“Who painted these paintings?”

Sorting my papers at the beginning of class I asked the student to repeat her question, as several of her classmates joined in. What I remember of the conversation follows.

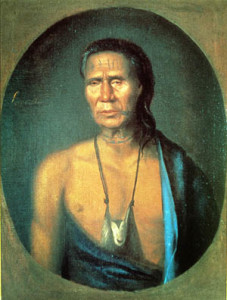

“These two chiefs,” she explained, “these Indians.”

“Pages thirty-one and forty,’ added a male voice.

Pushing aside my incomprehensible syllabus I lifted up Colin Calloway’s The World Turned Upside Down, a slim volume of Indian voices commenting on the white conquest of eastern America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. On pages thirty-one and forty were Lapowinsa and Tishcohan, chiefs of the Delaware, a tribe already betrayed and about to be betrayed again.

“Nice paintings,” I offered, and they were.

“No,” insisted the students, “none of the other paintings of Indians in this book is like these. Who did them? What made him see?”

I looked again. All the Indians in Calloway’s other illustrations looked at us as into a mirror, haughty, stiff, and hopeful. The limners who portrayed them had been equally stiff. Their flat colors, profiled poses and routine backgrounds were from a genre somewhere between tavern signs and a parody of the Great Masters. Lapowinska and Tishcohan looked out from wrinkled faces with the insightful eyes of men who had seen too much. The artist was not a master anatomist but he was a European painter who rendered his subjects in a space that once existed, a claustrophobic foreground deep enough for sculptural figures to emerge from the surrounding dark. A clear glaze over each painting intensified the faces, color, and detail. In these works the painter had risen above himself, above technique, above history. He had seen these chiefs for men.

“Who painted these?” my students asked again, “How could he see so well, why was he different?”

I read Calloway’s caption: “Gustavus Hesselius painted the two Delaware chiefs for the Penn family, Proprietors of Pennsylvania, before the treaty negotiations of 1735.”

Then I knew I would be able to seek an answer.

“Gustavus Hesselius” had to be Swedish. My wife’s family is Swedish, our son is Swedish, I speak the language and have done research there. In the last year and more, I have traveled far to find an answer to my students’ question. I’ve left Montana to follow Gustavus Hesselius from Stockholm to New York. Even now, after months of research, I cannot tell you for certain where Gustavus Hesselius got his clear sight during those days in the spring of 1735. But I can try.

I. Gustavus Hesselius is well known to art historians, and his name appears in encyclopedias. The typical entry reads,

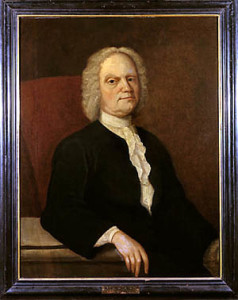

b. in Folkarne, Dalarna, Sweden in 1682, nephew-in-law of Bishop and statesman Jesper Svedberg. With his brother Andreas, a priest in the Swedish Lutheran Church, left Sweden in 1711 toward the end of the disastrous reign of Charles XII seeking opportunity in the former Swedish colonies in Delaware. Gustavus and Andreas arrived in Philadelphia in 1712. Their brother Samuel, also a priest, came several years later. Andreas and Samuel soon returned to take up parishes in Sweden but Gustavus, who had studied painting in Uppsala and Stockholm and was the first professionally trained portrait painter in the colonies, found clients for his skills in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and Maryland. He married and began a lineage of wealthy and artistic descendants in America. His son John (1728-1778) eventually moved south and painted the great planters of Virginia on the eve of the American Revolution. Gustavus Hesselius died in Philadelphia in 1755, at the age of age 73.

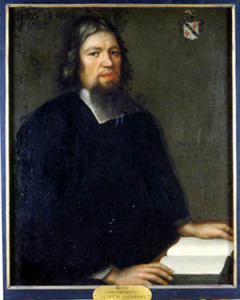

This entry alone opens worlds. “Toward the end of the disastrous reign of Charles XII?” By the year Gustavus Hesselius left Sweden, 1711, a fifth of its population had died of battle, disease, and famine in the course of King Charles’s endless war against Norway, Denmark, Poland, Saxony, and Russia. Constant counterattacks against this entire ring of enemies were the only way he could find to save a Swedish empire built up during the Thirty Years’ War. But he could never subdue them all simultaneously. In that same year, Charles endured a humiliating defeat deep in southern Russia and was interned by the Turks when he fled into their territory. Sweden would somehow hold out without him, but when he returned in 1714 to renew his obsessive campaigns his officers would assassinate him to end the nation’s suffering. By then Sweden lay open to conquest. Peter the Great dawdled with reforms while he moved slowly to pluck the Swedish fruit. Pieces of empire fell away like shuttle debris, Kurland, Estonia, parts of Pomerania. “Bishop and statesman Jesper Svedberg?” The patriarchically bearded Puritan whose piety did not prevent him from sweeping together the beginnings of a noble’s estate from the ruins of this crumbling Baltic empire? The man whose son, Emmanuel Swedenborg, would abandon it all to become a mystic? What stories!

And Hesselius’s paintings survive, too, dozens of them, in the Atwater-Kent Museum in Philadelphia, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and in the Maryland Historical Society. Art historians have spent decades identifying Hesselius’s paintings, dating them, digging out fleeting references to him in patrons’ letters, and speculating about the painter’s mentality from the ways he arranged pigment around the self-projections of the various members of the colonial elite whose commissions he accepted. Save for brief mention, his ancestors, contemporaries, and children and the historical mansions they inhabited might as well not have existed. One good reason for this focus on the canvases themselves was–and here I reveal Hesselius’s greatest secret–there are no papers. Neither the artist nor his limner son left more than a letter or two and a few legal transactions in the Maryland Archives. Remarks on or about the man in other historical documents are almost nonexistent. He is the ultimate circumstantial case, known only from his milieux, from stray inarticulate facts, and through the rare letter left by himself or others.

Finally in the 1980’s one historian of art, Roland Fleischer, assembled in a great exhibition and its catalog all that was then known of or could be seen by this Swedish painter. Fleischer viewed the paintings in the context of as rich a set of facts about Hesselius as had ever been collected. That was impressive, but the thing I noticed about Fleischer is that he felt a chill go up his spine when he saw the portraits of the Delaware chiefs. He had tried to express in scholarly language the excitement we all felt. “Of the Hesselius portraits, none is superior to these in expressiveness and sensitivity. Many portraits [by others] with more skillful handling are less sympathetically conceived and less capable of evoking the viewer’s interest. Even if Tishcohan and Lapowinska had unusually expressive faces, Hesselius was equal to the task. The nobility conveyed here on canvas is more basic and deeply rooted than that in the majority of eighteenth-century portraits. It rests on the solid foundation of human character and dignity. His powers of personal response to the subject before him were at their peak.”

I read this to my students. Yes, we thought, we felt it too. Though to us the expressions on those two faces were somewhere beyond nobility. Those men had seen almost too much. They knew that they would see more of the same, and that they would not lose their dignity.

Fleischer had also published what was then the only known letter by Gustavus Hesselius. What was interesting was not the letter itself but the fact that its appearance in print led Kathryn Carin Arnborg, an obscure graduate student in art history laboring in the ranks of doktorander at the University of Stockholm, to find another and far more significant letter by Hesselius. “I thought it was interesting that America’s first real portraitist was a Swede and that so little was known about him,” she told me when we met last summer in Humlagorden, the idyllic park in the heart of busy Stockholm. “So I rang up the Carolina (Carolina Rediviva, the great library of the University of Uppsala, sixty miles up the road from Stockholm) and they said, “Oh, yes, our files show that we have one quite long letter by Gustavus Heselius and several by his brother Andreas.” The item by Gustavus was a copy of his first letter home to his mother, written in June 1714, two years after he had disembarked in Pennsylvania, and it contained a revelation for those of us who thought that Hesselius had always seen Native Americans with sympathetic eyes:

Concerning the Indians it is a savage and terrifying folk. They are naked both menfolk and womenfolk, and have only a little loincloth on. They mark their faces and bodies with many kinds of colors . . . The womenfolk shave their head on one side, on the other side they let the hair grow, as long as other women. Here and there bald. They grease their bodies and head with bearfat and hang broken tobacco pipes in their ears, some hang rabbit tails and other devilments, and they think they are totally beautiful.

Some time they eat man meat when they kill each other. Last year I saw with my own eyes that an Indian killed his own wife in broad daylight in the street here in Philadelphia, and that bothered him nothing. While she was dying the other Indians sat around her; some blew in her mouth, some on her hands and feet. I asked one of them why . . . and he answered that a fire coal that would die you must blow on so that it will not go out. When she was dead they all began to shout and had so many awful effects that a man could be scared of them.

Twenty years before his luminous portraits of Lapowinska and Tishcohan, this frightened young immigrant had thought of painting Indian chiefs, but in a very different spirit:

I have always thought of painting an Indian and sending to Sweden . . . Last year one of their kings visited me and saw my portraits they astonished him very much. I painted also his face with red color he gave me an otterskin for my trouble and promised I could paint his Portrait to send to Sweden: but I did not see him later. The king is no better than the others, all go naked and live worse than swine.

When he first met them, Hesselius found Indians repulsive.

Two years after his landing the shock had still reverberated in his letter home. Nothing at home, not even in the collapsing Sweden of 1711, had prepared Hesselius for half-naked aboriginals murdering each other in the streets. Perhaps he still recalled the “filthy savages” he had seen raging in the streets of Philadelphia when, more than two decades later, in 1735, he portrayed Lapowinska and Tishcohan with warts and all. Possibly he meant by the meticulous details, the wrinkled skin, the worn, not spectacular traditional dress and ornaments, that there was still nothing noble about these savages? Their calm gaze and natural stance may have been all he could concede toward the still nobler images his patrons, the Penns, expected Hesselius to deploy to help them flatter the chiefs before they were robbed of their remaining tribal lands. But Hesselius could, on the other hand, have grown in wisdom in the twenty years since he wrote that fright-filled letter. He could have learned to admire the Delaware “savages” who fought so enduringly to preserve their homeland from European and Iroquois rapacity. He might even have become, like his brother Samuel, something of an early anthropologist, seeing in the Indians and their artifacts–in such objects as enigmatic war clubs with mute human faces carved on the killing ball–a lesson in human difference that evoked awe in him. And at the outer limits of human possibility, he might have learned to live with all the manifold “others,” the Indians, Germans, Scotch-Irish, and slaves, who already inhabited or, like himself, flooded into the middle colonies in the years 1712-35. Was it the wisdom of a wide tolerance that made his eye dispassionate? If Hesselius became one of the rare persons living in the American colonies in the eighteenth century who first learned to accept a multiracial society, that was a mystery worth exploring.

Early Pennsylvania would have tested any man’s tolerance. By the time Hesselius painted the Delaware leaders, Pennsylvania and adjoining sections of New Jersey and Maryland had already become the model of a new kind of society never before seen in the western world. Indians who refused to be conquered–for a while the Delaware and, south, the Catawba, and always in the north the Iroquois, once the dreadful power brokers of the continent and now the fast allies of the English in the mutual business of conquest and empire–demanded a place at every table. German immigrants in increasing numbers completed the temporary servitude that often paid for their passages to Pennsylvania. They made farms, became British citizens, and the Lutherans among them entered politics en bloc. Among themselves however the Germans fought constantly over religion, and fiercest were the battles of the Lutheran clergy against the Moravians, a sect of aggressive, successful, often female proselytizers rumored to observe weird sexual customs. In their lexicon, Christ’s wound became a vagina. It was as if the Savior had become female.

On the heels of the Germans came the Scotch-Irish, a wild tribal folk nominally Presbyterian who had been moved to Ireland to help subdue the still wilder Irish but had no use for any government and now moved west and south through Pennsylvania in their tens of thousands, taking land as they pleased, killing Indians to get more. Their practices dated from the era when the Scotch ballads had been conceived. Courtship by stealth preceded marriage by abduction. Hillbillies. My people. One Virginia aristocrat called them the “Goths and Vandals” of the age. Among the free English in the east, the prospering Quakers found themselves challenged for leadership by equally wealthy Anglicans and a few enlightened–as they saw it–Scotch Presbyterians. These religions in turn would be challenged, after 1740, by evangelical “New Lights” recruited from all ethnic groups, passionate laymen who regarded all the old churches and their educated ministers with burning contempt. On the coast a few remnant Swedes and Finns joined the mix, mingling with rowdy lascivious sailors and plausible Irishmen running from the Royal Navy or worse.

An underworld of sweat, despair, and deception played itself out on the roads. In eastern Pennsylvania the rising stream of English, Irish, and German indentured servants working for terms from three to seven years to pay for their passages to America was joined by increasing numbers of African slaves, until 30 percent of the labor force in Philadelphia and its hinterland was made up of one form or another of captives. White or black, all could be bought and sold. Many tried to escape. Thousands of advertisements in the Philadelphia newspapers invited bounty hunters to seize the runaways trying to flee from bondage. Scores of men who were little better off than their victims stalked these runaways. They made their livings by shutting up anyone suspect seen on the road and holding them without warrant in hope of a reward. When caught, the laborers ran away again.

Above the mounting cacophony stretched no established state church–for there was religious freedom here in Pennsylvania–and a proprietary government which, save for a rowdy elected assembly, was run by the Penn family. By this time the Penns had converted to Anglicanism and had become obsessed with turning their ownership of the land into massive profits. They found their efforts violently opposed by nearly every other group in the society when these groups were not distracted by their struggles with each other. Sometimes the several religious and ethnic factions jerked about under the manipulations of Benjamin Franklin, the magician of an apparently mad political system, but at other times Franklin’s clever tongue availed him nothing and he became a chip in the storm. No one ruled in Pennsylvania, least of all the king.

If our frightened Gustavus Hesselius got accustomed not just to Indians but also to this kind of society, he was a most unusual Swede. The newly arrived Hesselius would have had to travel far to become a tolerant man. If we are going to make of him a Jason without Argonauts, journeying toward regions of consciousness never before experienced, we need to know the mental distance we are asking him to leap. To understand how great that distance was, we have to locate him first in the almost otherworldly context of the Sweden from which he came.

Old Sweden was a hermetic social universe. By this I do not mean the collapsing Sweden of Charles XII but the ordinary everyday Sweden Gustavus grew up in, a Sweden whose assumptions endured largely intact until the 1980s. It was an extreme model of the way many eighteenth-century Europeans thought about society. Within Sweden itself, there was one folk, one church, and one true realm. By the eighteenth century the Swedish national self was so completely unified that it stayed behind Charles XII as he led the empire and the nation to ruin by facing more enemies than it could handle in the only posture he knew, attack. Only when the nation was exhausted, one in five of its population dead, its external territories disappearing and Russian armies about to invade, did a few officers shoot the mad king and save the nation. The nation could not save itself. It did not know how to disagree with itself.

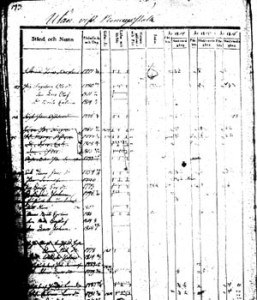

It is difficult to grasp the daily control exercised over this unitary society by its tribal state. Under something called the Indelningsverk–the Proportion Works–every village was assigned its share of the soldiers needed to defend the realm, and the empire. Local leaders met to provide a cottage–torp–for each soldier’s family while he was away in service, and when he failed to return they chose a replacement. They equipped their troops as sailors, artillerists, musketeers as specified by the Crown. There was never much debate about how many soldiers a given village should send, because the state church kept nearly perfect track of the population in every hamlet in the land. And in this role, as tracker of the population, the Swedish Lutheran Church was sovereign.

Gustavus Hesselius was raised in the parish of Folkaerna in Dalarna, in the traditional heart of Sweden.

Several times a year, usually in early spring and fall, when good weather made traveling easy, the minister came riding to each hamlet in his parish in a predetermined sequence. Nervous hospitality awaited him at the house of the biggest farmer in the settlement. Dressed in starched collars and black hats the host and his wife waited before the door. Every soul in the hamlet was gathered inside, standing in rough order of rank and age, old farmers and their spouses, younger farm pairs with their children, modest cottagers, day laborers, and male and female servants working on annual contracts for subsistence wages and small respect. Servant girls brought in warm drink or perhaps small beer together with aromatic bakelser from the kitchen hearth just behind the great room where the company stood gathered. Soon the minister, still called a priest–prest–lifted up the heavy house-examination book onto the dark farm table, opened it, and called the first name. It always fell to the host farmer to be examined first. The minister looked up from his book, pen in hand.

The pages of the book were ruled into small rectangles containing on the left a column of the names of the parishioners within this settlement by rank and family, their birth dates and ages. To the rightwards across the top of the page unrolled a series of headings. From each name in the left-hand column extended rightward a corresponding row of blank spaces such that every person would receive a score from the minister under each of the progressively unrolling headings at the top of the page. The headings spoke in plain language: “reading,” led the first, then “understanding,” then headings for various parts of Luther’s catechism, and farthest right a place for “notes,” which usually meant behavior. Every soul in the house would be tested by the minister on his or her ability to read and understand the Word of God as offered by the church and interpreted by it in the catechism. Notes were added describing anything unusual in the examinee’s condition or attitude. While not explicitly political, the catechism made clear that loyalty to the king as the head of the church, and so to the monarchical state to which the church belonged, was a duty to God. If you wanted to move, or marry, or take communion, you had to meet the standards set by the state and enforced in public by its local minister. The leader of the local farmers stepped forward. The minister asked the first question.

As those assembled rose one by one to be examined, it became obvious that there was a terrible democracy in the process. By the end of the day the meanest servant girl, rising last, could visibly outperform the stumbling master of the greatest farm in the parish. Everyone heard and everyone knew. To remove some of the sting the pastor kept his scores in code, but the meaning of these thin lines with crossing lines and dots above had long since become an open secret in the congregation. The bell-ringer had told his wife. Now they could follow the pastoral hand as he put the dots of highest distinction above the servant girl’s score that he had never entered for the farmer their host. Social pressure proved an effective spur to learning. By 1711 nearly the whole Swedish population could read fairly well and understand the Word and the world in the way their state and its church wished.

In every house in Sweden hung an embroidered picture of the hierarchies of authority in the nation. At the top of the picture was God, beneath him the king, who in principle must obey God, and below the king came the descending channels of secular and religious authority down to the individual household. Within the household the husband ruled over his wife, children, and servants, but his wife had authority over children and servants as well. The hustavla was the Swedish world at a glance. Like all his countrymen, Gustavus Hesselius had this picture in his head when he emigrated.

II. He had never seen anything like Pennsylvania. He was nauseated by more than just the Indians. His first letter home opens with a conventional pastoral praising the beauty and abundance of nature in the new land, but when he depicts the people of Pennsylvania he makes no attempt to disguise his disgust. “The people here in this city are mostly sinful and ungodly, a mixture of many religions. The teachings of the Presbyterians, Anabaptists, Papists etc. are a hindrance for our pure religion among our Swedish, who could easily be seduced. Therefore the parsons must daily travel around to them and teach them. God help brother Andreas!”

It is not in character for a Swede to use an exclamation point. Faced with all the people of Pennsylvania, Gustavus employed several. And while he seems to be alarmed about religion alone here, he is really using code words to give us his reactions to Pennsylvania’s people and society as well.

Every European knew that the Anabaptists had taken over the city of Muenster early in the sixteenth century and transformed an orderly burgher town into a sty of mad prophecy and free love. Catholics and Lutherans had joined forces to take the city, slaughtering the leaders of the movement together with most of their followers and hundreds of innocent victims. “Anabaptism” became a code word not just for religious heresy–after all, the very Catholics and Lutherans who had united to kill the Anabaptists called each other heretics–but for the way unregulated religious sentiments always created deadly social anarchy. In Sweden a stable religion carefully regulated by the state was the fabric around which national identity was woven. To lack a state religion was to subsist without group identity on the borderlands of chaos.

But Hesselius’ fear of all of the religions in Pennsylvania save his own appears a little irrational even by the standards of the day. Only a few dozen Anabaptists lived in Pennsylvania at the time Hesselius arrived, so they were no immediate threat. The “Papists” and Presbyterians he adds to his epistolary list of horrors were not remotely as alarming to a European as the anarchists of Meunster. From a Lutheran perspective the additional presence of Catholics and Presbyterians was not good, but elsewhere in the world each of these churches was a stable state religion. Only a handful of Catholics had settled in Pennsylvania at the time, and they could lose their property whenever Britain decided they had become too active a force in the colony. There was no danger from the Papists. Why, then, did all of these religions alarm him?

What frightened Hesselius was they were all there, and others on the way, different religions behind which lay different social groups, some from disorderly areas of Europe. He was also troubled that amid such excessive diversity many persons lived outside any church. “The people here in this city are mostly sinful and ungodly, a mixture of many religions.” “I have married a Calvinist,” he told his mother in the same letter, as if he could not believe he had done such a thing. By then he’d been three years on his own. But he assures Mama that his wife is pious, virtuous and god-fearing even so, and that “she wishes soon to leave this Sodom for our old Sweden.” Shortly thereafter he implies that the Indians’ religion is deviltry, moving the location from Sodom to hell. He all but tells her the smell of the Indians made him sick.

Swedish nausea was not unusual. Consider the Reverend Nicholas Collin, who arrived from Uppsala in 1771 to take up a rural Swedish pastorate and soon clambered his way up to the ministry of Gloria Dei, a Lutheran parish in Philadelphia itself. While he stayed on until his death in 1831, his attachment to America was chiefly conditioned by his ability to mingle with the elite of Philadelphia society, most notably in the ranks of the American Philosophical Society. As time went on his parish came to be surrounded by newer and poorer districts of the city. Collin reacted with violent distaste when the real diversity and “disorder” of America gathered beneath his window at night to wake him so he could marry them. He kept a special notebook in which he scribbled remarks furiously annotating the marriage records of his church, lamenting simultaneously the teeming “America” that came knocking on his door in Philadelphia and the revolution that had made it worse:

Came Margaret Power, who was married to John Martin, on the 22nd of December last, for a new certificate, as he had taken the first from her, and had left her on the very evening of the marriage. She was a widow, 27 years old, and he 26; natives of Ireland.

A Negro came with a white woman, who called herself Eleanor King, widow of a sea captain. They were refused.

Sunday. At night came a party, and with strong entreaties called me out of bed. On my refusing to marry the couple they went off in a vicious manner, throwing a large stone against the entry door.

A French captain of a privateer came with a young lady, from Baltimore. Begged very hard but refused.

A Swedish mariner came to engage my service in his intended nuptials: refused until he produced testimony of the woman’s character. Warned him not to forget his national character in this foreign alliance.

A Negro came with a white woman . . . I referred him to the Negro minister . . . having never yet joined black and white. Nevertheless these frequent mixtures will soon force matrimonial sanction. What a parti-colored race will soon make a great portion of the population of Philadelphia.

This wasn’t a population you could invite to a husfoerhoer.

The frequency with which national and racial differences are noted distastefully in these cases make it clear that Collin is not objecting simply to “disorder,”–though he definitely complains that bad laws from a weak state mean that there is no way to control a disobedient population–but that ethnic and racial diversity lies at the foundation of that disorder. He confirms this when he comments on his own marriage records: “From this will be seen,” he observed disdainfully, “what multifarious intermixing takes place continuously.” He continued the record obsessively, as if he were taming the disorder by condemning it in secret with his pen or leaving a record for God to avenge. In 1795, he wrote, “Oh, when shall I be cleared from this detestable place.” He had thirty-six more years to go. He never made it back to Sweden.

Nicholas Collin traces a trajectory Gustavus Hesselius had started upon but, I believe, never completed.

Hesselius, Collin, and their Swedish compatriots were not alone in their dismay at Pennsylvania. Nor was such dismay a European monopoly. Immigrants from New England experienced a similar revulsion. One such immigrant who arrived a few years after Hesselius was Benjamin Franklin, who was acquainted with Nicholas Collin and inwardly shared his sentiments. In many respects New England was another Sweden.

Puritan Massachusetts and Connecticut were also unitary societies with tribal governments. By the early eighteenth century, the Puritans had lost some of their original control of the colonial government in Massachusetts but still maintained a “New England Way” known for its tribal sense of identity. Only saints had the right to vote in church affairs or in colony elections. The rest of the people were presumably saints-in-waiting. Every tenth man, usually a saint, was a “tithingman,” who supervised the morals of ten families including his own. Certain of these practices ebbed with time, but far into the eighteenth century reactionary Puritan tribesmen would dominate the lower house of the colonial government and control the established church.

In 1723 young Benjamin Franklin fled Boston, Massachusetts, to take refuge in Pennsylvania. The young man had displeased both Increase and Cotton Mather, the archdeacons of the Puritan world. He ran to Philadelphia in 1723 lest the Mathers put him in jail or make his life miserable. Franklin throve in his new home, but Franklin’s reactions to his new home were quite complex. At first, no one thought him a Puritan. He began as a simple tradesman and soon progressed to scientist, politician, and man of the world. The diverse society of Pennsylvania did not seem to bother him. Franklin became a needed mediator between the factions of a divided society quarreling within a disturbed government, and in this role it was useful to have a reputation for tolerance. But when things did not go his way he could call down vengeance on his enemies like an Old Testament prophet. His enemies were usually people who were different from himself. He hated the Scotch-Irish, whom he secretly despised as barbarians, and of all people the Germans, who had had the effrontery to vote against his candidates for the colony’s legislature. When the Germans failed to support him he used a published essay to lash back at them and at “dark skinned” immigration in general:

Why should the Palatine boors [the Germans] be suffered to swarm into our settlements, and by herding together establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens, who will soon be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our anglifying them, and will never adopt our language or customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion.

Which leads me to one remark: That the number of purely white people in the world is proportionably very small. All Africa is black or tawny. Asia chiefly tawney. And in Europe the Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians and Swedes are generally of what we call a swarthy complexion; as are the Germans also, the Saxons only being excepted, who with the English make up the principal body of white people on the face of the earth. I could wish their numbers increased. While we are scouring our planet by clearing America of woods, and so making our side of the planet reflect a brighter light to the inhabitants of Mars or Venus, why should we in the sight of superior beings darken its people? Why increase the sons of Africa by planting them in America, where we have an opportunity, by excluding all blacks and tawneys, of increasing the lovely white and red?

Benjamin Franklin could leave Puritanism behind, but Puritanism–in the form of a desire for one people, pure and moral, under a single leadership–his–never left him. Nicholas Collin would have been insulted to be called “swarthy” but otherwise he and Franklin would have seen eye to eye. Nothing in their early lives had prepared them for Pennsylvania.

There were other reactions to the horrors of diversity. Consider Joseph Martin, an orphan boy raised in righteousness on his grandfather’s farm deep in rural Connecticut. In 1776 he left his simple but impoverished life as a farm laborer to join the revolutionary army. Private Martin marched with the army to camp in Valley Forge in the hard winter of 1777. His officers assigned him and other Connecticut lads to collect food for the army from local German farmers because the polite New Englanders were more effective foragers than the ominous “one-eyed men”–the eye-gouging Scotch-Irish–who had joined the Continental Army there in Pennsylvania and from points south. In the spring, when the British army evacuated nearby Philadelphia, troops from Pennsylvania joined Washington’s army to help pursue the British back across New Jersey and into New York. Martin came along but hung back, assigned to forage on the rich farmers of Jersey. While he was resting by the side of the road the American army’s “baggage train,” as it was called, creaking along miles behind Washington’s regiments, caught up to him. Last in the line of wagons came Pennsylvania’s “baggage,” a rowdy collection of teamsters, camp followers, wounded, and shirkers from every folk group in that colony. The one-eyed men were there; so was everyone else. Franklin would have named it Hell on Wheels. Martin was transfixed:

Our baggage happening to be quite in the rear, while we were waiting we had an opportunity to see the baggage of the army pass. When that of the middle states [Pennsylvania, New Jersey] passed us, it was truly amusing to see the number and habiliments of those attending it; of all specimens of human beings, this group capped the whole. A caravan of wild beasts could bear no comparison with it. There was “Tag, Rag, and Bobtail”; some with two eyes, some with one, and some I believe with none at all. They beggared all description; their dialect too was as confused as their bodily appearance was odd and disgusting. There was the Irish and Scotch brogue, murdered English, flat insipid Dutch [German], and some lingoes which would puzzle a philosopher to tell whether they belonged to this world or to some undiscovered country.

More fascinated than repelled, Private Martin had discovered America.

I’m not sure Gustavus Hesselius ever made it this far.

III. Yet the paintings did not lie. There is evidence beyond the enigma of oil on canvas to tell us that Gustavus Hesselius began to cross a threshold many Americans then and since have been unable to cross. What happened to him in Pennsylvania changed him progressively but the transformation was latent in his past, a past that distinguished him from his brothers Andreas and Samuel, who did not stand the course but left American to return to Sweden.

The secret lies in a closer reading of Gustavus Hesselius’s first letter home, and in what is known about his life experiences in Pennsylvania and nearby in Maryland and New Jersey over the next forty years.

He began to change already before writing the letter. I believe he knew this and that he wrote the letter in part because he knew he was changing and needed to assure his mother and perhaps himself that she would not lose him entirely. In the simplest sense, of course, he had waited two years to write her because he needed to know that clients would seek out his services and he could earn a living. Unlike his brothers, he was a freelance artist with no churchly sinecure to guarantee him income. Only in 1714 was he certain he could stay a while, though probably he did not know how long. Brother Andreas had surely used his first official report back to the Swedish Church to ask Uncle Svedberg to tell their mother, the bishop’s relative, that both he and Gustavus had arrived safely across the sea. Gustavus could not have written her a detailed message before being certain he could stay at all. But by the time he wrote her he had already broken convention powerfully. The first thing he had done once income appeared certain was not to write his mother but to marry, and in marrying he had passed over the many attractive young women of the Swedish congregations who for generations provided good wives to imported Swedish clergy–including one of his brothers and later Nicholas Collin–to take the hand of a Calvinist.

In choosing to marry Lydia Getchie he sent a double message, one of several signs in the letter that he had a more complex reaction to his new environment than his words of revulsion might indicate. On the one hand the lady was a Calvinist from a unitary society expressed in a tribal state, Connecticut, so she shared certain assumptions with her husband and probably shared his dismay at what appeared to be Pennsylvania’s chaos. On the other hand she was a Calvinist, a religion regarded by Lutherans and Anglicans alike as fanatical and disreputable. The only real Calvinist states included the Netherlands, an internally divided and declining power, a few Swiss cantons, contentious Massachusetts, tiny Connecticut, and a Scotland notoriously rent with bloody struggles between shifting combinations of highland Catholics, lowland Calvinists, and the imperial English. By comparison, Lutheran Sweden and Anglican England stood in the top rank of powerful European states. They prided themselves on being stable sovereign powers possessed of substantial empires. Precisely because its empire had begun to fray at the edges, no nation had more confidence in the rightness of its religion than Sweden. To marry a Calvinist was déclassé and a flirtation with heresy if not anarchy. Hesselius had done something bold. For whatever reason, loneliness, lust, ambition for her dowry, a sophisticated wisdom that leaned him toward the new fashion for tolerance, or all of these at once, he had stepped outside his own intolerant framework. This meant that he had some heavy explaining to do to mother.

Because Hesselius knew his mother would be horrified, he broke the news to her in crafted form in his letter. He conceded that she would be shocked, but he did it in a way that clearly put a touch of humor on the news, admitting that Lydia’s father is a “Presbyterian or Calvinist a mean odd fellow,” a cartoon Calvinist. But, he observes lightly, the man might yet be saved because his other daughter has married an Anglican parson, “so we can hope for the best.” There is a nice mix of conventional shock and worldly insouciance in this passage that his mother may read as she likes. Besides, the old man has placed his substantial estate at the couple’s disposal “while I stay here in this country.” He then amplifies this implied promise to return home when he affirms that his bride has converted to Lutheranism and is really an honorary Swede by virtue of her virtuous demeanor and her intentions to move promptly back to Sweden with him. It is at this point that he refers to Pennsylvania as “Sodom,” something he half believed at this stage but that was also useful in diverting Mama’s attention to greater evils than a once-Calvinist bride.

Hesselius’s letter shows in many ways a more complicated man than my students or I imagined. He is, for example, overwhelmingly ambitious. His father-in-law’s stone house and fine gardens are lovingly portrayed. “Since I came to this country I have earned 600 pound,” he notes (a good living for a minor nobleman in England ) and “I lived a year with Master Easton one of the most noble English.” The passages that report his revulsion with the natives also strain with his desire to paint them. Art and ambition combine to make him say, even as he reports behavior vile to his sensibility, “I have always thought of painting an Indian and sending to Sweden.” But art alone speaks when one of their kings is astonished by viewing the painter’s oil portraits and, to return the compliment, Hesselius takes his own red pigment to mark the king’s face in Indian fashion. For an instant the artist touched the face of the other, painting the face of strangeness in a strange manner, and asking in wonder what this other way of painting meant. But when the king does not return to sit for Hesselius he and his like become “swine.” Still, just as in the letter we can see that his religion was already bending to embrace one converted Calvinist and her Anglican brother-in-law, so here for a second we can witness Hesselius and an Indian chief gazing at one another, each wondering what magic lay in the art of the other. I do not think this Hesselius is a conventional man. His later life would confirm this impression.

As the years passed word of his professional skills spread through the colonial elite. Commissions for portraits mounted, and it became clear that Gustavus and Lydia would not move to Sweden. He produced scores of works, dozens of which survive. Collectively these paintings tell us that the searching eye of the trained painter could override Hesselius’s ambition as well as his prejudices. He became a portraitist of men, not of women. The absence of paintings of women in his oeuvre puzzled art historians until they turned up a rare piece of documentary evidence that explained the dearth of women. By chance one of his foremost patrons, James Logan, chief justice of Pennsylvania, wrote to a friend that Hesselius would do his likeness but that his wife had refused to be painted by the Swedish artist. In so many words Logan described her complaint as, “He paints what he sees.” Hesselius’s renditions of his sitters’ faces, noted the chief justice, struck most of Pennsylvania’s gentlewomen as too “unflattering.” Gustavus’s ruthless eye took him places he did not want to go. When he lifted his pigment to daub a tribesman’s cheek, when he studied the signs of age in a woman’s visage, his eye ruled him. Whatever he felt about Indians or however much he wanted a commission, his painter’s eye drew him along, whispering, “Accept. Accept. Paint what you see. Nothing human is foreign to me.” Ambition, a fashionable tolerance, and his eye motivated this man, and this time the eye won. Rather than compromise, he went on painting men.

By the time Hesselius accepted a commission to paint a large mural in St. Barnabas Anglican Church in nearby Maryland in 1720, it became clear that he could never remain in the Lutheran fold. Jesper Svedberg had ordered the Swedish Lutheran clergy in America to maintain friendly relations with the Church of England, and, on the way to Pennsylvania, brother Andreas had persuaded the bishop of London to contribute financial support to the Swedish mission there from the Anglican missionary funds for America. The bishop gave gladly, as his church was short of good priests who would go to America and the Swedes preference for moderate religion and strong civil government fit nicely with Anglican goals in the colonies. But Anglicans were not Swedish Lutherans. They served a wealthier clientele and cultivated a stylish stance as religious citizens of the world who were able to see good in many other faiths. When St. Barnabas offered Hesselius a substantial commission to do a mural of the Last Supper, it offered him several temptations. The growing fashion for tolerance among men of the world may have joined social ambition and a good fee to persuade him to take this commission, but, as will become apparent, I suspect that his eye was engaged by this new faith as well. Accepting the job would draw him closer to the visual world of Catholicism, yet another of the religions whose multifarious presences had so alarmed him (though not enough to keep him from his Calvinist bride) in 1714. In all events after he completed the work he spent as many of his Sundays in Anglican churches as in Lutheran, and joined at least one Anglican congregation as member in full communion. From then on he was as much Anglican as Lutheran.

Unlike the still fairly barebones Lutherans, many sophisticated Anglicans had begun to move back toward the Catholic pictorial tradition. Lutheran priests no longer whitewashed religious paintings out of frenzy for the unvarnished word of God, and churches in Sweden had begun to indulge in baroque decorations and occasionally in paintings (indeed, Hesselius had done an altarpiece for a local Lutheran church in 1715, the first religious painting in the colonies). But Lutheranism like most Protestantism remained essentially a religion of print and of the mind. The vivid images of the Protestant tradition still lay in the minds of their despairing believers. The Catholic pictorial tradition, however, was literal, and it stretched back unbroken for centuries. In that church no infusions of reforming asceticism had ever broken the passionate attachment of lay believers to vivid physical representations of Christ, Mary, and the saints. Catholic patronage had generated an abundance of great religious art by the masters of the Renaissance whose art Hesselius had studied in reproduction while training in Uppsala. Throughout the Catholic universe an abundance of statues and colorful plaster or canvas surfaces displayed the miracles and mysteries on which popular faith was grounded. Catholic reformers complained that the people thought that the images were the saints they depicted.

Anglicans had never fully rejected this tradition, and now in the middle of the eighteenth century high Anglican congregations like St. Barnabas returned more eagerly to an appreciation of the spiritual value of pictorial representations than some Lutherans were prepared to do. Anglican piety had never been entirely demysticized. The churchwardens commissioned Gustavus Hesselius to paint “ye History of our Blessed Savior and ye Twelve Apostles at ye Last Supper. Ye institution of ye Blessed Sacrament of his body and blood.” When Gustavus Hesselius promised to do a mural at their church, he entered a world of visual piety that his Anglican friends took seriously, and that he had never fully experienced. To some of his brothers in Luther, it must have seemed impure superstition. To him, it may have become pure pleasure. The painting is gone, but the clue to his reaction lies in something he did after. He became an Anglican but, years later, not long before his death, he painted out of his own need the most passionate of representations in all Christianity, the Crucifixion, which he exhibited in the window of his home in Philadelphia. It must have caused talk. If this is the Crucifixion that John Adams later saw in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic church in 1774, it was Catholic indeed: “A picture,” writes Adams, “of our savior in a frame of marble over the altar, at full length, upon the cross in agonies, and the blood dropping and streaming from his wounds.” Did Hesselius’s eye and heart finally lead him from a Calvinist bride to a Catholic piety made for a man with a pictorial imagination? There was no fashion in this, so he would have had to keep it secret.

In 1720 he also sold the land in Maryland that he had named “Swedenland” and the following year became a naturalized British citizen, in Maryland. He could never go home to Sweden, metaphorically or literally. Greater Philadelphia was his home. His children attended the English-language services at their Swedish church, not those in Swedish. Eventually he made his home in Philadelphia itself. He continued to do well. Part-Lutheran and part-Anglican, possible sentimental Catholic, once the groom of a Calvinist, he had become everything that in his letter home to his mother he had claimed to despise.

IV. Gustavus’s brother Samuel met an altogether different fate. Samuel arrived in Pennsylvania in May 1719. From the moment he arrived Samuel spent as much time preaching in Anglican churches as in Lutheran, eventually acquiring an Anglican congregation of his own. When he left Pennsylvania to return to Sweden in 1731 most of the letters of thanks for his efforts were from Anglicans, not Lutherans, and the English priests praised his broad piety and enlightened faith. He was not as popular with some of the Swedes he had been sent to minister to because he was willful and was accused of scandalous behavior, but also in part because he was the first Swedish Lutheran missionary to America to try to convert his Lutheran services entirely to the English language. He could not rest content as a man of the world himself, unless his fellow Swedes in America too joined the world. In this initiative he reversed the whole purpose of Sweden’s great mission to its people stranded along the Delaware littoral, which had been to preserve their national character in the midst of Pennsylvanian chaos. He was an assimilationist. He perceived that the English religion, culture, and language would become the matrix for whatever order would emerge in this tangled land. His effort failed, and he was roundly criticized by some of his countrymen.

Samuel may have been a catalyst in his brother’s ongoing changes. At the behest of their stay-at-home brother Johan, a doctor and the only Hesselius sibling who could be called a scientist, when he went home Samuel took with him a “chest of curious things” that were to weave their way into his country’s increasing awareness of the wide world. Samuel Hesselius’s chest of curiosities is mentioned in the letters of Killian Stobaeus, the founder of the first historical and ethnographic museum at the university in Lund. From there Staffan Brunius, a curator at the modern National Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm, has traced the objects through the papers of the aristocratic scientist Carl Gyllenborg, who in 1739 left the chancellor’s post at Lund to become chancellor at Uppsala and a founder of the National Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Evidently Samuel sent the chest to Gyllenborg in Lund in 1736 with a request that the objects go to his home university of Uppsala. Some of the objects in the chest may have stayed in Lund–whose museum now hangs on the edge of nonexistence as state support is withdrawn–and the rest evidently followed Gyllenborg to Stockholm where some items are probably in the collections of the Ethnographic Museum, though a few may have come to rest eventually at Uppsala. Samuel and brother Johan had catalogued the collection in the years immediately after Samuel’s return from America, but their catalog has disappeared. Samuel’s letter donating the chest mentions many Native American items including “a stone axe,” “an Indian idol,” and “a belt of wampum,” but because the early objects sent by him and others created a fascination with Indians, the ethnographic collections in Lund, Stockholm, and Uppsala are now so full of similar American Indian artifacts of unspecified origin that we cannot know which were sent by the returning missionary.

It is impossible to know which native objects in Lund, Stockholm, and possibly Uppsala were sent by Samuel Hesselius, but it is possible to know in what spirit he sent them to Gyllenborg. In Skolkloster, the seventeenth-century castle on the inland sea called Maelaren, cached among artistic booty seized by the victorious Swedes during the Thirty Years’ War, is a Delaware war club whose like exists in only two other places, Stockholm and Copenhagen. On its killing ball a mute face has been carved.

The face is round mouthed in unreadable emotion. In the seventeenth century such objects were called “curiosities.” They were collected by aristocrats for display in their castles for the sense of wonder they evoked, of distance, of strangeness. In 1736 Samuel sent his “curious things” to Carl Gyllenborg in quite another spirit. Gyllenborg represented a new, “scientific” approach born of the Enlightenment and out of which modern ethnography would emerge. While it was still an aristocratic plaything, the systematic study of strange cultures was about to begin. Just as brother Gustavus’s letter home survived in a copy in the collections of Germund Ludvig Cederheilm because that aristocrat wished to appear an aficionado of the natural sciences, so Samuel’s letter donating his chest of curiosities survives because it was saved by another aristocrat reaching for science, in this case anthropology. But in his terminology, “curiosa saker,” Samuel revealed that the old sense of pure wonder was not dead in him. Creature of human wonder as well as of the Enlightenment, he marveled at the enigmatic objects he forwarded even as in sending them he made himself a scientist and honorary gentleman.

Immediately on Samuel’s arrival in Pennsylvania in 1719, Gustavus began his journey toward Anglicanism and into an ancient and vivid pictorial piety that high Anglicans had never entirely rejected and liberal Anglicans no longer scorned. And soon thereafter, in 1721, he became a citizen of Britain’s world empire, embracing that as well. I cannot help but see Samuel’s wide, tolerant, assimilationist, and, yes, also personally ambitious stance as a spur to his brother’s own growth in these years. Both were becoming men of the world, at home in several traditions. I believe that Samuel’s sense of wonder infected Gustavus as well, and perhaps always had. In 1735, four years after Samuel returned to Sweden and one year before he sent his Indian objects off to Carl Gyllenborg, Gustavus received a commission from the Anglican Penns to paint two Delaware chiefs, Lapowinska and Tishcohan, before a conference that would end in their betrayal. By this time, Gustavus’s ambition and hunger for new experience were beginning to take him far from his origins. His eyes had seen much already. The gazes of his two subjects in the paintings come from the same source of wonder as the silent open mouths of the figures on the Delaware stone clubs in Skolkloster, in Stockholm, and in Copenhagen, or the lost objects from Samuel’s trunk. Samuel and his brother bore simultaneous witness to what was disappearing.

Out of the encounters of cultures, Swedish Lutheran, migrant Calvinist, enlightened Anglican, and Native American, out of social climbing, the uncontrollable passions of the eye, out of a fashionable and socially useful cosmopolitanism and assimilationism, and a not entirely modern sense of wonder, came Samuel, who went home with his chest of curiosities, and Gustavus, who remained to paint the two portraits that so moved my students.

And what happened to Lapowinska and Tishcohan? After their portraits were completed they attended the meeting to which the Penns had summoned them. There they were persuaded to agree in principle to a further purchase of their tribe’s lands in the future. Two years later, under immense pressure, they accepted the Penns’ offer to buy for a fixed sum as much land as a man could walk in a day and a half. On the nineteenth of September 1737, the Penns showed up with three trained runners, the strongest of whom in the next thirty-six hours “walked” off the boundaries of an area nearly a thousand square miles. The Delaware were dispossessed of their homeland. In succeeding years they became vassals to the Iroquois, who called them “women” to their faces at treaty negotiations. The Iroquois sold the tribe’s remaining lands to the Penns and to other land speculators, taking the small profit for themselves.

Coda

Hesselius’s story and the Delawares’ fate are more complicated than they have been rendered here. My portrait of the artist would be different now if I could incorporate the sources that have poured across my desk since writing and submitting it. To me he now seems a more deeply moved, even spiritual, man.

I say this first because of the terrible story of his brother Andreas, with whom he had crossed the Atlantic to Pennsylvania and met his first Indian. In my view news of Andreas’s final fate has to have influenced Gustavus just as he raised his brush to portray the two chiefs. Andreas was thirty years old and a rising star on the faculty at Uppsala when he attracted the envy of Bishop Svedberg. The bishop deliberately sent Andreas to exile in America for ten years, as far as he could send him from all opportunities to shine intellectually. Presumably he did it to punish him for pride but Andreas’s brothers, who loved him, did not see pride in him, nor do I. But I do know university politics in Sweden and to me the story is familiar. Peter, the next eldest and himself a priest, spoke for them all when he publicly lamented Andreas’s banishment to limbo, finding nothing good in it. Svedberg then came down hard on Andreas when some of his first reports home on the Swedes in America did not fit the rosy views of the official line. Pennsylvania was hell for Andreas as well, as both Svedberg and Andreas’s brothers had anticipated. When Gustavus had exclaimed, “God help brother Andreas!” it was because he knew that the spirited and widely learned Andreas would suffer trying to bring orthodoxy–let alone sophistication–to colonial Swedes and Finns used to making their own decisions and tempted by the wide choice of ignorant heresies plaguing the land. Once again, with new knowledge Gustavus’s letter acquires deeper dimensions.

Andreas assumed his duties, bearing it so well that even Svedberg grew silent. By the time Gustavus had written, Andreas had already married a local Swedish woman the very day Gustavus wed Lydia, and he twinned with Gustavus’s letter a message of his own informing their mother. When he was allowed to go home after serving his ten years, the parishioners of his Christina congregation gave him warm recommendations. He later admitted that only good books and his interest in botany had enabled him to bear his time in America. His notes at the time also show a remarkable human fascination with the Indians. Enlightenment language occasionally came from his pen, and a draft of a play that summed up the contradictory fantasies about Indians then fashionable in liberal circles, but he was simply a trusting father as he watched an Indian woman cure his sick little son, and spoke only as a reflective fellow thinker when he described the religion of the local tribes. He felt so keenly the destruction that conversion to Christianity worked in Indian converts by cutting them off from all their traditions and companions that he could not bear to fulfill his duty to convert them. Israel Acrelius, who was later sent out to report on the state of the missions to America, would ridicule Andreas for his failure to bring over ‘the heathen,’ but Andreas could not inflict cultural limbo on a people whose views he respected. Most of all, he looked Indians in the eyes. At an early conference attended by Iroquois chiefs, he noticed how the eyes of one chief and his wife revealed an openness and kindness that dispensed with the standard mask of native pride. Perhaps he shared these revelations with Gustavus, who came frequently to his brother’s church.

Andreas had a miserable life after he returned to Sweden in 1723. His wife died in England on the way home. Svedberg sent the widowed man to Gagnef, a parish located near his home in Dalarna but a congregation run by a clique of headstrong elders and a schoolmaster who tortured him for years. Gagnef was worse than Pennsylvania, and far, far from Uppsala. He died a lingering, painful death, probably of cancer in 1733, never having made it back to the center of things. News of Andreas final suffering and death must have reached Gustavus shortly before he painted Tishcohan and Lapowinska, looking into their eyes, seeing in them suffering, endurance, understanding.

The last story is the most dramatic of all. After Lydia died, in 1748 or ’49, when he was only a few years from death, Gustavus Hesselius is reported to have gone to a Moravian leader to help him with the guilt he felt over having beaten his female house slave. Before and after that reported visit, his known contacts with the Moravians increased steadily. The Moravians did not yet forbid slavery, but they were on missions throughout the world to convert slaves, Africans, Eskimos, and all peoples, to their celebratory beliefs. They had already eaten out Pennsylvania Lutheranism from within, pretending to supply qualified ministers while converting most Lutherans to their increasingly unorthodox positions. By 1745 it was becoming known that the Moravians believed the deity was female as well as male, worshipped images of Christ’s wound as a vagina-like opening in which they painted little believers living happily, and celebrated in poetry and on actual occasions the union of male and female sexual organs in marital intercourse. Lutherans and Calvinists throughout Pennsylvania reacted in horror, while the Anglicans looked on with a certain superior amusement.

Despite their reputation, by the mid-1740s Gustavus Hesselius had joined the Moravians, by then about the least fashionable thing he could do. He stood side-by-side with them as they fought the long and sometimes bloody battle for religious preeminence with Swedish and German Lutherans that lasted from 1744 to 1750. His conversion in these years puts the painting of the Crucifixion he hung in the window of his town house in Philadelphia in 1748 in a new light, for the painting now appears not as part of a drift toward Anglo-Catholicism but as a bold public declaration of his adherence to the Moravians and to their vivid revival of the medieval Catholic piety centered on the wounds and blood of Christ. In a letter to the Moravian leader, Count Von Zinzendorf, the Moravian Bishop Cammerhoff tells how seeing Hesselius’s Crucifixion in Philadelphia helped make two slaves aware of Christ’s suffering and open them to this Moravian piety.

Late in his life, then, Gustavus entered the portals of a radically unfashionable religion centered on turning holy suffering into holy joy and actively opening its arms to all peoples alike. I had always suspected that he was a spiritual adventurer, a man of suffering, and of conscience. His daughter and her Lutheran-priest husband barely pulled him back into the fold of respectability before he died. His paintings of Lapowinska and Tishcohan were only the first of his depictions of suffering.

As for the Delaware, already by Hesselius’s death some of them were becoming Moravians too. Their children would live as Moravians at a village named Gnadenhutten.

Sources and Further Reading:

After having completed this work I discovered that Gunloeg Fur had raised the very same set of questions about Andreas and Gustavus and the two paintings in her “Konsten att se,” in Historiska Etyder, published by the department of history at Uppsala University, 83-94 (Uppsala, 1997). Fur’s brilliant opening, and awareness that it is the conditions of clear, tolerant sight of others in a few Europeans that we must investigate, make hers the pioneering work in the field. Without full use of the archival sources in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania or the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, she romanticizes Andreas as a kind of woodland Swede, senses but then drops the importance of Gustavus’s ties to his brother and to the Moravians, and explains the tolerant vision of both by a “marginality” that may not describe either Gustavus or Andreas very exactly. Nonetheless, I have tread inadvertently in her early footsteps, and hope I have been able to refine her depictions of these events so that we can one day return to the issue of marginality with more knowledge.

As far as I know the only fiction in the essay has just been pointed out by one of the students from the class, who remembers that only one of the paintings was in Calloway’s book and that another member of the group had found and brought a copy of the other to that class. I checked the book and, sure enough, there was Lapowinska alone. Otherwise I have not relied on memory. While I here make interpretive choices on larger historical issues, the only unconfirmed evidence specifically on Hesselius and his brothers is a) that the crucifixion John Adams saw in a Catholic church in Philadelphia in 1776 is the one Hesselius placed in his window in 1748, and b) that in the 1740’s he went to a Moravian leader to discuss his guilt over beating his female slave. In both cases respectable older authorities either cited sources inadequately or named sources since lost. I have tried to write the text to reflect the uncertainty of these two claims. Otherwise I have looked up every fact in original sources or in reliable secondary works that footnote specific original sources and are often confirmed by others’ citations. I have not used footnotes not only because this journal in its wisdom prohibits them, or because this is a work in progress, but because there is neither certainty nor science to the origins of tolerance pursued through a myriad of oblique sources. It delights me to write an informed reflection on an issue that I hope can never be resolved and to name the sources only at the end so as to invite others to make the same journey. If we were to find Gustavus Hesselius’s personal papers and they were to reveal a single specific source of his tolerance, I would be disappointed.

We begin with Colin Calloway, The World Turned Upside Down (New York, 1994). For Gustavus himself and his painting, the older and still useful work is Christian Brinton, Gustavus Hesselius, 1682-1755 (Philadelphia, 1938) and the modern classic is Roland Fleischer, Gustavus Hesselius, Face Painter to the Middle Colonies (Trenton, 1987). Fleischer also has an article, “Gustavus Hesselius and the Penn Family Portraits,” American Art Journal 19 (3) (1987): 4-18, a piece which led Carin Arnborg to find and publish Hesselius’s long letter home used here, as “‘with God’s blessings on both land and sea’: Gustavus Hesselius Describes the New World to the Old . . .,” American Art Journal, 21 (3) (1989): 4-17. Arnborg’s essay in history of art at the University of Stockholm, “Gustavus Hesselius in Sweden and Europe from 1682 to 1712” (1989) is in English and very valuable. All of these works list most of the vital documentary sources. Carin Arnborg had the assistance of Swedish antiquarian Lars Oestlund in her work, and she has kindly provided me with copies of his excellent and almost perfectly footnoted private (Xerox, bound) work on Andreas Hesselius, “Andreas Hesselius, Dalapraest och naturskildrare I 1700-talets Delaware” (1993), a work deeply based in a fine reading of original published Swedish sources. It should be published. Oestlund’s earlier Hesselius, Den Bortgloemda Slaeken (Avesta, 1989) covers the family as a whole, has a specific and valuable essay on Gustavus, and is based in many original sources, but is not footnoted and the bibliography includes a few genealogical and antiquarian works that tend to mythologize the Swedes in Delaware, so despite Oestlund’s high standards, specific information from this latter work should perhaps be checked.

Please note that Hesselius’s paintings of the two chiefs have just been moved from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania to the Atwater-Kent Museum of Philadelphia, where they are on display. They are well reproduced in William Sawitzky, Catalogue Descriptive and Critical of the Paintings and Miniatures in The Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, 1942) and are discussed in John C. Ewers, “An Anthropologist looks at Early Pictures of North American Indians,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly 33 (1949): 223-35. James Logan’s remarks about Hesselius’s frankness as a painter are in Frederick B. Tolles, “A Contemporary Comment on Gustavus Hesselius,” Art Quarterly (Autumn, 1954): 271-73. A Google search will turn up standard Swedish biographical dictionaries that report on Gustavus Hesselius as on many of the characters described here. Hesselius’s will is reproduced in Francis de Sales Dundas, Dundas-Hesselius, (Maryland, 1938), 111-14; other legal documents including his naturalization are available online through the Maryland Archives. And a search of the digitalized Pennsylvania Gazette will produce a few more legal notices as well as advertisements for Hesselius’s many skills. Still more information on the three brothers in America and on the Swedes in the middle colonies, including an excellent sets of reference to sources in Sweden and here are in Carol Hoffecker et al., eds., New Sweden in America (Newark, Del., 1995), especially the essays by Staffan Brunius, Hans Norman, and Richard Waldron. Here will be found references to some of the classic narratives by Swedish priests and others describing the colony, many of which are available in English, most notably Israel Acrelius’s A History of New Sweden (original published in Sweden in 1759 but the William R. Reynolds translation from 1874–volume 11 in the Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania–is available from University Microfilms in Ann Arbor).

Andreas Hesselius’s “diary” of notes on America, immensely revealing of the man, is in English as The Journal of Andreas Hesselius, in Delaware History, 2 (1947), and in Swedish as Andreas Hesselii Anmaerkningar om Amerika, ed. by Nils Jacobsson (Uppsala, 1938). Sadly, Andreas’s bold proposals for reforming the American missions, which aimed straight at Jesper Svedberg’s heart, exist only in the original Old Swedish and printed in fraktur, in the original edition of Kort baerettelse om den Svenska kyrkios naervarande tilstoand I America (Norrkoeping, 1725). Be aware that some of the English translations omit a few pages of the originals. For a sharp contrast to Andreas, and a look at the kind of obedient missionary priest Svedberg preferred, see Andreas Sandels Dagbok, 1701-1743, ed. Frank Blomfelt, (Stockholm, 1988). Then there is the classic work of visiting naturalist Per/Peter Kalm, who spent a day with Gustavus at John Bartram’s farm near Philadelphia, Travels in North America, 2 vols., ed. Hanna Benson, original translation published 1937, Dover edition (New York, 1966).

Together these sources contain a surprising wealth of contemporary information by and about the brothers Hesselius. The unpublished records of the local Swedish community are widely scattered and there are no known collections of Hesselius family or personal papers. Susan Klepp has kindly provided information on the family from the Gloria Dei church records. The best single source of unpublished documents on the Swedes in the greater Philadelphia area is the Amandus Johnson Papers in the Balch Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Johnson transcribed many revealing documents in Swedish pertaining to the local Swedish community and translated a few. Lars Oestlund used these sources for his work on the Hesselius family and I have benefited from his detailed narrative based partly in them, but I still need to see the full Johnson Papers for myself. They were unavailable for some time because the Balch Collection was being moved into the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, but this week the HSP has at last been able to send me its description of the folders with copies of the contents of the most crucial folders. Johnson’s selections focus on the ministers and churches and so do not at any point dwell on the more secular Gustavus Hesselius. But these slim folders on Andreas and on Samuel Hesselius with miscellaneous documents in Swedish do have previously unnoticed information on Andreas, which confirms the picture of Andreas offered here. The other Jonsson papers are not as promising but on an impending visit I will check them all in case any yet undiscovered bits relevant to Gustavus still hide behind less likely folder descriptions. As for archival resources in Sweden, while I have spent considerable time in Swedish archives over the last thirty years, a recent summer visit to see archivist-friends to search their databases for Hesselius and to speak with Kathryn Carin Arnborg, and a subsequent exchange of correspondence with Staffan Brunius, have not been promising. There are some places to look that have not been searched thoroughly, but seeking Hesselius papers in Sweden beyond those found by Lars Oestlund would take a year of full-time enquiry with no sure rewards. Hopefully dissemination of this essay in Sweden will jog loose some finds. Hans Ling, formerly with Riksantikvarieaembetet, is about to publish further information on the Hesselius family in the online bulletin of the Swedish Colonial Society and has been of immeasurable help in improving this essay.

Staying on the Swedish end of things, Jesper Svedberg’s America Illuminata (1732), the bishop’s abbreviation of his long, somewhat differently titled manuscript Svecium Nova (see below), which virtually no one seems to have read, is available as America Illuminata, ed. Robert Murray, (Stockholm, 1985). And selections from Svedberg’s Levernebeskrivning, original 1729, are edited and modernized by Inge Jonsson, (Stockholm, 1960). These have just come in and Jonsson’s excellent introduction does not make Svedberg at all an attractive character. The correspondence between Andreas and the angry Svedberg is cited in Oestlund’s Andreas Hesselius, but much of it appears originally in Svedberg’s long 1727 manuscript, Svecium Nova seu America illuminata, original in the Library of Uppsala University (copy in the Amandus Jonsson Papers), on which his 1732 America Illuminatais based, and the correspondence in full is in the Cederhjelmska samlingen, Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek, B238. Samuel Hesselius’s collection of curious things and the early ethnographic world of seventeenth-and eighteenth-century Sweden are beautifully described in Staffan Brunius’s contributions to Med vaerlden I kappsaecken: samlingarnas vaeg till Etnografiska museet (Stockholm, 2002), a spectacular book available from the national Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm. Brunius has promised to keep me informed of his further progress with Samuel, the collector. For the botanical and zoological side of the same culture, see Yngve Loevegren’s first rate Naturaliekabinett I Sverige Under 1700-Talet (Lund, 1952). The Swedish husfoerhoer and the literacy campaign that made it work are the subjects of Egil Johannson’s life work, and can be sampled in English as Alphabeta Varia, Orality, Reading and Writing in the History of Literacy, ed. by Daniel Lindmark (Umea, 1988). See also Franklin Scott, Sweden: The Nation’s History, revised enlarged edition (Carbondale, 1988).

Private Martin is found in Ordinary Courage: The Revolutionary War Adventures of Joseph Plumb Martin (St. James, N.Y., 1993), Nicholas Collin in The Journal of Nicholas Collin, 1746-1831 (Philadelphia, 1936), key sections reproduced in Life in Early Philadelphia, ed. Susan Klepp and Billy Smith, (University Park, Pa., 1995). The Moravians are best seen through the remarkable new article by Aaron Fogleman, “Jesus is Female: The Moravian Challenge to the German communities of North America,” William and Mary Quarterly 60 (2) (April, 2003): 295-332. Fogleman and Paul Peukel of the Moravian archives in Herrnhut and Bethlehem have traced the materials on Hesselius for me through the letter book of Bishop Cammerhoff and the diary of Moravian missionary Abraham Reinke. The rest of this story will appear in Fogleman’s book on the Moravian challenge, in 2004. The painter’s son John Hesselius, still less well documented than his father though a portrait painter in pre-Revolutionary Virginia, can be encountered in “John Hesselius, Maryland Limner,” by Richard K. Doud, Winterthur Portfolio 5 (1969): 129-153. The gentrified and artistic world Hesselius’s daughters and descendants married into can be traced under the family name, and under “Wertmuller.”

The main effort to treat the origins of toleration in religiously diverse Pennsylvania is Stephen Longnecker’s Piety and Tolerance: Pennsylvania German Religion, 1700-1850 (Scarecrow Press, 1994), but in this thoughtful work the evidence for conflict and mistrust is almost as convincing as the evidence for mutual toleration until well past 1800.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.2 (January, 2004).

Kenneth A. Lockridge is professor of history at the University of Montana. His research interests have ranged widely through seventeenth- and eighteenth-century North Atlantic society.