The influence of the deportation on Acadian women refugees went beyond the 1847 poem “Evangeline.” This historical event, connecting people and places across cultures, also provides a unique perspective on gender, displacement, and settler colonialism. What was it like to be a displaced woman settler in the late modern Atlantic world?

The Acadian Deportation, Women, and Refugee Resettlement in the British and French Atlantic (1755-1793)

In a sense, within an imperial context, humanitarian assistance inadvertently provided some Acadian women refugees with a platform unlike they had ever had before.

1786. In the cobblestone streets of Morlaix, nestled along the rugged coast of Brittany, the footsteps of three young Acadian sisters—Marguerite Rosalie, Anne Suzanne, and Marie Esther Richard—echoed amidst the industrious rhythm of daily life. Two of them, who were deported as children first to England and then to France, had settled as tailors in the small Breton city, where the Acadian refugee community had relocated. In a report drafted in 1786, Morlaix’s subdelegate stewardship chronicled the sisters’ plea for an exemption from the tailors’ guild, a plea borne not out of a desire for monetary gain but rather a fervent hope to safeguard their livelihood. “Since they are quite busy, they are not asking for payment. But worried they will be bothered by the tailors’ guild, they ask to be granted an exemption to practice their trade,” the stewardship remarked. The Richard sisters’ efforts to attain economic independence demonstrate how refugee women respond and recover from crises. Without the economic support of a male figure, these women encounter challenges in securing assistance for themselves, as well as for their children and parents. Paradoxically, despite being refugees, the Richard sisters managed to empower themselves, breaking away from traditional roles to assert their own agency. What factors facilitated this transformation, and how did humanitarian aid either uphold or challenge gender norms within the settler-refugee community of Acadians? Additionally, how did imperial policies intersect to advance the expansionist agendas of empires?

The scarcity of archival sources presents challenges in constructing a complete narrative of the Acadian women’s experience of the 1755 deportation. Sporadic references to these women appear in French colonial archives, state archives in the United States, and provincial archives in Canada. However, these archives do not contain testimonies or comprehensive accounts of the deportation. These administrative archives predominantly document the public sphere, wherein men typically held privileged access to direct negotiations and decision-making processes. Some Acadian women refugees, like Vénérande Robichaud (1753-1839), left letters, but many others submitted petitions or complaints that historians have ignored until today.

Exploring these documents prompts a deeper understanding of humanitarian action that needs to be reexamined from both historical and historiographical perspectives. Instead of being a simple expression of innate compassion towards distant individuals or groups, humanitarian aid often reflects various hierarchies and power relations. These dynamics can have diverse impacts on the recipients of aid, particularly in colonial contexts where former settlers suddenly turn into new refugees. Let me acknowledge something here: historians usually emphasize the transformation of refugees into settlers, who eventually become the “mothers” or “fathers” of new nations, assuming humans typically seek meaning in renewal, rather than loss. But is that really the case? Can history provide us with counter-narratives of “rebirth”?

Within the context of the French Atlantic, one could examine analogous historical events, such as the evacuation of neutral Caribbean islands like Dominica, Saint Vincent, and Saint Lucia in 1730; or the aftermath of the 1791 rebellion of enslaved people in the colony of Saint-Domingue, which pushed thousands of colonists and free people of color to flee in Louisiana; or even the deportation of settler populations from the Saint-Pierre and Miquelon islands to Nova Scotia in 1793. Among these historical forced migrations of French settlers lies the 1755 Acadian deportation, during which settlers were forcibly removed from their homes and dispersed among the colonies of British North America. As a result, former Acadian patriarchs experienced a decline in their social statuses and a significant portion of women were suddenly regarded as impoverished widows or employed as working-class laborers. Despite these adversities, some women refugees managed to assume new roles within the community. However, this process of empowerment conflicted with traditional gender roles prescribed by humanitarian aid efforts, which tended to confine women to domestic responsibilities while elevating certain male figures to spokespersons for community needs.

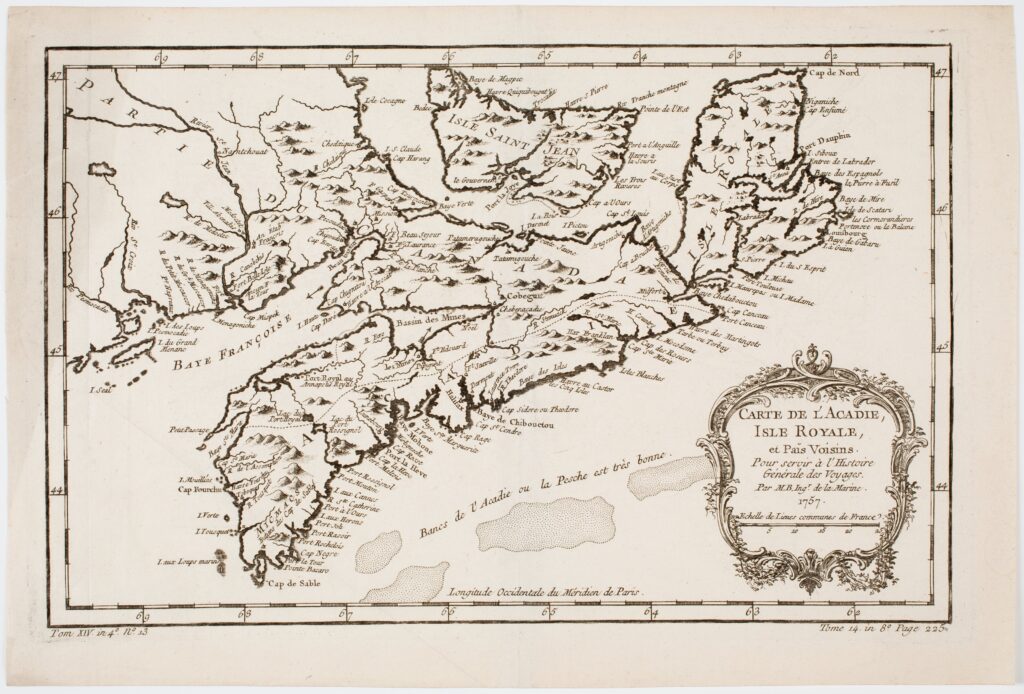

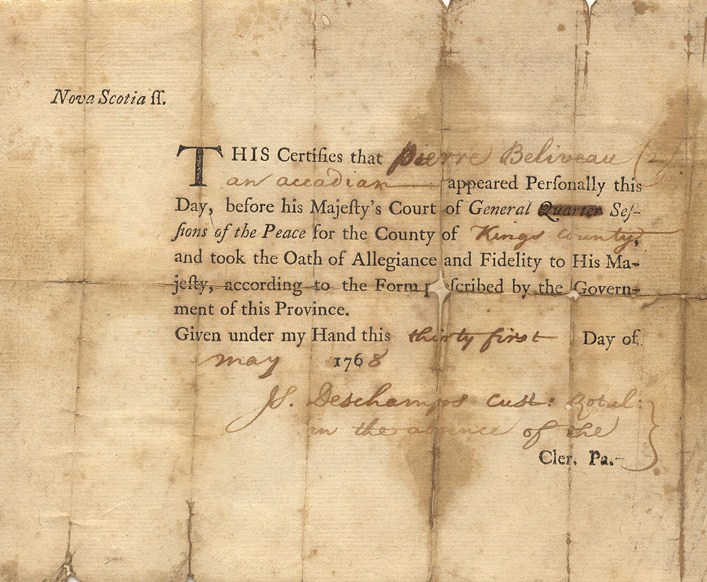

Most of the French Acadian settlers in eighteenth-century Acadia (or later Nova Scotia) hailed from rural backgrounds, where women were primarily trained in domestic tasks such as laundry, cooking, and farm work, in addition to fulfilling their maternal duties. Upon Acadia’s transfer to British rule in 1713, efforts to assimilate Acadian settlers commenced immediately. Many Acadians resisted taking the oath of allegiance to the British Crown, but once urged by the Catholic Church, which retained a strong influence, most of them finally took it. The 1755 deportation, executed by young conscripts from the neighboring colonies of New England, forcibly removed the Acadians from Nova Scotia as Great Britain did not believe they were trustworthy subjects.

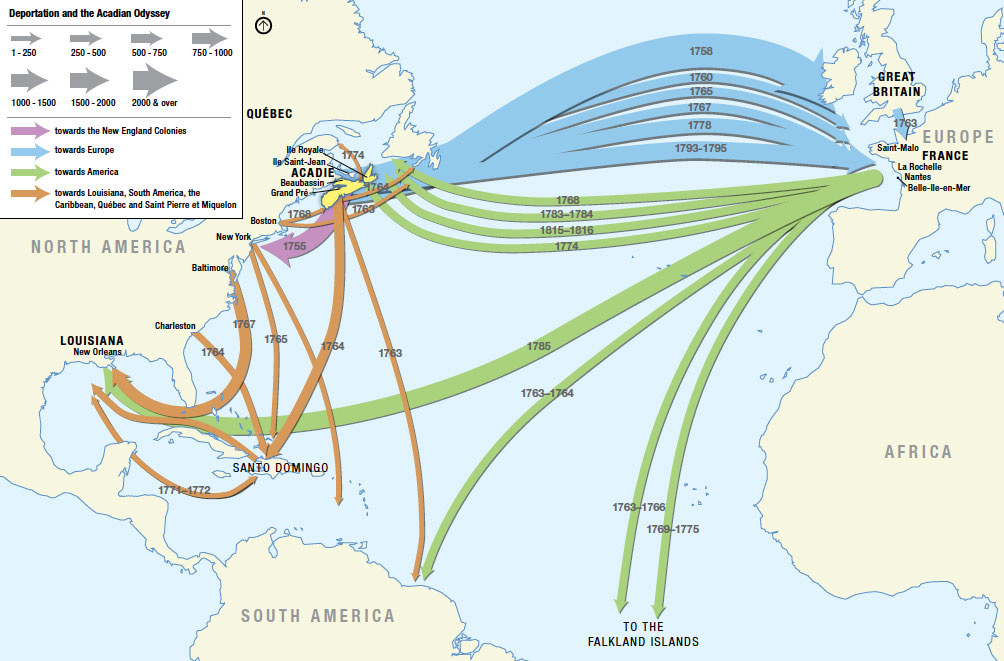

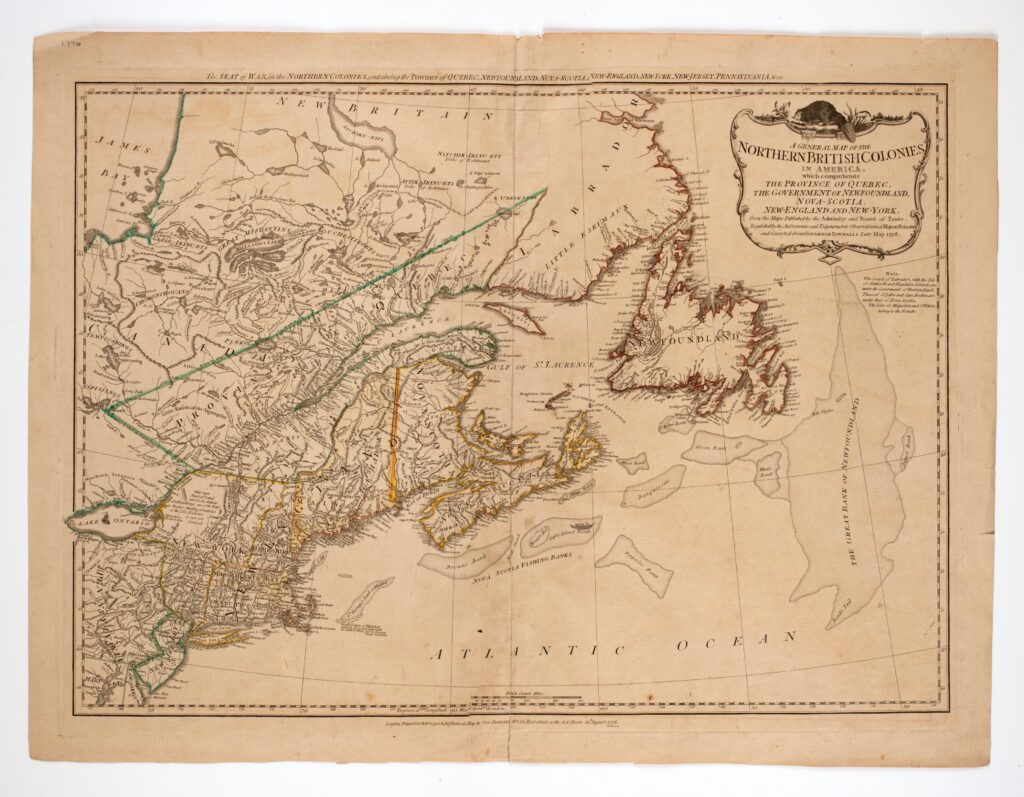

The expulsion of 1755, commonly known as the “Grand Dérangement,” refers to a series of forced migrations and deportations that began in August 1755 and extended until 1763, orchestrated by the British colonial authorities during the French and Indian War. Over the years, the Acadians had developed a distinct culture, blending French, Indigenous, and later British influences. The British colonial Governors, however, perceived the Acadians as a potential threat due to their French Catholic heritage and their geographical proximity to New France, the adversary of British colonies. Consequently, between 1755 and 1763, approximately 10,000 Acadians were forcibly removed from their homeland following the orders of Major Charles Lawrence, Governor of Nova Scotia from 1754 to 1760. These operations of expulsion and deportation were characterized by brutality and the separation of families. Acadians were dispersed to various locations, including the American colonies, Great Britain, France, Louisiana, and the Caribbean.

Women were not granted any special treatment. They often suffered in confinement aboard ships or in barracks upon their arrival in British North American colonies. The colonial authorities ordered the confinement of isolated Acadian women who had lost parents or children, in workhouses or even prisons. In 1756 a small group of Acadian women and their young children who had managed to escape deportation in the Beaubassin region were trying to flee to Ile Saint-Jean, but British soldiers arrested them. They sent them to Georges Island, not far from the port of Halifax, using many warehouses as prisons. These women were held there for several weeks until Canadian authorities arranged a transfer. These carceral initiatives reverberated within the French empire, evidenced by administrators in Guiana soliciting the establishment of an asylum, or maison de santé, in Sinnamary to accommodate the distress experienced of a considerable number of settlers, orphans, and Acadian families in 1778 and 1782. Indeed, imperial humanitarian interventions often became intertwined with expansionist interests. This duality underscores the intricate relationship between humanitarian ideals and imperial ambitions, raising questions about the genuine “altruism” behind such endeavors and the extent to which they served to legitimize and perpetuate imperial power. As a result, the unique confluence of humanitarianism and colonial violence played a significant role in the development of trans-imperial governmental experiments.

In Massachusetts, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s efforts to provide aid and support to Acadian refugees led him to agree to the group’s requests for material aid within his colony. He wrote in retrospect in his History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, “Many of them went through great hardships, but in general they were treated with humanity.” Despite these representations, Acadian women faced significant challenges, including precarious social conditions and lack of status. Acadian women refugees established in the villages of Massachusetts with their families and remained entirely devoted to domestic life. Reverend Ebenezer Parkman from the town of Westborough, Massachusetts, wrote in his diary that Marie-Madeleine and Marie-Josèphe LeBlanc, aged 16 and 13, “weave, sew and wash laundry all day.” These two sisters lived with their parents, whom Parkman welcomed in his house.

The General Court of Massachusetts issued Acts from 1755 to 1756 to distribute Acadians to different townships within the colony. While affluent townships like Cambridge readily welcomed some families without demanding immediate payment from the General Court, others, facing economic strain, either rejected Acadians outright or insisted on reimbursement for resettlement costs. Struggling with inadequate food and shelter, the refugees voiced their grievances regarding their unjust living conditions to joint committees for each county appointed by the House of Representatives and the Governor’s Council. Some Acadian male heads of households, informed by the British tradition of petitioning, initiated the practice. They drafted petitions addressed to the General Court, outlining their diverse concerns. The proximity between a few Acadian male leaders and Massachusetts elites (Louis Robichaud and Edward Winslow in Cambridge for example) allowed them to negotiate more directly with authorities to obtain their passage on French and Catholic territories. Lured by land allocations, these initiatives to leave were shaped by a settler-colonial imaginary crafted by married, middle-aged, physically capable men who imposed their will on the entire group, ultimately compelling them to relocate to Canada, Saint-Domingue, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon islands, and Louisiana, where many members of the group succumbed to illness. Other refugees, neither welcomed nor imprisoned, died wandering.

Despite enduring manifold tribulations throughout their exile, numerous Acadian women eventually reintegrated into the community upon their departure to Canada in 1765. Governor James Murray’s proclamation, published in the Quebec Gazette on March 7, 1765, offered land to new settlers, particularly Acadians. In Canada, their welfare fell on the Catholic clergy, who assigned a distinct role to Acadian women as symbols of piety and guardians of the Catholic faith. Archbishop Henri-Marie Dubreil de Pontbriand, in a missive to Quebec parishes in 1767, depicted these women as martyrs who, while enduring privations, steadfastly upheld their faith, traditions, and culture amidst adversity.

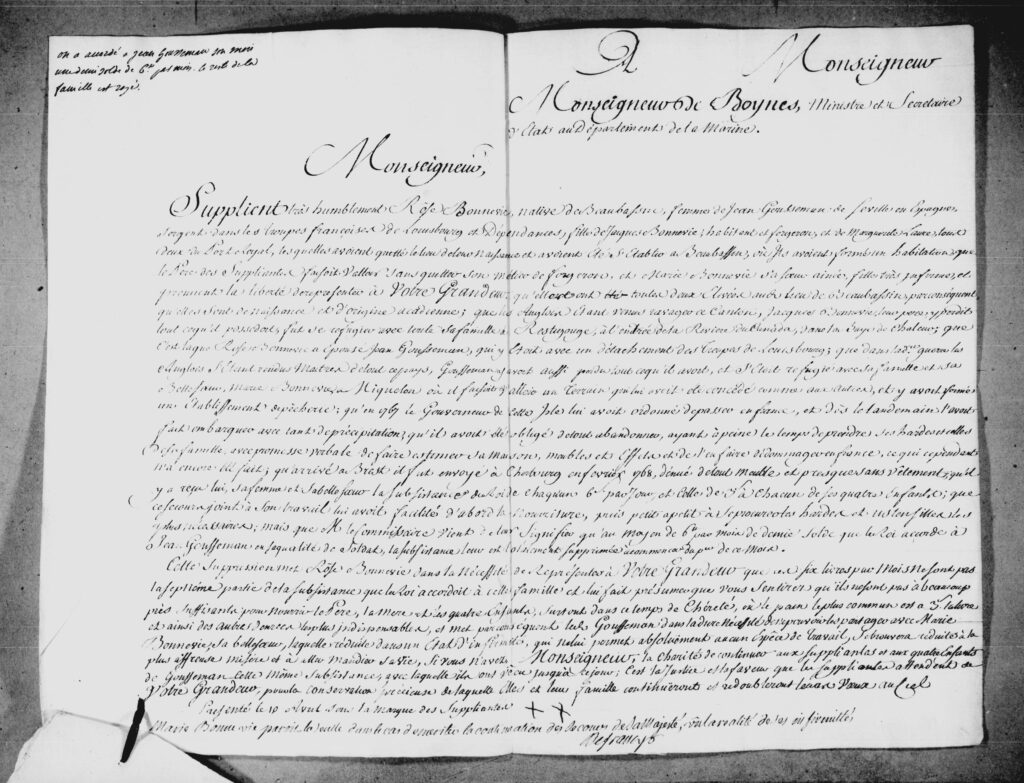

This was not always the case. Acadian women refugees were often compelled to adapt to their new realities such as in France during the 1760s and 1770s. Women’s access to the job market was often restricted, and their wages remained significantly lower than those of men. Despite these obstacles, many refugee women attempted to support themselves through various means, such as lacemaking or laundry work, albeit earning meager incomes. After spending two years in English ports, from 1758 to 1773 the French authorities agreed to provide financial assistance to Acadian refugees who had relocated there, offering asylum as well as a daily allowance for accommodation, food, and an additional support for children. However, this assistance proved inadequate to meet the diverse needs of individuals and families, especially after 1777 when the subsidy was reduced. Some Acadian women, like Rose Bonnevie, sought additional support directly from Pierre Etienne Bourgeois de Boynes, minister and secretary of the Navy from 1771 to 1774. Bonnevie highlighted the challenges faced by many female refugees in coping with extreme poverty. In a long complaint written on March 30, 1773, she told her story: “The English having come to ravage this Canton, Jacques Bonnevie, their father, lost everything he owned, had to take refuge with his entire family in Restigouge, at the entrance to the Canada River, in the Bay of Chaleurs . . . While they were refugees on the French island of Miquelon, he was given land, he founded a fishing establishment and was then sent to Cherbourg in February 1768, devoid of any furniture and almost without clothes.”

Her complaint indicates that these women had become knowledgeable about the legal culture of ancien régime France. A form of grassroots citizenship culture probably circulated among diasporic networks. Many women refugees relied on state subsidies for their survival. This situation led to requests for more subsidies and for better women’s inheritance rights, supported by the government. For many young daughters, being left without male support meant facing financial hardship. When Acadian refugee Françoise Pitre passed away, the secretary of the Navy requested in 1784 to transfer her pension to her daughter, Ozilde Lavergne, stating that she too was “Acadian.” In this context, humanitarian aid served to narrow the definition of an Acadian to the ambiguous category of “colonist” to whom the metropole owed reparations and who had the potential to inherit this identity. However, these claims to inheritance were ultimately nullified by the French Revolution and the Decree of February 21, 1791, article 3, which stipulated that “the aid should be personal and extinguished after the recipient’s death.” In the immediate post-revolutionary years, an increasing number of French settlers (including many planters and enslavers) returned to France, primarily from Saint-Domingue but also from the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique. Among them was Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie, who later became the first Empress of the French as Napoleon’s wife and is better known as Joséphine de Beauharnais.

After the issuance of the Decree of 8 Frimaire an II (November 28, 1793), which extended aid to all these refugees, the category of “colonist” (or colon in French) became clearer and more homogeneous for the administration. Maintaining colonist status required staying on French soil, so one might wonder if the end of inheriting refugee status suggests it was only a temporary condition. Moreover, one could interpret humanitarian aid to the “colonists”—no longer perceived as “refugees”—as a means of safeguarding and preserving the colonies themselves.

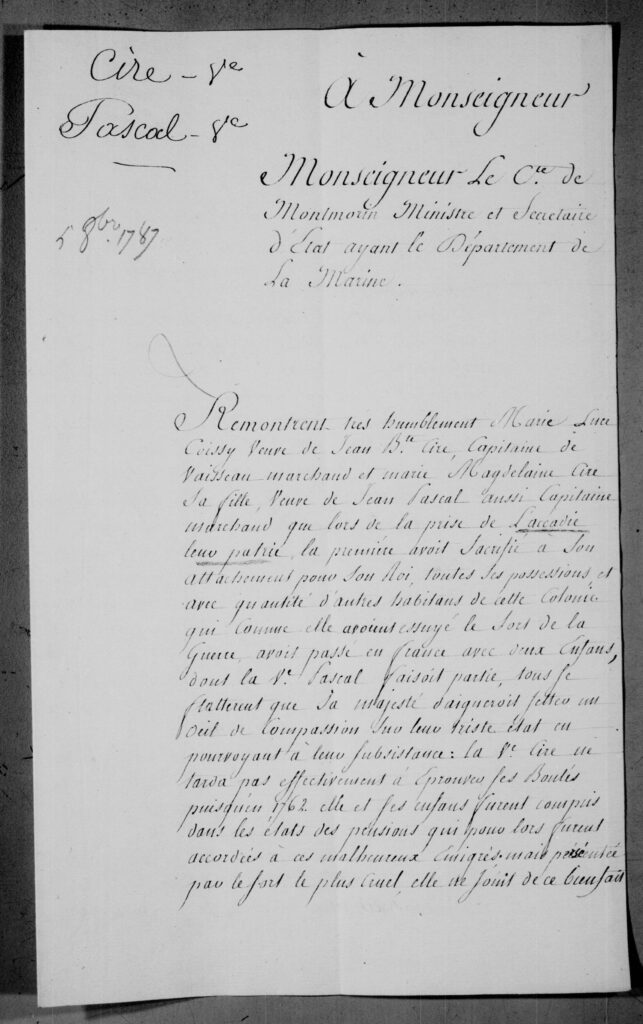

In their petitions, Acadian women used specific terminology and expressions to signify national affiliations. In the petition submitted by Marie Luce Coissy and her daughter, Marie Magdelaine Cire, to the Secretary of the Navy in Rochefort, France, in October 1787, she uses the term “patrie,” traditionally used to signify a national community in prerevolutionary France, to refer to Acadia. Women’s use of the language of nation has not been thoroughly examined by historians when compared to the ways in which Acadian men articulated national belongings and political loyalty in their petitions.

Contrary to the situation in Massachusetts, where humanitarian aid facilitated the transformation of Acadian refugees into migrants, in Canada and France, the Acadians were regarded as settlers (habitants) and at times, colonists (colons). In 1764, French foreign minister Etienne-François de Choiseul initiated resettlement projects to populate colonial territories. He therefore focused on Acadian families where women would play a reproductive role. Choiseul supported land development in Saint-Domingue, specifically at Mirebalais and Môle Saint-Nicolas, led by naval officer Count Charles Henri d’Estaing. However, this controversial project contributed to d’Estaing’s downfall. A year later, Acadian families migrated to Louisiana under harsh conditions, arriving in two groups totaling 552 individuals. The French provided them with military support and supplies, including ammunition, from the King’s warehouses in New Orleans for their resettlement in Appeloussas on April 30, 1765.

Similarly, the settlement of Acadians on Belle-Ile-en-Mer, an island off the coast of Brittany, in 1765, amid a population of less than 5,000 inhabitants, marked a significant demographic shift. Economic hardships persisted for many Acadian women, leading to complaints and petitions on “the misery” of the island. Many Acadian women on the island encountered great economic difficulties, which they often reported to members of the Catholic clergy. Madeleine LeBlanc complained to the rector of Belle-Ile-en-Mer about “the overall misery of the days.” The priest or missionary often acted as a mediator with French administrators and the refugees just as the Acadian patriarchs acted as intermediaries between Acadian families and the British administration.

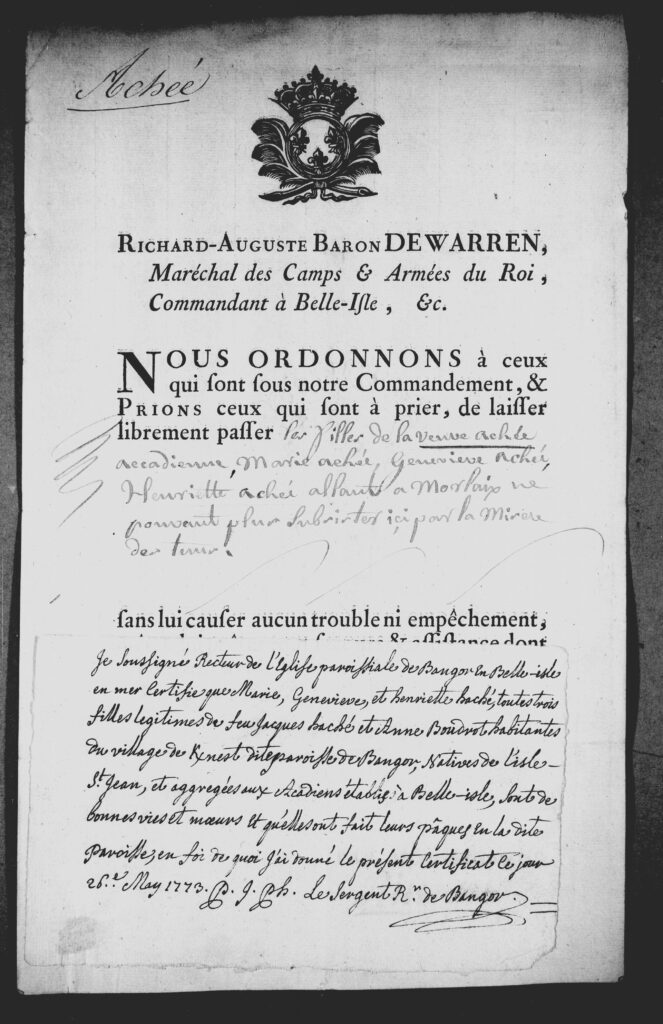

A parish priest provided the sisters Marie, Geneviève, and Henriette Achée, “daughters of the Achée widow” with a pass that attested to their “good and sound morals.” Dating from May 26, 1773, it was used to reach the town of Morlaix from Belle-Ile-en-Mer. It indicates that the sisters were “no longer able to survive here due to the poverty of the land.” The pass contained a note from the rector of the Bangor church on the island where they were established stipulating that they were “aggregated to the Acadians established on Belle-Ile-en-Mer, are of good life and morals” and that “they celebrated their Easter lent in the said parish.” These passes are central documents to understand the mobility patterns of Acadian widows and their children. Their movement was not contingent upon following a familial patriarch. Rather, they were compelled to seek authorization from a male figure of authority outside their community to facilitate their individual relocations.

Despite experiences of dispossession resulting in extreme poverty, marginalization, and lack of support from transnational diasporic networks, the humanitarian imperial resettlement plans reconfigured Acadian communities along gender lines. Some women refugees, such as widows or orphaned sisters, paradoxically gained empowerment through the acquisition of new social skills necessitated by the need to address petitions to administrations, seek employment to support themselves, or even explore new marital opportunities. When requesting assistance, these women also presented a memory of their Acadian past and community that has never been studied. In a sense, within an imperial context, humanitarian assistance inadvertently provided some Acadian women refugees with a platform unlike they had ever had before.

The examination of humanitarian politics vis-à-vis French settlers remains absent in the historiography discussing late modern Atlantic empires. The existing scholarship leaves unresolved questions about whether aid increased the former settlers’ dependence on imperial administrations (ultimately leading them to become useful “colonial communities”) or, conversely, if the various social crises they caused led to increased resistance and autonomy against imperial directives. Hence, the diverse portrayal of Acadian women by external observers challenges simple labels and probably suggests deeper cultural and historical uncertainties about the “Frenchness” or “Britishness” of their Atlantic world.

Further Reading

Archives Nationales (AN), « Secours aux réfugiés et colons spoliés », F/12/2740-2883.

Archives nationales d’Outre-Mer (ANOM), « Personnel Colonial Ancien », Collection E 1, 40, 308 ; « Secrétariat d’État à la Marine, Correspondance à l’Arrivée », Collections C13 A 45, f.115, 118, 130, C14, E 318 Bis, Aix-en-Provence, France.

Massachusetts Archives Collection, “French Neutrals”, vols. 23 and 24, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, MA.

Archives départementales d’Ile et Vilaine (ADIV) « Collection C 2453 », Archives et Patrimoine Ile et Vilaine, Rennes, France.

1755: L’Histoire et les histoires, http://cfml.ci.umoncton.ca/1755-html/.

Printed Sources

Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, from 1749 to 1774, Comprising a Detailed Narrative of the Origin and Early Stages of the American Revolution, vol. 3 (London: John Murray, 1828).

The Diary of Ebenezer Parkman, The Ebenezer Parkman Project, https://diary.ebenezerparkman.org. Henri Têtu, Charles-Octave Gagnon, Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Québec, vol. 2 (Québec: Imprimerie Générale A. Coté, 1880).

Secondary sources

Uriel Abulof, The Mortality and Morality of Nations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Saliha Belmessous, Assimilation and Empire. Uniformity in French and British Colonies, 1541-1954 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Carl Brasseaux, Scattered to the Wind: Dispersal and Wanderings of the Acadians, 1755-1809 (Lafayette: University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1991).

Christophe Cérino, « Les Acadiens à Belle-Ile-en-Mer : une expérience originale d’intégration en milieu insulaire à la fin du XVIIIe siècle », Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest 110, no. 1 (2003): 115-24.

Nathalie Dessens, “The Saint-Domingue Refugees and the Preservation of Gallic Culture in Early American New Orleans,” French Colonial History 8, no. 1 (2007): 53-69.

Hilary Doda, “Scissors, Embellishment, and Womanhood: The Material Culture of Acadian Sewing to 1755,” Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region 50, no. 1 (2021): 62-95.

John Mack Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme. The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 390.

Alan Forrest, The Death of the French Atlantic: Trade, War, and Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Netta Green, “Longing for the Beheaded Father: Inheritance and Departmental Statistics under the Directory and the Consulate, 1795-1804,” French Historical Studies, 47, no. 1 (2024): 71-102.

Naomi Griffiths, From Migrant to Acadian. A North American Border People, 1604-1755 (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004).

Christopher Hodson, The Acadian Diaspora. An Eighteenth-Century History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Allan Potofsky, “The ‘Non-Aligned Status’ of French Emigrés and Refugees in Philadelphia, 1793-1798,” Transatlantica 2 (2006), http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/1147.

Frédéric Régent, “Revolution in France, Revolutions in the Caribbean,” in The Routledge Companion to the French Revolution in World History, ed. Alan Forest and Matthias Middell (New York: Routledge, 2016): 61-76.

Peter Stamatov, The Origins of Global Humanitarianism: Religion, Empires and Advocacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Adeline Vasquez-Parra, “Local Affairs or Imperial Scandals? The Rise of an Atlantic Legal Culture of Citizenship among Colonial Communities in the French Caribbean (1697-1789),” Journal of Early American History 12, nos. 2-3 (2022): 211-47.

Adeline Vasquez-Parra, Aider les Acadiens ? Bienfaisance et déportation, 1755-1776 (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2018).

Many thanks to the George Godfrey Rodrigue Jr. Family Trust for granting permission to use the unique artwork by Louisiana artist George Rodrigue (1944-2013); to François LeBlanc at the Centre d’Etudes Acadiennes Ansselme Chiasson, Université de Moncton, Canada for providing the oath of allegiance; and to Netta Green, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for bringing the « Secours aux réfugiés et colons spoliés » to my attention.

This article originally appeared in June 2024.

Adeline Vasquez-Parra is an associate professor in American history and civilization at the University Lumière of Lyon in France and researcher at the Laboratoire Triangle UMR 5206. She has contributed articles on the Acadian deportation to scholarly journals such as Revue Historique, Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, Acadiensis, and the Journal of Early American History. She is currently working on a comprehensive history of the province of Québec from its origins to the present day.