Parenting for the “Rough Places” in Antebellum America

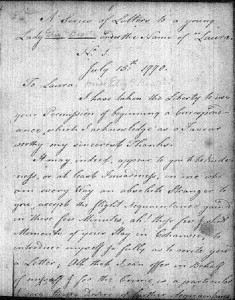

On June 2, 1833, her sixteenth wedding anniversary, Jane Minot Sedgwick opened a blank book and began journaling: “I have now been a widow seventeen months—my only remaining interest in life now is to watch over the characters of my children & aid their development.” Devastated by her husband Henry’s illness and death, she was gripped by the fear that the extensive caregiving she had provided her husband had caused her to neglect, and thus permanently damage, her children’s characters. She spent the next two decades chronicling her dedication to parenting theory and practice. Contemporary parenting manuals emphasized the importance of cultivating good character in children so they could resist and even avoid the temptations of the world, but Sedgwick articulated a vision of life-long parenting that went far beyond this. She aimed to cultivate mental and emotional “strength” in her children so they would be prepared to handle life’s unavoidable trials and sorrows. “[L]ife must be full of rough places,” challenging to rich and poor alike, but Jane hoped to raise children who might endure them, succeeding where she and their father had failed.

In any American bookstore, you’ll find abundant parenting literature that claims to define, through its advice, the shape, duration, and purpose of parenthood. These books have their antecedents in the parenting manuals and advice columns that flooded America in the early years of the nineteenth century, written by doctors, ministers, and middle-class women who claimed expertise. They argued that the rapid social changes of the early republic would lead to chaos in the absence of people of good character. Having the requisite good character allowed young people to marry well, socialize agreeably, form trustworthy business arrangements, and resist temptation in the dangerous world of Jacksonian capitalism. This parenting literature presented a new, intentional approach to childrearing that promised to facilitate safe, stable mobility for individuals and society, and assured parents–especially mothers–that with attention, care, and devotion, they could mold their children.

But Jane Minot Sedgwick was not a member of the rising middle class, anxious for her children to advance in the world. She wasn’t a farm wife facing the prospect of sending her son off to the city or her daughters off to the factory town without a supportive kin network. Thanks to an inheritance, she did not have to grapple with the difficult financial choices that other widows faced. She could–and did–choose to remain unmarried for the rest of her life. Yet Sedgwick’s journal reveals the ways in which antebellum parenting literature can obscure the struggles and goals of parenting that cut across class lines. Her journal is full of the anxiety, frustration, and grief of a woman traumatized by her husband’s reckless financial behavior, struggles with mental illness, and early death. It is dominated by the fear that she had failed her children in their crucial early years, and chronicles her attempts to right that wrong. Its usefulness as a source is not diminished by Sedgwick’s failure to write every day. Instead, in regularly taking stock of her children’s progress as the seasons changed, on holidays, and at her wedding anniversary, Sedgwick left behind a parenting journal that is both deeply and consistently reflective. Stretching from 1833 to 1853, well into the adult lives of her children, Sedgwick’s journal reminds us that this new intentional parenting could be a life-long process. Finally, its specific duration illuminates both the heady American faith in the perfectibility of the individual and the subsequent erosion of that faith, a central ideological shift in American thought manifested in the private anxieties of a widow raising four small children alone.

Jane Minot started her married life well-positioned to reign over the sort of happy family that domestic novels celebrated. The daughter of a prominent Boston family, she married Henry Dwight (Harry) Sedgwick, the third son of Federalist politician and judge Theodore Sedgwick, on June 3, 1817. They made their home in New York, where Harry practiced law. Their home was marked by loss when their first child, George, born in 1818, died a few weeks before Sedgwick gave birth to their second in the winter of 1821, a daughter they named Jane. Frances (Fanny) followed in 1822, then Henry (Hal) in 1824, and Louisa in 1826. It was then, with a house full of young and healthy children, that the Sedgwick family harmony began to dissolve. Harry increasingly alternated between stretches of deep depression and periods in which he had boundless energy and limitless faith in himself. As his sister Catharine noted: “He is continually making contracts on the most magnificent scale–he thinks the powers of his mind unbounded.” These magnificent yet reckless decisions nearly ruined the family’s finances, and he sent his wife and four children to live in his native Stockbridge. Noting his poor eyesight and agitated mental state, his wife and siblings urged him to step away from his work, but he refused, further animated by “the sense of injustice he feels from continual opposition.”

By the fall of 1828, his sister Catharine believed he “ought imme’y to be separated from his friends & put under restraint.” Sedgwick resisted, her husband having begged her in his calmer moments not to place him in the hands of a “mad Doctor.” When his condition failed to improve, she relented, consenting to his hospitalization only to see his mental and physical condition drastically deteriorate during months of treatment at McLean Asylum and the Hartford Retreat for the Insane. Bringing her husband home for good in 1830, she devoted herself to his care–reading to him, walking with him, and consoling him when he was awakened by nightmares of the asylum. He fell into a coma in the fall of 1831 and died a few days after Christmas. Through it all, Sedgwick’s in-laws noted with approval and pride, “her fortitude endures.”

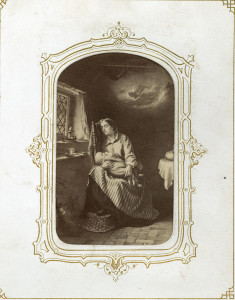

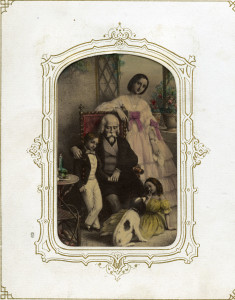

Antebellum women were told to aspire to being both perfect wives and perfect mothers. Sedgwick’s devotion to her husband during his illness had required sacrificing one goal to serve the other. When Harry had been under a doctor’s care, his wife often traveled to visit him, leaving her children in the care of in-laws. When Harry had come home, much as his children seemed to settle him and make him happy, Sedgwick had struggled to care for her ailing husband and manage her four young children at the same time, so she often sent the children to stay with family for weeks and even months at a time. Harry’s needs, she confessed to her brother-in-law Charles, “are so boundless that I must retrench somewhere.”

In the wake of her husband’s death, Sedgwick began her journal in 1833 by considering her failure to be both a wife and a mother to those who had depended on her: “. . . what a double responsibility falls upon me as a parent . . . I can never hope to fulfil all the duties that devolve upon me . . . my mind has so long been accustomed to attend only to him that I have been invisible to other cares—I have no longer an apology for neglecting anything which relates to the [care] of my children.” Before Harry’s illness, she wanted her children to have “warm & yet gentle character[s].” After his death, she wanted them to develop the personal strength necessary to endure life’s inevitable trials. Harry’s illness and death left her with the sole responsibility of parenting her children to adulthood and a new vision for what that adulthood must look like. She would try to raise Jane, Fanny, Hal, and Louisa to be stronger than their parents had been.

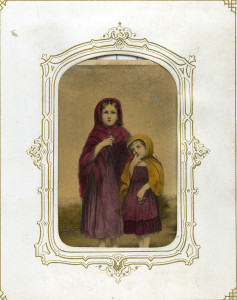

In order to track her children’s characters and “aid in their development,” Sedgwick began her journal with a frank assessment of each child’s current character. Little Jane, at twelve, “had the interior of a woman, a good deal of sense & discernment,” but little “practical usefulness” or regard for others. Ten-year-old Fanny was much the opposite: “affectionate but timid in her disposition” and deeply attached to her mother. Hal, “a lovely looking boy” of eight, was full of what his mother termed “spirit,” though spoiled and with an “inveterate propensity for fun.” Louisa, at six, was “less conspicuous than the other children,” but her mother felt she had “the sweetest disposition of the whole four” and “good common sense.”

Initially, she sought to catch her children up as quickly as possible, and her approach reflects much of what we see in the advice literature of the time. She sought good educational opportunities for her children whenever possible. She sent Jane to Boston for schooling soon after her husband’s death, and sent Hal to live with his Aunt Elizabeth and Uncle Charles in Lenox “for the benefit of Mr. Parker’s instruction in Latin.” Fanny and Louisa both went to Aunt Elizabeth’s school, and then to Mr. Parker’s with their brother, before he departed for Harvard. When her daughters were at home in Stockbridge, Sedgwick employed young women to teach them drawing and piano. She did not completely abandon the education of her children to teachers, as cautioned against by parenting literature, but rather gave her daughters chores at home to reinforce their lessons and make them industrious. The constant parade of visitors to whom the children were exposed–Channings and Follens, Harriet Martineau, Fanny Kemble, and Horace Mann–testify to Sedgwick’s commitment to learning by example, a central tenet of contemporary parenting advice.

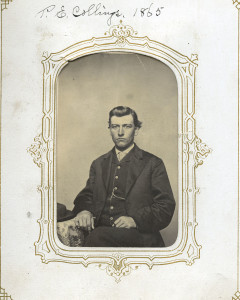

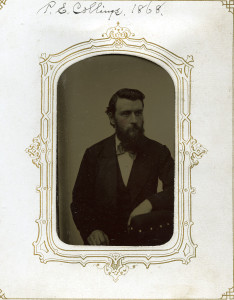

Over the course of the journal, distinct visions of male and female adulthood emerged, antebellum gender roles abstracted through the prism of Sedgwick’s own suffering. In her efforts to mold her children into the adults she believed they needed to be, we see anxieties and worries about childrearing deeper and more fundamental than what contemporary advice literature addressed. Sedgwick was concerned, for instance, that Hal remained more interested in fun than work, a fairly common concern at the time. Parenting literature advised parents to curb greedy and impulsive behavior in children, often warning them of the dangers that would face their children–and their sons in particular–in young adulthood: alcohol, tobacco, sex, and gambling. Sedgwick showed little concern over her son’s fondness for tobacco, and none at all over his fondness for alcohol, a fondness that she and her daughters shared. Instead, her writing reflects her specific fear that Hal might take after his father, whose impulsive tendencies, to her mind, led him to make risky and disastrous financial decisions, and rendered him incapable of reflection and improvement in the face of failure, which ultimately trapped him in a deepening mental and emotional instability that claimed his life. Raising her son to avoid greed, temptation, and impulsive behavior was not simply a matter of saving his reputation, or even his soul; it was a matter of saving his mind and ultimately his life, and simply teaching him to avoid drinking and gambling was insufficient. If Hal could display true fortitude in the face of life’s trials, enduring them and learning from them in ways his father had failed to do, indulging in a glass or three of wine with dinner posed little danger.

Her experiences with her husband and fears for her son also shaped how she assessed her daughters’ characters and planned for their futures. Sedgwick worried that her daughter Jane–strong and independent–lacked warmth, and that Fanny–warm and sympathetic–lacked strength. Before their marriage, Harry had promised his fiancée he would never take financial risks, but he had, and ultimately left his widow to carry on alone. As a result, Sedgwick sought to raise her three daughters to have the fortitude to endure the suffering and the warmth to endure the pain that resulted from the poor choices of the men who ultimately controlled their fortunes. Status and financial security had not been enough to dissuade her husband from making risky decisions, nor had they been enough to shield her from the painful effects of his failures. In light of this, Sedgwick believed her daughters needed to develop strength their mother believed that she herself lacked.

Given the depth of her fear for her children’s futures, it is perhaps unsurprising that she was often pessimistic about their progress, especially that of her daughters. She consistently lamented young Jane’s willfulness, Fanny’s clinginess, and Louisa’s lack of industry. Hal received slightly more praise, as his longer formal schooling provided his mother with external evaluation from his teachers and professors. In general, though, Sedgwick continued to see in her children the worrisome flaws she had identified early in life, and expressed her frustration both at the persistence of these flaws and her inability correct them.

Even rarer than Sedgwick’s praise for her children was praise for herself. She believed her children’s moral failings to be her fault, and she took herself to task for not knowing how to change them: “Of all my trials but one–the impossibility of influencing my children as I wish is by far the greatest.” Over and over, she catalogued her failures and errors: “I have not been in all respects a judicious mother,” “I have not taught them self-denial,” “perhaps I expect too much at once.”

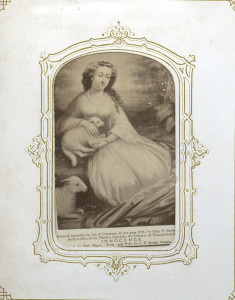

Authors of parenting advice like Jane’s sister-in-law Elizabeth Sedgwick insisted that if a mother was sufficiently self-sacrificing and devoted to her children, “[s]he can create in them any taste, form in them almost any habits of occupation…can bend them almost at will.” This was a gift that every mother had, if she would embrace it: “she was born to train the sons and daughters of men for this world, and for the world to come.” In the privacy of her journal, Jane Sedgwick admitted that others “held in less estimation in society” –those for whom parenting manuals were purportedly written–seemed to have more of this “gift” than she did, but nowhere in the first ten years of her journal did she seriously question the central tenets of these manuals: that human character, especially when young, was moldable and perfectible, and that mothers had the ability and obligation to mold and perfect. Reflecting on earlier journal entries in which she expressed “discouraging views” of her children, Sedgwick was wracked with guilt over her own failings. This, in turn, prompted entries in which she endeavored to “bear testimony” to the progress in her children’s characters. Even then, she noted intellectual and social progress, but never the strength of character she believed she should have been able to cultivate.

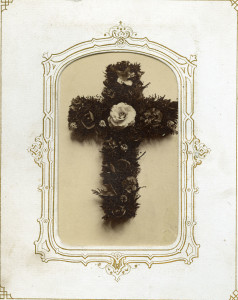

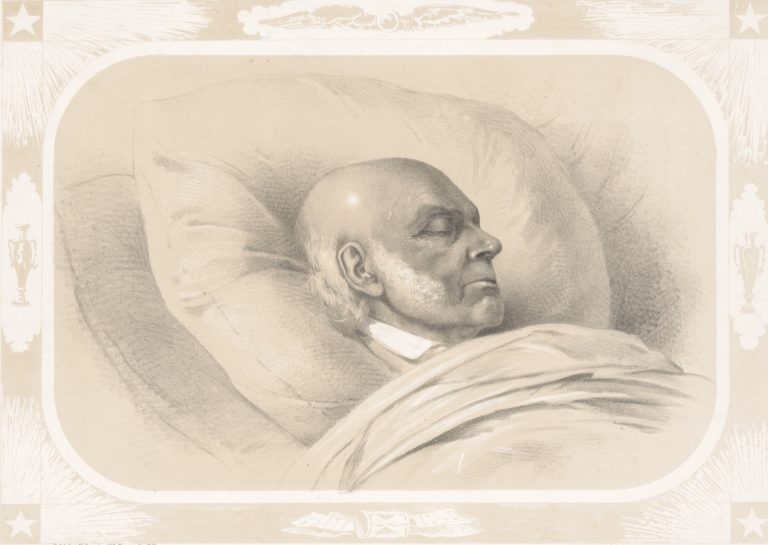

Only one entry each year was consistently positive–Sedgwick’s Thanksgiving Day record of gratitude for “a healthy family competence”–but even that tradition was short-lived. Following the suicide of their cousin Charlie and the death of their Uncle Robert in the spring and summer, Jane, Fanny, and Louisa all fell ill with typhoid fever in the fall of 1841. The older two recovered, but Louisa died on October 13th, just a few weeks before her fifteenth birthday. Relatives praised Fanny and Jane, who were pensive and calm in the wake of their sister’s death. One aunt singled out Hal, who was “grave, but has more elasticity than any of them,” though his mother privately recorded seeing his “agony over the dead body of his sister & [hearing] his bitter lamentations.”

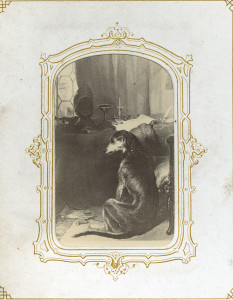

To her sister-in-law Catharine, Jane was “the ultimate model of strength in suffering” in the wake of her daughter’s death: “calm, submissive, & thoughtful for others.” In the privacy of her journal, however, Sedgwick expressed the depth of her grief and regret in the weeks following her Louisa’s death, beginning by copying over Dickens’ description of Little Nell’s death. Then, in November 1841, in the longest single entry in her journals, she memorialized her daughter, beginning with the circumstances of her birth: “Louisa was born during a most troubled season of my married life–just after her father’s great controversy which commenced his insanity…I was too much agitated by her father’s troubles to be able to nurse my child and I was so fortunate as to have her infancy most carefully watched over by the excellent Mammy Royce…her father’s disease increasing as she grew older, I was obliged to leave her very much to the care of Miss Speakman.”

Contemporary parenting experts argued that breastfeeding was vital to familial bonding–here, Sedgwick pointed to her failure to provide, and it seems, blamed her early neglect for her daughter’s fate. Moreover, these experts believed parental involvement more broadly was most vital in the early years of life, when children were most plastic; Elizabeth Sedgwick believed a mother’s “training of the immortal spirit” of her child must begin “[a]s soon as it is capable of comprehension,” and Reverend John S. C. Abbot argued in his 1844 work The Mother at Home that “the first six or seven years decide the character” that will follow a child to adulthood. Yet as a result of her father’s illness, Louisa had received the least maternal attention of any of Sedgwick’s children.

Sedgwick noted that, even with this early deprivation, her daughter’s “moral qualities . . . marked her individuality.” Every example she produced highlighted Louisa’s willingness to help others who were burdened with grief and illness, and her ability to do so without sacrificing other important obligations or her calm, optimistic disposition. Despite her own perceived failures as a parent, Sedgwick believed Louisa had embodied that much hoped-for strength of character that her parents had lacked. Even as she mourned her “sweet devoted child,” Sedgwick looked to the effects of Louisa’s death on her siblings: “if I could certainly feel that this dreadful affliction is to improve the mixture of my remaining children my sorrow would not be too despairing in its character.”

After a two year gap, Sedgwick resumed her journal after settling into New York apartments for the winter of 1843. She had come to New York solely for the sake of her children: to watch over Harry in his young professional life, to be near a doctor for Fanny, who had inherited her father’s eye problems, and to provide “the variety & excitement of a City life to check [young Jane’s] constitutional melancholy.” Yet she privately wondered whether her job as a parent was over: “I have no longer any direct control over them, neither have I much influence… my work in life is pretty much through . . . I have failed in my power to influence their minds.” Despite feeling this “sense of uselessness,” however, she could not stop trying to shape her children’s characters.

In these years, Sedgwick turned to religion, hoping her children might experience “regeneration” through the sermons of Henry Whitney Bellows or William Henry Channing. To her frustration, it seemed clear that they listened attentively yet “made no personal application of it.” She was most concerned about her son’s moral compass. While he was “governed by principle,” she desperately hoped he would “manifest a religious sentiment,” which she believed would be “the only security for the preservation of his present virtues.” But what could she do? Could she actually make them change?

Much as Hal’s adult flaws mirrored his childhood (and his father’s) troubles, Jane and Fanny were but more mature versions of their childhood selves. “Jane,” her mother noted, “has led rather an eccentric course from her love of independence & her desire to obtain useful occupation,” but had improved slightly in her “consideration for others.” Her strength and independence had increased, but some warmth had crept in. Fanny remained affectionate but timid, but had endured great suffering as a result of her eyes. Her mother proudly recorded that “she has exhibited great courage & fortitude” in the face of such hardship.

With her children grown, Jane Minot Sedgwick wondered not only whether they were still moldable, but also the extent to which they ever had been. In 1834, in her early widowhood, she viewed her children as “much too undisciplined for their age” and attributed this to her failure to be a mother to them while her husband was ill: “I presume I have made a mistake in the early management of them.” In 1844, three years after Louisa’s death, Sedgwick still wondered if there was a “deeper anguish than the feeling of utter inability to guide yr own offspring in what seems to you the essential paths for their virtue & happiness,” confessing in her journal: “this sentiment is so strong with me that I almost regret being a mother.” Yet she now recognized that Louisa, the child most deprived of parental attention in her formative years, had developed the exact character her mother desired. As a result, Sedgwick began to believe that the difficulties in guiding her older children were not due to a lack of effort to mold them, but because “the mould in which they are formed is different from mine,” and from their youngest sister’s.

Sedgwick’s evolving ideas about her children’s natures and her ability to shape them reflected an emerging American skepticism of the perfectibility of the individual and society at large, and an increasing emphasis on the determining power of innate characteristics. This shift in thinking allowed Sedgwick to take a new approach to parenting, one in which she considered not what was objectively “best,” but rather what was best for each individual child. Despite her concern over their fundamental natures, she hoped that “there may yet be elements in their characters which may result in something better than I anticipate.” When her daughter Jane was determined to venture south to work as a teacher, Sedgwick supported her when few others did; she likewise later supported Jane’s conversion to Catholicism. Further, she sent Jane and Hal to Europe together for six months with no other chaperones. She disliked the idea of foreign travel, but recognized her children were different than she was. She also consented to Fanny’s marriage with Alexander Watts, a beau “whose virtues are his only possession[.]” Though worried her daughter’s own virtues would be tested by this marriage, Sedgwick believed she had made the right decision “for [her] child’s happiness.” Though Sedgwick still emphasized the importance of strength, she accepted that strength might manifest itself differently in her children.

In December 1850, Fanny was struck by “derangement,” and Sedgwick expressed her deepest fears that history would repeat itself: “Am I called to go through the same agonies with my child which I endured for her father?” Sedgwick’s only consolation was the belief that her life of suffering had “deadened [her] sensibilities,” which might help her remain strong. Yet where she and her husband had failed twenty years earlier, she and her daughter persevered. Fanny emerged from her “mental malady,” seen through her illness by her mother. Sedgwick proudly recorded that she had both attended a family wedding and visited the “excellent city infirmary” at Five Points during her daughter’s illness, correctly balancing her social and familial obligations. Despite Sedgwick’s belief that she had failed to strengthen Fanny’s weak character in childhood, her daughter had endured this trial, and Sedgwick herself had parented her through it with the strength of character she felt she had lacked twenty-five years earlier.

In May 1851, Sedgwick noted that her children were all happy and “upright.” Given the “rough places” they had passed through, this was all she could have hoped for. In February 1853, she picked up the pen for the last time: “I must note a record of my dear little grandson… He is now 13 months old.” What had prompted this note? Her daughter Fanny was still an invalid, and “her heart [will] probably never be light again, but the smiles of her lovely boy give her a pure joy.” Jane Sedgwick believed that parenthood was about raising children to endure life’s trials, and her perceived failure at the task at itself seemed like a trial she herself could not endure. Yet in observing her own child become a parent, Sedgwick closed her journal by acknowledging that parenthood could also be the joy that eased life’s inescapable suffering.

Further Reading

All direct quotes come from Jane Sedgwick’s journals, the letters of Catharine Maria Sedgwick, and the letters of Louisa Davis Minot, which can be found in the Sedgwick Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society, or from Elizabeth Sedgwick, “A Plea For Children” American Ladies’ Magazine, February 1835. The classic examination of the antebellum emphasis on character is Karen Halttunen’s Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven, 1982). For a recent exploration of nineteenth-century parenting literature, see Emily Casey’s 2011 dissertation “The Mightiest Influence on Earth: Americans’ Emerging Conception of Parenthood, 1820-1880.” On motherhood and female childrearing, see Ruth H. Bloch, “American Feminine Ideals in Transition: The Rise of the Moral Mother, 1785-1815,” Feminist Studies 4:2 (June 1978): 100-126; Richard A. Meckel, “Educating a Ministry of Mothers: Evangelical Maternal Associations, 1815-1860,” Journal of the Early Republic 2:4 (Winter 1982): 403-423; and Lee Chambers-Schiller, “‘Woman Is Born to Love’: The Maiden Aunt as Maternal Figure in Ante-Bellum Literature,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 10:1 (1988): 34-43; Nora Doyle, “‘The Highest Pleasure of Which Woman’s Nature Is Capable’: Breast-Feeding and the Sentimental Maternal Ideal in America, 1750-1860,” The Journal of American History 97:4 (March 2011): 958-973; and Paula Fass, The End of American Childhood: A History of Parenting from Life on the Frontier to the Managed Child (Princeton, 2016). On maternal grief, see Sylvia D. Hoffert “‘A Very Peculiar Sorrow’: Attitudes Toward Infant Death in the Urban Northeast, 1800-1860,” American Quarterly 39:4 (Winter, 1987): 601-616 and Lucia McMahon, “‘So Truly Afflicting and Distressing to Me His Sorrowing Mother’: Expressions of Maternal Grief in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” Journal of the Early Republic 32:1 (Spring 2012): 27-60.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jackie Penny at the American Antiquarian Society for her help finding and reproducing the images in this piece. Thanks also to Allison Horrocks for her thoughts on early drafts, Amy Sopcak-Joseph for our discussions of women and “fortitude,” and William Black for fixing one stubborn sentence.

This article originally appeared in issue 18.2 (Spring, 2018).

Erin Bartram is an independent scholar; she completed her PhD at the University of Connecticut in 2015. She is working on a book project on the possibilities and limitations of female self-culture in nineteenth-century America. Her work has appeared in U.S. Catholic Historian, the Washington Post, and the Chronicle of Higher Education. She is a regular contributor to the blog Teaching U.S. History, and writes on history, pedagogy, and higher education on at www.erinbartram.com. You can find her on Twitter @erin_bartram.