Dancing the “Republican Two-Step” with Copyrights, Patents, and Corporations

In this issue of “Common Reading,” we bring you a conversation about an important aspect of our modern predicament, as seen through historical and anthropological lenses. Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, an anthropologist at UNC-Chapel Hill, and Mark Peterson, a historian at UC-Berkeley and editor of this column, discuss two books, one new and one old, and their collective implications for our world, in which ever larger corporations, with unfathomably sophisticated tools, are engrossing and enclosing ever more of the collective wisdom and potential knowledge of our societies.

Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld:

Several years ago, in the mountains of Ecuador, I watched as burning tires melted doughnut-shaped ruts into the asphalt of the Pan American Highway. Bands of protestors stood by, steeling themselves for the arrival of soldiers. In March 2006, Andean natives had rallied to fight a free trade agreement between Ecuador and the United States. After ten days of stonewalling the activists’ demands, the national government declared martial law. In the town of Peguche, leaders called for residents to radicalize the strike (fig. 1). On a side street near their main blockade, teenage boys jabbed sharpened re-bar between the cobbles, prying up fist sized rocks. Further up the road, women sat on a curb surrounded by empty mineral water bottles and plastic jugs of gasoline, tearing white sheets into long, even strips—wicks for their anarchical bombs. As the strike accelerated toward its climax, the national media focused with increasing anger on one question: what were native peoples so concerned about? The details of the treaty were arcane; the consequence for native careers seemed remote.

Many protestors admitted they did not know the details. What they feared, though, was that their subsistence crops, their medicinal plants, and their ecological knowledge all were at risk. U.S. companies empowered by the treaty struck native peoples as an imminent threat, poised to convert Andean talents in farming and healing into corporate property. A pamphlet circulated at the Peguche blockade, insisting that with the free trade agreement, “indigenous people and peasants will be obligated to mono-culture, to use seeds treated in the laboratories of the United States (transgenetic).” Protest banners proclaimed, “Corn, Wheat, Potatoes are our Life: Out with the Treaty” (fig. 2). Put simply, with stones, Molotov cocktails, steel bars, and blockades, Indians were arming themselves for war against corporations bearing U.S. copyright and patent laws.

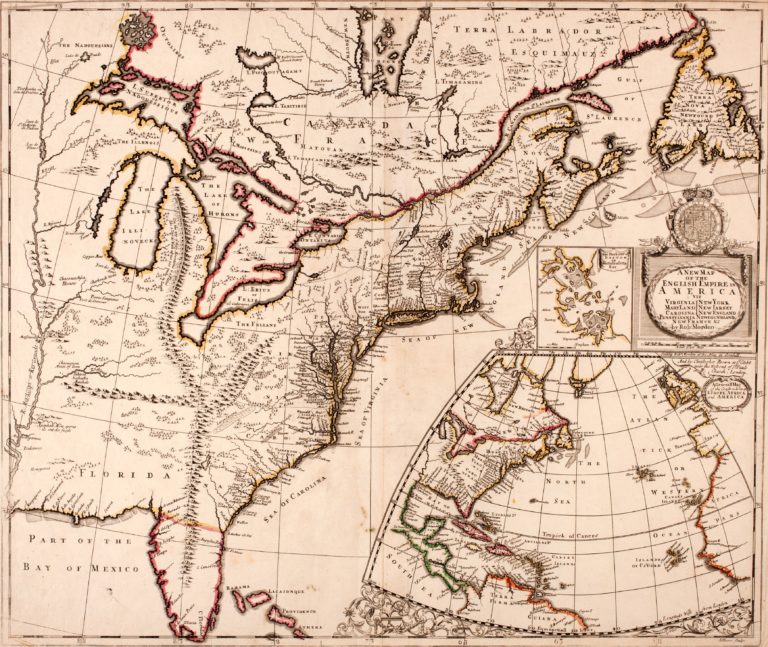

In Common as Air, Lewis Hyde sketches how we got here. Since World War II industrial economies have remade themselves as “knowledge economies.” Studios and laboratories have supplanted shop floors as the source of wealth. Monsanto, Pfizer, Microsoft, and Disney stake their future on the “know-how behind the goods” rather than material goods themselves. With the new technology of digital copying and the Internet, inventors can sell and resell the same idea infinitely and at little cost. And as the returns on capital multiply, the United States government has proved a willing ally in defending corporate ownership of ideas, aggressively exporting “knowledge laws” and forcing trading partners into compliance. The backlash against these American laws and their increasingly global reach raises a question: does this regime of intellectual property law represent something intrinsic about the United States—not just its economy, but its culture and society? After all, copyright law is rooted in the U.S. Constitution. Did the founders of the republic incline its citizens toward a commercial enclosure of knowledge and creativity?

In a wonderful exploration of this problem, Hyde tacks back and forth between political philosophies of James Madison, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, on one hand, and instructive moments of American creativity, on the other: Ben Franklin’s electrical experiments, Bob Dylan’s songsmithing, and Martin Luther King’s sermon writing. Seeking a language that could stand as an alternative to “exclusive copyright,” “private ownership,” and “intellectual property,” Hyde joins other writers who turn “to the old idea of ‘the commons’ as a way to approach the collective side of ownership.” The commons discourse turns out to be archaic and arcane. Hyde tells of “estovers,” “stinting,” and “beating the bounds.” The point, though, is not really to argue that the Founding Fathers conceived of science and invention as akin to harvesting in wild wood and shared fields. Rather, through his exploration of the commons, Hyde gains a set of heuristics—questions about communal duty, about the limits of exploitation, and about individual liberty—that guide his inquiry into early American writings on copyright and monopolies in commerce.

Hyde states somewhat drily that for America’s revolutionaries, “intellectual property is ultimately a republican estate. It is the intangible equivalent of the tangible res publicae (roads, bridges, harbors) of the Republic itself.” His meditation on the commons, though, reveals that estate as a dynamic composite of public duty, freedom, and uncharted lands. The commoners who gather in their perambulations to knock down encroaching fences, who hold themselves back from overgrazing their shared property, and who preserve the untamed wastes along with their plowed fields strike a balance between private affairs and a shared space of possibility.

Mark Peterson:

But isn’t the commons, in both its tangible sense as shared material resources, as well as its metaphorical sense of intellectual or knowledge resources, something more than just “possibility?” Doesn’t the traditional idea of the commons also have something to do with preserving a margin of security, or even a modest degree of comfort, in a hostile world? The firewood to be gleaned or the food to be gathered on the commons gave peasants comfort or warmth beyond what their own meager individual resources might yield, comfort they relied on as part of their due for the service they performed for their lord and their neighbors. Couldn’t the same be said of the right to sing a traditional song, or to use a clever new tool for getting work done a bit faster? To enclose these through copyright or patent is to rob someone of real comfort and security, not just possibility.

RCM:

Yes, and the tangible value of these resources, intellectual or otherwise, comes through in Hyde’s discussion of the equally tangible duties, burdens, and costs required to maintain the commons. Throughout much of the book, Hyde’s central concern is the interdependence of private interests and civic obligation. He tracks the ways that eighteenth-century thinkers proposed a structure of law, and assumed a manner of comportment, “such that the public domain might inherit from the private.” The “Republican Two-Step” he comes to call it, “first autonomy, then service.” The model here is a life career in which one matures from a partial, individualized, private self to the full dignity of a public life. Hyde uses the life course of the young John Adams to show the meaning of this process. Upon the death of his father, Adams inherited a farm in Braintree, Massachusetts, becoming for the first time a freeholder, a taxpayer, and a voter at town meetings. To Adams’ initial dismay, the town elders also expected him to become a bridge builder, standing him to be elected as Braintree’s surveyor of highways. Hyde writes that Adams’ protests as to his ignorance about the bridges mattered little; “everyone had to take a turn at town offices.” With property comes duty—not as an optional act of charity, but a requirement, intrinsic to the nature of property ownership within the community. And since the corporate towns of Massachusetts were the ultimate source of that property, the bodies that granted land in fee simple to the original inhabitants, then the town had every right to set the terms of property ownership.

This lesson would be generalized to knowledge and learning. If the drafters of the Constitution conceded the utility of granting monopoly privileges to authors and inventors, they saw this privilege as a limited one. With patents and copyrights come service; first private gain, then public use. Hyde quotes Jefferson: “certainly an inventor ought to be allowed a right to the benefit of his invention for some certain time. It is equally certain it ought not to be perpetual.” Jefferson’s certainty rested in part on a faith that “ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition.” It also lay in the conviction that “citizens can never be truly self-governing until they have a lively public sphere, a free flow of knowledge, religious liberty, and so on.” Citizens cannot passively await the appearance of a public sphere; they are duty-bound to create this cultural commons with their contributions.

All the talk of duty, service and obligation, though, risks misrepresenting the public sphere as only a burden, where virtue overshadows joy, morality tops creativity. Yet, as he builds his case, Hyde keeps his eye on all that is untamed, abundant, accidental, and random within a commons. It is these same qualities that set the potential for inventiveness in a knowledge commons. Hyde begins with Locke. The philosopher had observed that nature is a “wild common” lacking the improving hand of man (23). A vision of uncultivated “wastes” inspired dreams of plentitude; the commons appeared to Locke and others to be a primordial “commodious world.” Contemporary anthropologists (and the ancient peasantry) might dispute Locke’s vision of abundance on prosaic, ecological grounds. Typically, wastes remained uncultivated commons because the poverty of their soils and treacherousness of their slopes rewarded individual labor so meagerly. Humans traveled lightly on this land, passing by occasionally to harvest what they could, neglecting it at other times, and allowing the survival of wild plants and feral animals.

MP:

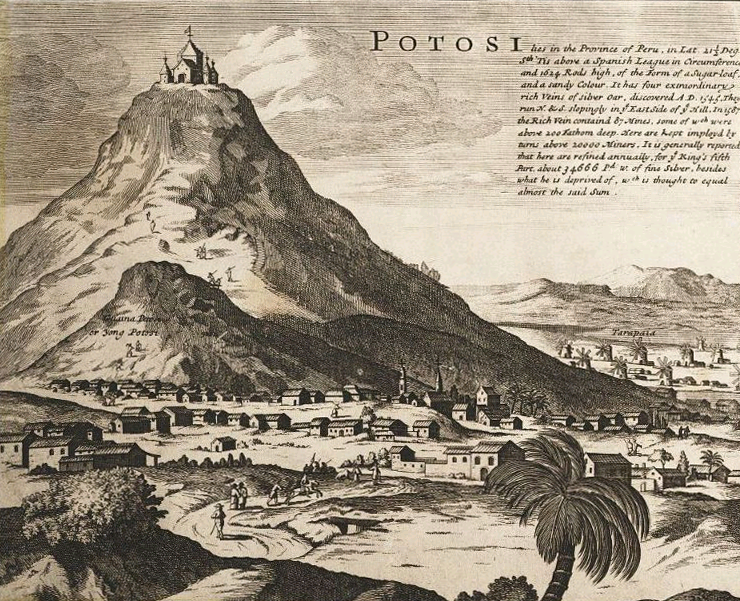

So, in an ecological sense, it may seem surprising that Massachusetts turned out to be one of the places in the Americas where “commons” practices, and a “commonwealth” form of government, took hold with great tenacity. Compared to Mexico, Peru or Hispaniola, where natural barriers of mountains, high desert and rainforest resisted farming and preserved wildness, New England’s ecology easily sustained a comfortable human existence. But from an imperial point of view, the strength of commons and commonwealth in Massachusetts is no surprise at all. Peru, Mexico, and the Caribbean all yielded commodities of incredible value to Europeans—gold, silver, sugar—and so the various conquistadors seized and enclosed these territories as rapidly as they could. Massachusetts was a “wasteland” from this perspective, yielding almost nothing that England lacked. Oliver Cromwell called it “poor, cold, and useless.” Yes, the indigenous peoples or English colonists could subsist comfortably enough in its temperate climate, but there was nothing there that any self-respecting imperialist really wanted to enclose. That’s why, as late as 1630, it was still open to middling Puritan dissenters and their utopian dreams of a godly commonwealth.

RCM:

Although Hyde does not take up the ecology of the commons with this kind of specificity, he does have a sense for humans’ complicity within it. The collective defense of the commons—the beating of the bounds, the destruction of encroachments, stinting—promoted its generative wildness by holding the extractive technologies of market and polity in check. The practice of the commons removed fences and undid covert investments. When strongly held, such habits make possible “the practice of the wild, one whose first condition is the simple freedom to wander out, unimpeded, beyond the usual understanding and utterance.” Enter a living commons and have the chance to “contact with what lies outside our knowledge.”

All this consideration of the “practice of the wild” may divert readers away from copyright, obligation, and the public domain, but Hyde circles back to these concerns when he takes up the topic of liberty and what it meant to men like Benjamin Franklin, Tom Paine, and Noah Webster. Again, Hyde reflects on the freedoms afforded in an ancient England of commons and manorial estates. Here a model of liberated action could be found in the “fee simple,” or “allodial,” holdings, of those families fortunate enough to hold their estate without having to pay the vassal’s duty to the lord, a model that English colonists readily translated to North America, where there were no lords to pay, or where the lords were far removed, an ocean away from the settlers. But if the fee simple estate promised independence, it did not end an expectation of service. Rather, for Puritan thinkers, allodial estates relocated duty to the “conscience of the autonomous citizen.” Freedom becomes a social and moral condition, not a mere releasing of a person from bondage. Indeed, eighteenth-century writers equated individual liberty with licentiousness. It was “the freedom of beasts rather than that of human beings. Humanliberty, on the other hand carried with it an obligation to serve the public sphere.”

It is in this public condition, the free person’s necessary engagement with public life, that Hyde locates a deeper source of intellectual and creative liberation. The first step lies in personal effacement. Inventors, writers, and scientists stand to gain by disidentifying with their ideas, restricting their own claims on them, and allowing them the liberty to circulate. As Franklin wrote in the midst of the Revolution, “I have never entered into any Controversy in defence of my philosophical Opinions; I leave them to take their Chance in the World.” By stepping back from his or her creation, the public-minded citizen draws others into the debate. What might have been limited, private opinion instead becomes a public proposition about the world, a topic of shared conversation.

The second step toward freedom lies in joining others. Here Hyde jumps ahead to the twentieth century and engages the revolutionaries of the 1960s. As a teenager, for example, Bob Dylan immersed himself in the songs and lyrics of others, spending weeks listening repeatedly to records of Robert Johnson, copying his words on scraps of paper, listening to Woody Guthrie albums as if in a trance, playing Bob Nolan’s “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” in his head constantly. Losing himself in the work of someone like Woody Guthrie, Dylan realized that he was “feeling more like myself than ever before.” In a similar vein, the Reverend Martin Luther King assembled the “I Have a Dream Speech” from a host of thinkers: Gandhi’s ideas of soul force, James Baldwin’s and Malcolm X’s metaphors of promissory notes turning to bad checks, Archibald Carey’s refrain “Let freedom ring,” which Carey used in his 1952 address to the Republican National Convention. Not only did the power of the public sphere shine in the lyrics of Dylan and the speeches of King; that sphere itself became transformed through these men. In Hyde’s telling, the generative force of people such as Dylan and King grew from the way they were freed to travel in an ungated American cultural commons and the way they exercised their freedom in a form of public service, as dutiful members of a collective. Woody Guthrie’s work, itself borrowed and remade from countless earlier sources, is more powerful today than it was in 1960 because Bob Dylan also borrowed from it and shared it, making it something new yet again.

This conjuncture of service, freedom, knowledge, and the public sphere is what makes the lesson of eighteenth-century American revolutionaries matter for twenty-first-century Andean rebels. Assembled at the barricades in 2006, highland Kichwa people were not just fighting free trade laws. The activists, leaders, pamphleteers, and bomb makers were seeking to open a new Indian future in the contemporary world. If part of the struggle was political, aiming for increasing autonomy, another part of it was cultural, aiming to enhance their creative power. One of the most pernicious marks of colonization is the consignment of Andean knowledge to the realm of the local, the traditional, and ultimately the past. Indeed, domination entails the persistent interference with the knowledge-making of the colonized. The Stamp Act that forced residents of the North American colonies to pay more for a college degree than those in Britain is but one small example of the way in which power inheres in barring subjects from interaction and intellectual engagement, in forcing upon them a parochial isolation.

Andean leaders are well aware of this. In the course of the modern indigenous movement, they have established a university, created a scholarly journal, and built Websites. They are pushing for an Indian public sphere, for the growth and application of native knowledge. In Common As Air, Hyde spells out both the requisites and rewards entailed in making a durable cultural commons a reality.

MP:

But lest we underestimate what Hyde and the Andean protestors are up against, consider a still more recent set of events. On August 15, 2011, Google purchased Motorola Mobility for $12,500,000,000, at a price that was 63 percent higher per share than the going rate on the stock market. Why? Not because Google wants to become a manufacturer of cell phones. It’s all about the patents.

Google’s major corporate competitors in the business of capturing and shaping the world’s time and attention, Apple and Microsoft, recently acquired thousands of patents for the technological devices and know-how most useful in this cunning art. Not to be left standing out in the dwindling technological open fields, Google jumped into the enclosure game with its pricey purchase, buying Motorola’s 17,000 patents in order to rake in and fence off as much of the knowledge domain as possible. If Andean leaders in their new universities are going to put something of value on their Websites, Google is going to know about it, and figure out some way to extract advertising money from the process of directing anyone’s attention toward it.

When early American leaders, in imitation of English precedents, wrote patent and copyright powers into the United States Constitution, they presumably did not envision the possibility of a “person” who might acquire 17,000 patents in a single stroke with a mountain of money, a “person” whose lifespan might be perpetual, or a “person” with no real social relationships or public responsibilities. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution speaks of “Authors and Inventors,” not corporations, as the potential beneficiaries when it grants Congress the express power to pass laws that will secure “for limited Times … the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” But the Constitution nowhere recognizes or makes any specific provisions for the existence of corporations, which are the creations of legislatures in the individual states.

In an ordinary human life span of three score years and ten, a citizen of the republic (a John Adams or a Benjamin Franklin) might be expected to have an intrinsic sense of when the moment arrives for step one—individual accumulation—to cease, or at least slow down, and step two—public service—to commence or accelerate, in the performance of Hyde’s “Republican Two-Step.” But if a corporate “person” can live forever, with no responsibilities to the public and no social liabilities, and can find no limit to its accumulative capacities and desires, then why should it ever feel the need to move from step one to step two?

By toggling back and forth between the eighteenth century and nowadays, Lewis Hyde’s Common as Airskips across the era in which corporate personhood took on its modern form, and thus underplays an essential element of this larger story. To fill in this gap, let me turn to an older work, Oscar and Mary Flug Handlin’s classic study, Commonwealth (1947), written in a different era but for purposes strikingly similar to those of Lewis Hyde.

The Handlins, like Hyde, wanted to know how we got here. Their project was sponsored by the Committee on Research in Economic History, a New Deal-era endeavor to explore the historical relationship between government and economy. As the Handlins described it in the preface to their revised edition, “the guiding question when the research began was an assessment of the extent to which laissez faire was important in the American economy before 1860.” At the time they began their project, it was widely assumed that prior to the New Deal, government had played little part in the American economy.

What the Handlins found was strikingly different. By studying the role of the state in economic affairs in Massachusetts, they came to the initial conclusion that “laissez faire” was not even a relevant term in the commonwealth’s early history. The directing hand of the General Court was so prevalent, and so unquestioned, in countless aspects of economic life as to make “discussion of the development of economic policy in terms of laissez faire hardly meaningful… The hundreds of laws regulating the flow of water to mills, setting the time for the taking of alewives or providing for the inspection of potash were a challenge. What was their meaning? Why did men enact them? What function did they serve?” To answer these questions, the Handlins investigated the history of corporations, the economic institution of the early republic most closely associated with public policy.

This is precisely the point where the Handlins’ subject coincides with Lewis Hyde’s. For, like patent and copyright law, the corporation in the early republic was initially designed to perform an intricate dance, a variation of the Republican Two-Step. If patents and copyrights were meant to benefit individuals immediately and the public in the long run, the case with corporations would be roughly the opposite. The public would immediately benefit from the legislature’s creation of corporations, because corporations would take on useful tasks that lay beyond the means of any individual to perform, and which the state lacked the resources to manage on its own.

To offset the risks of such large ventures, the commonwealth could grant special privileges to corporations, such as unlimited duration, monopoly privileges, and the right to sell shares with limited liability to investors. The net result would be a public good—a reliable bridge across the Charles River, for instance—at minimal cost to the citizens at large. Eventually, the corporate undertakers and their investors might profit from the venture, but only if it actually provided the intended public good.

RCM:

Of course, to this day in the United States, do-gooders of all stripes form corporations, albeit non-profit ones, to carry their cause forward. The corporation in the U.S. in fact seems to take on a bewildering number of forms, from a small-town youth soccer program to an international software company. Yet for all the differences, each seems to share a fundamental quality: that of being a private initiative that stands apart from and perhaps in opposition to the state. Was a close alliance between the state and corporation in pursuit of the public good a historical anomaly, a particular innovation of the colonists?

MP:

Well, the corporation as a tool to advance the state’s interests had a long history before American colonization. But the likelihood that the chartered corporation would be the form through which the commonwealth of Massachusetts expressed its economic will was perhaps enhanced by the fact that Massachusetts was created as a chartered corporation by King Charles I in 1629. And the widely varied functions and purposes for corporations (though perhaps not youth soccer clubs) predated the colonization projects as well. The pre-modern state created corporations to promote a wide variety of public interests; international trading companies (the East India Company being perhaps the most famous), educational institutions (Harvard College was granted a corporate charter by Massachusetts in 1650), and civic corporations, designed to conduct the complex tasks of ruling urban spaces like the City of London, or, on a far smaller scale, the individual townships that made up the commonwealth of Massachusetts.

There was essentially no limit on the functions that a corporation could be created to perform—it could trade for spices, teach algebra, govern a colony, send missionaries to distant lands, or promote musical knowledge—so long as the state saw a public good that justified the creation of this privileged entity. Nor was there a uniform set of privileges that accompanied corporate status. The East India Company’s charter allowed it to raise its own army and navy to protect its interests. Not so for Harvard College. Ideally, the corporation would be granted powers and privileges appropriate for the public good it was meant to serve. At the time of Massachusetts’ independence, the corporation’s history offered many variants and many purposes, of which the “business” corporation was but one version.

By fighting an expensive war for independence, the individual states and the United States as a collective were left with a crushing burden of debt. The impoverished states had little spare fiscal power to promote economic development directly, through taxation and public spending. Therefore, the chartered corporation seemed like an ideal solution, a way to develop transportation infrastructure (turnpikes, bridges, canals) or to encourage manufacturing without spending non-existent state funds. If the public benefitted from a corporation’s activities, then granting the corporation certain privileges, such as a regulated monopoly on bridge tolls, seemed a small price to pay.

But the story the Handlins tell in Commonwealth is, like Hyde’s story in Common as Air, a tale of unintended consequences. The Handlins explain how the institution of the chartered corporation in Massachusetts was transformed between 1774 and 1860, under the pressure of the egalitarian forces of a democratic republic, and in the context of underlying conflict between commercial interests and the concept of the public good. The story is a complicated one, and Commonwealth often makes for difficult reading—it lacks the luminous clarity that Hyde, the poet, offers in Common as Air. But there are two key issues around which the Handlins’ story turns, and both of them are directly relevant to Hyde’s story as well.

First, limited liability. For many of the purposes that corporate entities were created to fulfill, individual members of corporations found themselves performing tasks that they would not have undertaken as private individuals. For example, when the Massachusetts towns conducted their business, the individual town officers, chosen by their fellow citizens, were not personally liable for damages. If a bridge that John Adams was charged to build within Braintree collapsed and a farmer lost a wagonload of hay, Adams would not pay for the loss. If there were damages to be paid, the town as a whole shouldered the blame. Without such protection, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to convince private individuals to take up the burden of serving the corporate body politic. For obvious reasons, this privilege also spilled over to the participants in business corporations chartered to perform a public good. If the same farmer’s horse went lame crossing a bridge built between two towns by a chartered corporation, then the corporation as a whole, not the individual directors, investors, or employees, shared the blame—individual liability for acts of the corporate body was limited in the corporate charter.

The question grew more complex when considering the extent of the financial liability of the members to the corporation. For the civic corporation of the town, there was ultimately no limit on the town’s ability to assess its citizens to pay the town’s debts. If a town, that is, a citizens’ corporate collective, decided to build bridges, and if the ultimate cost of the bridges turned out to be twice what the town expected, the citizens could be assessed as much as necessary to pay the extra costs—there was nowhere else to turn, after all. Ideally, this collective financial liability of the body as a whole provided a check on what the townspeople as a corporate entity would take on (and, in its nightmare worst-case-scenario, this speaks to the situation that countries like Iceland, and the various members of the European Union, have been facing in the past few years).

But what about a business corporation? If a bridge cost twice as much to build as expected, who was liable for the corporation’s debts? Could a bridge corporation assess (or tax) its members or investors to an unlimited degree in order to pay off its debts, the way that towns could? The Handlins describe a series of decisions from the early nineteenth century in which the Massachusetts courts said, essentially, no. Although investors were, like townspeople, members of a corporate body, their liability for its obligations was limited. Why? Because without this added privilege of limited liability, it would prove impossible for corporations to gain investors and share the risks, to raise the funds necessary to carry out their tasks. In that case, the public purposes sought by the state in chartering the corporation would go unfulfilled.

RCM:

It is striking that a public purpose still guided rule-making at this point for business corporations. As you mentioned earlier, the modern U.S. business corporation provokes so much anxiety in a place like Ecuador because it seems to have enormous privileges but no responsibilities save returning profits to investors. How were corporations able to so simplify their objectives and divest themselves of civic duties?

MP:

The limited liability decisions proved to be the beginning of a separation between the civic corporation and the business corporation. The purpose of this distinction still appeared to be the promotion of the public good, to facilitate the commonwealth’s desire that business corporations would have the tools they needed to take on large and useful projects. But with this subtle change, the law of the commonwealth elevated the individual financial interests of investors in the business corporation, giving them an importance comparable to the public good in a way that was very different from the civic corporation.

The second critical change in the nature of corporations also seemed to stem from the desire to promote the public good. This was the rise of general incorporation laws, a process in which the monopoly privileges of chartered business corporations were gradually undermined. In the old monarchical regime, privilege was not a problem. That world was hierarchical, and all persons were decidedly not equal before the law. The crown had the power to reward those who performed notable public services for the kingdom with special honors and privileges. But in the newly formed American republics, privilege was a problem, and the privileged status of the traditional chartered corporation, a child of the old order, would inevitably be challenged in the new. Here, the famous Charles River Bridge case, ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1837, offers the clearest example of this transformation.

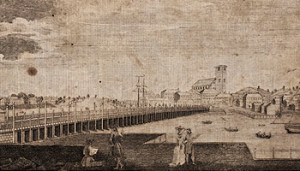

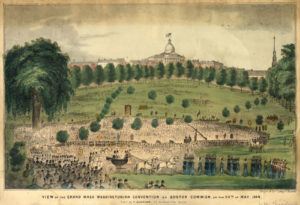

For many decades in the colonial period, the Massachusetts General Court had authorized a ferry to carry passengers back and forth across the narrow stretch of the Charles River separating Boston from Charlestown. The proceeds from this ferry had gone to Harvard College as part of the state’s support for that chartered corporate body’s promotion of learning and knowledge. But in the postwar recovery of the 1780s, as the two neighboring cities rebuilt from the war’s destruction, it was clear that a ferry could no longer handle the growing volume of traffic. The General Court chartered the Charles River Bridge Company (CRB) in 1785, offering its directors and investors a special set of privileges in return for building this useful public amenity. On condition that it continue payments to Harvard College for the lost ferry revenue, the corporation was entitled to keep all the profits from the bridge tolls for a period of forty years, after which ownership of the bridge would be turned over to the Commonwealth as public property, and bridge travel would be free and open to all. In fact, these provisions made the CRB charter granted by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts extraordinarily similar to the terms of early patent law created by the U.S. Congress—a temporary monopoly on the proceeds of the “invention,” followed eventually by permanent public benefit, Hyde’s Republican Two-Step in a nutshell (fig. 3).

Several years later, the General Court awarded a charter to a similar bridge company, farther up the river, connecting Boston to Cambridge. When the CRB proprietors complained that this new bridge would cut into their accustomed revenues, the state responded by extending the CRB’s entitlement to the profits, from 40 years to 70 years, well beyond the likely lifespan of the original proprietors. In the meantime, the CRB proved to be a wild success. A share of stock in the bridge, valued at $333 when issued in 1785, had risen to over $2000 by the 1820s. In the company’s growing desire to protect its investors’ profits (and to defer the public its free travel), we see the practical consequences of the limited liability cases and their elevation of investor interests at the expense of the public good, an exact parallel to the way Congress in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has granted repeated extensions of the length of copyright and patent benefits to their owners.

It was precisely in response to this affront to the good of the commonwealth that the privileges of the CRB were challenged. In 1823, a competing group of investors petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to allow them to build a bridge immediately adjacent to the Charles River Bridge. Eventually, the legislature granted this group, the Warren Bridge Company, a charter which mandated that they turn their bridge over to the public within six years, as soon as the tolls, which were to be fixed at the same rate as the Charles River Bridge tolls, had paid for the costs of construction, plus five percent interest to the investors, (compared with the 600% return that the CRB had already yielded to its shareholders over forty years). A brand new and soon to be free bridge, immediately adjacent to the older toll bridge, would (and eventually did) undercut the CRB and its storied profits, so the CRB sued the state for breach of contract. Although its charter did not say as much, the CRB claimed that monopoly control over the route from Boston to Charlestown was an implicit right in their charter, and that to promote the building of an adjacent bridge therefore violated the privileges to which the CRB investors were still entitled for decades to come.

After a long and complex legal fight, the U.S. Supreme Court finally decided the case against the CRB. In writing the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roger Taney overruled the sanctity of property and contract arguments, the so-called “vested property rights,” of the CRB, and instead based the decision on yet another definition of the public good. Not only did the CRB’s monopolistic and, for all practical purposes, perpetual control over a popular travel route clearly undercut a vital public interest, preventing potentially better, safer, or faster means of travel from developing, but the very fact of privileging one group, the CRB proprietors, at the expense of all other entrepreneurial citizens who might perform the task equally well, meant that the state was effectively creating a commercial aristocracy, a corporate person possessing rights and privileges denied to all others. The Charles River Bridge case thus paved the way for general incorporation laws, where the corporate form—including the limited liability privileges established in earlier decisions—became available to any business group that wanted to use it.

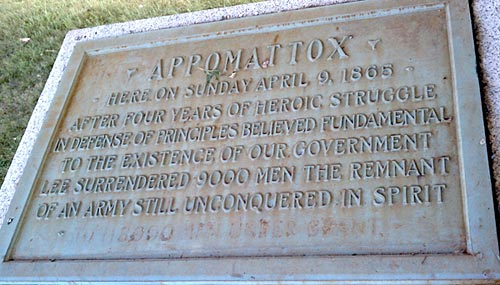

With Taney’s decision and the subsequent rise of general incorporations laws, the original logic behind the monarchical state’s creation of corporate personhood melted away in the face of demands for equal treatment of all “persons” in republican society. What remained from the corporation’s original purpose was a set of privileges, whose purpose now was nothing more than to advance and protect the business interests of entrepreneurs and their investors. By the end of the Handlins’ story in 1860, the second step of the Republican Two-Step, the corporation’s responsibility to serve a well-defined public interest, has vanished completely.

So now we see more of the story of how we got where we are today. Two intertwined legal institutions, corporations and intellectual property rights, both founded in a monarchical world of privilege, both adopted as temporary and limited privileges to promote the general public good, have each evolved in ways that have diminished the duty to the public, while retaining and expanding on the privileges. We might see these changes as simply the result of greed, the desire among individuals or corporations to see their property and privileges as nothing but commodities, forgetting the role of the state in their initial creation. But at the same time, we can see the changes as natural outcomes in a democratic and egalitarian society, especially with regard to corporations, where the idea of granting privileges to some at the permanent expense of others, as in the Charles River Bridge case, seems anathema to the freedom and opportunity we wish to foster.

RCM AND MP:

Where does this leave the Andean demonstrators in the face of U.S.-Ecuador trade agreements? Where does it leave us all, in the face of Google and its 17,000 new patents? Might an answer lie in carrying forward the logic of Common as Air and rethinking the Republican Two-Step?

For all those who no longer believe in the ability of the state, the citizens’ collective, to identify a public good beyond the interests of any given person, i.e. for “libertarians” (in U.S. terminology) or “liberals” (as the rest of the world uses the term) who see nothing but the market’s invisible hand as the only justifiable good, we ask this: if you can see no coherent way for the state to identify and enforce Step Two—service to the public – then why should the state continue to grant Step One—special privileges to “persons” of any kind? The Constitution gives Congress the power to promote science and useful arts through patent and copyright protection, but Congress does not have to exercise that power, which is a vestige of a monarchical world, and can change the terms of those protections. State law creates the privileges that corporations often use in ways that cause demonstrable harm, but state laws can change these institutions as well. However, we suspect that those who clamor for “free markets” do not actually have the courage of their convictions necessary to give up the privileges. Having lost sight of the civic responsibilities of the Republican Two-Step, they have become equally blind to the service that the state now offers them in the extension of copyrights and corporate liability protection. At times it takes the black smoke of a street protest to remind us just how hardened and lopsided government-backed privileges have become in the United States.

For all those who continue to believe in the commonwealth ideal, that our government can identify measures of public well-being beyond the private interests of individuals (the camp in which we place ourselves), we urge that an active case be made to promote a better understanding of this history in the effort to restore Step Two of the Republican Two-Step. Yes, the privileges of corporations, copyright, and patent may be vestiges of an abandoned monarchical world. But they are also deeply entrenched in our world, probably impossible to eradicate entirely. Our only alternative is to fight for what makes the privileges of corporation and copyright worth preserving. We can once again extend the state’s power, our collective power as citizens, to insist that private property and public responsibility be inextricably linked, and that privilege always be made to benefit the public, and we can create ways to equalize the power of those, like Andean Indians, overwhelmed by the limitless privileges of others. Otherwise, we as citizens of the republic, who created these privileges through our constitutions and laws for the sake of the public good, will stand impotent in the face of the monsters these creations have become.

This article originally appeared in issue 12.1 (October, 2011).

Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld teaches anthropology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He is the author of The Native Leisure Class: Consumption and Cultural Creativity in the Andes (1999); Fighting Like a Community: Andean Civil Society in an Age of Indian Uprisings (2009); and, with Jason Astorio, “Economic Clusters or Cultural Commons? The Limits of Competition-Driven Development in the Ecuadorian Andes,” Latin American Research Review (2009).

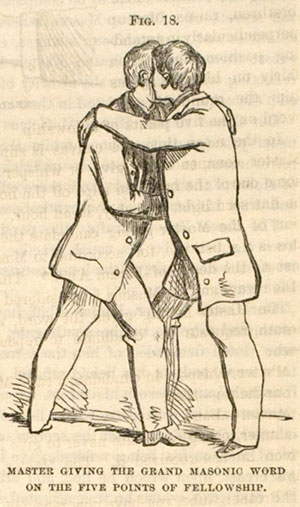

!["Master Giving the Grand Masonic Word on the Five Points of Fellowship." From Malcolm C. Duncan, Duncan's Masonic Ritual and Monitor: or Guide To The Three Symbolic Degrees of the Ancient York Rite . . . ," 3rd ed. (New York, [1866?]). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.](http://commonplacenew.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/8.2.Bonica.1-178x300.jpg)