On July 13, 1863, a riot in New York City that had begun as opposition to the draft for the Union’s Civil War army morphed into a violent mob that targeted African Americans. That afternoon a large crowd attacked the Colored Orphan Asylum, looting it and then burning the building to the ground. This attack has been a focal point of discussions about the New York draft riots since the first newspaper accounts of the riots began appearing, but one element in the contemporary accounts stands out to me as a historian of childhood, an element that has generally escaped notice in the frequent recitations of this story: not only did all 233 African American children who lived in the institution escape unharmed, but according to some accounts they were allowed to “proceed unmolested” to safety through an otherwise riotous and bloodthirsty mob. A description of the children processing safely through the violent crowd appears in every version of the story recorded by the managers of the institution itself, with some of the most evocative language penned in an 1868 annual report, in which they wrote,

the long line of trembling, terrified little children filed quietly down stairs and through the halls into the very body of the mob, who literally filled the enclosure, and whose savage yells and inhuman threats thrilled like a death note on every heart . . . The human mass swayed back as though impelled by an unseen power—not a hand was raised to molest them, and without sustaining the slightest injury, children and care-takers reached the station house.

Surely the managers intended the “unseen power” here to refer to God, but there are other possible explanations for the behavior of the mob that managers recounted. One of these, I want to suggest, was New Yorkers’ own beliefs about childhood and the protections it afforded.

Age studies scholarship encourages us to interrogate understandings of age and stages of life as social constructs. As with other social constructs, scholars argue that things that seemed natural, inherent, and biological to members of that society were in fact—at least partially—constructed by the society of which they were a part. Beliefs about the traits, needs, and rights of people based on their age have therefore varied by time and place and so historians are well-placed to interrogate them. Scholars have worked to uncover how Americans in different time periods conceived of children and childhood, and a growing body of literature captures antebellum Americans’ emergent belief that children were naturally and rightly innocent, malleable, and dependent. These were the assumptions that drove the creation and operation of orphan asylums during this period, replacing indenture for young children with institutionalized care and education as labor increasingly came to be seen as outside the appropriate purview of childhood.

The Colored Orphan Asylum was one of many such orphan asylums in mid-nineteenth-century New York City, one which served African American children who had lost at least one parent. This begs the question: does the creation of this institution along lines similar to those of other orphan asylums suggest that race was irrelevant to nineteenth-century understandings of childhood? It is important to note that the question here is not whether nineteenth-century white New Yorkers saw African American and white children as equals. The evidence overwhelmingly indicates that most did not. The question rather is whether white New Yorkers’ beliefs about the traits, needs, and rights inherent to children of a specific age extended to both black and white children in the designated age range. In other words, how universally did nineteenth-century Americans apply their professed ideas and assumptions about childhood? Examining the history of the Colored Orphan Asylum, and in particular looking at the episode of the destruction of this institution during the draft riots, suggests that in many respects white New Yorkers did apply their understanding of age-related traits to children regardless of race but that this did not always lead to the protection and treatment generally understood in the period as the proper purview of children. In nineteenth-century New York, African American children were regularly discussed as possessing the malleability, dependence, and helplessness attributed to children of all races, but despite this, these children were often placed in vulnerable situations. While there was significant variation in the ways white New Yorkers treated African American children—with the white women who founded the Colored Orphan Asylum and the white mob that destroyed it exemplifying the spectrum—as a whole white New Yorkers conceived of African American children as children, but their assumptions about the traits and needs inherent to age existed alongside their beliefs about race. Neither the children’s race nor their age trumped the other, but rather existed simultaneously in the minds of white New Yorkers.

That the children escaped the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum unharmed is agreed upon by every contemporary account of the event, even as the authors of these accounts disagreed about everything from the number of children (ranging from 200 to 1,000), whether or not the adults in the asylum had warning, and the method of the children’s escape. In addition to the assertion quoted above that the children walked through the crowd unharmed, some contemporary versions of the story claim the adults of the asylum snuck the children out a back door or that the children were saved from a violent demise by the actions of a heroic Irishman. And while the definitive means of their escape cannot be proven, it is no less fanciful to believe that a mob parted to allow the children to walk through untouched than to believe that 233 children—the number confirmed by institutional records—snuck out of the building without being noticed or that one individual was able to singlehandedly restrain a violent mob. Furthermore, upon closer examination, affording the children such an escape would actually be in keeping with other actions of white New Yorkers toward the children living at the Colored Orphan Asylum in the nineteenth century. In protecting the children’s bodies on July 13, 1863, even while terrorizing them and destroying their home, the mob repeated a pattern in which nineteenth-century white New Yorkers recognized, articulated, and to some extent supported African American children’s status as children but denied them the full protections and rights such status extended to white children.

New York City draft riots

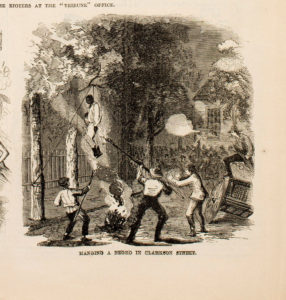

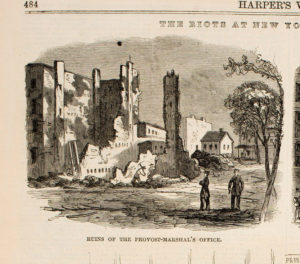

The New York draft riots consumed New York City July 13-17, 1863, when a mob erupted over fears and frustrations about the initiation of a draft for a bloody war that was increasingly touted as a conflict to end slavery, their own precarious economic status, and their place relative to African Americans within the city. In the course of this riot over $1.5 million of property (at least $30 million in today’s dollars) was destroyed and more than 100 people—mostly African American men—were killed. Thousands more were injured, and the terror inflicted on the black community led to an exodus out of the city.

Scholars and contemporary accounts of the riots agree that after initially focusing on governmental, military, or elite targets, the mob then turned its sights on the Colored Orphan Asylum, a charitable institution that housed and educated orphaned African American children and was supported by a combination of donations and city funds. The building was looted and then burned, with complete physical destruction but—as established earlier—no loss of human life. This took place in the midst of a riot in which African Americans were targeted for violence. On a day in which the New York Times noted that the crowd spent a lot of the day “amusing themselves” by “chasing and beating every person of color who chanced to make his appearance” and when “It seemed to be an understood thing throughout the City that the negroes should be attacked wherever found, whether then [sic] offered any provocation or not,” it is noteworthy that none of the African American children from the Colored Orphan Asylum were harmed. That in the chaos and violence of the riots all 233 children, some of whom became separated from the group and were navigating the city on their own, were protected by adults and spared by the mob suggests that despite the attack on their home, the children did enjoy something of protected status.

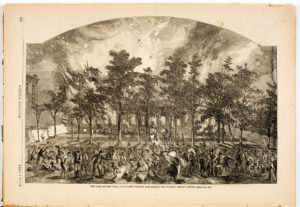

Contemporaries certainly believed these children were entitled to such protected status. In the midst of days of violence and destruction, the attack on an orphan asylum—a monument to the traits of dependence and helplessness associated with childhood—provoked outrage in contemporaries, suggesting a widespread application of the rights of childhood to the African American children of the Colored Orphan Asylum. Newspaper accounts of the riots published throughout the country frequently emphasized the burning of the asylum as one of the worst offenses of the riots. Harper’s Weekly’s visual depiction of the burning of the asylum was the largest of their eleven images of the riots contained in the August 1, 1863, issue, filling an entire page of the three-page spread, leaving the other ten images to share the remaining two pages. This emphasis was paralleled in the text, which exclaimed, “The burning of an orphan asylum is infamous beyond parallel in the annals of mobs.” Given the notorious violence of many mob actions, and contemporary accounts’ gruesome depictions of the violence perpetrated on African American men by this very mob, Harper’s Weekly’s insistence that the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum was particularly heinous seems to rest on the assumption that children—and orphaned children in particular—were a separate and protected class. Many contemporaries, then, seemed to agree that all children—regardless of race—deserved special protection and that even among the many horrible actions of a mob, burning an orphan asylum was a particular low.

The juxtaposition between the perceived proper treatment of the children and their abuse at the hands of the mob was captured by a New York Times account four days after the attack on the asylum, which credited the escape of twenty of the children separated from the rest to interference by some in the crowd. It exclaimed, “It hardly seems credible, yet it is nevertheless true, that there were dozens of men, or rather fiends, among the crowd who gathered around the poor children and cried out, ‘murder the d — d monkeys,’ ‘Wring the necks of the d — d Lincolnites,’ &c. Had it not been for the courageous conduct of the parties mentioned, there is little doubt that many, and perhaps all of those helpless children, would have been murdered in cold blood.” The author of this piece expressed a belief in the universal applicability of the traits and protections of childhood and assumed his readers would agree that anyone who did not extend such characterizations and protections to all children was a “fiend” rather than a man.

The New York Times piece—and the version of the children’s escape it recounted—juxtaposed two groups of white New Yorkers—those who upheld the children’s status as children and those who denied it. In other accounts of the children’s escape, however, the two ideas were described as co-existing even within the mob itself. The accounts of the event penned by those running the institution each relate in quick succession the vicious violation of the rights of childhood represented by the destruction of the asylum and the simultaneous protected status of the children represented by their escape. In multiple accounts from the year immediately following the riot, the managers depicted the mob as unrestrained, threatening, and insensitive to the children’s protected status, but simultaneously noted that the children were “permitted” to escape “unmolested.” Managers initially offered no theories for this disjuncture, but in later accounts managers attributed the children’s escape to God’s intervention and, in one case, the mob’s own recognition of the rights due to the children as children. In a dramatic recounting of the event three decades after it occurred, in the institution’s 1896 annual report, managers described a mob “thirsting for their [the children’s] very lives,” who ransacked the house and “heap[ed] horrible abuse upon the helpless inmates.” Then, however, as the children processed out the door and into the mob, “the sight of a helplessness so absolute stirred in the hearts of the rioters a feeling akin to pity, cursing was turned to blessing. And then a hush fell over the crowd, the seething mass fell back upon itself, and a passage was opened for the children.” In this later account the children’s escape and the mob’s mercy were explicitly attributed to the orphans’ status as helpless and defenseless children, a fact recognized even by the least likely group of white New Yorkers.

Analyzing this event from the perspective of age studies suggests that African American children occupied something of a liminal status in white New Yorkers’ perceptions of them as children. The asylum residents’ status as orphaned children protected their bodies but not their home during the riots. The burning of the institution provoked national outrage and led to an influx of donations, but the asylum was not able to rebuild on its previous site and there was no consideration—at least that I have seen—of admitting these children who had lost their home into those institutions serving white children. It is also clear that while the children were safe and many adults worked to ensure this, they were not spared from taunts, threats, and physical intimidation during the riots, even after escaping to the station house. That these African American children naturally possessed the dependence and helplessness assumed to belong to children was not challenged during this episode, but while this prevented their physical harm, it did not insulate them from the racism and violence of the riots.

Institutions for children

The children’s escape through the mob is evocative, but it was clearly an atypical event and the mob cannot be taken as representative of white New Yorkers as a whole. When the status of the Colored Orphan Asylum and its residents are considered more broadly from the angle of perceptions of childhood, however, it becomes clear that the characterization of these children as existing in a liminal space regarding understandings of childhood was not limited to this one, clearly unusual, event, but rather part of a larger pattern regarding white New Yorkers’ conceptions of the rights, traits, and proper treatment of the children who came into the care of the Colored Orphan Asylum. As was seen during the riots itself, white New Yorkers were not a homogenous group but, taken as a whole, policies regarding African American children in nineteenth-century New York City suggest a widespread belief that these children possessed the traits of childhood and yet were not entitled to the full range of protections afforded to white children based on their age.

The perception that African American children both possessed the traits believed to be inherent to children and yet were not entitled to the same protected childhood as white children is apparent in the very founding of the Colored Orphan Asylum itself. The institution was founded in 1836 by a group of Quaker women who were disturbed by the fact that African American children who ended up in the city’s care were housed, not with other children in the institutions for children on Long Island Farms (or later Randall’s Island), but rather “retained with the adults in the crowded buildings at Bellevue” and “in care of a half-deranged man.” These women believed the city was not treating African American children in accordance with the rights and needs of childhood, rights and needs these founding women believed the children inherently possessed due to their age. Given that Long Island Farms housed white children who were poor and primarily the children of immigrants, it is clear that race rather than class or family background was the distinguishing factor between those children who were admitted and those who were excluded from the city’s institutions.

Throughout their annual reports, pleas for funds, and public presentation of their charges, managers consistently emphasized the residents’ status as children and highlighted the malleability, dependence, and helplessness commonly discussed in nineteenth-century culture as inherent traits of childhood. Managers of the Colored Orphan Asylum explained in their first annual report, which served as both justification for the institution’s founding and plea for financial support, “When it is remembered that three asylums for white children are liberally supported in this city and that there still remained a class excluded from a share in their benefits, with souls to be saved, minds to be improved, and characters to be trained to virtue and usefulness, can any for a moment doubt the necessity for establishing such an institution.” The managers’ emphasis on the potential for training that all children were presumed to possess suggests that they assumed African American children possessed the same malleability or plasticity that was emphasized as an inherent trait of childhood more broadly in the period. The assumed malleability of childhood made it essential that children be placed in environments designed to educate them and shape their character. Managers similarly emphasized the children’s dependence at every turn, consistently evoking the children’s status as orphans and complete reliance on the aid of the institution and its benefactors. In these ways they highlighted the traits associated in nineteenth-century New York with childhood, seeking aid for their institution on the grounds that African American children’s status as children entitled them to the years of provision, education, and nurturing the institution aimed to provide, elements recognized in the period as inherent rights of childhood.

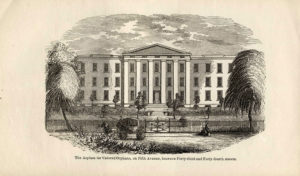

City leaders did not refute the Colored Orphan Asylum managers’ claims and in fact helped fund the institution and publicly endorsed the work the Colored Orphan Asylum did, but they were unwilling to take action themselves, exemplifying the uneven treatment of African American children in nineteenth-century New York City. The Commissioner of the Almshouse, for example, wrote in his 1849 annual report that the institution “cannot fall short of eliciting the unqualified approval of every friend to human sympathy.” While the city was unwilling to integrate the children’s branch of the almshouse to include African American children or to create a separate child-care facility for these children itself, it was supportive of the work the managers of the Colored Orphan Asylum did to serve the children in their own institution. In other words, while city leaders accepted African American children’s status as children, they were unwilling to do the work required to ensure that these children were the recipients of the care they articulated as appropriate for other children. Similarly, at a Board of Aldermen meeting held two weeks after the asylum was destroyed, Alderman Ottiwell moved for the city to allot $50,000 toward the reconstruction of the Colored Orphan Asylum by specifically evoking the dependence and innocence associated in nineteenth-century America with childhood. He argued that the burning of the asylum made the children dependent on the city, “a trust which, from the helplessness and utter destitution of these unfortunates thus suddenly deprived of shelter, food and raiment, should be at once accepted.” Their “total dependence” and the “undeserved, yet bitter and unrelenting persecution” they had experienced, he continued, entitled them to “the sympathies and commiseration” of the city as well as “of all right minded and enlightened men.” The city did eventually compensate the association $70,000—part of $1.5 million it paid in damage claims from the riot—although it prevented the institution from rebuilding on its prime location on Fifth Avenue between 43rd and 44th Streets, pushing it to relocate farther up the island. City officials did not dispute—and at times articulated—the age-related needs and claims of African American children, but did not prioritize these claims, privileging the needs of white children and other financial concerns.

African American children’s liminal or provisional classification as children is also apparent in the city’s bifurcated approach to the question of whether to classify African American children as children within their own increasingly age-stratified institutional systems. While African American children were not permitted in the children’s branch of the Almshouse (Long Island Farms and Randall’s Island) through at least the 1870s, they were admitted during these years to the city’s institutions for children who had committed crimes or were believed to have delinquent tendencies (the House of Refuge and the Juvenile Asylum). In housing African American children in these institutions for delinquent children, city leaders revealed their assumption that children of all races were inherently malleable and so needed to be housed apart from adult criminals to foster rehabilitation. However, in only including African American children with white children in those city-run institutions that housed delinquent children rather than those admitted without such a designation, they categorized African American children as not entitled to the full protections of childhood offered to white children. City leaders did not explain their reasons for different policies regarding racial integration at the city institutions serving children, but one characteristic frequently attributed to children in this period that may have been a factor is the presumption of innocence. Children in delinquency institutions were presumed to be lacking this supposedly natural sense of childhood innocence (akin to what we might call naiveté). In addition to those children admitted as a consequence for committing a crime, many children found themselves in these institutions due to a label of being “incorrigible” or a presumed corruption due to time on the streets or in other environments thought corrosive to childhood innocence. Leaders did not articulate a connection between this loss of innocence and race, but as that was a major factor differentiating white children in the two institutions, this may be one characteristic of childhood that city officials did not assume occurred evenly across racial lines.

City policy and the actions of the mob that looted and burned the Colored Orphan Asylum do not align neatly or offer a consistent pattern, but they do reveal that white New Yorkers recognized African American children as possessing many of the traits and rights of white children due to their age, but that this fact did not serve to ensure the children’s protection or public support. Looking at this well-known event through the lens of age studies adds a layer of nuance to our discussion. Age studies asks us to consider the way a society’s understandings and assumptions about age and stages of life affected life for people within that society. An examination of the treatment of children who lived at the Colored Orphan Asylum in nineteenth-century New York City reminds us that the interplay between age and race (or other facets of identity) is complex. Not only have conceptions of age and the traits believed inherent to various stages of life varied by time and place, but even within a given time and place they have often not been evenly applied to all people of a designated age. This presents challenges for an academic working to uncover and articulate boundaries or definitions for age-related stages of life, but while they were not always consistent, historical actors’ understandings of age and its related traits and needs had real, tangible effects on the treatment and lived experience of children. In the case of the children living at the Colored Orphan Asylum on July 13, 1863, these ideas about age just may have saved their lives.

Further reading:

Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans Manuscript Collection at the New-York Historical Society. Many of these records have been digitized and are freely accessible online.

T[homas] H[enry] Barnes, “My Experience as an Inmate of the Colored Orphan Asylum.” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago, 2003).

William Seraile, Angels of Mercy: White Women and the History of New York’s Colored Orphan Asylum (New York, 2011).

Barnet Schecter, The Devil’s Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America (New York, 2005)

This article originally appeared in issue 17.2 (Winter, 2017).

Sarah Mulhall Adelman is an assistant professor of history at Framingham State University. She has published on the political culture of American Catholic women religious and is currently working on a project about nineteenth-century orphan asylums and conceptions of childhood.