Discovering a name and a slave narrative’s continuing truth

In a follow-up installment in 1839 to the anonymously authored Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave, the narrator testifies that a Charleston slave speculator known as “Major Ross” had sold his brother. The narrator notes that Ross lives in “a nice little white house, on the right hand side of King street as you go in from the country towards the market.”

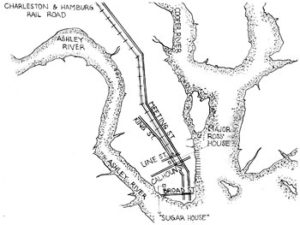

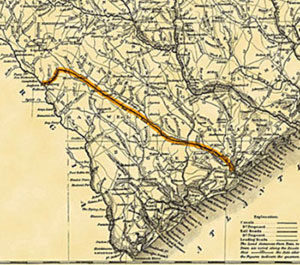

The right-hand side? Was that level of precision necessary? Because people challenged the veracity of slave narratives at the time they were published, details mattered very much. But the level of specificity in this instance caught my eye. The facts were borne out: property records in the Charleston County Register Mesne Conveyance Deeds office show that in 1831, a James L. Ross, known also as “Major Ross,” purchased a house situated on the west side of King Street, just a few blocks north of the market. If you were entering the city of Charleston from the country, Ross’ house would indeed have been on the right-hand side (fig 1).

And so it comes down to that. In order to prove his own humanity, the truth about the human capacity for cruelty, and the very reputation of abolitionist crusaders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, this survivor made his story unassailable by giving the correct location for the speculator’s house on King Street in Charleston.

Back in 2007 when I started to select and edit pieces for a collected volume of South Carolina slave narratives titled I Belong to South Carolina, I became interested in a little-known memoir titled “Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave.” I traced the source of the narrative back to the Advocate of Freedom, a small abolitionist newspaper from Maine, and wove this source discovery into the brief introduction to my book. After the collection was published in 2010, I moved on to other projects.

And yet the “Recollections” narrative continued to haunt me. The particular circumstances of its publication, sketched out below, coupled with its agonized detail struck me as so honest that I couldn’t let its author remain anonymous.

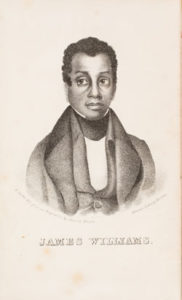

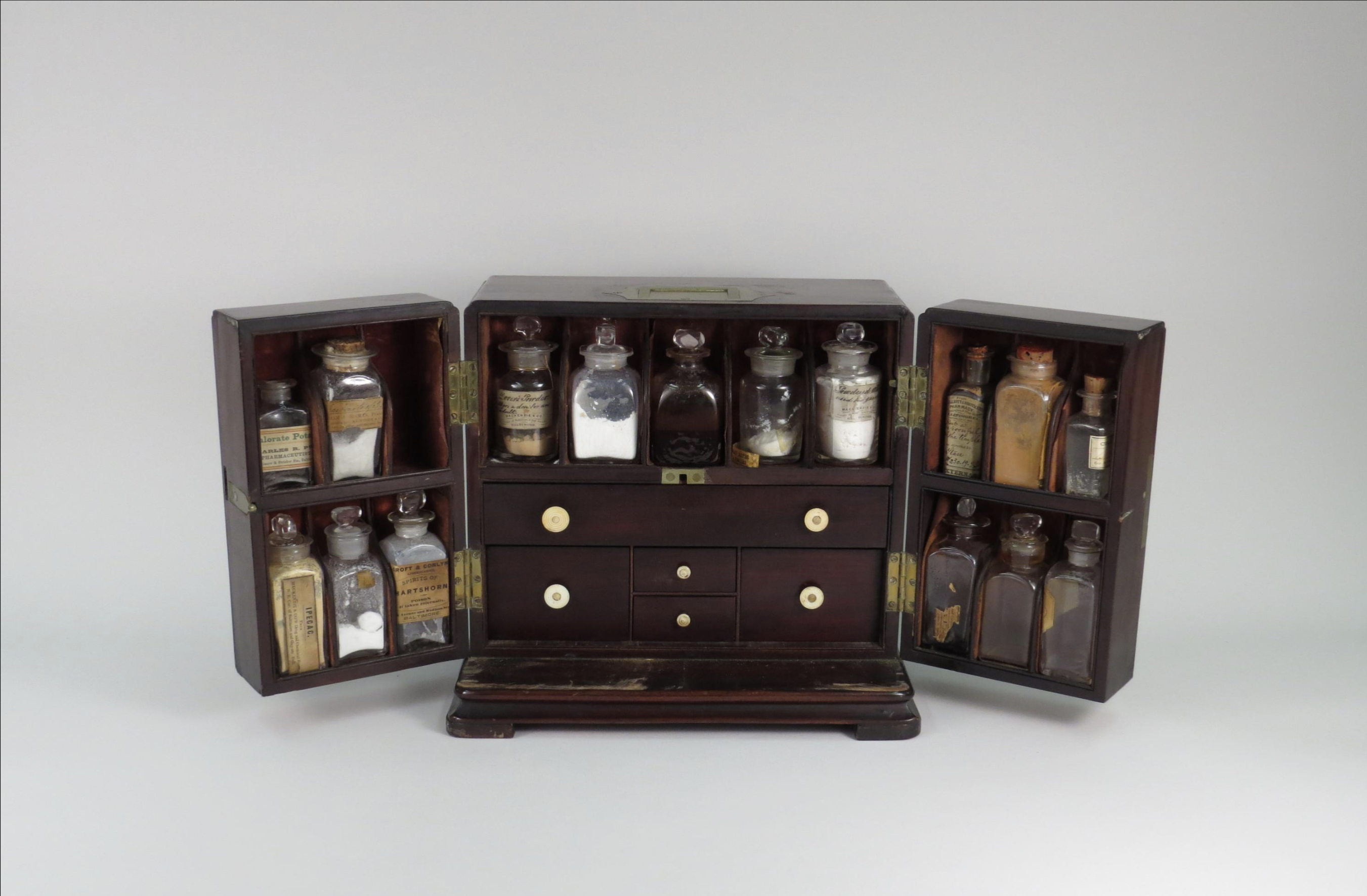

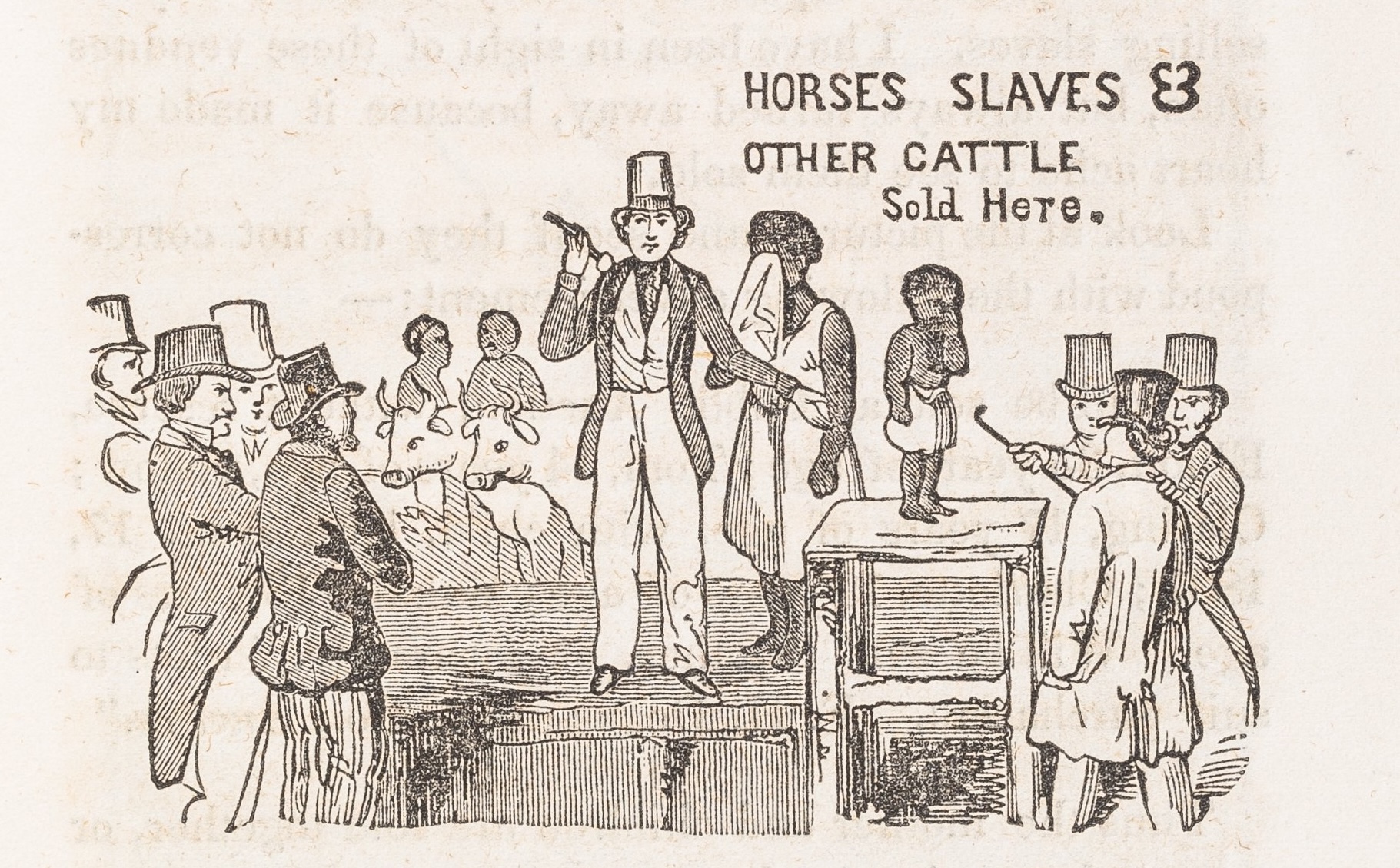

1838, the year in which “Recollections” appeared, was an especially difficult one for the anti-slavery movement. In the early months of that year, the American Anti-Slavery Society’s Executive Committee sponsored the publication of what they believed to be the first full-length book by an escaped slave, The Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave. The Committee members arranged for Williams to dictate his narrative under careful supervision in exchange for safe passage to England. They framed it with testimonials and an introduction by noted poet John Greenleaf Whittier. Convinced that its fiercely powerful testimony would galvanize a complacent America into action against human bondage, Executive Committee members mailed a copy to every member of Congress and vigorously promoted it through advertisements placed in periodicals across the nation (fig. 2).

And then, disaster struck. The narrative’s truthfulness was almost immediately, and persuasively, challenged. By late March 1838, a newspaper editor in Alabama publicly attacked its claims, and later the Anti-Slavery Society itself—after concerted and lengthy efforts—ruefully acknowledged that it could not authenticate the narrative. Details were inconsistent. Names and places cited by Williams did not clearly correspond to actual people and locations, and thus could not be verified to counter accusations of fakery. Most troubling of all, the Anti-Slavery Society’s efforts were stymied because James Williams had left for a destination unknown, and could not be found. On October 25, 1838, the Executive Committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society declared that the book would no longer be published, and directed the publishing agents to discontinue sale of the work. The incident eroded the credibility of the society and jeopardized the future of the anti-slavery movement.

(The superb work recently done by scholar Hank Trent to trace Williams’s controversial story reveals that the core of the Williams narrative was, indeed, true—but this work came over 170 years too late to help the Anti-Slavery Society.)

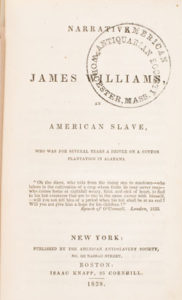

Despite the society’s shattered reputation in the fresh wake of the Narrative of James Williams scandal and the public’s resulting skepticism about the truthfulness of slave narratives in general, in the summer of 1838 the editors of the Advocate made the surprising decision to print yet another slave narrative, “Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave.” This story, I believed, carried with it a burden of truthfulness that no earlier (or later) narrative had ever faced. And yet the abolitionists decided to not only publish the piece, but also to conceal the name of the runaway. And so: Whose story was it?

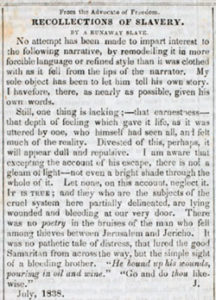

Its origins were a bit unclear. The first of five installments was published in the Advocate of Freedom on August 2, 1838, in Maine. The Emancipator, the official publication of the National Anti-Slavery Society based in New York, recognized the power of the narrative almost immediately and started to run the series as well, with the first installment appearing in their paper on August 23 (fig. 3). The original memoir seems to have been transcribed in Maine by a person known as “J” who was a close ally of the editorial team of the Advocate. Another person identified only as “A” sent J’s transcription to the Advocate. As an editorial note mentioned on the page preceding the first Advocate installment, the editors received the manuscript from “a source of the highest respectability.” They included an explanation provided by “A”:

Messrs Editors:— I enclose the “narrative of a runaway slave,” for which I request a place in your paper. It was taken from his lips by a gentleman of indisputable integrity and fairness, and with the greatest care and caution. The manuscript has been repeatedly read to the young man, and he was cautioned in every instance to state only the simple facts; and after the care that has been taken to correct any mistake or error, into which he may have been led, I believe the “recollections of a slave,” are entitled to the confidence of the reader… .”

According to the narrative, the narrator was born in South Carolina, outside of Charleston, in a rural area known as “Four Hole Swamp” (fig. 4). Owned first by “Widow Smith” and then her son, Alfred, he was hired out to many different men, all of them vicious in their own ways. Indeed, much of the narrative chronicles in harrowing detail the violence he saw. He speaks of abuse—and even murder—of women, children, and infants at the hands of his owners and their neighbors. His litany demonstrates clearly that such treatment was common practice and not simply the behavior of morally bankrupt outliers. On one occasion he visits a neighbor and testifies that:

I saw a man rolling another all over the yard in a barrel, something like a rice cask, through which he had driven shingle nails. It was made on purpose to roll slaves in. He was sitting on a block, laughing to hear the man’s cries. The one who was rolling wanted to stop, but he told him if he did’nt [sic] roll him well he would give him a hundred lashes.

After several years of being hired out to various subcontractors in the region, he was sold to David or “Davey” Cohen, the scion of one of the wealthiest Jewish families in the United States at that time. Finding the conditions there intolerable, he fled twice, but upon being recaptured the second time he was taken to the slave workhouse in Charleston. This site was known as the “Sugar House,” an old sugar warehouse repurposed into a prison and workhouse for slaves. It was notorious for the systematic torture that occurred there, and especially for the treadmill run by slave labor that not infrequently maimed and killed the weary people chained to its rotating pedals. There he was visited by David Cohen’s father, the wealthy and eminent Charlestonian Mordecai Cohen. Cohen Senior sent for his son, and then David Cohen himself arrived and ordered the narrator to receive fifty lashes. David Cohen then further directed the men of the Sugar House to whip the fugitive twice weekly between days on the treadmill (fig. 5).

After weeks of enduring abuse, the narrator was then sold to John Fogle, who soon thereafter hired him out to the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company (fig. 6). Our narrator found circumstances there even worse than at Fogle’s. He wrote, “After we were whipped we had to go straight back to our work. They did not care whether we got well or not, because we were other people’s niggers … I worked there about two months, digging pits and wheeling, and taking up old rails and laying new ones …”

Afraid the work and the whippings on the railroad would ultimately kill him, he escaped once again, this time hiding aboard a train bound for Charleston. Once in the city he found a sympathetic ship steward who smuggled him to Boston. He was taken ashore and directed to a boarding house for colored men. Weakened by the journey, he barely made it:

I went along holding on by the houses, and when I had got down the street a good ways, I met a colored man and asked him where the boarding house was. He asked me if I was a sailor, I told him not much of one, but that I had just come from a ship. He said “I understand it all.” He knew from my dress and the cotton on my head and clothes, that I was a runaway. He carried me to a boarding house, and the next day to ——, who gave me some warm clothes. He sent me into the country to stay with some colored people.

The fugitive narrator doesn’t explain precisely how, by the spring of 1838, he made it from Boston to Maine, but presumably he was smuggled north to safety and found harbor with the anti-slavery activists who took down his story.

And Maine is where I found myself this past spring, doing research about an entirely different fugitive, when I was prompted once again to think about “Recollections.” I had hit a lull in my work at the Maine Historical Society in Portland, and I thought to request the entire run of the Advocate of Freedom to see if I could find any clues about the narrative by looking at the newspaper it ran in to see it afresh. The series was such a harrowing read that I thought perhaps published letters to the editor might debate it. Or perhaps there would be more information in the mission statement of the original issues that might give me more details about the process of or context for the narrative’s construction and publication. For hours I pored through issues, using a magnifying glass to read the Advocate’s small print on its large pages, unsure of what precisely might be there.

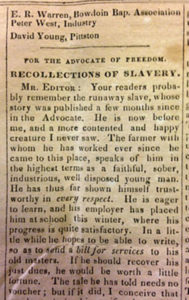

As is often the case with primary source research directed by instinct, not evidence, I stumbled upon something entirely unanticipated. In an issue dated February 21, 1839, I found an article following up on “Recollections” some three months after the original serialized narrative was published (and which was never reprinted in The Emancipator as far as I can tell). The piece was brief, but appeared to have served multiple purposes: it provided yet more testimony to the evils of slavery, and it also bolstered the credibility of the narrator and the reliability of the editorial team that backed his story (fig. 7).

The sequel ran about a year after the narrator likely arrived in Boston, and was framed by an introduction that opened as follows:

Mr. Editor: Your readers probably remember the runaway slave, whose story was published a few months since in the Advocate. He is now before me, and a more contented and happy creature I never saw. The farmer with whom he has worked ever since he came to this place, speaks of him in the highest terms as a faithful, sober, industrious, well disposed young man. He has thus far shown himself trustworthy in every respect. He is eager to learn, and his employer has placed him at school this winter, where his progress is quite satisfactory. In a little while he hopes to be able to write, so as to send a bill for services to his old masters. If he should recover his just dues, he would be worth a little fortune.

The piece continued by adding a new recollection: that of how the young man had watched in pain as his brother was marched off by speculators in Charleston. While the original narrative had in part described the inhuman conditions of the Sugar House, this sequel added yet more poignant details about how others in the community of outcasts understood the plight of the inmates. The narrator explains:

They [Speculators] kept all the slaves in the Sugar House, only sometimes when the Sugar House was full; then they put some in the Jail. The Jail is right along side of the Sugar House: —there is only a wall between them. The Crazy House and the Poor House are both close by. Sometimes the people in the Poor House would throw scraps out of the window into the Sugar House yard, and every morning when we were let out, we used to rush up to the wall to get what had been thrown out over night. —I never eat the meat, it was so dirty—but sometimes got a scrap of bread.

The brief sequel featured a quick sketch of how speculators worked and what those practices meant for the brothers who were to be forever separated by them. The sketch also demonstrated further intimate knowledge of the city of Charleston. Having discovered this brief yet powerful sequel (presented in its entirety below for the first time since its original publication in 1839), I became determined to find the author’s identity and share this previously unknown work.

Many details—especially about slave owners and established residents of Charleston—from both the original narrative and its sequel have been easy to verify. I’ve identified in census and property records many of the people he names, occasionally with small variants in spelling. (An Elizabeth Smyth bought property on Four Hole Swamp in 1804, for example, and it seems likely she was the “Widow Smith” Jim refers to as his first owner. Elias Rudd bought Four Hole Swamp property in 1814, and surely was the neighbor “Elias Road” referenced in the original narrative.) Other names mentioned correspond directly to those appearing in historical records: David and Mordecai Cohen, for example, were well-known figures in Charleston. “Bellinger,” the man who tortured slaves by rolling them in nail-pierced barrels, was in all likelihood William Cotesworth Bellinger Jr. (1788-1828), who lived near Dorchester Road in Colleton County, as Jim described. Many other names and places mentioned by Jim appear elsewhere in historical records.

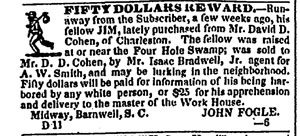

But where and how to find the narrator, who was not only an escaped slave but an author with no name? The easiest tack, I figured, was to start with runaway slave advertisements.

After searching fruitlessly through issues of The Charleston Mercurybetween July 1837 and June 1838, I turned to the Charleston Courier. Quite quickly I found an advertisement for a fugitive in mid-December of 1837 placed by a “John Fogle.” The details concur with everything in the narrative. Helpfully, the ad even listed the chain of previous owners, corresponding precisely with how the anonymous narrator of “Recollections” described them. And Fogle had given the fugitive a name: Jim (fig. 8).

FIFTY DOLLARS REWARD—Runaway from the Subscriber, a few weeks ago, his fellow Jim, lately purchased from Mr. David. D. Cohen, of Charleston. The fellow was raised at or near the Four Hole Swamp; was sold to Mr. D. D. Cohen, by Mr. Isaac Bradwell, Jr. agent for A. W. Smith, and may be lurking in the neighborhood. Fifty dollars will be paid for information of his being harbored by any white person, or $25 for his apprehension and delivery to the master of the Work House.

Midway, Barnwell, S. C.

John Fogle

I’m not naming Jim here, for he had a name. But I like to think that I’ve re-assembled or even re-collected some of the scattered fragments of his world. Pressured by an immense burden of truth, Jim shaped his story as directly and honestly as he knew how. His tale was doubtless shaped and perhaps even manipulated by its editors, but Jim’s voice emerges nonetheless as a piercing testament not only to the cruelty of slavery, but as an assertion of his own manhood, his own honor, and his willingness to claim his humanity.

He placed a speculator’s house on the right-hand side of King Street, and with that petty detail shamed the very premise of fact checking. Thus it is with some irony that I hope my project to trace the mundane details of his life nonetheless honors the greater story he tells.

Coda

What happened to Jim after his addendum was published? Two of my student assistants and I came up with at least one plausible future for Jim.

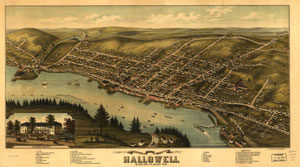

The federal censuses from 1850, 1860, and 1880 record James Matthews, a man of color living in Maine who listed his parents as being from South Carolina and who was possibly born around 1807: this person was most likely Jim. Significantly, Matthews doesn’t appear in any Maine records before 1850, and when he does show up, it seems that he is a middle-aged laborer taken in by the “City Poor Farm” of Hallowell, Maine—the very town where the Advocate of Freedom was published (figs. 9 and 10). The city was known for its many abolitionist activists during this era (the first abolitionist society in Maine, the Hallowell Anti-Slavery Society, was founded there in 1833), and so we can suppose it was a congenial place for a man seeking community and protection. Indeed, one Hallowell citizen, the Reverend Joseph C. Lovejoy, is quite likely “J,” the man who first transcribed Jim’s story. Lovejoy, a close associate of the Advocate’s editors, published an 1838 memoir of his brother, the famous abolitionist printer Elijah Lovejoy who was assassinated by a pro-slavery mob in Illinois in 1837. Moreover, Rev. Lovejoy went on to transcribe the life narrative of Lewis P. Clarke, another fugitive slave, in 1845. It thus seems quite possible that he would have been involved in bringing Jim’s story to light in 1838. If nothing else, he knew the power of print for a political cause.

Sadly, while Matthews is listed as a laborer and pauper who lived in Maine until his death in 1886, it seems he suffered from some sort of mental illness. Records consistently describe him throughout the decades as “insane,” and the 1850 census indicates that he was getting treatment at a facility known as the Maine Insane Hospital in nearby Augusta.

Neither Jim’s narrative nor the introductory comments written about him indicate he was anything but a resourceful and intelligent young man, albeit one who had, like innumerable other slaves, suffered terribly. And slavery left its physical as well as emotional scars on the man: the Advocate’seditors interrupt his narrative at one point to attest that “Some of the scars [on his back] are the size of a man’s thumb, and appear as if pieces of flesh had been gouged out, and some are ridges or elevations of the flesh and skin. They could easily be felt through his clothing.” It would not be surprising if he were to suffer in later years perhaps in part because of the abuse he suffered as a younger man.

In the Hallowell Cemetery there stands a grave marker for James Matthews. It is a handsome stone, an honorific that might be surprising for a black, mentally ill pauper who was far from any family. But Hallowell was a special place. Matthews was part of the community, and the city records note that he died of “Old Age” at the age of 79 years. He was accorded a proper granite gravestone, made, I presume, from the rock harvested from the quarries Hallowell was famous for. The inscription reads: “He hath done what he could” (fig. 11).

I therefore conclude, albeit with respectful trepidation, that the man, James Matthews, who was buried in Hallowell, was Jim, the narrator of Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave and its sequel. It seems likely he lived out his days in Hallowell, Maine—ill but cared for in a small community and managing to do what he was known for: enduring.

Special thanks to Collin Eichhorn and Kristin Buhrow, who assisted with the research for this essay. Sam Weber of Hallowell assisted me greatly with information, illustrations, and city records from Maine. Thanks also to Clemson University’s Department of English for sabbatical release support; the Clemson University College of Arts, Architecture & Humanities, which provided me with travel funds, and the Maine Historical Society reference staff for their patient consultations.

Further Reading

The complete run of the Advocate of Freedom (published variously in Brunswick, Augusta, and Hallowell, Maine, from 1838 to 1841) can be found in all of its large format glory (the pages are huge and the font is small) at the Maine Historical Society Research Library in Portland, Maine. If you wish to read it online and have access to a library with a subscription, it has been digitized by Gale/Cengage Learning and is available in their Slavery & Antislavery: a Transnational Archive collection.

My version of the “Recollections of Slavery” narrative was included as a then-anonymously authored narrative in Susanna Ashton and Robyn E. Adams, et al., eds., “I Belong to South Carolina”: South Carolina Slave Narratives (Columbia, S.C., 2010). The most recent publication of James Williams’ narrative is edited by Hank Trent, who does a superb job of untangling the fraught story of Williams’ life and documenting how the burden of abolitionist truth-telling necessarily reshaped the narrative and ultimately doomed its reception. See Hank Trent, ed., Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave. Annotated edition (Baton Rouge, La., 2013).

The Text of the Sequel

Advocate of Freedom

Brunswick, Maine, Thursday, February 21, 1839

For the Advocate of Freedom

Recollections of Slavery.

Mr. Editor: Your readers probably remember the runaway slave, whose story was published a few months since in the Advocate. He is now before me, and a more contented and happy creature I never saw. The farmer with whom he has worked ever since he came to this place, speaks of him in the highest terms as a faithful, sober, industrious, well disposed young man. He has thus far shown himself trustworthy in every respect. He is eager to learn, and his employer has placed him at school this winter, where his progress is quite satisfactory. In a little while he hopes to be able to write, so as to send a bill for services to his old masters. If he should recover his just dues, he would be worth a little fortune. The tale he has told needs no voucher; but if it did, I conceive that we have it in his uniformly upright conduct, and the consistent manner in which he always relates it. Those who have seen him most, and heard his story oftenest are convinced beyond a doubt that he has told the truth.

I send you in his own language, an account which he has just given me, of his separation from his oldest brother. It was told with evident emotion, and it does not need comment or embellishment to send it home to any “heart of flesh.” Let each one make the case his own, or look at it in the light of the gospel, and its enormity will be apparent. Yet incidents like this are of so frequent occurrence at the South, that wicked as they are, even Christians are not affected by them, but treat them with unconcern, just as the entire slave system is treated by some religious bodies at the North.

J.

_____________

About five years ago, when I lived with Isaac Bradwell, my brother was sold to go to New Orleans. Major Ross sold him—Ross lives in Charleston, a nice little white house, on the right hand side of King street as you go in from the country towards the market. He was a speculator and bought my brother and a great many others, to make money by selling them. One day I and another man went to Charleston with a load of cotton. While we stood on Boundary street, watering our horses, we saw two gangs of speculator’s niggers driven down Boundary Street at Godson’s wharf. The first gang belonged to Hugh McDaniels and his brother. It must have had in it as many as two or three hundred men and women, chained together by the neck and hands, and a great many little children, running along by the side with bundles, and eight or ten drays with baggage, following behind. Ross’ gang was about one half as long. My brother was in the last drove. Just as he got along side of us we saw him, and then we were so glad—we all said “how d’ye,” and “good bye,” and he told Aaron to tell sister “good bye” when he got home.—We could not say much, because they passed right along. Some of them did not care much about it; some looked sad; and some of the women were crying, and men too. When my brother said good bye, he cried. The drove was a good while in passing, and after it got by, Aaron ran down to the wharf to see my brother again. When he came back he told me that if I made haste I could see him before he went on board the ship. Then I ran down, but they were all driven into the ship yard, and the gate was fastened. I got up and looked over the paling, and after a while I saw him. He hung his head down, and looked like he was fretting a good deal. Major Ross was there, and my brother begged him—”please Mr Ross, don’t ship me off”—but Mr. Ross did’nt say anything; only walked about and laughed. When my brother saw me he nodded his head to me, and then I went away. That was the last time I saw him. I did not stop till he was shipped, because I was afraid the constable would take me.

The McDaniels are speculators. One of them is the largest man I ever saw. They kept all the slaves in the Sugar House, only sometimes when the Sugar House was full; then they put some in the Jail. The Jail is right along side of the Sugar House:—there is only a wall between them. The Crazy House and the Poor House are both close by. Sometimes the people in the Poor House would throw scraps out of the window into the Sugar House yard, and every morning when we were let out, we used to rush up to the wall to get what had been thrown out over night.—I never eat the meat, it was so dirty—but sometimes got a scrap of bread.

The McDaniels have been speculators ever since I can remember, but I recollect when Major Ross was’nt hardly anything at all. He used to be a bully for fighting. He kept a shop a good many years ago on “four holes,” and then he was fighting all the time. They called him “Bully Ross.” Black people carried things to him to sell. He used to tell them to fetch any thing they could get and he would buy it. So they were stealing and selling all the time. They went to him at midnight with cotton and corn and other things, and got salt fish and meat and tobacco, and the women got handkerchiefs; but he never gave us any money.—In this way he made a good deal of money, and then he bought niggers and hired them on to the rail road, and after a while he became a great speculator. He now owns a plantation at four holes, and is a very rich man. They say, about there, that Bully Ross has turned out to be quite a gentleman. When we carried him things to sell at night, he was always pleasant and coaxing us up, but now he owns slaves he treats them just as bad as any of them.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.1 (Fall, 2014).

Susanna Ashton is professor of English at Clemson University in South Carolina. She is working on a biography of a fugitive slave and abolitionist lecturer to be titled, A Plausible Man: The Life of John Andrew Jackson. She tweets on abolition and the study of enslaved people’s lives as @ashtonsusanna.