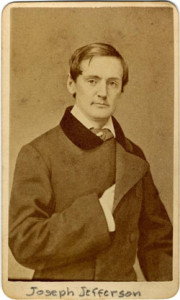

When I picture Edwin Booth I see those American actors, most of them born in his century, who were destined to wander. I see Joseph Jefferson, condemned to tour the country as Rip Van Winkle for forty years until death freed them both; I see James O’Neill, trapped in the role of the Count of Monte Cristo, a part he and his son Eugene both came to despise; I see Minnie Madden Fiske, doomed from the age of eight to a life in transit. I imagine the minstrel singers and vaudevillians who plied their tricks from one town to the next and the “Tommers” who spent whole careers on the road acting out Harriet Beecher Stowe’s tale of life among the lowly. The actress Fanny Kemble, writing in 1847 of her woes on the American road, complained of being made sick by auditoriums with walls as “thin as my stockings” and of her “wandering and homeless life.” Moths drawn to a fickle light, these men and women moved from theater to theater along a route hewn by fellow players who couldn’t afford to go home, or didn’t know how, or had no home.

Eugene O’Neill, born in a hotel room while his father was on tour, captured the roaming predicament. The actor on the road, he said, “doesn’t understand a home. He doesn’t feel at home in it. And yet, he wants a home.” Even a fan as avid as Walt Whitman had his beef with a system in which stars flitted about the country, “playing a week here and a week there, bringing as his or her greatest recommendation, that of novelty.” Yet this drafty system brought thrills to people across the country who were starved for entertainment and supplied a new nation with the mythic figures it needed: Buffalo Bill, Jim Crow, Little Eva, the Headless Horseman, Evangeline.

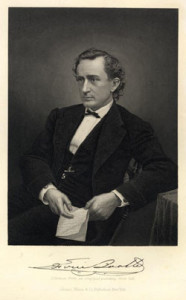

Edwin Booth, like his brothers Junius Brutus Jr. and John Wilkes, was born into the trade. The boys’ mad, alcoholic father, Junius Brutus Sr., spent most of his life on the road and died there while en route to a gig in Cincinnati. “There are no more actors!” cried orator Rufus Choate on hearing of the elder Booth’s death. But Choate was wrong. Booth’s third son, Edwin, a gentle child who seldom smiled and rarely spoke, had taken up his father’s mantle, even though Junius Sr. had sworn he wanted this beautiful boy to have nothing to do with the stage.

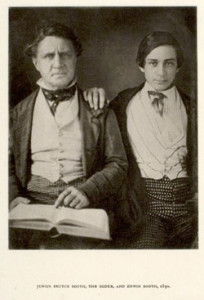

Whatever chance young Edwin had at an ordinary life vanished in his teens, when he became his father’s de facto guardian. Left to himself, Junius Sr. wrought havoc offstage and on. As Hamlet he was capable, when drunk, of abandoning Ophelia and climbing a ladder where he’d sit howling until a stage manager hauled him down. Managers learned to lock Booth up ahead of time to keep him sober for his performances. Absent liquor he was a master, funny and feral at the same time, so intense that actresses sometimes shrank from him in fear. Whitman said of Junius Sr., “The words fire, energy, abandon found in him unprecedented meanings.”

Edwin, small, frail, melancholic, was no match. He shared his father’s heart-shaped face and radiant eyes but lacked his wildness, the abandon that beguiled Whitman. Edwin’s passion was tempered by intellect. “I am conscious of an interior personality standing back of my own, watching and guiding me,” he told a friend. His father may have felt that way about Edwin. On tour the teenager did his best to rein in Junius Sr., tracking his movements, keeping him out of bars, sitting backstage night after night waiting for his father to exit the stage. Perhaps inevitably, Edwin learned all of Booth’s plays, and when the time came, he easily stepped into one. It was the fall of 1849, and he was nearly sixteen. A stage manager in Boston asked if he would play Tressel to his father’s Richard III, and Edwin agreed. He’d long since memorized the part, listening through the dressing-room keyhole “to the garbled text of the mighty dramatists” whose works filled his father’s repertoire. That night in Boston, Junius Sr. gave his own spurs to Edwin to wear onstage, and afterward the older Booth “coddled me,” Edwin remembered, “gave me gruel . . . and made me don his worsted night-cap”—rare gestures of fatherly love.

On the night of Edwin’s birth, meteors had tumbled from the sky above Junius Sr.’s Maryland farm, and people thought the heavens were bursting. The infant arrived with a caul, and the slaves who worked the Booth farm predicted he would one day see ghosts. They also believed Edwin would be guided by a lucky star. Locked as well in that strange prognostication, it seems, was a fated sadness, a sense Edwin himself had, for most of his life, that nothing would turn out right.

Within five years of Edwin’s stage debut Junius Sr. was dead, and Edwin was a star on the stock circuit. He played snowbound mining camps, lived briefly in a hut outside San Francisco, toured the Pacific islands, and eventually made his way back east where he took on his father’s most famous role, the deranged charmer Richard III. Brother Junius Jr., meanwhile, became a theater manager, sister Asia married an actor, and in 1855 seventeen-year-old John Wilkes Booth made his first stage appearance. Before long, both John and Edwin were living on the road. “Starring around the country is sad work,” Edwin wrote an acquaintance, adding that John was “sick of it.” So, for that matter, was Edwin. He urged his daughter and only child to learn to ice-skate, because in his own childhood he’d had no chance to enjoy sports. “For I was traveling most of the time,” he told the girl.

Edwin was nearly thirty when Edwina Booth was born, in England. Like Eugene O’Neill, she arrived on the road while her father was touring. Her birth came one month after the start of the American Civil War, and lest anyone mistake her—or her father’s—allegiance, Edwin hung a Union flag over the infant’s bed.

Her mother, Mary Devlin, had been an actress before marrying Booth. They’d met on the road, in Richmond, Virginia, when she played Juliet to his Romeo, but she’d given up the stage to be Edwin’s wife. He worshipped her. “My youth began with my marriage,” he once said, tellingly. When they returned to the United States after their British tour, they split their time between a rented house in Boston and a hotel in Manhattan.

In early 1863, when Edwina was not yet two, Mary Booth contracted pneumonia. Edwin was performing in New York at the time; Mary remained at home in Boston. Like his father, Edwin had begun drinking, and on the evening of February 20th he was too drunk to open the telegram urging him to come home. By the time he gathered his senses and boarded a train for Boston, it was too late. He arrived to find Mary dead, at twenty-three, a white cloth tied around her neck and chin. Booth never forgave himself. His mother and brother John Wilkes stood beside him at Mary’s funeral; afterward, Edwin renounced liquor for good.

“I wish to God I was not an actor,” he told a friend in the first raw months after Mary’s death. “I despise and dread the d–d occupation; all its charms are gone and the stupid reality stands naked before me. I am a monkey, nothing more.” But there was no other way to support Edwina, and so seven months later Edwin returned to the stage, as Hamlet, another wanderer haunted by family ghosts.

There is a kind of actor who inhabits his role rather than himself. His true life takes place onstage. Only by occupying someone else’s drama do such men and women gain the extra layer of skin needed to express themselves. (Hence the derivation of the word “personality” from the Latin persona, or mask.) When an actor becomes identified with one particular role, the phenomenon is both magnified and debased. If he plays the part for years, his comfort with the character may give way to fatigue and contempt.

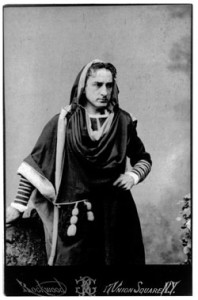

I imagine this is how Booth experienced Hamlet. It became his signature role. “You see . . . he is Hamlet—melancholy and all,” John Wilkes Booth said of his older brother. When Edwina Booth heard the word “omelet” for the first time, she cried, “That’s Papa!”

Surely Booth saw the parallels with his own life, and although he insisted it was his father, Junius, who most resembled the doomed prince (“great minds to madness closely are allied”), it was in fact Edwin who best embodied the part. Despite his talent for expressing the emotions of others onstage—people thought him the greatest tragedian of the nineteenth-century American theater—Edwin Booth was somehow marooned from his own feelings. When he tried to thank audiences publicly for their applause, he shrank back and could only mutter inarticulate sounds. He undoubtedly had, as Hamlet has, “that within which passeth show,” but something, some ghost or fear or remembered trauma, prevented Booth from ever revealing what lurked within. Like Hamlet, he needed the artifice of theater; he needed disguise to be himself.

In late 1864, Edwin Booth embarked on a one-hundred-night run of Hamlet that captivated the American press. Harper’s wrote, “His small, lithe form, with the mobility and intelligent sadness of his face and his large, melancholy eyes, satisfy the most fastidious imagination that this is Hamlet as he lived in Shakespeare’s world.” Booth’s performance became the benchmark for a half-century of American Hamlets.

Any pleasure Edwin might have taken in this achievement vanished on April 14, 1865, when his brother shot Abraham Lincoln in a theater in Washington, D.C. Edwin heard the news in Boston, where he’d been performing, and immediately went into hiding, afraid for his life. (Some reports erroneously pegged him, not John, as Lincoln’s assassin.) Disguised in a cloak and low-slung hat, Edwin snuck down to New York to be with his bereaved mother, all the while believing his acting career finished. “For the future—alas,” he informed the public in a nationwide advertisement, drafted by an acquaintance and published a week after Lincoln’s death, “I shall struggle on in my retirement bearing a heavy heart, an oppressed memory and a wounded name—dreadful burdens—to my too welcome grave.”

U.S. Marshalls searched his trunks and placed Edwin under house arrest; hate mail streamed in. Typical was a letter signed “Outraged Humanity”: “You are advised to leave this city and this country forthwith. Your life will be the penalty if you tarry 48 hours longer . . . We hate the name of Booth.”

He was doubly exiled now: banished to the road and banished from it, a pariah ashamed to bear his own name. “Who has not deep in his heart/ A dark castle of Elsinore,” the French poet Vincent Monteiro asks. “In the manner of men of the past/ We build within ourselves stone/ On stone a vast haunted castle.”

Edwin remained in seclusion for the better part of a year—through his brother’s capture and death, through the trial and execution of John’s co-conspirators, through Lincoln’s long funeral procession, along a route countless American actors had plied. “I have lost the level run of time and events, and am living in a mist,” Edwin wrote to a friend. The actor rarely went out except under cover of darkness. Physically drained, grief-stricken, shamed, he burrowed into himself. For the first time since his teens, Booth stayed home.

And then, eight months after the assassination, the mist lifted, or more accurately financial desperation set in, and Edwin announced his intention to return to the stage. Without the theater, he seemed to realize, he did not exist. He told an acquaintance, “I have huge debts to pay, a family to care for, a love for the grand and beautiful in art, to boot, to gratify, and hence my sudden resolve to abandon the heavy, aching gloom of my little red room, where I have sat so long chewing my heart in solitude, for the excitement of the only trade for which God has fitted me.”

Police stood guard outside New York’s Winter Garden Theater on the evening of January 3, 1866. Rumors had circulated that Booth would be shot the minute he walked onstage that night. Earlier in the week the New York Herald had denounced the actor’s “shocking bad taste” in choosing to resume his career and had suggested the most appropriate role Booth might play was that of Caesar’s assassin. But Edwin chose to appear in Hamlet, a play that begins with a political assassination, and when the curtain rose that night on the second scene and the audience spotted him onstage, his head bowed, they stood and cheered and tossed bouquets of flowers at his feet. For a long time Edwin said nothing; then he began to act. From this performance he went on to present dozens more; he resumed touring and spent the next twenty years traveling around the country. The South, especially, loved him, and Booth’s managers sometimes had to lock his private rail car to keep fans at bay. There was only one place where Booth refused to perform: Washington, D.C. His brother’s deed had effectively banished him from that city.

Central to the Japanese Noh theater, according to theater historian Marvin Carlson, “is the image of the play as a story of the past recounted by a ghost.” Although few would have admitted it, most people who went to see Edwin Booth perform went to see his brother, too, to see the specter of Lincoln’s killer. For the rest of his career this was part of Edwin’s mystique, and he knew it. Each time a newspaper article announced a forthcoming appearance by the brother of Lincoln’s assassin, it meant a “most brutal ghoul-feast,” Edwin confessed to a colleague, “flaunting in my face buried cerements raked up by these hyenas. Each little piddling village has stabbed me through and through.”

Edwin never spoke to anyone of his brother John, avoided all talk of Lincoln. Late one night he dragged John’s trunk to the basement of a theater and ordered a servant to burn everything in it, costume by costume, prop by prop, pictures, letters, silk stockings. Friends worried about depression, and even Edwin alluded to it. Photographs indicate the depth of his gloom: narrow lips, hawk nose, brooding eyes. Actors who played opposite his Hamlet grew fearful when he feigned seeing the ghost of his father.

Seeking, perhaps, to redeem his name, Edwin sank millions into a theater of his own, The Booth. But the enterprise was a failure. His second marriage—to another actress named Mary who had also played Juliet to his Romeo—collapsed after the death of the couple’s infant son and Mary’s subsequent descent into madness. The one constant in Booth’s life was his daughter, Edwina, and in time the sons she bore, whose buoyant presence lightened his old age.

In the last years of his life Edwin built a home for actors, The Players, on Gramercy Park in New York City. He wanted performers to have a place to convene and be treated with respect. “I do not want my club to be a gathering place of freaks who come to look upon another sort of freak,” he declared, and promptly sought—and got—memberships from the likes of Samuel Clemens, Pierpont Morgan, and William Tecumseh Sherman, along with scores of players. Booth was the club’s first president; Timothy Hutton holds that post today. Peruse the ranks of members whose names hang inside the club’s main door and you’ll see some of the many wanderers who found a home inside this building: Joseph Jefferson, George M. Cohan, Clark Gable, Eugene O’Neill.

Here, in a suite of upstairs rooms inside this beautiful brownstone, Edwin Booth died on June 7, 1893, at the age of sixty, his daughter at his side. Moments before his death a thunderstorm struck—as at birth, a celestial omen—and the lights went out. “Don’t let father die in the dark!” Edwina screamed, but when the lights came back he was gone. The mass of reporters who’d gathered outside on the sidewalk, waiting for word of the actor’s condition, filed their sad stories. Not long before, Booth had told friends he was “tired of traveling,” that he was waiting for his “cue to quit.”

The actor who’d passed his life in dressing rooms and hotels had found a home at last, and it remains his home today, the rooms where Booth lived and died eerily preserved just as they were more than a hundred years ago. I visited them a couple of years ago with my husband. We saw Booth’s bed and desk and tobacco pipes, photographs of his first wife, his daughter, his mother and father. And above the bedside table, two additional—and for me unexpected—photographs: one of his second wife and one of his brother John. “A monument to madness?” I asked curator Raymond Wemmlinger, and he said he’d often thought so.

Edwin Booth reminds us that to live is to wander, to etch a spot in the world and then to move on. “Life is itself exile,” writes the novelist William Gass, “and its inevitability does not lessen our grief or alter the fact.” Hamlet, who flares and then fades, much like the stars at Edwin’s birth, tries to prove otherwise by mocking death, but in the end it traps him, has trapped him all along. Booth grasped this instinctively, and it helps explain his magnetism in the role. One of his contemporaries said, “He made us believe in the spirituality of Hamlet, in his kinship with the beyond.” Booth’s ultimate allegiance was to the dead, to the ghosts he was destined to encounter, and in Hamlet he found a means of expressing that allegiance. All along he understood—better than most—that he was just passing through.

A statue of Booth as Hamlet stands in the middle of Gramercy Park. It was unveiled in 1919 by Booth’s grandson, as some five hundred New Yorkers looked on. The bronze is imposing, a fitting nod to an actor who dominated the American stage—many American stages—for half a century. But the gates to the park are locked, and only residents of the immediate neighborhood have keys. I could do nothing but stand outside and pay my respects from a distance. Even in death, Booth’s exiles endure.

Further Reading:

For an overview of the nineteenth-century American theater, see both volumes of The Cambridge History of the American Theatre (Cambridge and New York, 1999) and in particular, Thomas Postlewait’s essay, “The Heiroglyphic Stage: American Theatre and Society, Post-Civil War to 1945,” in volume 2. I’ve drawn cultural and historical details from both David S. Reynolds, Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (New York, 1996) and Jay Winik, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (New York, 2001).

In American Gothic: The Story of America’s Legendary Theatrical Family—Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth (New York, 1992), Gene Smith tells the story of the star-crossed Booth family with high drama. On his own, Edwin Booth has drawn biographical scrutiny since before his death. Among such accounts, his sister Asia Booth Clarke’s The Elder and the Younger Booth (New York, 1882) is notable—and heartbreaking—for what it leaves out; for the story behind her story, see Terry Alford’s introduction to Asia Booth Clarke, John Wilkes Booth: A Sister’s Memoir (Jackson, Miss., 1999). Booth’s friend William Winter offers eloquent testament to the actor’s gifts and to his suffering in Other Days. Being Chronicles and Memories of the Stage (New York, 1908) and Life and Art of Edwin Booth (New York, 1894). Other biographies include Charles Townsend Copeland’s Edwin Booth (Boston, 1901); Richard Lockridge’s Darling of Misfortune: Edwin Booth (New York, 1932); and Eleanor Ruggles, The Prince of Players (New York, 1953), which inspired a 1955 movie starring Richard Burton as Edwin.

Readers interested in the actor’s art and its powers should consult Michael Goldman’s superb The Actor’s Freedom (New York, 1975). The periodical sources on Edwin Booth are vast and rich; to gain the fullest possible knowledge of the man, however, one must visit The Players in Gramercy Park, where archivist Raymond Wemmlinger maintains an up-to-date library and can unlock the room where Booth breathed his last.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.3 (April, 2008).

Leslie Stainton is the author of Lorca: A Dream of Life (1999) and numerous essays and articles. She is at work on a history-memoir of the Fulton Opera House in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where Edwin Booth performed in 1886.