Marine hospitals in the early republic

In the introduction to the Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne offers a snapshot of the old Salem customhouse. “Here, before his own wife has greeted him,” writes Hawthorne, was the “sea-flushed ship-master, just in port, with his vessel’s papers under his arm in a tarnished box.” Nearby, too, was the anxious merchant, about to learn the fate of “his scheme.” Fresh from the countinghouse, “the smart young clerk, who gets a taste of traffic as a wolf-cub does of blood,” hovered about. “Cluster all these individuals together,” concludes Hawthorne, and “it made the Custom-House a stirring scene.”

Also nearby was the merchant mariner—a crucial laborer in an early American economy that was deeply dependent on foreign commerce. Sailors helped carry American produce to European, Caribbean, and Asian markets. They also brought foreign goods back home to the United States. But seafaring was extremely dangerous work. Storms and plagues frequently struck Atlantic waterways. Falling crates and crashing barrels caused great harm to life and limb. Indeed as Hawthorne observed, these working conditions often left returning sailors “pale and feeble.”

In Salem, and elsewhere in the young United States, merchant mariners thus appeared at the customhouse in search of “a passport to the hospital.” In 1799 the federal government established these hospitals, or marine hospitals, in most ports throughout the country to care for sick and disabled merchant mariners. The government financed the hospitals by a tax on sailors’ monthly wages. As ships returned to port, customs officials collected the marine hospital tax and forwarded it to the federal Treasury Department in Washington, D.C. The Treasury then distributed these funds to customs officials to hire doctors and nurses to care for merchant mariners. In larger ports, such as Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, and New Orleans, the federal government operated its own hospitals. Throughout the nineteenth century the marine hospitals grew westward with the nation. By 1900 the hospitals had treated hundreds of thousands of merchant mariners.

That the federal government created this health care system for merchant mariners in the early American republic will surprise many. This is due in no small measure to the tenor of political debate about health care in American society. Advocates of government structured, universal health care plans claim that the times are too fast and costs too high to return to the old days of “pay-as-you-go” care. Deregulationists counter that only by removing the stamp of government from health care can society relive the great success of decades and centuries past. Both sides presuppose that government regulation and provision of health care is a new development. But the story of the marine hospitals in the early American republic suggests that the United States has a long history of using institutions to manage public health. Through the marine hospitals, the federal government used health care to regulate a crucial labor force in an age of maritime commerce. Treating sick and disabled merchant mariners helped stabilize the maritime labor force. More broadly, through the marine hospitals, we witness the actual points of interaction between government, community, and individuals. A glimpse within hospital walls reveals the rich, diverse personal experiences of working in, or being treated in, an early federal marine hospital. To be sure the marine hospitals were effective instruments of politics and policy. But within the marine hospitals, medical practice and administration was far more than an abstract tool of political economy. Rather, the stories of sickness, injury, admission, treatment, resistance, and regulation that characterized life within the marine hospitals reveal how the federal government shaped the social, economic, and political order of the early republic to a degree scholars have only just now begun to appreciate.

The Rise of the Marine Hospitals

The United States’ approach to health care for maritime laborers built upon British and colonial antecedents. Since Elizabethan times, Great Britain supported hospitals—the “Chatham Chest” and Greenwich Hospital—by taxing naval and merchant mariners’ monthly wages. In 1710, Virginia imposed a small tax on tobacco exports to England to fund a hospital for mariners at Hampton, Virginia. Nineteen years later Parliament ordered Pennsylvania to tax seamen’s wages for a marine hospital in Philadelphia. In 1749 Charleston, South Carolina, ordered churchwardens to create a hospital for sick and disabled sailors. Finally, voluntary “marine associations” in Boston (1742) and New York (1769) also cared for ailing sailors.

Why did Anglo-American society lavish such attention on health care for the merchant marine? First, mercantilist economic theory emphasized the importance of a healthy maritime labor force. In mercantilism, economic dominion was the extension of war by commercial means. Countries vied with one another for control of the most markets, over the broadest expanse of land. Mariners were the foot soldiers in this race for global power. But governments also regulated maritime health for moral reasons. In Anglo-American society, mariners were partially free and partially unfree laborers. It was believed that the mariner had volition enough to choose his course and negotiate for wages. But it was also believed that the mariner lacked sufficient sense to care for his own wellbeing. From this sentiment arose the infamous stereotype of “Jack Tar” as a coarse, hard-drinking character who purposefully exposed his own body to great harm. If Jack Tar failed to care for himself and if commerce and society so depended on Jack Tar, was it not society’s responsibility—and was it not in society’s best interest—to preserve and protect the mariner for his own good and for the public good? As Maine Senator F. O. J. Smith put it in 1838, “both the Government and the merchant” had “almost the same abiding interest with the sailor himself, in a matter upon which so much depends for a requisite supply of healthy and able-bodied seamen.”

This concern for the health of merchant mariners loomed large in postcolonial America. During the American Revolution, some dreamed of a self-sufficient economy that would not rely upon distant and often politically problematic European markets. But during the 1790s such utopianism gave way to a hard, and ultimately lucrative, reality: the United States economy remained tethered to European markets and long-distance maritime trade. Great profits awaited American merchants who did business in England, France, and the colonial ports of the West Indies. Now again society realized the great significance of the merchant marine. Commentators of every political stripe—editors such as John Fenno, political economists such as Pelatiah Webster, and physicians such as Benjamin Rush and Samuel Latham Mitchill—found common ground in their advocacy of a system of marine hospitals. Importantly, the United States Constitution mandated a uniform, national system. Dr. Mitchill, soon to be elected to Congress, made this clear in a 1799 petition to Congress. Since “the regulation of commerce belong[s] exclusively to the National Legislature,” only Congress and the federal government could handle the problem of maritime labor that had once fallen to the individual colonies.

In 1798, Congress thus enacted a law “for the relief of sick and disabled seamen.” The bill taxed mariners’ wages—at the rate of twenty cents per month—to finance health care for ailing sailors in ports throughout the country. The gentlemen attorneys and merchants who wrote this legislation did not trust mariners to personally pay hospital taxes. Rather ship captains garnished the wages and paid them directly to federal customs officials. In this sense the marine hospital tax was a progenitor of the payroll tax. But this method of taxation also conveniently fit the maritime master-servant relationship in the early republic. As maritime historian Marcus Rediker illustrates, the merchant vessel was a highly disciplined space in which sea captains exerted immense authority over the mariner’s body and labor. Captains and merchants also enjoyed advantages in the bargaining of labor contracts, which were typically informal and unwritten. These power relations even influenced the disbursement of wages. To prevent desertion, full payment came only at the conclusion of a voyage. The marine hospital tax now functioned on the same principle and power structure. The merchants and sea captains, who controlled the mariners’ labor and wages, now ensured that mariners would pay the taxes necessary to maintain a healthy and productive labor force.

The federal customhouses efficiently collected the marine hospital tax. Rough estimates suggest that from 1800 to 1812, mariners’ wages fluctuated from fifteen to twenty dollars per month. Marine hospital taxes constituted a withholding of between 1 and 1.33 percent per month. In these years, tax collection peaked in 1809 at $74,192, the majority of which came from New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston—a trend that would continue throughout most of the century. On the strength of the marine hospital tax, the federal government established a network of hospitals and other health care facilities for the merchant marine.

As a matter of policy, the marine hospitals treated several thousand mariners per year, and in so doing, helped to maintain a stable supply of healthy maritime workers. This was a goal that Alexander Hamilton had articulated in Federalist no. 11. “When time shall have more nearly assimilated the principles of navigation,” wrote Hamilton, “a nursery of seamen…will become a universal resource.” This “nursery of seamen” indeed powered the United States economic expansion. Moreover, over time, the marine hospitals’ function as a medical safety net for mariners was understood to serve as an incentive, as Senator F. O. J. Smith opined in 1838, “to induce a certain portion of its citizens” to become seamen despite “risks of health, and of life itself, far beyond what are incident to any other class of pursuits.”

One measure of the importance of the marine hospitals to the American economy was the great demand for new hospitals in emerging markets. In 1802 Natchez, Mississippi, a growing entrepôt that connected the plantation trades with the Northwest and Gulf Coast, petitioned Congress for a marine hospital to care for sailors who “fall victims to climate and disease.” Two years later the Mississippi Territorial Legislature reiterated that since “the whole commerce of the Western Country is brought to that place,” the “aid of the general government” was required to construct a hospital at Natchez. In 1807 Thomas Jefferson’s son-in-law took up the lobbying effort. Only a marine hospital could preserve the “many lives of valuable laboring citizens.” In New Orleans the federal government created a marine hospital before the United States officially assumed control of the Louisiana Purchase. President Thomas Jefferson raised the issue during his annual message to Congress in February 1802. Two months later, Congress directed customs officials in nearby Fort Adams to tax mariners’ wages to support the lease of ward space from the Crescent City’s municipal Charity Hospital. Supervising the hospital would be Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, Dr. William Bache. In 1803 the New Orleans Marine Hospital treated over four hundred American sailors. Although fire destroyed the Charity Hospital in 1808, marine hospital patients and others continued to receive treatment in City Hall until the construction of a new facility in 1815.

Life Inside the Hospital Walls

On April 4, 1808, a twenty-five-year-old merchant mariner arrived in the port of Baltimore after a long voyage from the Netherlands. The Baltimore Medical and Physical Recorder referred to this sailor only as “LD,” to preserve his anonymity, but believed that the sailor suffered from some sort of fever. His temperature had fluctuated over the course of a long and arduous voyage. His abdomen “was swelled to twice its natural size, and the thighs and legs also considerably enlarged.” Across his entire body appeared “a yellow bilious aspect.” Five days later “BH” appeared, origins unknown, sporting “large swelling” throughout his body and “numerous small ulcers scattered over his whole body.” His was clearly a case of syphilis. BH himself had admitted “the infection had been received…about twelve months before, during all which time he had been at sea.” Both patients would receive treatment at the Baltimore Marine Hospital.

For mariners such as LD and BH, the path to a hospital bed began at the customhouse. As these sailors disembarked from their vessels, they faced examination by customs officials to determine eligibility for the marine hospital. Customs officials first decided whether or not the petitioner was truly a member of the merchant marine. Generally, as was policy at the Boston customhouse, the collector required “a certificate from the captain they sailed with or the owner” attesting to the sailor’s service. These were by no means formal documents. Most often these “certificates” were scraps of paper adorned with hasty scrawl. Next the collector ensured that the mariner had contributed his fair share of hospital taxes. Each customhouse maintained a large ledger with these hospital tax records. Sick or disabled mariners who passed both of these tests received a chit recommending entry into the marine hospital. These informal certificates bore the signature of the highest-ranking customs official at the port.

With a customhouse certificate in hand, the mariner now made his way to the marine hospital. In smaller ports, there was no “hospital” to speak of, as the customs collector contracted local physicians to care for mariners who were boarded in a single room in a private residence. In such a case the resident of the house took informal care of the mariner, while the physician stopped in periodically—usually daily—to monitor the patient’s progress. In Providence, for example, a local physician, Dr. Levi Wheaton, paid small amounts to local residents, including women, to house sick sailors. Repeat appearances in the marine hospital records suggest that many of these women may have depended upon the marine hospital payments—which occasionally exceeded $120 per quarter—for their income.

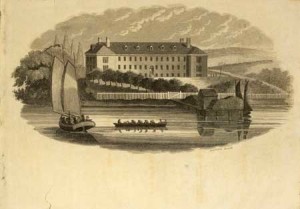

More is known about the larger facilities, especially the first marine hospital in Boston. From the customhouse at the end of the city wharf in Boston harbor (presently home to the New England Aquarium), the mariner made his way across the Charles River Bridge to Charlestown, where a two-story structure, one hundred feet long by forty feet wide, awaited. At the door the mariner would hand over his customhouse pass to the hospital steward, who monitored the patients around the clock. Now the mariner entered the marine hospital.

Medical treatment within these federal institutions was archaic by modern standards. “Nitrate of potash,” or potassium nitrate, was frequently fed to patients as a healing tonic. Sulfur, nitric acid, and ammonia were also used unsparingly. Mercury was a common treatment for rashes and bruises associated with venereal diseases. Through a process known as “salivation by Mercury,” physicians rubbed mercury into mariners’ mouths. This practice eventually fell into disuse, according to a Baltimore physician, because it caused “offensive symptoms,” including excessive saliva production, “soreness” of mouths, the loosening of teeth. But the marine hospitals did provide succor to some patients. Delirium tremens, a syndrome of uncontrollable convulsion and mental delusion caused by alcoholism, was swiftly treated through the liberal “use of sulphuric ether,” testified Boston Marine Hospital physician Charles Stedman in 1851. Marine hospitals also doled out laudanum, an opium derivative, to manage pain.

The marine hospitals proved useful to the rising medical profession in the early republic. Many medical schools permitted medical students to witness procedures, or intern, at the marine hospitals. The marine hospitals also served as venues for medical events. Pioneer physician Daniel Drake, for instance, inaugurated an important lecture series at the “New Clinical Amphitheatre of the Louisville marine hospital” in 1840. The marine hospitals even had the occasional innovation. In 1844, Dr. John Gorrie invented artificial refrigeration and a form of air conditioning as a treatment for malaria and other “fevers” in the Apalachicola Marine Hospital. Gorrie quickly recognized the potential of his discovery. “We know of no want of mankind more urgent than the cheap means of producing an abundance of artificial cold,” reported Gorrie in the Apalachicola Commercial Advertiser.

But there was more to life within these hospitals than the practice of medicine. Inside the marine hospitals, the interaction between government administration, local regulation, and individual volition influenced the functionality of these federal institutions. In the hospitals sailors found an atmosphere that contrasted sharply with their difficult life at sea. Rooms were small and quarters were cramped, to be sure. But an 1866 inventory of the Galena Marine Hospital suggests that mariners enjoyed straw beds adorned with hair pillows, cotton sheets, and wool blankets. The marine hospitals also had full service kitchens, although in New York, the quality of food was a frequent cause of complaint. “We will soon all be rotton [sic],” wrote nurse James Duffe, “for our butter is rotton and stinks worse than a skunk.” The food was not the only malodorous stench in the air. “The only constant condition accompanying the residence of a patient under this roof,” lamented Boston Marine Hospital physician Charles Stedman, “is that of being enveloped in the fumes of tobacco.” “From the smoke of tobacco, certainly, the house is never free,” concluded Stedman.

Smoking was hardly the only point of contention between hospital staff and patients. Conflict was a daily reality within the marine hospitals, as staff enforced rules that aimed to hasten convalescence but that curtailed the mariners’ customary behavior. Class may have had something to do with this. Marine hospital physicians lived in a different world from the merchant marine. For instance, Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse, a Boston Marine Hospital physician, was born into a middling Quaker family in Rhode Island. Yet he learned medicine in Edinburgh and Leiden. He was a roommate of John Adams and a correspondent of Thomas Jefferson. When Waterhouse returned to the United States in 1783 he received an appointment as Professor of the Theory and Practice of Physic at Harvard University.

Benjamin Waterhouse’s marine hospital was a disciplined environment. At the crack of dawn the hospital staff supervised and helped sailors bathe and clean their rooms. Patients were shaved twice a week. Apparel was changed every Sunday. Waterhouse also promised expulsion for mariners committing certain forbidden behaviors: spitting, writing on walls, thieving, absconding to the city, playing cards “or any other game of hazard,” and engaging in “all games of amusement.” In short, the rule of the marine hospital was “strict obedience.” For Waterhouse, it was vital that the mariner, quite literally, change his act when inside the hospital.

To be sure, sailors were accustomed to disciplined spaces. On board the merchant vessel, as discussed above, sea captains enjoyed great power over mariners. But sailors understood the marine hospital, not as an extension of the workplace, but as a place of rest and, in some cases, an opportunity for leisure. Staff, such as steward Adams Bailey of the Boston Marine Hospital, often charged that healthy patients feigned continued distress to prolong their stay in the marine hospital. “Imposters,” he claimed in 1812, purposefully scarred their limbs to avoid discharge. Eventually customs and treasury officials restricted the length of hospital stays. In 1821 Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford banned the marine hospitals from admitting “incurable” and “insane” seamen. That same year Boston collector of customs Henry A. S. Dearborn emphasized that the hospitals existed only to provide “temporary relief” before mariners rejoined the workforce.

Such measures were only partly successful. Many patients, observed Benjamin Waterhouse, “make a practice of passing a great part of the night in Boston” and stumble back to the hospital grounds under the influence. Similarly, in keeping with mariners’ rough reputations, in the New York Marine Hospital, “slick and quick” theft was a daily reality. “Last night,” observed nurse James Duffe, “there was a pretty haul made of clothing and other articles out of Marine House.” The next day, Duffe recalled, with “3 constables here,” “2 men [were] discharged on suspition [sic] of stealing.”

Institutions in Early Republican Society

The marine hospitals grew rapidly in the early republic. A system that included twenty-six facilities in 1818 expanded to include ninety-five by 1858. Much of this expansion owed to the efforts of Dr. Daniel Drake, perhaps the United States’ most famous physician of the antebellum era. Drake, echoing Alexander Hamilton in the Federalist, believed that “the commerce of the West,” must serve as “a nursery of seamen” for the nation. The seemingly transcendent American desire for equal regional distribution of pork and patronage was also important. The “old Atlantic States” already had federal marine hospitals, so why did the newest states deserve any less? According to Drake, “justice requires that the advantages they would afford should be reciprocally enjoyed.” By 1860, new marine hospitals were to be found in western ports, such as Napoleon, Ark., Evansville, Ind., and San Francisco; on the hubs of the Great Lakes, such as Cleveland, Chicago, and Galena, Ill.; and even in some aging eastern ports, such as Burlington, Vt., Portland, Me., and Ocracoke, N.C. Annual hospital admissions, which ranged in the low hundreds throughout the first decade of the nineteenth century, consistently exceeded ten thousand during the 1850s.

The marine hospitals’ rapid westward expansion illustrates the durability and significance of this federal institution in a changing economy and polity. By the Jacksonian era, the center of the American economy had shifted away from foreign commerce, into domestic agriculture and manufacturing. Merchant sailors aboard river steamboats, rather than Atlantic schooners, were crucial links in this new American economy. But these laborers remained mariners nonetheless. Thus cities such as Paducah, Kentucky, demanded only a “NATIONAL HOSPITAL, with national funds, and administered by national functionaries.”

But the story of the marine hospitals in the early republic also suggests the broader significance of government and institutions in early republican society. Central government institutions touched the lives of many individuals and communities throughout the country. Long before the Interstate Commerce Commission, the New Deal, or the military industrial complex, federal institutions such as the marine hospitals provided tangible and necessary services to a vital sector of the American polity. The marine hospitals, with the military, customs service, postal service, patent office, lighthouse service, land office, military pension system, and other institutions, formed the heart of an active, vibrant, and increasingly visible early American state.

Further Reading:

On the use of a mythical stateless nineteenth century in contemporary public health debates, see William J. Novak, “Private Wealth and Public Health: A Critique of Richard Epstein’s Defense of the ‘Old’ Public Health,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 46 (Summer 2003, supplement): S176-S198.

Previous histories of the marine hospitals are: John Odin Jensen, “Bulwarks Against a Human Tide: Governments, Mariners, and the Rise of General Marine Hospitals on the Midwestern Maritime Frontier, 1800-1900” (Ph.D. diss., Carnegie-Mellon University, 2000); Ralph C. Williams, The United States Public Health Service, 1798-1950 (Washington, D.C., 1951); Richard H. Thurm, For the Relief of the Sick and Disabled: The U.S. Public Health Service at Boston, 1799-1969 (Washington, D.C., 1972); William E. Rooney, “Thomas Jefferson and the New Orleans Marine Hospital,” Journal of Southern History 22:2 (May 1956): 167-182.

Useful studies of the culture and political economy of maritime labor are: Daniel Vickers with Vince Walsh, Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail (New Haven, Conn., 2005); Paul A. Gilje, Liberty on the Waterfront: American Maritime Culture in the Age of Revolution (Philadelphia, 2004); Jesse Lemisch, “Jack Tar in the Streets: Merchant Seamen in the Politics of Revolutionary America,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser. 25:3 (July 1968): 371-407; Harold D. Langley, Social Reform in the United States Navy, 1798-1862 (Urbana, Ill., 1967).

On the history of American medicine, see John Duffy, The Healers: A History of American Medicine (Urbana, Ill., 1979); Richard H. Shryock, Medicine and Society in America, 1760-1860 (New York, 1960). Early medical journals and treatises are the best guide to the standard treatments administered in the marine hospitals. A good list of these is provided by Stephen D. Williams, “Notice of Some of the Medical Improvements and Discoveries of the Last Half Century, and More Particularly in the United States of America,” in the New York Journal of Medicine 8:2 (March 1852): 157-184.

For biographies of marine hospital officials, see George A. Zabriskie, John Gorrie, Inventor of Artificial Refrigeration (Ormond Beach, Fla., 1950); Philip Cash, Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse: A Life in Medicine and Public Service, 1754-1846 (Sagamore Beach, Mass., 2006).

The unpublished diary of James Duffe is housed at the New York Historical Society, BV Duffe James 1848. The Galena manuscript inventory is located in the National Archives, Great Lake Region, Entry 1729B, RG36, Chicago, Illinois, Collection District.

Microfilmed correspondence about the marine hospitals between local customs officials and the Treasury Department is located in the National Archives, College Park (Archives II), M174 and M175. Daniel Drake’s 1835 report on western marine hospitals is 282 Senate Document 270, 24th Congress, 1st Session, January 6, 1835.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Gautham Rao is 2008-09 Postdoctoral Fellow in the Program for Early American Economy and Society at the Library Company of Philadelphia. He will receive his Ph.D. in American history from the University of Chicago in December 2008. He has recently completed a dissertation on the state and the marketplace in the early American republic.