Sex, Vigilantism, and San Francisco in 1856

Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

When Charles Cora accompanied his mistress, Arabella Ryan, to the theater on November 15, 1855, neither had any idea that their choice of an evening’s entertainment would shape the future of San Francisco. During the play, the gentleman seated in front of the couple rose and demanded that Cora and Ryan leave the theater. Ryan, commonly known as “Belle,” was a prostitute, and the gentleman–U.S. Marshal William Richardson–felt her presence was an offense to his wife. Cora refused to leave. Two days later, when Richardson and Cora met and exchanged words over the incident, Cora pulled out a pistol and shot Richardson to death.

But what came to be called the “Cora Case” didn’t end there. It became a favorite subject in the city’s newest newspaper, the Daily Evening Bulletin. The Bulletin had been established in October 1855 by James King of William (who adopted this patronymic to distinguish himself from other James Kings). Hoping to build a successful newspaper in a city that already boasted several other major papers, King made reform his watchword. He electrified the public through his personal attacks on politicians, priests, and prostitutes, his dramatic headlines, and his pull-no-punches editorials. King had a knack for finding San Francisco’s hot button issues and weaving them together to depict the city as being in grave danger from vice and political corruption.

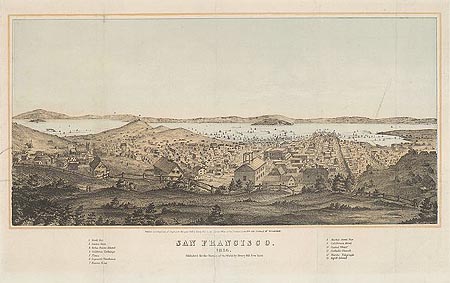

Not that he had to make it up. King’s San Francisco was full of vice and corruption. When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848, about one thousand Mexican and American settlers lived in the Mexican settlement on the bay. By 1855, nearly fifty thousand immigrants from China, Chile, Mexico, Ireland, Australia, France, and especially the United States had arrived in the city. Men outnumbered the first female arrivals by as many as ten to one. Meanwhile, tents outnumbered buildings. Gambling and prostitution were among the most lucrative businesses; hundreds of men could be found every evening in the gambling saloons, eating cheap meals, drinking hard liquor, playing cards, and paying an ounce of gold just to sit next to a woman. The boom-and-bust economy sent a few poor men to the pinnacle of success while merchants dreaded overstocked markets and plummeting fortunes. Widespread theft and arson, largely unchecked by the courts, provoked the formation of extralegal organizations to stamp out crime. One of these, the Vigilance Committee of 1851, involved seven hundred European and American merchants who hanged four men and exiled many others, mostly Australians, from the city on pain of death.

By 1855, the year Charles Cora shot and killed William Richardson, California gold production was in decline, and San Francisco had begun to take on the characteristics and aspirations of a more settled community. Some gold rush immigrants left, but others decided to settle permanently in San Francisco. They built brick houses and business establishments. Those men who could afford to, particularly middle-class Americans, sent for their wives and sweethearts until men outnumbered women only by three to two. The wives of merchants and artisans became the largest group of women in the city, outnumbering the prostitutes. Though San Francisco had changed a great deal since 1849, its most settled residents argued that vice, crime, an unstable economy, and an especially corrupt political system still threatened the security of business and family life. Prostitutes still sat, scantily clad, in windows of the city’s main thoroughfares; spectacular murders splashed across the front pages of the newspapers; well-established financial institutions crashed; and fraudulently elected city officials used their offices for personal gain.

It was in this context that James King of William, himself a family man, took up the cause of reform. Making the Cora case a symbol of San Francisco’s myriad problems, King argued that San Francisco’s most successful prostitutes, like Charles Cora’s mistress, Belle, worked hand-in-glove with gamblers, like Cora, and corrupt politicians to dominate and corrupt city politics. When Cora’s January trial resulted in a hung jury, King trumpeted: “‘Hung be the heavens with black!’ The money of the gambler and the prostitutes has succeeded, and Cora has another respite!” Throughout the winter and spring of 1856, King continued to combine attacks on prostitution with news stories alleging that Belle had bribed jurors to protect Cora. King attacked many other urban problems as well, but the Cora case effectively captured so many issues at once that King returned to it again and again.

To bolster his circulation and garner support for his reforms, King encouraged women to write to the Bulletin. The women who read the Bulletin, and probably those who wrote letters as well, were San Francisco’s newest immigrants: educated middle-class American wives from the Northeast. Recently arrived in the city, many such women were already organizing churches, sewing societies, and benevolent associations. Such activities were generally accepted in the eastern United States as appropriate public outlets for women; writing to the newspapers on political subjects was not. Yet middle-class women in San Francisco–who did not even form a women’s rights organization until 1868–seized this opportunity to participate in the public conversation over the future of the city in which they lived. As the reform movement built, in the spring of 1855, women’s participation in public political debate in San Francisco grew as well. But would this prove to be an anomaly? Would the changing and changeable culture of San Francisco allow women to participate in public politics, or would that opportunity be as short-lived as James King of William himself?

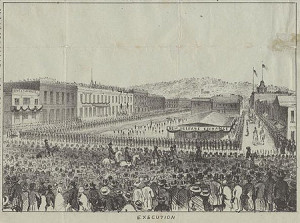

On May 14, 1856, as Cora awaited a retrial, King published a muckraking article on county supervisor and local newspaperman William Casey. As King walked home that evening, an incensed Casey shot him, and King died on May 20, a martyr to the reform cause in San Francisco. Outraged citizens organized a Vigilance Committee, which ultimately enrolled over six thousand men, particularly merchants, clerks, and skilled workers–groups whose members were likely to be permanently settled in San Francisco. These men included most of San Francisco’s white ethnic groups, with the notable exception of Irish Catholics who were virtually excluded. The vigilantes’ first act was to raid the jail, where they captured both William Casey and Charles Cora–King’s murderer and the man who best symbolized all that King had fought against in his reform rhetoric. As King’s funeral procession wound through the city on May 22, Casey and Cora were “tried” before the executive committee and hanged. Minutes before the hanging, Belle married Charles Cora in his cell inside vigilante headquarters. Afterwards, her fate, as well as that of James King of William’s broad-based reform crusade, hung in the balance.

During the next three months, the committee hanged two more men and exiled over two dozen others (mostly Irish-Catholic Democrats) for alleged political crimes. In addition, the vigilantes conducted illegal searches, suspended the law of habeas corpus, confiscated federal arms, subverted state and local militias, sought to oust elected city officials, and even imprisoned a justice of the state supreme court. In response, the governor of California declared the city of San Francisco to be in a state of insurrection and attempted to crush the committee by force. Certain prominent citizens of San Francisco, including many Irish-Catholic politicians, organized a Law and Order Party, insisting on the rule of law above all else. In their own defense, the vigilantes cited the right of revolution. A sovereign people, they argued, whose government is not only corrupt but has resisted reform, has the right to rise up and replace that government. They claimed that they had the nearly universal support of the people–the “respectable people of all classes.” To protect themselves from prosecution, the vigilantes supported the formation of the People’s Party in August 1856 (a major qualification for candidacy was public support of the Vigilance Committee), which dominated city politics for the next decade.

Both the supporters and detractors of the Vigilance Committee claimed to have not only God and the right, but also “the ladies” on their side. As Colonel Bailie Peyton put it, “The ladies are always right, and their endorsement of any cause would insure success; and it is enough to me to know that the ladies are with the Committee.” Similarly, the vigilantes’ opponents, particularly the Law and Order Party (led by John Nugent, editor of the Herald), claimed that “true women” supported their cause.

To strengthen these claims, nearly all the city’s major newspapers, even some that had never done so before, invited women to write letters on political subjects and printed them in the summer of 1856. Although women wrote on a variety of topics throughout the summer and showed their partisanship in other ways as well, the peak of women’s participation through the press coincided with the moment, in late May and early June, when the vigilantes themselves seemed uncertain about their moral authority and the direction of their movement. Needing to garner all the support they could, men on both sides of the struggle encouraged women to show their support. But some women seized the opportunity to advance an agenda of their own.

In all, about thirty letters from women appeared in May and June supporting the vigilantes. (Although it is possible that the letters may have been penned by men, the style and subject matter of the letters, read over time, suggests otherwise.) Many such letters in the pro-vigilante press simply endorsed the vigilante movement. But others, aware that the vigilantes were somewhat at a loss for an agenda, challenged the vigilantes to include sexual politics in their reform agenda. The first such letter to appear after the hangings was published on May 26, and addressed,

TO THE VIGILANCE COMMITTEE: Allow me to express to your respected body our high appreciation of your valuable services so wisely and judiciously executed. You have exhibited a spirit of forbearance and kindness that even the accused and condemned cannot but approve. May Heaven continue to guide you. But, gentlemen, one thing more must be done: Belle Cora must be requested to leave this city. The women of San Francisco have no bitterness toward her, nor do they ask it on her account, but for the good of those who remain, and as an example to others. Every virtuous woman asks that her influence and example be removed from us. The truly virtuous of our sex will not feel that the Vigilance Committee have done their whole duty till they comply with the request of MANY WOMEN OF SAN FRANCISCO

In follow-up letters, some pro-vigilante women broadened this argument to a general attack on prostitution, insisting as King had that political corruption and prostitution were interrelated. “Philothea,” for example, accused Belle Cora of killing King through her efforts to spare Cora “the just penalty of his awful crime.” Not just Belle, but prostitutes in general, inhabited a dangerous “sphere of influence, which has caused innocent blood to flow in our streets.” “Femina” took the argument even further. Making only veiled reference to Belle, Femina drew out the connections between prostitution and political corruption: “These evil and shameless women squander by thousands their ill-gotten gains to fee corrupt lawyers, to screen the criminal, whose hands are reeking with blood, from the award of justice, to uphold the gambling politicians, who in return fill their hands with plunder derived from, or stolen from, our public offices of trust . . . You can compel these women to leave our city; will you not do it?” By emphasizing that prostitution, crime, and political corruption were intertwined, Femina sought to make it difficult for the Vigilance Committee to ignore the issue of sexual politics.

Meanwhile, women writing in the anti-vigilante press also joined in the discussion of Belle Cora’s future. On June 4, “Gertrude” responded directly to “Many Women of San Francisco.” Less concerned with the standing of Belle Cora than with the legitimacy of the vigilantes’ supporters, however, Gertrude accused the pro-vigilante women of being unchristian, uncharitable, and unwomanly. Headlined “A True Woman’s Plea for the Frail Portion of Her Sex,” this letter first established Gertrude’s own credentials as a “true woman.” Modestly remarking that “although I am not a newspaper correspondent and have no desire to appear in print,” Gertrude added that, “I have no sympathy with Belle Cora or her calling (which is loathsome in the extreme).” Still, Gertrude felt that as a woman, she ought to take a more high-minded attitude. “I am a wife and a mother, and I have a woman’s heart and a woman’s feeling–a feeling that would prompt me to extend the hand of charity to Belle Cora or any of her class, as quick as to the most virtuous in the land, and feel then that I had done only my duty.” Secure in her own position, Gertrude argued that women ought not to persecute their own sex and wondered aloud whether Many Women of San Francisco feared that prostitution was contagious. Having thus subtly called these women’s virtue into question, Gertrude concluded, “I feel that every high minded, true hearted woman in San Francisco will agree with me, and for the remainder I value not their opinion.” Here Gertrude staked out the moral high ground. The true women of San Francisco would be on her side; no one else was worth listening to. Could such arguments topple the moral authority claimed by those women who supported the vigilantes?

Perhaps Thomas King (James King’s brother and his replacement as editor of the Bulletin) thought about the importance of women’s reputation, both as individuals and as Vigilance Committee supporters, when he prepared the June 2 issue of the Bulletin. Certainly that issue marked a turning point in the debate over Belle Cora as well as in the involvement of women in the vigilante movement. On page 3, King inserted a brief notice:

BELLE CORA.–We have received about a score of communications regarding this woman. We think that no good purpose can be served at this time by publishing another word about her.

Clearly, with twenty letters on the table, this subject remained important to King’s readers, especially women. But King no longer felt it deserved attention. After June 2, the number of women’s letters in the Bulletin on any subject, not just prostitution, dropped precipitously (from five per week to fewer than one per week and then to fewer than one per month). Apparently, Thomas King had not only had enough of the debate over Belle Cora, but also of women’s letters on political subjects.

In fact, the vigilantes were already turning their attention sharply away from Belle Cora and prostitution in favor of ballot-box stuffing and political corruption. As Femina’s letter appeared, the vigilantes discovered a false-bottomed ballot box, which became the preeminent symbol of their cause, fortifying the vigilantes’ claim that political corruption was rampant in San Francisco. A focus on the ballot box, however, shifted the reform agenda to traditional politics, a sphere inhabited only by male voters and officeholders, and away from sexual politics where women had been both encouraged participants in and the objects of reform.

Although the number of letters declined markedly in the Bulletin (once the most likely place for women’s letters to appear), a few women continued to publish political letters in other city newspapers. Of these, only two mentioned prostitution, and they sounded a new, more tentative, note as if questioning women’s right to be heard on this subject. “Laura Lynch,” for example, argued that while women ought to act against prostitutes, they were constrained by their “natural feeling of delicacy, which recoils from such public notice.” Still, she was not prepared to be entirely silent. “I want my say, that’s all,” she wrote.

Laura Lynch may have had her say, but in the end, the Vigilance Committee did not adopt the view of reform put forth by women like Femina and Many Women of San Francisco. Perhaps the Vigilance Committee, needing broad masculine support, did not want to alienate men by attacking prostitution. But sexual politics also played a different role in the vigilantes’ search for legitimacy than it had for James King of William. Whereas King needed sexual politics to build a broad-based reform consensus (and to attract subscribers), the vigilantes staked their futures on claims to legitimacy grounded in republican political ideals. The right of revolution existed for citizens whose government was corrupt, not for people concerned about morality, the cost of post office boxes, or other seemingly tangential reforms. Thus for its own survival, the Vigilance Committee had to demonstrate that the “ladies” were on its side, but to keep the focus of the reform movement squarely on political corruption.

The Vigilance Committee of 1856 is usually remembered for its role in reshaping San Francisco politics, attacking political corruption, and bringing the People’s Party to power. However, it is worth recalling that the Vigilance Committee reshaped gender politics in San Francisco as well. For a short time, as middle-class American women arrived in the city, ready to become active in their new community, women had a prominent place in public political discourse in San Francisco. Their opinions were sought out, listened to, and debated by other women and men. When the Vigilance Committee came to power, women continued for a brief time to have a say in public political debate. But the vigilantes set the agenda, not only for the summer of 1856 but for years afterward, and that agenda was about politics in deeply masculine terms. Vigilantes, who excluded women from committee headquarters and increasingly ignored or refused to print women’s letters in the newspapers, created a political climate in San Francisco that was anything but conducive to women’s political activism. Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that no woman suffrage organization existed in San Francisco until after the Civil War and the demise of the People’s Party.

Further Reading:

The letters referred to in this essay may be found in the following locations: Bailie Peyton in the Alta California, June 15, 1856; “Many Women of San Francisco,” in Daily Evening Bulletin, May 26, 1856; “Philothea,” in Daily Evening Bulletin, May 29, 1856; “Femina,” in Daily True Californian, May 29, 1856; “Gertrude,” in San Francisco Herald, June 4, 1856; Thomas King’s notice, in Daily Evening Bulletin, June 2, 1856; “Laura Lynch,” in Daily Evening Bulletin, June 13, 1856. Too many historians have written about the San Francisco Vigilance Committee to list them all here. For a thorough treatment of the Vigilance Committee and an excellent bibliographic essay, see Robert M. Senkewicz, S.J., Vigilantes in Gold Rush San Francisco (Stanford, 1985). For more on the political culture of San Francisco and the vigilantes, see Philip J. Ethington, The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850-1900 (Berkeley, 1994). Other recent treatments that address the role of women include Mary P. Ryan, Women in Public: Between Banners and Ballots, 1825-1880 (Baltimore, 1990); Roger W. Lotchin, San Francisco 1846-1856: From Hamlet to City (Urbana, 1974,1997); and Michelle Jolly, “Inventing the City: Gender and the Politics of Everyday Life in Gold-Rush San Francisco, 1848-1869” (Ph.D. diss., U.C. San Diego, 1998).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Michelle Jolly is an assistant professor of early American history at Sonoma State University. She is working on a project entitled, “The Price of Vigilance: Gender, Reform Politics, and the San Francisco Vigilance Committee of 1856.”