwith was among the thousands of newly freed enslaved who amazingly established themselves and purchased land throughout Virginia. Regardless of the quantity of acres, each purchase was a truly remarkable achievement. In this way, the Patrick Robert Sydnor pre-Civil War log cabin site functions as a material artifact of slavery and as an unconventional text for autobiographical truths beyond slavery.

While I have not met anyone who has a living memory of Vicey Skipwith, I met several octogenarians who remembered Patrick Robert “Parker” Sydnor. In the mid-twentieth century, they knew someone who had been an enslaved American and thus, they touched living history. They were children at that time, and out of intergenerational respect, they called him “Uncle Parker.” Although he was a child at the time of Emancipation, Parker Sydnor was still a member of that First Generation. The cabin is historically associated with Parker Sydnor, who was one of its many inhabitants spanning the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

My project has engaged different kinds of challenges, interpretations, and research decisions because many of Vicey Skipwith’s contemporaries were technicians of the spoken word and they passed that skill to the next generation, and the next … They emphasized the texts of speech—collective memories and memory-telling. One of many challenges involved finding written evidence in support of what they told me—about people in the historic past, the landscape or material objects. For example, I’d been told by African American elders in the community that Aunt Lucinda had owned the cabin property. She had not. Her name was not on any of the deeds that I title searched. At some point during countless real and mental journeys to Virginia, I had an “aha” moment that cleared up the confusion of ownership and gift. True to the fluidity of memory-telling, Aunt Lucinda had owned the cabin because it had been given to her, purportedly by one of the white Skipwiths of Prestwould after emancipation, but she didn’t own the land. Undoubtedly, the log cabin could have been a gift. The valuable real estate, however, was not included with the less valuable personal property. Local oral historians had appropriately merged ownership of the log cabin with ownership of the land.

I’m reminded of the skillfully crafted book, The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth Century (2006) by historian Martha Hodes. Eunice Richardson Stone Connolly (1831-1877) was an impoverished white woman from New England, who in 1869 daringly married a wealthy sea captain, a man of color from the Cayman Islands. Alongside the intriguing narrative of the “sea captain’s wife,” Hodes has written a captivating account of her own journey of discovery into the ordinary and then extraordinary life of Connolly, as she went from rags to riches through an interracial marriage. Because Connolly was literate, Hodes could effectively conjure her up from the past, engage us with discovery and craft images of a nineteenth-century love story, constructed from the autobiography of letters and biographical actions provided by public records.

In her search, Hodes became a history detective and was able to resurrect a gendered autobiographical voice through the cache of Connolly’s letters. The raw skills of literacy are paramount in these kinds of exciting new discoveries and forensic investigations. Literate subjects leave private and public paper trails for contemporary historians to enjoy through discovery, interpretation, and placement. On the other hand, those of us who research enslaved nineteenth-century women and men seldom have the convenience of discovery that comes with the paper trails of literate people. Hodes was fortunate to research the sea captain’s lady who could read and write—who unintentionally left a wonderful and intriguing cache of letters for our historical fascination.

My Skipwith lady was non-literate throughout her life. She left no such cache. No epistolary paper trails. The central challenge for me was how to create a text for Vicey Skipwith. Given the facts, fiction, and truths, what kind of autobiographical voice could I craft for the larger text that would establish the narrative provenance of a surviving pre-Civil War log cabin? I needed more than routine biographical actions provided by public records. Out of this need, an organic process began to take shape. I sought out local people who were the cultural descendants of Vicey Skipwith’s world. Mecklenburg people liked the fact that there was national merit to their local history. So they talked to me and I listened. I didn’t conduct any formal interviews.

As historical narratives unfold, collective memories often carry the role of filling in the gaps and traces left by written history. During the early stages of the research, there was a potent interaction between written evidence (the facts) and oral witnessing (the collective truths). Fact and Truth: neither is mutually exclusive of the other. More importantly, I wanted to meet the research challenge by enabling material artifacts, such as a standing nineteenth-century log cabin, to act as a conveyer of truths. I could get the facts from written evidence, but how would I access personal truths from among people who didn’t write about themselves?

I place Vicey Skipwith’s story alongside my own journey of discovery—behind-the-scenes research encounters, humorous moments, challenges and expectations that helped me to produce a narrative of this elusive once-enslaved woman. Documentation is one of the prerequisites for a narrative of biographical facts. On the other hand, autobiographical perspectives are based on perceived truths of the subject. Autobiographical truths demonstrate that Vicey Skipwith’s decision to buy farm land in the aftermath of slavery and Reconstruction, gender restraints and the onset of legal segregation, shed light on her ambitions, character and diligence. These characteristics endow on a historic site the kind of meaning that the National Register seeks to honor with its signature recognition. I became a different kind of history detective.

How did I become involved in a project linking vernacular architecture, slavery, the Civil War and the search for Vicey Skipwith? My unexpected journey of discovery began when I had to return on family business to the South of my childhood summers.

After negotiating the hectic airport traffic streaming out of Raleigh-Durham, I settled into the driver’s seat and enjoyed the late morning—sunny, balmy, and quiet except for the hushed sound of the rental car’s engine as I sped north along Highway Fifteen from North Carolina to southern Virginia’s rural Mecklenburg County. Welcome to Virginia. Radar Detectors Illegal. Virginia is for Lovers. I crossed the state line, but I felt that I was crossing over to something more than signs could tell. At intervals there were the battered pick-up trucks and older model American cars going south on the other side of the two-lane highway. I slowed down when an occasional farmer or farm-hand driving his tractor turned onto the highway from a gravel road and travelled a short distance only to turn into the next gravel road. With only that kind of local traffic, I drove for almost two hours, alone on the north side of the highway. Townships and their white painted double-wides trimmed with foundation plants interrupted the forest on both sides of the highway; and intermittent field crops that I couldn’t name signaled small and middle-sized farms as the countryside became more agricultural.

Going back to Mecklenburg County after being away for more than twenty years, I was both uneasy and sad. My grandmother was no longer here to welcome and shelter me from the past. During the intermittent, but wonderful, summer vacations of my childhood and youth, I’d always been with family members in the old southern town of Clarksville: my grandmother, aunts, uncles, cousins and siblings. I had never been alone. The older relatives took care of everything. They spoiled us well. After all, being there was supposed to be like summer camp. We only had to play hard, eat well, remember our manners, take our baths on Saturday nights and go to church every Sunday until it was time to leave again at the end of the summer.

My empowering, well-known, feisty, tall and beautiful grandmother confidently did the driving, farming, cooking, shopping, helping the less fortunate, taking care of family property matters and sheltering us from the realities of Jim Crow in the South. As “summer” children, we only knew about southern white people and segregation from a far and emotionally safe distance. Now, my grandmother and the rest of the elders had all passed on. Because of my flexible summer schedule from university teaching in the Midwest, the siblings designated me to come back to Clarksville. Somebody in the family had to deal with the old uninhabited log cabin at the home place. I was anxious because the historical distances were shorter—not even past—and I had not come back to play.

I’d never been in Clarksville by myself, without my immediate family to cushion me from the historical remnants of a rural southern town steeped in antebellum history. One hundred miles south of Richmond and sixty-five miles north of Raleigh-Durham, Clarksville in 1818 became the first incorporated town in Mecklenburg County. It was named after Clarke Royster, a planter and tavern keeper, who also owned—among his extensive estates that included an elegant house, cattle, sheep and hogs—eleven slaves. Clarksville became a home front of Confederate operations during the Civil War. The closest major city in the next county of Pittsylvania is Danville, which is known as the last capital of the Confederate States of America. If you drive through Clarksville and continue north on Highway Fifteen, you arrive at the famous or infamous town of Farmville in Prince Edward County. As a result of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Board of Supervisors for Prince Edward County closed the public schools in defiance rather than integrate. In 2003 Prince Edward County apologized to the African Americans who as students had lost five years—an academic generation—of their education. But on that day of my return, I didn’t remember those epic junctures in Southside Virginia history.

Memories of those summers with my grandmother continued to swirl within and surround me as Highway Fifteen finally brought me to Clarksville (fig. 3). For a few days, I drove about the county conducting family business. I renewed my acquaintance with an elderly cousin who would come with me, and I appreciated her company. Not only did I have a “foreign” sounding name (because of my mother’s marriage to my Honduran, Spanish-speaking father) that many local people couldn’t pronounce, a name that was certainly not “from these parts,” I also “talked different.” I had to gain the confidence of the new people that I met. But during the early trips back for research I would watch their eyes glaze over until they could understand what I was saying.

Not long after my arrival, I went back to the log cabin site with a local history enthusiast—an elderly Mecklenburg County Anglo American with a keen enthusiasm for Virginia history. I’d been introduced to David Arnold in Boydton—the same county seat that Vicey Skipwith had gone to in 1888—and he wanted to see the cabin. We met at the intersection of the old Cabin Point—a name that had been given to the crossroads as long ago as 1798. I stood on the side of the paved county road and David walked through the underbrush up to the cabin (fig. 4). I didn’t want to venture that far because of possible snakes and unambiguous chiggers. After about fifteen minutes, he came back to the road, flushed with excitement. “That there log cabin has a lot of stories to tell, I imagine some from before the Civil War … you can get it on that Register …” I blinked. Was he referring to the National Register of Historic Places?

The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) sponsors the National Register of Historic Places. The NPS requires that a targeted site be researched with documentation that serves as proof of its historical value and national recognition. According to the NPS, the historic integrity of a building or site is “the authenticity of a property’s historic identity … Not only must a property resemble its historic appearance, but it must also retain physical materials, design features, and aspects of construction dating from the period when it attained significance.” While I researched and documented the integrity of the dwelling as a standing pre-Civil War structure, I also wanted to draw attention to how the site displays the cabin’s resonance and association with individual women and men—white and black—of the historic era surrounding the Civil War. The NPS defines association as “the direct link between an important historic event or person and a historic property … Like feeling, association requires the presence of physical features that convey a property’s historic character.”

In the process of establishing the historic integrity and provenance of the nineteenth-century log structure, I also pursued putting together the puzzle pieces of one of the cabin’s early inhabitants and first African American owner, Vicey Skipwith. David’s suggestion initiated six years of journeys that would take me back and forth through the historic past, to Virginia, to the Library of Congress, to many other private and public libraries and historical societies, and to the porches and churches of both African American and white American residents in Mecklenburg County. The log cabin property had once been part of the vast southern Virginia plantation, Prestwould, built by Sir Peyton Skipwith (1740-1805) with his second wife, Lady Jean Skipwith (1748-1826) (fig. 5).

Sir Skipwith made Prestwould into one of the antebellum “big houses,” in the tradition of Berkeley, Mount Vernon, Monticello, and Montpelier. Those elegant Georgian and neo-classical plantation houses embody the history of the elite planter families who created the foundations of the early republic. Similarly, Prestwould epitomized the wealth, character and emblematic ideals of that era in Southside Virginia. Prestwould was built by enslaved carpenters and stonemasons who brought stone for its construction from the plantation’s own quarry. An architectural historian from the Virginia Department of Historical Resources confirmed that the same quarry supplied stone for the chimney of the Sydnor log cabin (fig. 6).

I was fascinated by the fact that Vicey Skipwith was spirited enough to buy a parcel of the same land that her parents had labored on as enslaved workers. From tax records, I established that Vicey Skipwith was the tax payer for her six acres. But I had to do a title search to document the provenance of the property and its connection to Prestwould plantation. David volunteered to come with me and he invited the president of Prestwould Foundation, Dr. Julian Hudson, to meet us at the courthouse. Because my research encompassed historic Prestwould and its original ownership of the Sydnor log cabin, he wanted me to meet Julian.

David and I had no idea how to conduct a title search. Heavy leather-bound deed books were stacked imposingly on the shelves of the public records room at the Boydton Courthouse. Many of the books had beautiful handwritten entries that seemed to date from the formation of the county in 1765; but the cursive penmanship of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was difficult to read. I was sitting on the floor reading one of the heavy ledgers from the bottom shelf, when I noticed a pair of khaki-trousered legs standing beside me. Julian Hudson. I hadn’t heard him come in. And so, he had sized me up first. I stood up and introduced myself as David came over. We had been getting nowhere with the title search. Julian looked around the modest room filled with shelves of public records, old bound ledgers, maps and directories. He saw someone that he knew—a lawyer who specializes in estate and probate law. I found out later that Walter Beales is a highly respected Southside “lawyer’s lawyer” who also has an amazing knowledge of Virginia history.

Confidently, Julian walked over to the lawyer, greeted him and posed a statement rather than a question: “Walter, can you help us out here. We’re looking for … ” The lawyer looked at Julian, at me, and at David. I tried to look as helpless as possible. Walter Beales quietly and patiently stopped the work that he was doing for a client and showed us the correct sequence of bound volumes to search. With David and Julian taking command, in less than forty-five minutes we were able to complete the title search that covered more than 200 years of the property’s Euro-American ownership. The title search proved definitively that the Sydnor cabin property had been a part of Prestwould plantation, located in the area that had been the outlying slave quarters, called Cabin Point. The search additionally confirmed the dollar amount that Vicey Skipwith paid for her six and one fifth acres of land: sixty-two dollars. She also paid fifty cents in taxes the following year. Sixty-two dollars in 1888 is the approximate equivalent of $1500 in today’s economy—still a substantial amount of money. I could begin to connect the property “with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history,” as required for the National Register nomination.

After the triumph of that day’s research in the Boydton Courthouse, I thought about how social transformation in our American society enabled me to have ready access to public records that Vicey Skipwith would not have been permitted to access (even if she had been literate). With David, I entered the courthouse through the front door. His associates were white southern men who generously helped me with the title search. When Vicey Skipwith bought her property, she entered the courthouse through the segregated entrance. Nevertheless, she left the courthouse as a property-owning woman-citizen (fig. 7).

When I was not in Virginia doing field work, I immersed myself in reading about women and slavery, Virginia history, vernacular architecture, navigable waterways, material culture, and the Civil War. And every time I went back, I introduced myself to new people, especially the elderly. They were also “libraries.” As an African proverb tells us, when the elders die, libraries are gone. And so, I often went to the elders—black and white—in order to hear them talk through memory-telling. Because the church continues to be an important African American social institution, I attended different churches on the Sundays of my field trips in order to connect to the elders and their informational stories. I needed to know about the generations of people who had their home places where Vicey Skipwith had lived. I talked with local people, trying to get access to the cultural past through the voices of the present.

The elders who spoke with me seemed to prefer to use the less brutal sounding word, bondage. I observed that among them, slavery is still a word that causes emotional memories to collide. Bondage is associated with Biblical stories of injustice, impermanence and ultimate deliverance. “Slavery” as a distinct historical signifier evokes less of the deliverance and more of the atrocities. When the elders started remembering stories about the historic past and slavery, they would often begin with the signifying “we” of collective memory-telling, “When we were in bondage … ” Therefore, calling slavery by another name seems to serve as a shock absorber—bondage is a word that absorbs the distress of knowing about the abject poverty of the enslaved, about the violence and oppression inflicted, and knowing that the system did not make their people ignoble.

Many Mecklenburg County families—African American and Anglo American—are rooted in the antebellum and early republic history of Virginia. For example, J.J. Crowder was the former slaveholder who sold Vicey Skipwith the cabin property. He had bought it from Fulwar Skipwith (1836-1900), the last antebellum owner of Prestwould. Present-day families with the surname of Crowder still live in the county and are direct descendants of that nineteenth-century J.J. Crowder and his wife, Margaret R. Crowder. I was encouraged to telephone one of the Crowders still living in Clarksville. In his late nineties at the time, the contemporary J.J. Crowder was one of the town’s two oldest residents. He was good-natured as I told him about my project. He told me that his forefathers had bought Virginia land in the eighteenth century through charters issued by the king of England as land grants to private investors.

Referring to the log cabin property that had been sold to Vicey Skipwith by one of his ancestors and hoping to prompt any relevant information, I asked him if he knew about the older Crowder properties on the other side of the river, near a church named St. Matthew. He asked, “Do you mean near that white church over there on [highway] 49?” I thought, I’d made it clear that I was referring to African Americans in my research and no, I am not talking about any white church. Somewhat piqued, I replied with authority, “No sir, I’m talking about the black church at 49, after you turn off from the old Lee West store.” There was a slight pause through the telephone, and then he said to me with a bit of annoyance in his voice: “Well, I’m talking about the color of that church building. It’s painted white!”

As I kept going back to Mecklenburg County, I realized that I was not really alone. My grandmother was with me in a new way. She was still prominent in a community where people remembered her through memory-telling. Mentioning her name opened doors for me. The local people were not familiar with my surname because it was not among the names that had created rugged settlements, middling farms, plantations during the formation of Virginia as a Crown Colony of England, or home front operations during the Civil War. African Americans and Anglo Americans alike share those surnames such as Arnold, Burwell, Carter, Coleman, Crutchfield, Goode, Love, McCargo, Skipwith, Sizemore, Sydnor, Yancy.