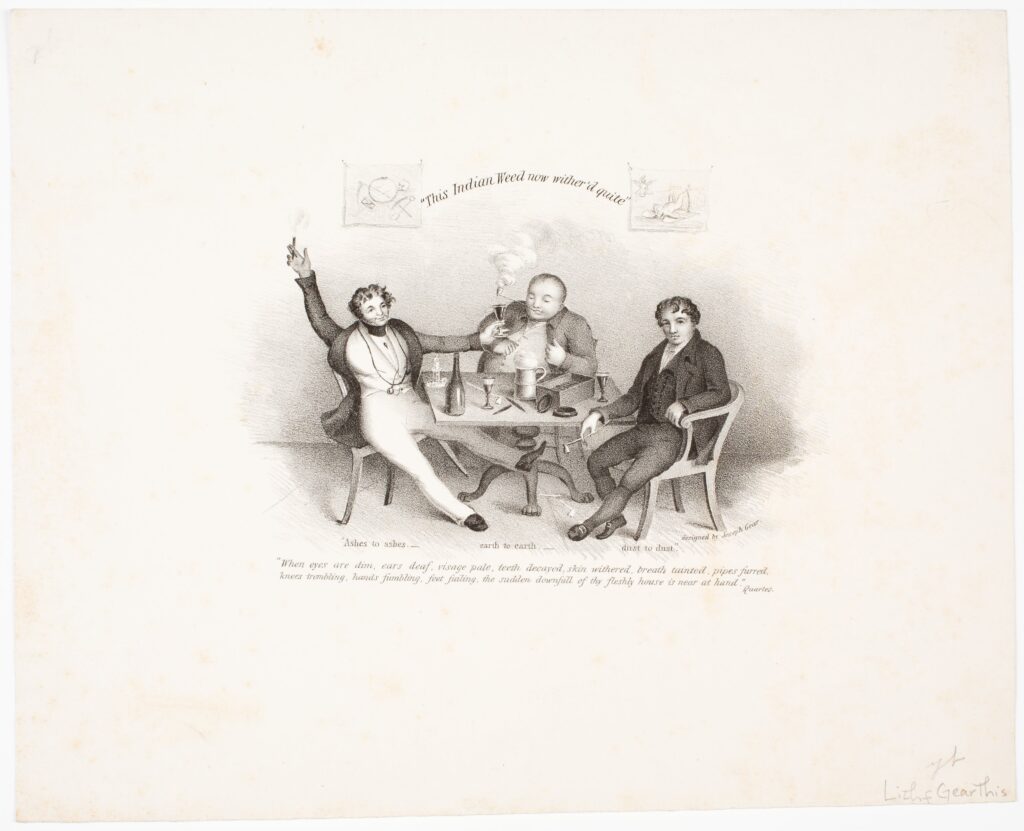

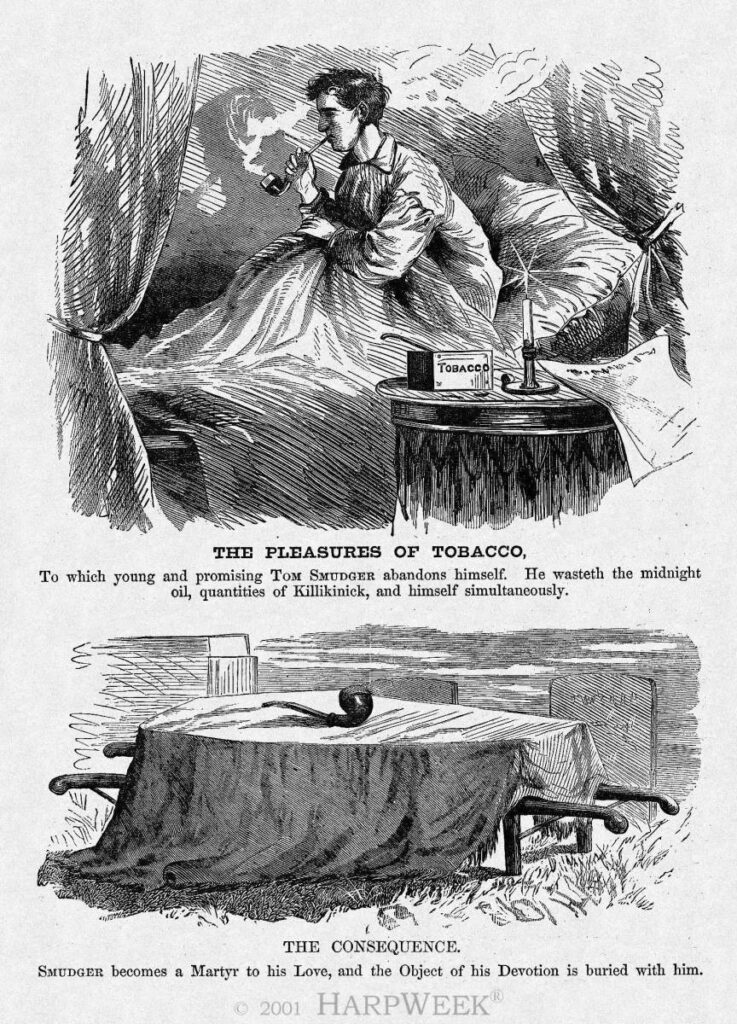

The prints below convey in just two frames a cautionary tale that concerned countless Americans in the nineteenth century. The first frame presents two well-dressed, white, middle-class boys, in a moment of innocent play, experimenting with their first taste of a forbidden fruit, tobacco. The boys, naively curious, are shown puffing on the cigars in hand. Yet, as the second frame reveals, the consequences of this misstep are swift and unpleasant: the boys, reeling from the effects of the tobacco, are seen doubled over, one clutching his stomach in visible discomfort, while their young girl companion looks on, an expression of worry and disbelief on her face.

Puff, Puff? Pass!: The Anti-Tobacco Writings of Margaret Woods Lawrence

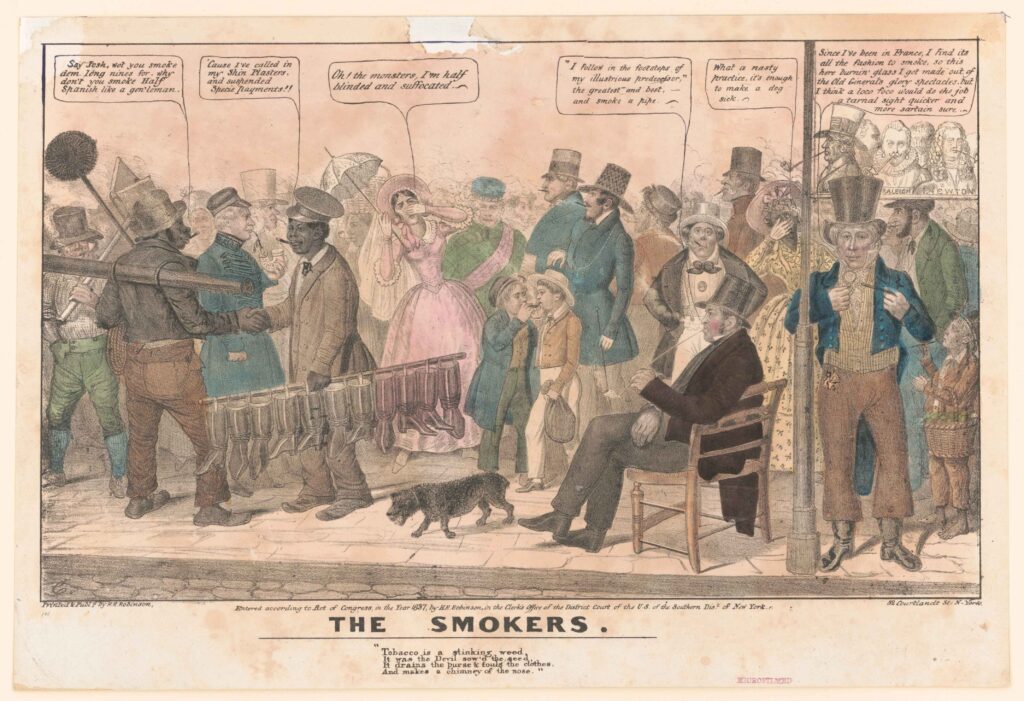

Reformers linked tobacco use to a deterioration of social and familial values, a habit that disrupted the sanctity of the home.

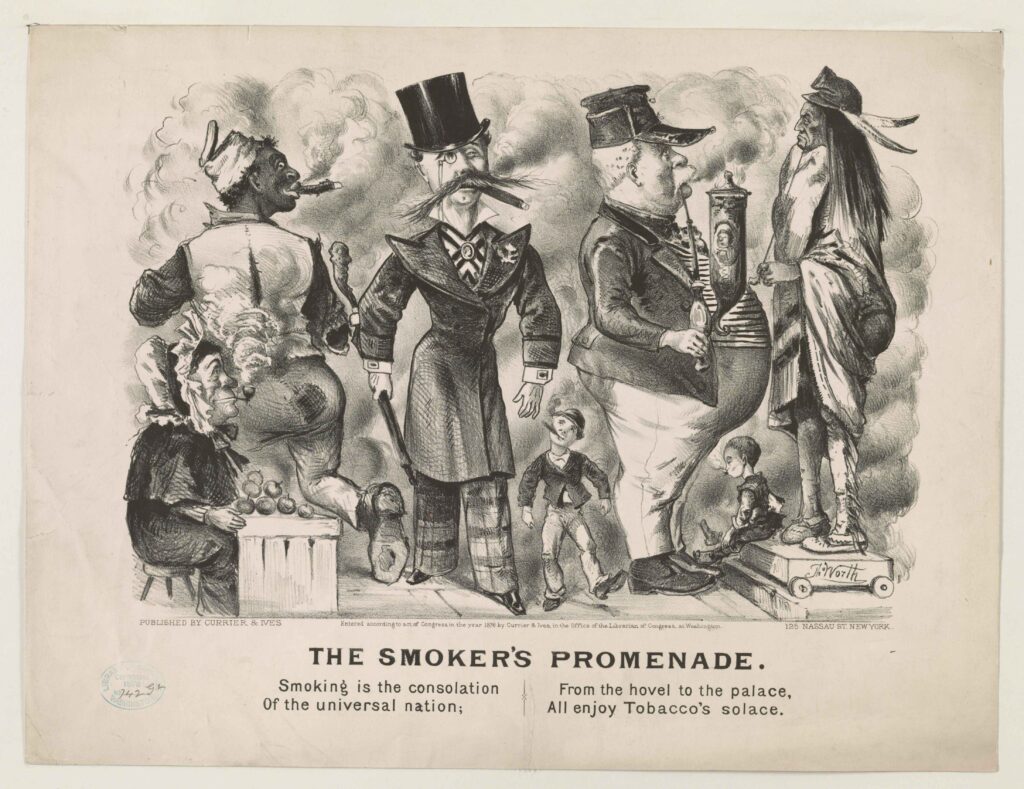

Without text, these prints nonetheless issue a pointed admonition: avoid the tobacco habit! The absence of written commentary allows the imagery to speak for itself, targeting especially the young and impressionable, and their parents. The young girl’s presence in the print is important, too, though she is not partaking. Women were at the forefront of many anti-vice campaigns of the century, notably those championing temperance from alcohol but also abstinence from tobacco. By the latter half of the century, opposition to tobacco was rising rapidly, led not by governmental health directives but by moral conviction and domestic ideals. Figures like Margaret Woods Lawrence believed that tobacco use was not simply a moral failing but a reflection of deeper cultural and economic forces—ones that reformers sought to change but that, like vice itself, proved persistent. Even as these early movements laid the groundwork for future systematized public health initiatives, their impact was uneven, shaped by the same classed and racial biases that would define later governmental efforts at vice control. The imagery in these prints, stark and persuasive, marks an early attempt to instill restraint. Yet, as history shows, the boundaries of “clean living” would continue to be contested, whether in the age of cigarette prohibition, temperance, or, later, the rise of vaping.

In the broader temperance era, dominated by women reformers, tobacco was often seen as yet another corrosive vice, akin to alcohol or gambling in its corrupting influence on character. Reformers linked tobacco use to a deterioration of social and familial values, a habit that disrupted the sanctity of the home. It was a moral battle; tobacco was a barrier to men’s responsibility toward family and a threat to the moral fabric of society. These women—mothers, wives, and sisters—witnessed how men’s indulgence in tobacco and alcohol often led them away from family duties and down a path to moral and spiritual decline.

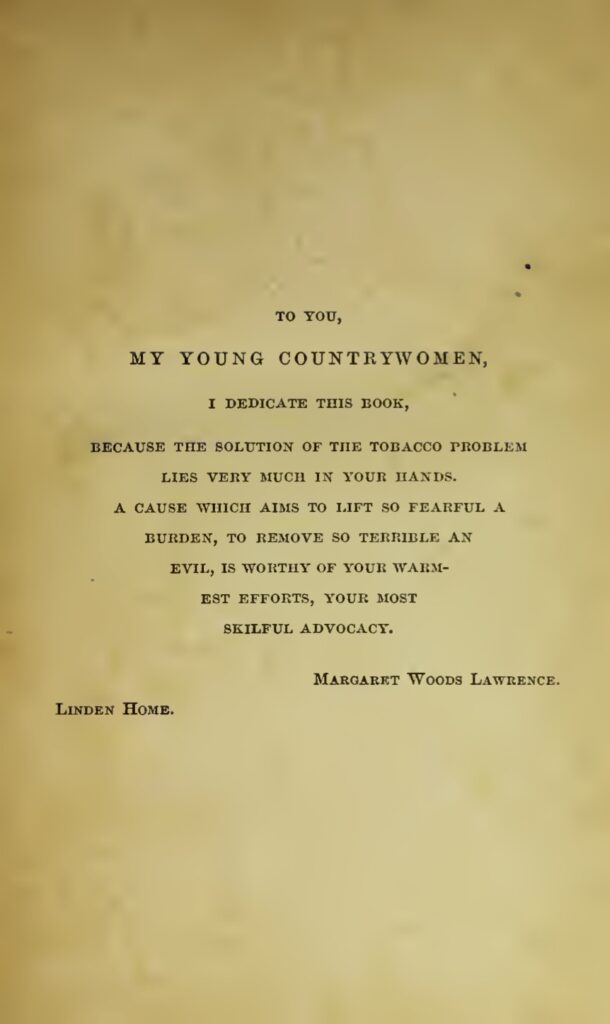

One such woman, mostly forgotten today though prolific of pen in her time, Margaret Woods Lawrence, championed the anti-tobacco cause. Recognizing the vital role women could play in the cause, she dedicated her book The Tobacco Problem (1885) in this way: “To you, my young countrywomen, I dedicate this book, because the solution of the tobacco problem lies very much in your hands.” By the time she wrote Tobacco Problem, Lawrence was already well known, though typically by her pseudonym Meta Lander, as author of sentimental, moral novels such as Marion Graham (1861; revision, 1890) and Esperance (1865) as well as hagiography such as Light on the Dark River (1853), a memoir of Henrietta Hamlin, a missionary in Turkey. Lawrence’s reputation and wide circle of correspondents and contacts ensured that her writings on tobacco and smoking reached a wide audience.

A friend and correspondent of Frances Willard and other reformers, Lawrence possessed an excellent genealogy, one of considerable moral authority, and was of a sisterhood of prominent writers. Born into American Calvinist nobility at Andover, her father was eminent clergyman and professor Leonard Woods, one of the first generation of faculty at Andover Theological Seminary. Though the seminary’s faculty and student body consisted entirely of men, the women who were connected to the place made even longer-lasting contributions to American letters and reform. Another writer of the day, Sarah Loring Bailey, wrote in her history of Andover: “There have been forty professors [in the history of the seminary], but their wives and daughters, six women, have published books which have had a circulation of at least a million copies.” No doubt, Bailey vastly under-represented the circulation of those women’s works (because one of them was Harriet Beecher Stowe), but she rightly emphasizes the wide readership of the reform works penned by the women of Andover.

Margaret Woods Lawrence, one of the more successful of those women, was thus born into an atmosphere and bloodline of moral propagationists, and even her sentimental novels were examples of religious instruction. Her husband was a well-known clergyman as well as a peace advocate, and together they imbued the next generation of their family with the spirit and action of moral reform. Lawrence’s most touching and personal works are of her family, The Broken Bud (1861), written in memory of her daughter Carrie, who died in childhood, and Reminiscences of the Life and Work of Edward A. Lawrence, Jr (1900), a tribute to her son, a missionary, pastor, and social-settlement reformer who died in his early 40s, preceding her in death.

Lawrence’s love and admiration for both her husband and son (their family letters to each other are spirited, funny, and warm) inspired in her a concern for the sons and husbands of others, for American manhood generally, its moral constitution and the example it set. Lawrence did not challenge the privileged position of men in her world, but she did wish to assert her wifely/motherly influence to reform and cleanse the dirtier habits of men. Her influence with her husband and son succeeded; both abstained from tobacco and (eventually) alcohol as well. Lawrence writes with pride of her son who, even in his travels in Europe: “on the tobacco question he was decided, and notwithstanding the constant temptations, he never yielded, even although a surrender would have enabled him to enjoy many discussions from which the nicotine atmosphere drove him away.” That son, Edward Jr., for his part, became fully devoted to the anti-tobacco cause, though he enjoyed occasionally teasing his mother for her tireless work. On finding out she was reading from her Tobacco Problem to patients in a sanitarium, he wrote to her (in a letter she reproduced in Reminiscences): “I feel very much like scolding you. Away at a Health-Cure, yet so full of tobacco. You think you can’t help it, but that is just the trouble. If you dropped one thing, you would take up two more. I shall add that one of the evils of tobacco is that it is wearing my mother out.”

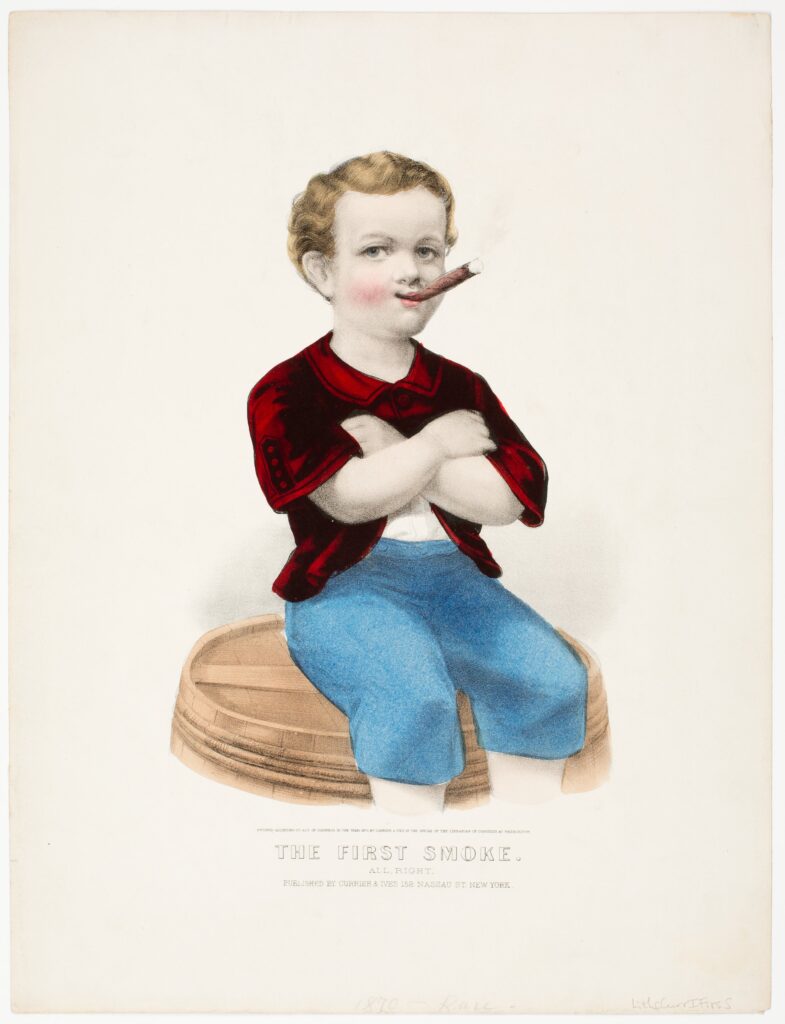

Lawrence’s anti-tobacco reform work, fueled by her personal connections and a profound sense of maternal responsibility, did not challenge the privileged place of men in her society. Instead, she sought to exert her maternal influence to purify men’s habits and guide them toward healthier, morally sound lives. The tobacco cause became her own reformist crusade, aimed particularly at saving impressionable boys from the seductive lure of “the weed.”

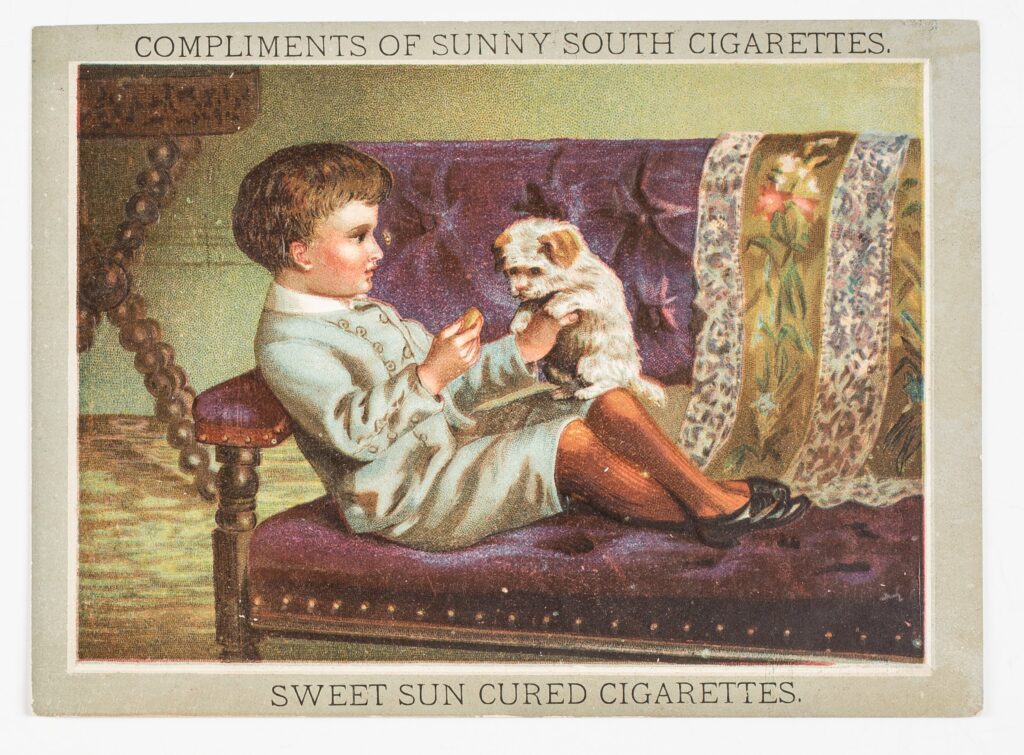

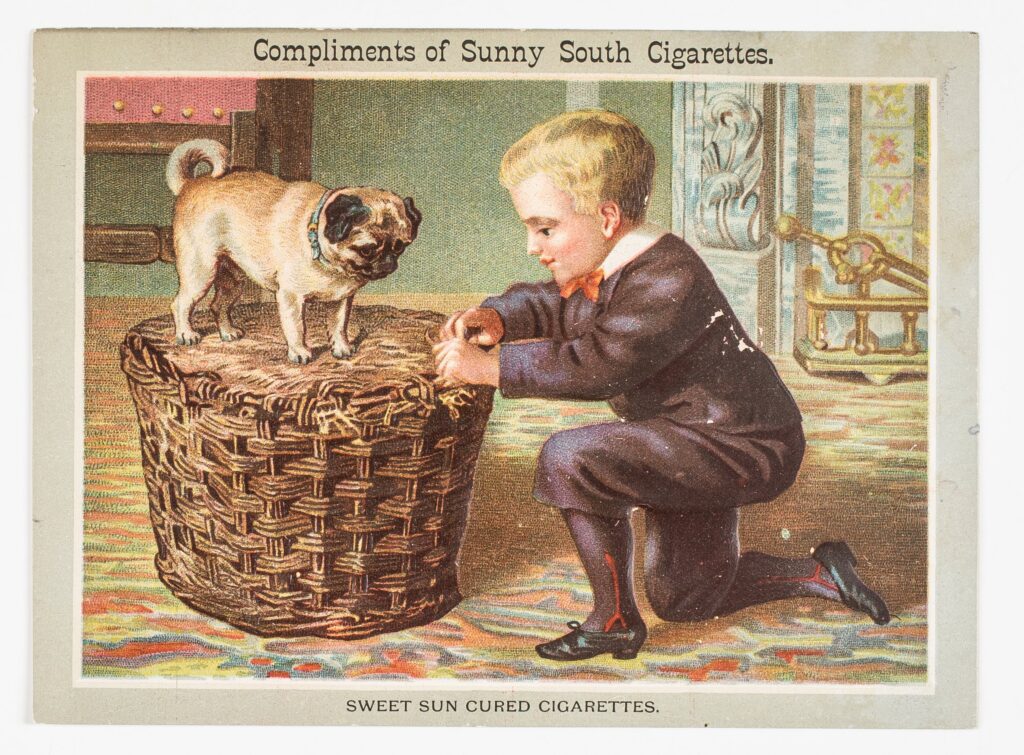

Tobacco companies targeted boys, a practice that infuriated reformers. Trading cards and badges packed with cigarettes enticed young boys—that sort of advertising ploy especially angered Lawrence, worried as she was about the deepening smoking habit among the young. (The famous Honus Wagner baseball card, often cited as the most valuable such trading card, for example, was originally packaged with cigarettes by the American Tobacco Company.)

Amusingly, in her widely circulated The Tobacco Problem, Lawrence praised the advertising cards and tokens proposed and distributed by the Anti-Tobacco League, which itself began a counter-solution by offering “Pledge Cards, Badges and Certificates” to boys who agreed not to smoke. It would be unlikely to find any of those particular enticements competing in price with a Honus Wagner baseball card today, so one suspects that their appeal even then may have paled in comparison to the tobacco cards. Still, many such certificates and badges were issued around the country, achieving some small level of success at least.

Lawrence also decided to directly address the advertising targeting boys. While her lengthy compendium The Tobacco Problem was intended for adult readers (she was encouraged to write it by her friend Frances Willard, whose WCTU had just that year, 1885, instituted a Department for the Overthrow of the Tobacco Habit), she distilled that collection of research on tobacco use into a much shorter pamphlet, “An Open Letter to Boys.” The “Open Letter” was distributed not in book form but as a “penny paper,” a series produced by the WCTU (Lawrence’s “Open Letter” was no. 27) and sold by them for 100 copies for $1. Reformers could thus order a large stack and distribute them widely among boys. In the “Open Letter,” she tells “Tom, or Harry, or whatever your name may be,” many horrifying accounts of tobacco use, including this: “Some people may say that [tobacco] will do you good. A boy of fourteen who had a severe toothache was told this; so he bought fifteen cents’ worth of tobacco, and, smoking it all, he fell down senseless and died.”

Her longer work addressed men, not boys, and often focused on the man’s role as provider for his family. Lawrence regularly referred to the costs associated with tobacco use, emphasizing that the money men spent on its consumption could instead be used for beneficial societal investments. She liked to draw dramatic, attention-grabbing examples, such as tobacco funding being redirected to finance “two railroads round the earth” or building “a hundred thousand churches.” But even more than the lost opportunity of social investment, Lawrence repeatedly remarked on tobacco’s financial toll on the household, where wives often sacrificed because of their husbands’ smoking habits, arguments alcoholic opponents also frequently presented. “How many a family is cramped for the necessaries of life,” she writes, “because the husband and father will not give up his cigar!” On the other hand, once a man gave up his habit, family fortunes saw a much better chance of rising. Lawrence reported on one husband and father, who, after realizing how much money he was spending on tobacco, decided to quit. He began depositing his saved tobacco money, and, eventually, he used this fund to build a house, which he humorously named his “smoke-house.”

Lawrence’s work was a compendium, presenting research from medical men in readable digest form. Tobacco’s physiological effects were an important part of those scientific observations—the outward expressions of inner “soiling,” both physical and spiritual. She not only cited cases of nicotine poisoning, emphasizing its dangers for youth, but also emphasized the moral lesson she inferred from the scientific literature and lectures. For example, she discussed how the experiments of professor C.H. Bumpus showed that tobacco negatively affected the central nervous system of small animals, extrapolating the potential harm to human users—his claim—with her own reading of the situation as one of spiritually lost youth. These early “scientific” observations of Bumpus and the other physicians cited in her work, while anecdotal by modern standards, bolstered her claims about the physical and spiritual risks posed by smoking.

Lawrence’s own educated, upper middle-class family often enjoyed and discussed books, visited art museums, and attended lectures. Those sorts of cultural experiences, she believed, were important for family development. She reminded selfish, smoking fathers and husbands: “Books, music, pictures, excursions with the children to the seaside or the mountains, a thousand and one little refinements and brighteners of the dull routine of life—all are swallowed up by his rapacious maw!” His smoke-filled maw, at that.

Even worse, sometimes far more, was lost than cultural outings. She cited Methodist Episcopal Bishop Harris, for example, who claimed that “the Methodist Church spends more for chewing and smoking than it gives toward converting the world.” No doubt the pastor was sincere in his words; no doubt, too, the anecdote rested even more heavily than the accumulated smoke from his pipe on the Christian man who valued Christian mission work. The scientific observation, paired with the moral and religious anecdote, served as Lawrence’s two-pronged approach to persuading the reader who was both rational and religious.

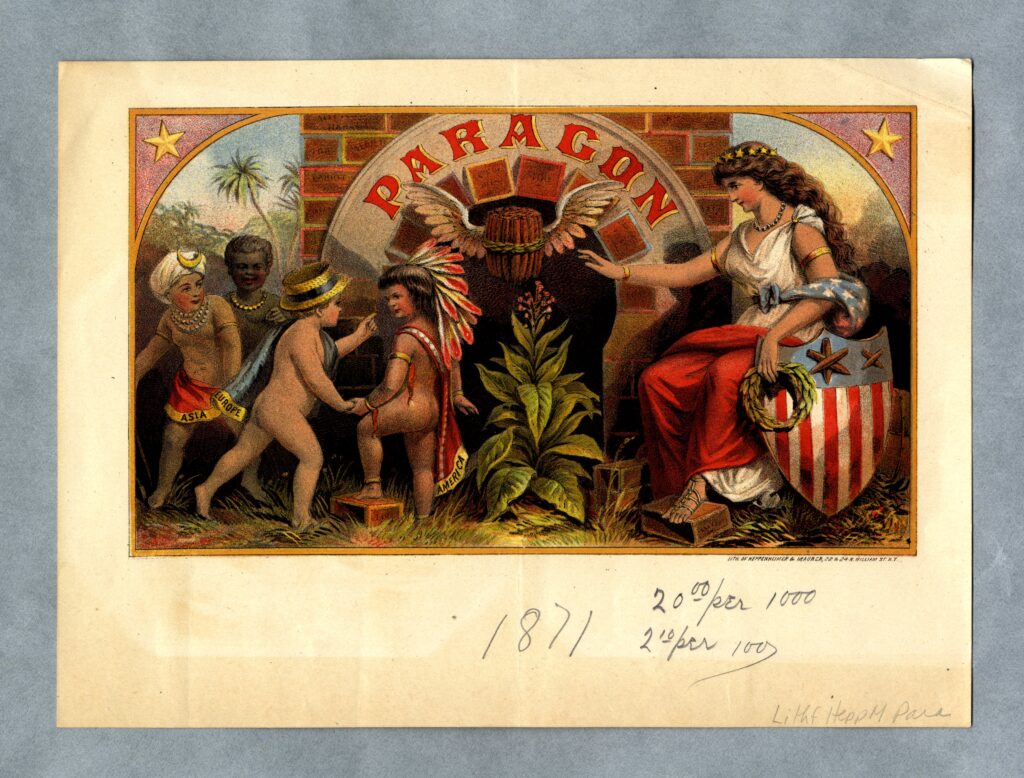

Margaret Woods Lawrence’s work was also intertwined with contemporaneous societal attitudes about class, race, and immigration. Lawrence’s work spoke directly to men of her own class, characteristic of the reform era’s white, Protestant, middle-class sensibilities. In The Tobacco Problem, she shared with that audience concerns regarding urbanization and the association of tobacco with immigrant laborers, particularly in San Francisco’s tobacco factories, where she notes the involvement of “Chinese lepers.” Similarly, Lawrence’s association of tobacco use with “barbaric” practices by indigenous peoples and African laborers reflects broader colonialist and racial perspectives embedded in reformist discourses. Her work never focused on those dynamics, but always, lingering at the window of the first-class rail car was the specter of the smoke of the street and the port, infiltrating “respectable” spaces where it was not wanted by respectable people. If the Black or Chinese laborer or new immigrant was not entirely Other in her Christian economy of a brotherhood of believers, he was, at least, “less than,” it seems, on his way to becoming a clean, sober, smoke-free, respectable citizen, just not there yet.

Probably the most startling comparison Lawrence drew in The Tobacco Problem is equating tobacco addiction with slavery. She wrote bluntly that tobacco users were “as truly slaves as were our Southern negroes” and that their “fetters are as tightly riveted.” Lawrence, friend of many abolitionists including Harriet Beecher Stowe, was no doubt inspired by the success of abolitionists’ writing a couple of decades before. By likening tobacco use to recently abolished enslavement, Lawrence condemned the habit not simply as a personal vice but as a system of control that compels submission from its users. The comparison, rather shocking to our eyes, was nonetheless an often-repeated one at the time.

Lawrence’s alignment with other anti-vice crusaders, such as Frances Willard, reflected her gendered and religious views of the world and her work. While she saw herself as working with faith-based, reform women, she saw herself as under the guidance and instruction of men, particularly pastors and doctors, and she did not directly align herself with secular reformers such as Anthony Comstock. Lawrence’s ethics were always self-consciously Christian ones. By linking tobacco use to a larger framework of societal decay, Lawrence positioned her work within the broader anti-vice movement of the late nineteenth century, though her work remained always a moral authority inspired by her faith.

Though none of Margaret Woods Lawrence’s works remained in print after her death, the anti-tobacco movement she helped pioneer laid the groundwork for later public health campaigns. While her contemporaries may have viewed smoking as a moral failing or vice, her broader critiques—including financial irresponsibility, cultural degradation, and health implications—foreshadowed the systemic approaches to vice control, along with their continued and ever-present classed and racial biases, we see still today. Revisiting her work offers a lens to understand how nineteenth-century reformers grappled with deeply ingrained social behaviors and systemic problems, and how their work—so triumphant on many fronts, including, eventually, alcoholic temperance and suffrage—sometimes failed to convince, initially. While no-smoking zones are common now, and have been for some time—and the smoke-free public transportation we enjoy would have brought joy to Lawrence’s heart—the tempered act of vaping, say, finds a way to sneak into those “clean zones.”

In the decades since the 18th and 21st Amendments, though, the tide has certainly shifted in anti-tobacco’s favor. Though nothing like the (later repealed, of course) 18th amendment crowned the anti-tobacconists efforts, decades later, in 1964, when the U.S. Surgeon General would issue his groundbreaking report on the dangers of smoking. I’m (just) old enough to remember old ashtrays lingering on in cars and even airplanes, but I’ve never been legally allowed to light up on a flight, even as I enjoy a mid-air cocktail or two. No, the anti-tobacconists would not meet much systemic success in the 19th century, yet had she lived an extraordinarily long life and were able to see today’s ubiquitous “No Smoking” signs, or the warnings labels on locked-up tobacco products, Margaret Woods Lawrence and her fellow anti-tobacconists would no doubt be very pleased indeed. Light up? Pass!

Further Reading:

Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover: Comprising the Present Towns of North Andover and Andover (Boston: Houghton, 1880).

Eric Burns, The Smoke of the Gods: A Social History of Tobacco (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006).

Wendy J. Deichmann Edwards and Carolyn De Swarte Gifford, Gender and the Social Gospel (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003).

Washington Gladden, Church and Parish Problems: Vital Hints and Helps for Pastor, Officers, and People Edited by Meta Lander [Margaret Woods Lawrence] (New York: Thwing, 1911).

Jake Frederick, Riot!: Tobacco, Reform, and Violence in Eighteenth-century Papantla, Mexico 1st ed., (Liverpool University Press, 2016).

Meta Lander [Margaret Woods Lawrence], The Broken Bud: Or, Reminiscences of a Bereaved Mother (New York: Carter and Brothers, 1861).

Meta Lander [Margaret Woods Lawrence], Esperance (New York: Sheldon, 1865).

Meta Lander [Margaret Woods Lawrence], Marion Graham: or, “Higher than Happiness” (Boston: Crosby, Nichols, Lee, 1861).

Meta Lander [Margaret Woods Lawrence], The Tobacco Problem (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1885).

Margaret Woods Lawrence, Reminiscences of the Life and Work of Edward A. Lawrence, Jr. (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1900), 71 and 216.

Thomas R. Marshall, Public Opinion, Public Policy, and Smoking: The Transformation of American Attitudes and Cigarette Use, 1890-2016 1st ed., (Blue Ridge Summit: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, 2016).

Carol Mattingly, Well-tempered Women: Nineteenth-Century Temperance Rhetoric (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1998).

James B. Salazar, Bodies of Reform: the Rhetoric of Character in Gilded Age America (New York: New York University Press, 2010).

This article originally appeared in April 2025.

Brian Fehler (Ph.D. Texas Christian University ,2005) is a professor of English and Texas Woman’s University, where he teaches graduate courses in history of rhetoric and feminist rhetorics and undergraduate courses in American studies and expository writing. A Lifetime Member of the Rhetoric Society of America, his articles have appeared in Rhetoric Review; RSQ: Rhetoric Society Quarterly; GLR: Gay and Lesbian Review; Literature and Belief, and elsewhere. In his work, he employs methods of feminist rhetorical historiography and rhetorical circulation to recover and animate discourses of the marginalized of the past.