I write this the morning after Dylann Storm Roof, a resident of my home city, Columbia, South Carolina, was identified as the probable killer of Rev. Clementa Pinckney and eight members of Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, S.C., in an apparent crime of racial hatred. Rev. Pinckney attended the Nat Fuller Feast in Charleston on April 19, 2015.

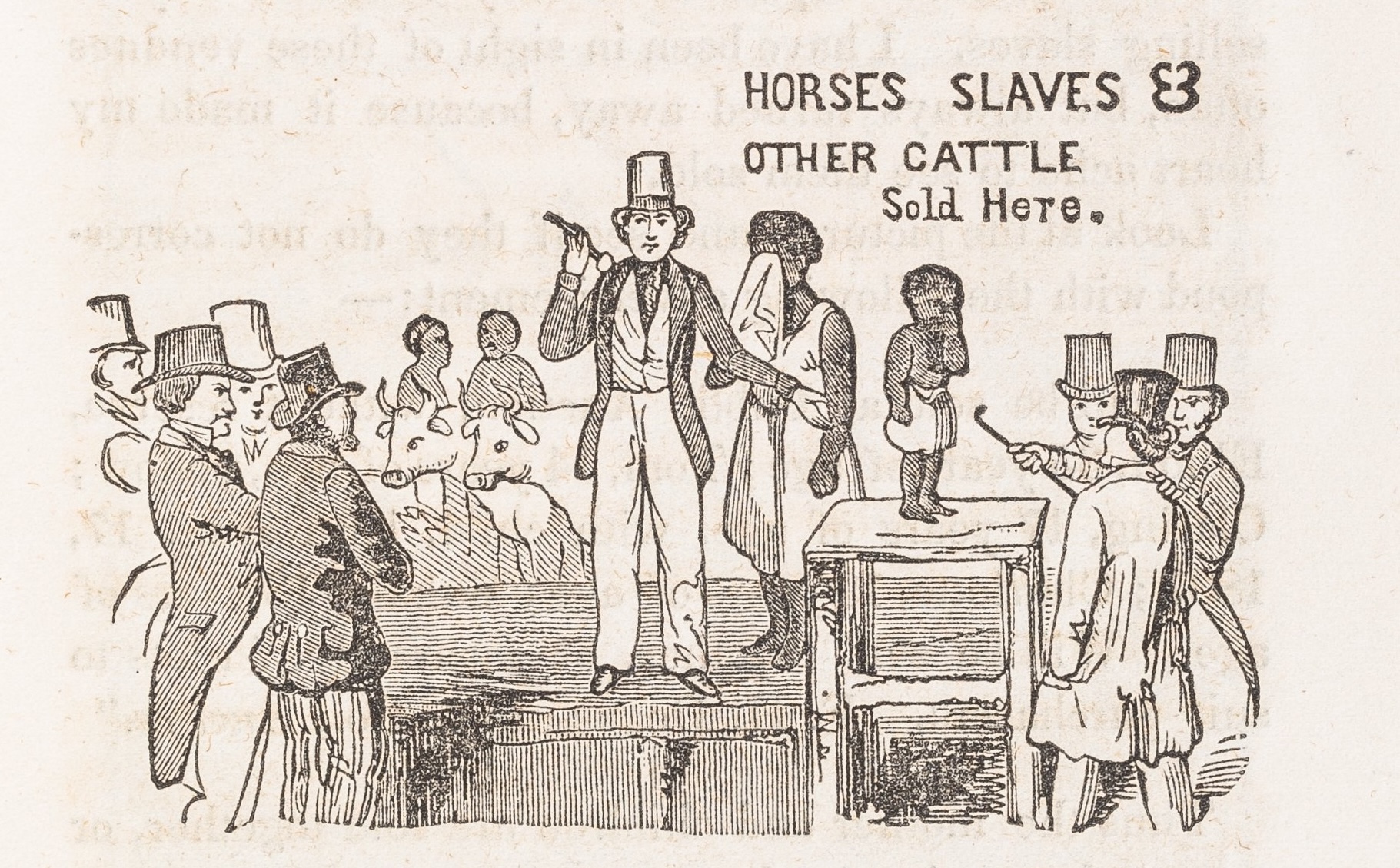

Racial hatred depends on a belief in certain representations of an entire moiety of people. The images and narratives that elicit hatred depend on the distance that media interposes between person and person, between audience and represented. Anything that closes the distance, that eliminates the interpositions of media to make connection personal between people, has the potential to lessen hatred. Bringing people who were strangers of different racial and cultural backgrounds together at a common table has the power to lessen suspicion and enmity. This was Nat Fuller’s insight. It was also the hope of those who organized Nat Fuller’s Feast. I did not know Chef Kevin Mitchell or Chef B. J. Dennis before they agreed to assist in this effort. Now they are my friends and allies. I had never spoken to Rev. Pinckney before meeting him on the evening of April 19. I found him a remarkable man.

Whatever fosters face-to-face contact and conversation; whatever enables pleasure to be shared by people; whatever regularizes the sociability and civility of people living in a vicinity works to the good. I lived in Charleston for twenty years—from 1983 to 2003—and during that time took comfort in two spaces where people of different classes, ages and ethnicities met and engaged in common pursuits: the Japan Karate Institute dojo and the Charleston Public Library. In both places there was an orderly protocol known and observed by everyone, a clear and shared aspiration for self-improvement by everyone present, and an object of desire (karate skill in one, the entertainment and knowledge contained in books in the other).

Feasts, too, have protocols, shared moods, and objects of desires. Nat Fuller knew that. There must be a stable framework in which such conversations and contacts can thrive. And feasts can be repeated—made into anniversary celebrations that promote solidarity. I remember thirty years ago reading a Puritan commentary on the Book of Esther and the institution of the Feast of Purim among the Jews. I remembered particularly the observation that the Feast of Purim has endured among the people, while the Chronicles of the Persian Empire, which are alluded to repeatedly in Esther, have vanished. Nowadays when social media saturates our sense of time and place, and images of ever-increasing provocativeness are broadcast in a bid to catch our attention, it is good to recall that direct social interaction can be instituted for the long-term betterment of people and has a power to outlive the blizzard of representations.

Chef Mitchell spoke a truth in his invocation at Nat Fuller’s Feast when he reminded us of the old custom that those who shared a meal together—who took bread and salt—are now bound to the obligations of familiarity: we can no longer treat our fellow guests with indifference, can no longer harm them, but are obliged to aid and protect.

Rev. Clementa Pinckney, like Nat Fuller, was a man who encouraged people to come to know one another better and to share the best things of life. As we remembered Nat Fuller in our commemoration on April 19, in future feasts we will also remember Clementa Pinckney, a latter-day adherent to Fuller’s vision of common wellbeing as well as disciple of Jesus Christ.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.4 (Summer, 2015).

David S. Shields is the Carolina Distinguished Professor at the University of South Carolina and the chair of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation. He publishes monographs in the fields of early American literature and culture, the history of photography, and food studies. His photographic history Still: American Silent Motion Picture Photography won the Ray and Pat Browe Award for “Best Single Work in American Popular Culture” for 2013 from the American Culture Association-American Culture Association. His culinary history Southern Provisions: The Creation and Revival of a Cuisine was published by University of Chicago Press in March 2015.