History explains; film shows. But how does film show slavery, and to what end? And why is slavery such a vexing problem in film, in museums, in national parks, or any medium of public historical representation? To ask these questions is almost to pose a commonplace: why is evil, oppression, trauma, and great conflict in the past difficult to confront in a modern democratic society?

Some answers can be found in the history of representation itself. In the wake of the Civil War, Americans began constructing images of slavery that were almost pure wish-fulfillment. By the 1880s and 1890s, a literary calculus was at work in sentimental fiction about the Old South. The freedpeople and their sons and daughters were the bothersome, dangerous antithesis of the noble catastrophe that the Confederacy’s war increasingly became in reminiscence and in Lost Cause tradition. Omnipresent, growing instead of vanishing, blacks had to have their place in the splendid disaster of the war, emancipation, and Reconstruction. So in the works of several widely popular dialect writers (the Plantation School), especially Thomas Nelson Page, blacks were rendered faithful to an old regime, as chief spokesmen for it, and often confused in–or witty critics of–the new. The old-time plantation Negro emerged as the voice through which a transforming revolution in race relations dissolved into fantasy and took a long holiday in the popular imagination.

In the Gilded Age of teeming cities, industrialization, and political skullduggery, Americans needed another world to live in; they yearned for a more pleasing past in which to find slavery. Page, and his many imitators, delivered such a world of idyllic race relations and agrarian virtue. An unheroic age could now escape to an alternative universe of gallant cavaliers and their trusted servants. Page’s best-selling world of prewar and wartime Virginia was inhabited by the thoroughly stock characters of Southern gentlemen (“Marse Chan”), gracious ladies (“Meh Lady” or the “Mistis”), and the stars of the show, the numerous Negro mammies and the loyal bondsmen (“Unc’ Billy,” “Unc’ Edinburgh,” or “ole Stracted”). In virtually every story, loyal slaves reminisce about the era of slavery, and bring harmony to postwar plantations by ushering Southern belles and good Yankee soldiers to reconciliation and matrimony. How better to forget a war about slavery than to have faithful slaves play the mediators of a white folks’ reunion?

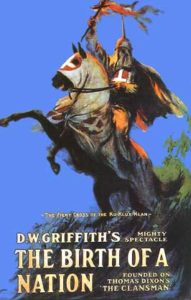

By the time D. W. Griffith and Thomas Dixon began the collaboration in 1913 that would produce Birth of a Nation (1915), this genre of American fiction had become a nearly impenetrable fog of melodrama and racism through which most Americans could hardly see alternative visions of slavery and its aftermath. Griffith, who grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, came of age in the heyday of the Lost Cause. A lover of the Southern martial tradition and Victorian melodramas, and eager to portray a lost rural innocence in the new urban age, he was in New York by 1908, acting and making short films.

As the fiftieth anniversary of the war approached in 1909-11, Griffith made several Civil War melodramas. In these films, stock scenes and characters abound: rebel soldiers going off to war with black field hands cheering, genteel but sturdy Southern white women, Confederate and Union soldiers (sometimes brothers) shaking hands while wrapped in the folds of their flags, and ubiquitously, loyal slaves saving or dying for their masters. Indeed, during the semicentennial of the war, American theaters were saturated with Civil War films lasting fifteen to twenty-five minutes, with some ninety-eight produced in 1913 alone. The films’ subtitles repeatedly portrayed the slaves as “happy, contented, and well cared for . . . joyous as a bunch of school children,” as though the obsequious characters on screen did not adequately convey the message. Black characters in these films themselves carry the historical lesson that slavery was not the cause of the war, and its destruction was the lingering misfortune of the nation and the black race. Not only do black mammies and butlers die saving their white folks from marauding Yankees, but in some films, whole families and slave quarters defend plantations, and thereby the South, from its destruction.

In Birth of a Nation, Griffith gave his well-plied audiences the message not only that blacks did not want their freedom, but also that emancipation had been America’s greatest disaster. The lasting significance of Birth of a Nation is that it etched a story of Reconstruction, and of the noble restoration of white supremacy, into American consciousness. The film’s epic visualization of a necessary and noble birth of the Ku Klux Klan to thwart the schemes of deranged radicals and sex-crazed blacks makes this the most controversial film in American cinematic history. Indeed, visually and historically, especially given the persistence of neo-Confederate and genteel white supremacist traditions in America even at the turn of the twenty-first century, historians and filmmakers alike are still responding to the messages ingrained in our historical memory by Griffith’s epic.

Can we imagine any other film carrying such a politics for so long? A friend tells me that in her high school social studies class in 1970 in St. Louis, Missouri, a group from the Black Student Union broke into the classroom, tore the reel from the projector, and burned Birth of a Nation in front of teacher and students. Perhaps only some forms of pornography and some Cold War films may ever have caused such acts of resistance to the images on a screen. Such visceral responses to Birth of a Nation suggest that Americans have difficulty assessing the meaning of slavery outside of a moral language of good and evil and black and white. Slavery is widely seen as an economic institution, but determining its historical responsibility is an inherently moral act. And the origins of the slave trade itself, at least in the popular imagination (and despite decades of scholarship), have not been dislodged from images of benighted Africans stolen from their homelands by avaricious Europeans. The deep complicity of African societies in the slave trade has not found a comfortable place in historical memories on the American side of the Atlantic.

Moreover, any attempt to understand the legacies of slavery requires for some a confrontation with shame–heritage consciousness and ancestor worship, both growing trends in our world, tend to be quests for a positive and uplifting past. Few people would choose to have their ancestors be slaveholding capitalists who made their livings from the blood and liberty of human property; and few would choose to descend from chattel slaves who lost their homelands and liberty, and had to rise from illiteracy and cotton fields they could never own. Racial slavery has never fit well into a popular expectation in America that our history is about progress, that we are a people of good will who solve all of our problems. Broadly speaking, public expectations of the past are at stake in any attempt to represent racial slavery in film. But this doesn’t release anyone from historian Natalie Zemon Davis’s admonishment against “wish-fulfillment” in depicting the history of such a subject. Americans like to be pleased by their history, and that enormous backdrop of melodrama and wish-fulfillment about slavery still stands in the path of genuine understanding.

In her Slaves on Screen: Film and Historical Vision, Davis writes optimistically about the “differences between telling history in prose and telling history on film.” Those differences, especially in approach to canons of evidence and in portrayal of emotive drama, are striking and troublesome. But Davis wants to keep filmmakers’ feet to the fire when it comes to truth telling. “Historical films should let the past be the past,” she writes. “The play of imagination in picturing resistance to slavery can follow the rules of evidence when possible, and the spirit of the evidence when details are lacking.” In an appeal that can apply to documentary filmmakers as much as movie directors, Davis warns that “wishing away the harsh and strange spots in the past, softening or remodeling them like the familiar present,” can only make building a desired future harder. Take that Steven Spielberg and Ken Burns.

Davis’s admonition is that filmmakers should preserve the integrity of real stories, and not invent alternatives when they don’t like the evidence. “Wish-fulfillment,” she says, “should not steer the imagination in a historical film.” Davis’s argument is not a naive proposition, especially given her own experience as a very active creative force behind the dramatic feature film, The Return of Martin Guerre (1982), as well as with some recent efforts to confront slavery on screen. But on the subject of American slavery, filmmakers have always had an enormous sea of sentimentalism and melodrama to cross before even considering the subject. From several experiences working with documentary filmmakers and screenwriters, I have come to cautiously share Davis’s optimism about the possibilities for films about slavery. In the United States, PBS has become a frequent outlet for good films about African American history generally and slavery particularly. WETA in Washington, D.C., and especially the “American Experience” project sponsored by WGBH in Boston, have been homes to many young and talented filmmakers and writers in recent years. In 1993-94, I worked with Orlando Bagwell on his Frederick Douglass: When the Lion Wrote History, the first major attempt to represent Douglass’s life on film. In that film, Bagwell and his crew were rushed by an early air date, but they produced a film still in wide educational use; they created a Douglass of heroic proportions, but one who is complicated by the transformations in his life. From that one experience I learned that many filmmakers are themselves good historians; Orlando and his collaborators read everything on Douglass, and they delivered a Douglass rooted in historical time.

For his remarkable four-part, six-hour series, Africans in America, Bagwell and his producers invited me and three other historians to a two-day seminar for the rough-cut screenings (about a year before air dates). This was, again, a lesson in how documentary filmmakers do want to get the history right, at the same time they need to teach historians to think in filmic terms. With Barbara Fields, Gerald Gill, and Sylvia Frey, I sat through intensive, all-day discussions with the teams of producers and writers on each of the four segments of Africans. We had many disagreements and recommendations; all the discussions were taped and transcribed.

Our subject, of course, was how to represent the story of slavery from the slave trade to emancipation in six hours. Specific documents, quotations, and images were openly debated. But the impressive fact was that all of the filmmakers really wanted our criticisms. They were very attuned to what we deemed accurate and historically sound. At the end of the day we were all involved in an interpretive enterprise–debating how much of African complicity in the slave trade to stress, how and when a Christianization process set in among colonial slaves, just what interpretation of the American Revolution the lens of slavery and black freedom provided, how to capture the relationships between black and white abolitionists, which fugitive slave story was best representative of that crucial element of resistance in the 1850s, how to tell the story of slavery as both oppression and survival, and many more questions. We ventured into the filmmakers’ domain, begging for more interpretive commentary here, and less dramatic recreation there, less music in one place, and more talking heads in another. In every case, of course, we were trying to recommend good history that had to be converted into a film narrative. There are many aspects to quibble with, but Africansbecame American history with the story of slavery and race brought to the center of the national narrative.

Yet all of us who have worked with filmmakers, in reading scripts or as interviewees, have had other less encouraging experiences as well. In the early and mid-1990s I worked as an advisor for director Charles Burnett and producer Peter Almond on a dramatic film about Douglass. Burnett wrote many drafts of an impressive script and used me as a sounding board and reader. His was a psychological portrait of Douglass, created from rich documentation, a tale of a brilliant former slave who could never be fully secure in the world of intellect and radical abolition he had entered. Burnett juxtaposed Douglass’s home and family life in Rochester, New York with President Abraham Lincoln’s home at the White House in the Civil War years in interesting ways. He also probed Douglass’s relationships with other abolitionists, black and white.

Burnett would have given us a somewhat tormented young Douglass trying to shape and make history in ways he only half controlled; it was a story about Douglass, but also very much about slavery tearing apart the American nation-state. Lawrence Fishburne had been approached about playing Douglass. But that film has never been made because the company most interested, Turner Broadcasting, never liked the scripts. They wanted a more romantic story of Douglass–more about the war and the women in his life, in short, more melodrama. The scripts were submitted to a second writer who cut them virtually in half; the project languishes like many earlier efforts to present slavery on film. Film can be a blunt instrument for subtlety and nuance. In prose and poetry, a writer can capture the travail and spirit of a human soul. Films, especially documentaries, are married to realism, to the too often assumed power of visual artifacts. But no artifact interprets itself, no picture has meaning solely on its own. And the pictures from the past privilege those elements of history that were more frequently photographed or painted; material culture dominates in the visual record over human aspiration or suffering. So, when historians and filmmakers collaborate they are always reminded of the limitations of this mixed medium. When I first met the original script writer on the Douglass documentary, he told me that he begins every project by reading the children’s literature on the subject first. Initially I was worried about this, but came to understand his point when I realized that Douglass’s life would have to be boiled down to approximately a seventy-five-page script.

But such limitations do not release us from engaging filmmakers and helping them make good history. From my recent work on Civil War memory I came across a story that might provide an opening scene for some enterprising filmmaker eager to construct continuing answers to Birth of a Nation. It is a story worth telling not merely for its sentiment, but because it was all but lost in the historical record. After Charleston, South Carolina was evacuated in February 1865 near the end of the Civil War, most of the people remaining among the ruins of the city were thousands of blacks. During the final eight months of the war, Charleston had been bombarded by Union batteries and gunboats, and much of its magnificent architecture lay in ruin. Also during the final months of war the Confederates had converted the Planters’ Race Course (a horse track) into a prison in which some 257 Union soldiers had died and were thrown into a mass grave behind the grandstand.

In April, more than twenty black carpenters and laborers went to the gravesite, reinterred the bodies in proper graves, built a tall fence around the cemetery enclosure one hundred yards long, and built an archway over an entrance. On the archway they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.” And with great organization, on May 1, 1865, the black folk of Charleston, in cooperation with white missionaries, teachers, and Union troops, conducted an extraordinary parade of approximately ten thousand people. It began with three thousand black school children (now enrolled in freedmen’s schools) marching around the Planters’ Race Course with armloads of roses and singing “John Brown’s Body.” Then followed the black women of Charleston, and then the men. They were in turn followed by members of Union regiments and various white abolitionists such as James Redpath. The crowd gathered in the graveyard; five black preachers read from Scripture, and a black children’s choir sang “America,” “We Rally Around the Flag,” the “Star-spangled Banner,” and several spirituals. Then the solemn occasion broke up into an afternoon of speeches, picnics, and drilling troops on the infield of the old planters’ horseracing track.

This was the first Memorial Day. Black Charlestonians had given birth to an American tradition. By their labor, their words, their songs, and their solemn parade of roses and lilacs and marching feet on their former masters’ race course, they had created the Independence Day of the Second American Revolution.

To this day hardly anyone in Charleston, or elsewhere, even remembers this story. Quite remarkably, it all but vanished from memory. But in spite of all the other towns in America that claim to be the site of the first Memorial Day (all claiming spring, 1866), African Americans and Charleston deserve pride of place. Why not imagine a new rebirth of the American nation with this scene?

Further Reading:

Natalie Zemon Davis, Slaves on Screen: Film and Historical Vision (Cambridge, Mass., 2000). David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, Mass., 2001). Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900-1942 (New York, 1977).

This article originally appeared in issue 1.4 (July, 2001).

David Blight teaches history and black studies at Amherst College. He is the author of Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Baton Rouge, 1989), and Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, Mass., 2001). He has been a consultant to several documentary films, including the PBS series Africans in America (1998).