Having been involved in different levels of reenacting for 30 years, from the French and Indian War to the Western fur trade era, my concern for greater authenticity has grown. In my early days of entertaining with an old time band at pre-1840 rendezvous, we never questioned our music, being a mixture of popular songs of string bands from the 1930s and fiddle tunes from anywhere. When the band dissolved and my interest deepened, I began to notice the absence of period music at these historical events. Here were some of the most dedicated proponents of period accuracy in everything from clothing to accouterments, yet not the music. To be sure, there were some trained musicians playing period violin compositions from the sheet music of the day, a necessary component of period accuracy. But my focus has been on vernacular tunes played by untrained fiddlers who had an intuitive knowledge of their tunes and traditions. So for the past 10 years I have studied, recorded, and performed archaic fiddle styles of early American fiddlers from the upper South. These were among the tunes that accompanied westward expansion.

One challenge to this approach is choosing which fiddle to use to recreate tunes of earlier time periods. All fiddles before the early 1900s had gut strings. Fiddles before the American Revolution were baroque instruments; fiddles from that time up to the Civil War were more modern looking, yet still had a shorter neck. In my days with the band, I had only one fiddle and didn’t know the history. Today I must limit the number of fiddles I take to a performance and trade some period accuracy for an archaic feel.

A further hurdle is the choice of tunes. Many are easily traced back to the Civil War. But for my time periods before 1840, I consult several printed sources. Knauff’s Virginia Reels, published in 1839, is a series of forty fiddle tunes collected in eastern Virginia and arranged for pianoforte.Then from the Cumberland Gap of western Virginia comes the Hamblen Collection of fiddle tunes from the early 1800s as played by David R. Hamblen (1809-1893) and son Williamson (1848-1920), arranged and copied by grandson A. Porter (1875-1958). Of the 700 tunes said to have been known by David R., only twenty-two are transcribed, along with fifteen from Williamson. I also seek recorded sources from the Library of Congress and other field recordings whose subject matter and style suggest an early provenance.

We will never know exactly how the fiddling forefathers sounded. But by listening to extant recordings of senior source fiddlers who can trace their tunes and playing styles back to a time before radio, before the minstrel stage, before modern notions of pitch, timing, and tonality, we can get significant clues to the sounds of those early fiddlers. For example, Emmett Lundy, a North Carolina fiddler born in 1864, was recorded for the Library of Congress in 1941. He learned many of his tunes from Green Leonard, born in 1810. He is but one of many from whom we get a concept of early playing styles. As re-mastering techniques improve, more old recordings are released for those on the quest for the sounds and tunes of those early fiddlers.

Visit Christian Wig’s website.

Sound files:

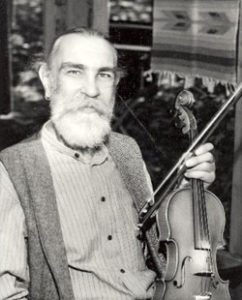

“Gaston,” Christian Wig, fiddle, Whitt Mead, banjo. Track from Chadwell’s Station (2008). Courtesy of Christian Wig Ensembles.

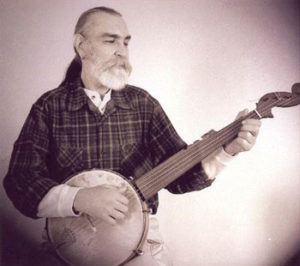

“Pompey Ran Away,” Christian Wig, banjo. Track from Chadwell’s Station (2008). Courtesy of Christian Wig Ensembles.

“Betty Baker,” Christian Wig, fiddle, Mark Ward, banjo. Track from Come Back Boys & Feed the Horses (2011). Courtesy of Christian Wig Ensembles.

“Cluck Old Hen,” Christian Wig, banjo. Track from Come Back Boys & Feed the Horses (2011). Courtesy of Christian Wig Ensembles.

“Pride of America,” Christian Wig, fiddle. Track from Chadwell’s Station (2008). Courtesy of Christian Wig Ensembles.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).