I would have liked to open my “foodie” essay about pigeon with a description of cooking and sampling in my own kitchen one of the migratory birds that John James Audubon considered so tender. But I am more than a hundred years too late to do this for the generation of pigeons that I’m thinking about. Had I access to fresh pigeon in the market—say Boston’s Quincy Market in 1820 shortly after it had opened—along with my interest in testing preparations of this popular game bird, I would be sharing an account of the results with readers. That is what the cookbook authors Mrs. N. K. M Lee (calling herself a “Boston housekeeper”) and Lydia Maria Child were both able to do circa 1830 when pigeon was plentiful in the markets. We know that this was the case through commentators such as Audubon and Christopher C. Baldwin, whose descriptions of the flight patterns and hunting customs of birds such as the passenger pigeon take their place in the human food supply for granted.

My interest in Audubon and Baldwin has recently been piqued by a couple of books that I’m editing for publication to mark the bicentennial of the American Antiquarian Society: The diary of Christopher Columbus Baldwin (a 2010 collaboration with Jack Larkin published as A Place in My Chronicle) and the Society’s bicentennial history, authored by Philip F. Gura, to be published in 2012. By now, you might be wondering what in the world they have to do with pigeons.

Audubon, it turns out, visited Antiquarian Hall in 1840 during a tour of New England to line up subscribers to the octavo edition of Birds of America, which appeared in seven volumes during that decade. (He did not make a sale at AAS, although the Society subsequently acquired a set connected to that visit.) The packages of reproductions of his paintings were the bookends for a text, Ornithological Biography, in which he and his co-author, William MacGillivray, described the birds that he had illustrated. The commentary drew upon notes that the artist had made along the way. Thanks to the University of Pittsburgh’s digital edition, one can search for such words as “tender,” “tasty,” and “juicy” as well as “market” for a view of these volumes as a guide to edible wild birds (at least in Audubon’s opinion).

Baldwin, who became the Society’s first full-time librarian, serving from 1832 to 1835, kept an extensive diary in which he documented his activities. As effective as he was at the indoor pursuits of a librarian, he was also an outdoorsman who knew how to handle a gun and who numbered hunters among the friends of his youth. Asa Hosmer of Templeton, Massachusetts, was one of them. Baldwin described Hosmer as “a hunter by profession having done nothing else for several years.” Quoting, as was often his custom, from a conversation, Baldwin wrote: “He informs me that during the last fall he caught hundred and thirty dozens of pigeons, and the story is confirmed by his father.” In July 1830, Baldwin spent two days hunting pigeons and again in September. He was not particularly successful, writing in July, “The woods are thick with them, but they are in the tops of trees and so beyond the reach of shot.” The first day he went hunting in September he had similar luck. “Hunt pigeons, and fire at many and kill very few,” but two days later, when he returned to the hunt and was successful, he was “reprimanded” by a neighbor “for killing what he calls his pigeons.” Baldwin disagreed: “They are on my father’s land and far from his bed.” The next summer, when Baldwin returned home to Templeton, his relaxation included hunting, but with a different weapon “procured … for hunting pigeons and it answered a good purpose.” He wrote that he had “purchased me an old gun of that class called Queen Ann’s, carrying ten balls to the pound, and [had] it new stocked, with a good lock, for which I paid six dollars.” He was satisfied with the five pigeons he killed in September during a day in the out of doors.

Baldwin’s hunting was recreational, but the neighbor, George W. Bryant, who had scolded him earlier, was like Hosmer in the business of marketing pigeons, and Baldwin was evidently intrigued. He was so interested in this enterprise that he gathered some information about Hosmer and pigeons and then wrote one of his own extended reflections that appear from time to time in his chronicle.

Asa Hosmer, Jr., is a hunter by profession. He does nothing but hunt, and has made it his whole business for above ten years, and what is remarkable, he gets a good living by it. He told me that last year he caught over eight hundred dozens of pigeons in Templeton, and that this was not one-half the number taken in the town. Mr. Joseph Robbins and a person by the name of Parks, in Winchendon, caught thirteen hundred dozens; and a Mr. Harris of that town about seven hundred doz. more. They have taken nearly the same number for several years past. They find a market for them in Boston, Worcester, Providence & their vicinity. They [pigeons] sell from one dollar and fifty cents to two dollars per dozen, and the feathers sell for enough more to pay all expenses.

Pigeons—like some other breeds of birds—were easy to hunt, indeed, so easy that the hunt couldn’t be sustainable. “Innumerable thousands of pigeons have been seen during the fore part of this month of this year in various parts of New England,” Baldwin continued. This was the scary part: it was frightening to see the sky blackened by a mile-long flight of birds, “an appearance which, with our ancestors, would have created the most alarming apprehensions.”

It is said that their flight portends bloody war. I can well remember that in the spring of 1811 a flock passed over Templeton that was many hours in sight, and so large as to cover the whole horizon. They first appeared about half an hour before sunrise and continued until after ten o’clock. They were going to the north-east. All the old people said it was a sign of war; and, whether the pigeons had anything to do with the affairs of men or not, I cannot tell, but this is nevertheless true, that the United States did declare war against England within fourteen months from that time.

Baldwin’s reflections continued with descriptions of other sightings that were followed by transformative moments in American history, in 1774, and preceding Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia, in 1575 and 1576.

Audubon’s descriptions of the “astonishing numbers of pigeons in our woods” jibe with Baldwin’s but cover a more expansive geography—from New York State to Pennsylvania to Louisiana. “In 1805 I saw schooners loaded in bulk with pigeons caught up the Hudson River coming to the wharf at New York, where they sold for one cent apiece,” he wrote. Twenty-five years later, in March 1830, Audubon reported that pigeons were “so abundant in the markets of New York that piles of them met the eye in every direction.” Despite the “immense numbers” killed and the “cruelty in pursuing them,” he reported that “no apparent diminution ensues.” Some were caught in nets, others were killed when the flocks stopped to drink at a water source. Such complacency about the damage inflicted on the large, migrating flocks would eventually have dire results for the pigeon population, but for now, what mattered most was that the markets were supplied.

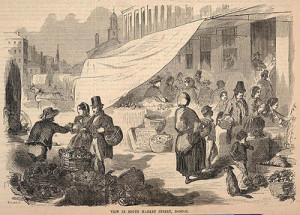

With the food markets so reliably and well stocked seasonably with pigeon, it is surprising that the record of how the birds were transported thence is so opaque. Details about relationships between farmers who remained in rural New England with peers who had established themselves as vendors at Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market have been teased out in relation to other country products, so it seems plausible that the shooters may have relied on a particular vendor in Boston. Or it is possible that they might have avoided a middleman. Winslow Homer’s drawing of a “View in South Market Street” (fig. 3) offers a visual suggestion. On the left is a farm wagon and in the foreground, a scene in which a straw-hatted farmer is selling produce from baskets. There are squashes and such in some of the baskets, but the basket at the lower left appears to contain birds.

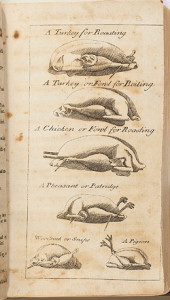

If these are pigeons, the purchasers would have no shortage of directions for selecting a pigeon and a choice of methods for its preparation in cookbooks of the period. But as varied as were the methods of preparing pigeon offered by Child in The American Frugal Housewife (1829 and many later editions) or Lee in The Cook’s Own Book (1832), many of these receipts had first appeared in print as early as 1747 in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, published in London. They can be traced through editions of Susannah Carter’s The Frugal Housewife (London, 1765, and later eds.). When Carter’s cookbook was reprinted in Boston in 1772, Paul Revere engraved two plates showing the preparation of some eleven meats, including the pigeon. Carter’s recipes were a source for authors of other cookbooks. One was Maria Rundell and her London publisher, John Murray, who produced A New System of Domestic Cookery, Formed Upon Principles of Economy, and Adapted to the Use of Private Families (1803, the first of many eds. in England and the United States). Another was Amelia Simmons, whose list of wild fowl and selection criteria in American Cookery (Hartford, 1796, and other eds.) includes such birds from the wild as duck, woodcock, snipes, partridge, plover, black birds, and lark, in addition to pigeon.

Pigeon appears in the first American edition of Carter’s The Frugal Housewife (1803) as part of the general information for the cook and again in the recipe section. Monthly bills of fare recommend pigeon in most months between March and November. A choice for an August supper might be roast chicken or pigeon with asparagus or artichokes; for a dinner in September leg of lamb or roast goose might be followed by pigeon pie. Pigeon returned to the dinner menu in November. Carter also provides suggestions “for the proper arrangement of two courses,” and some editions included an illustration of how to place the platters on the table. Many of Carter’s recipes, including those for pigeon, appear in American imprints of Rundell’s work offering an overview of their preparation on both sides of the Atlantic for both fancy and family dining. Rundell speaks to the versatility of pigeons. “Pigeons may be dressed in so many ways, that they are very useful. The good flavour of them depends very much on their being cropped and drawn as soon as killed. No other bird requires so much washing.” For a grand occasion, for instance, the pigeon in jelly “has a very handsome appearance in the middle range of a second course; or when served with the jelly roughed large, it makes a side or corner thing, its size being then less. The head should be kept up as if alive, by tying the neck with some thread, and the legs bent as if the pigeon sat upon them.” Pigeons left from dinner the day before may be warmed with gravy and served with stuffing on the side, or made into a pie; in either case, care must be taken not to overdo them, which will make them stringy. The cook was advised to reheat the meat in gravy and serve with forcemeat balls on the side, instead of as stuffing. Pigeon might be broiled, roasted, pickled, potted, or prepared in jelly. With so many cooking techniques possible, the pigeon was a very versatile bird.

![Fig. 2. Male and female passenger pigeon. Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology, or: The natural history of the birds of the United States, 9 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1808-14) 5: 110-13. The accompanying text refers to the "vast numbers" that are shot and the "waggon loads of them that are poured into the market …[so that] pigeons become the order of the day and dinner, breakfast and supper until the very name becomes sickening." Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/216-300x222.jpg)

Pigeon, as we have seen, was readily available, so these recipes remained useful even for American authors who were not suggesting extensive and elaborate meals. Child recommended roasted, potted, or stewed pigeon.

“Potting is the best, and the least trouble. After they are thoroughly picked and cleaned, put a small slice of salt pork, and a little ball of stuffing, into the body of every pigeon. The stuffing should be made of one egg to one cracker, an equal quantity of suet, or butter, seasoned with sweet-marjoram, or sage. Flour the pigeons well, lay them close together in the bottom of the pot, just cover them with water, throw in a bit of butter, and let them stew an hour and a quarter if young; an hour and three quarters if old. Some people turn off the liquor just before they are done, and brown the pigeons on the bottom of the pot; but this is very troublesome, as they are apt to break to pieces.”

To roast pigeon, Child directed the use of a spit. After preparation (stuffing), pigeon would cook in “fifteen minutes before a smart fire.” Carter and Rundell both describe preparing the pigeon for a lifelike presentation, either by surrounding them with a nest of spinach or artichokes or molding them in jelly to look as if they had paused during flight.

Pigeon was not only for family meals. It appeared on the Bill of Fare for the American Antiquarian Society’s semiannual meeting of April 25, 1866, held at Boston’s Parker House, where three wild birds comprised its game course: Brandt, Black Ducks, and Wild Squabs. (The gentlemen present followed this with a selection of salmon, mutton, capers, pork, lamb, beef, turkey and chicken.) By the 1890s, however, the squab were gone from the American Antiquarian Society’s menu and were replaced by snipe and plover.

As is well known by now, the passenger pigeon went from plentiful to extinction in the United States before the nineteenth century ended. Squab is still available to cooks and a lively tradition of preparing and eating this delicacy continues. In fact, as I reflected on this piece, I kept coming across contemporary mentions of pigeon—in the culinary sense. For Christmas I received a copy of Amanda Hesser’s Essential New York Times Cookbook. Hesser warned her readers not to use it for academic research and then I happened upon her words of praise for Craig Claiborne, the definer of “food chic,” who “expanded his areas of interest to include foreign cuisines with an unprecedented zeal.” The example Hesser chose to illustrate his international interest: “Pakistani pigeons and pilau.”

Hesser omitted the recipes, but they may be found in Claiborne’s New York Times Cookbook in a section titled Game Birds that opens with several recipes for squabs. His description is tantalizing: “A squab is a cultivated pigeon too young to fly and is one of the finest of esculents.” He recommends substituting Rock Cornish game hen in these recipes, “for squabs are expensive.” Formerly the meat of any pigeon or dove species would have been used, among them the wood pigeon, the mourning dove, and the now-extinct passenger pigeon. Now domestic pigeons are raised to one month of age and sold as squab, a business that has its own rich history extending for seventy-five years and more. The Palmetto Pigeon Plant of Sumter, S.C., is an example of a modern business that, in the absence of wild flocks to “harvest,” raises pigeon and their kin for research and the table. They are in the business of “supplying millions of squabs throughout the world.” Proudly, they reveal that “our squab has been served on plates of Kings and Queens, Presidents, Prime Ministers, dignitaries, and other lovers of great food because of the quality they demand.”

Palmetto Pigeon’s hand-processed and vacuum-sealed squabs are a far cry from the nineteenth-century market basket pigeon, and yet Claiborne’s cooking directions are still a bridge to the nineteenth-century kitchen. Of the four recipes for squab, three could easily, more easily perhaps, have been prepared in an early nineteenth-century kitchen—roast stuffed squabs, squabs with Madeira sauce, and potted squabs. The other, well, that’s Claiborne’s (and Hesser’s) spicy, international recipe.

The first step in the preparation of the roast squab is to truss the bird. I read Claiborne’s directions, following in my imagination: using a string, tie down the wings, then the legs, loop around the tail and cross over the bird’s back, make one more pass that secures the wings before making a second loop to “tie the neck skin.” And then I wondered, why do all this only to brown the bird in a skillet? Why not use the loop, as Mrs. Rundell would have recommended to the hearth cook, to attach the bird to a twisted string hung from a nail over the hearth? How much simpler that would have been than browning the bird in a skillet before roasting it in the oven. In the simple, old-fashioned way, the whole bird would have been roasted in a half hour or even half that time with a few twists of the string in front of a hot fire. In a similar vein, the recipe for Roast Squabs with Madeira Sauce is a variant of the recipe above, using a wine imported and readily available in town and country in the early national period. The drippings in a pan under the bird (whether in the oven or at the hearth) are the basis for the sauce made with equal amounts of Madeira and brown gravy.

Claiborne’s recipe for potted squabs calls for either a casserole dish or a Dutch oven. Again, one can imagine the nineteenth-century housekeeper directed by Mrs. Child browning the bird and arranging the vegetables, herbs, and broth around it. Using a Dutch oven for the ingredients, she would put the iron lid on the iron pot, set it on a bed of coals and place a shovelful of coals on top of the lid. Hearth or oven, the timing would be roughly the same—45 minutes to 60 minutes.

During his tour of eastern North America selling subscriptions to the octavo edition of Birds of America then in production, Audubon found himself with a leisurely mid-August Sunday in New Bedford, Massachusetts. He took a morning walk and went to worship at the old Unitarian Church (“No Organ and vile fiddlers!” he scoffed). After he had “Dined on Wild Pigeons now plentiful hereabouts,” he took a “Walk of about 7 miles with 4 Gentlemen, to several ponds, but saw very few birds … and eat as many huckleberries as I could wish.” It’s amazing how much better one can feel after a good dinner, even if we are left to wonder how that pigeon was prepared.

Further reading:

Jack Larkin and Caroline F. Sloat, A Place in My Chronicle: The Diary of Christopher Columbus Baldwin, 1829—1835 (Worcester, Mass., 2010). The entries cited are from January, July, and September 1830; July and September 1831; and April 1832, just as he was preparing to take up his appointment as AAS librarian. Birds of America is available (or scarce) in a variety of formats. The edition of Birds and the Ornithological Dictionary in the Darlington Library collection at the University of Pittsburg have been digitized and are searchable. The American Antiquarian Society holds a set of the octavo edition (1840-44). On the extinction of the passenger pigeon, see, for example, Christopher Cokinos, Hope is the Thing with Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds (New York, 2000) and Allan W. Eckert, The Silent Sky: The Incredible Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon (Lincoln, Neb., 2000). Andrew Blechman’s Pigeons: The Fascinating Saga of the World’s Most Revered and Reviled Bird (New York, 2006) is a sweeping historical account of these birds. Blechman’s quest to chronicle the transformation of this once prized and now reviled creature provided him with a series of fascinating experiences that reveal not only how much more there is to the pigeon than the scavenging street pigeon, but even includes an account of the Royal Pigeon Handler employed by England’s Queen Elizabeth II.

There are many editions of the popular Anglo-American and American cookbooks of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries cited above. Susannah Carter, The Frugal Housewife or Complete Woman Cook (Boston, 1772); Maria Rundell, some editions are titled American Domestic Cookery: Formed on Principles of Economy, others Experienced American Housekeeper: Domestic Cookery…Formed on Principles of Economy. There are many American editions of both titles and the illustrations include a pigeon ready for cooking. Cookbooks by Lydia Maria Child, The American Frugal Housewife (Boston, 1832), and Mrs. N.K.M Lee, The Cook’s Own Book (Boston, 1833), include recipes for pigeon, and both appear in many editions. The recipes by Craig Claiborne appear in The New York Times Cookbook (New York, 1990).

Sources for farmed squab include operations with a long history (http://www.palmettopigeonplant.com/) to more recently established businesses. Meat is available for shipment in many countries, and it is also possible to buy a farm: see, for example:http://www.schuhfarms.com/thefarm.html.

Hotel menus from Boston and New York and, to a lesser extent from restaurants in the south and west, form the basis for an article by Paul Freedman, “American Restaurants and Cuisine in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” New England Quarterly 84 (2011): 5-59. The appendix, derived from surviving menus from 1859 to 1865 for New York City’s Fifth Avenue Hotel, is an alphabetical list of entrees. Pigeon appears on fifty menus in twelve separate preparations. However, some of these vary only by sauce, such as wine (Madeira, port, or not identified) or tomato. Freedman indicates that some favored entrees, such as canvasback duck, became scarce and were served only on special occasions by the end of the century. Finally, for vegetarians and others who might be dubious about pigeon, he finds that macaroni, frequently and comfortingly with cheese, was a standard item on the menus scrutinized for his essay.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.3 (April, 2011).