“Nick and Josie, John and Mosie.” Or “Johnnie, Josie, Nickie, Mosie.” I haven’t been able to source this one, but I’ve also heard the four Brown brothers—Nicholas (1729-91), Joseph (1733-85), John (1736-1803), and Moses (1738-1836)—referred to as “Nick, Joe, Jack, and Moe.”

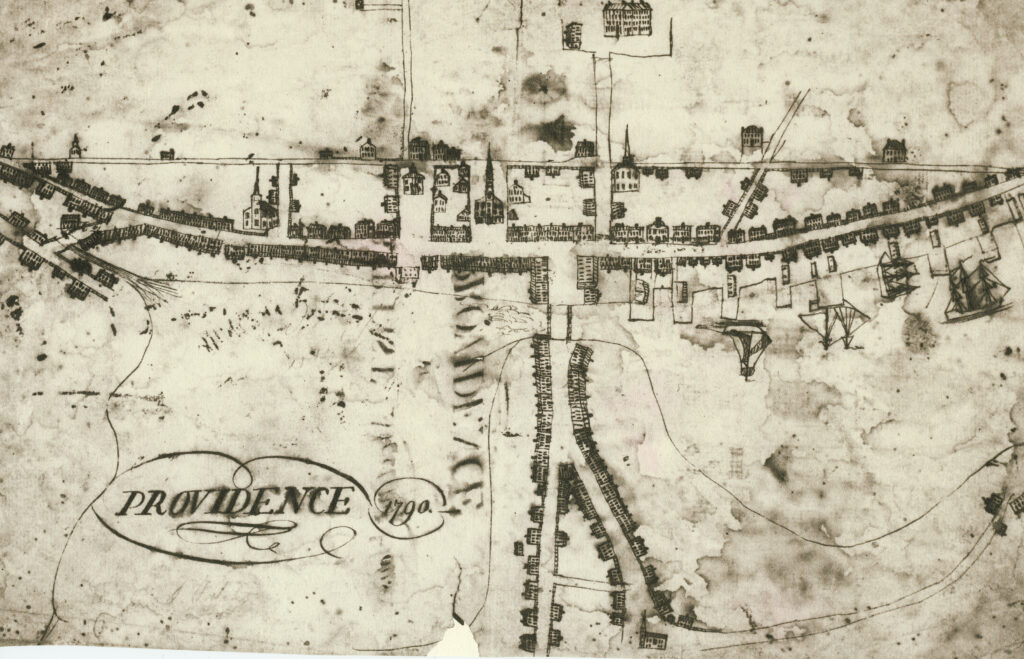

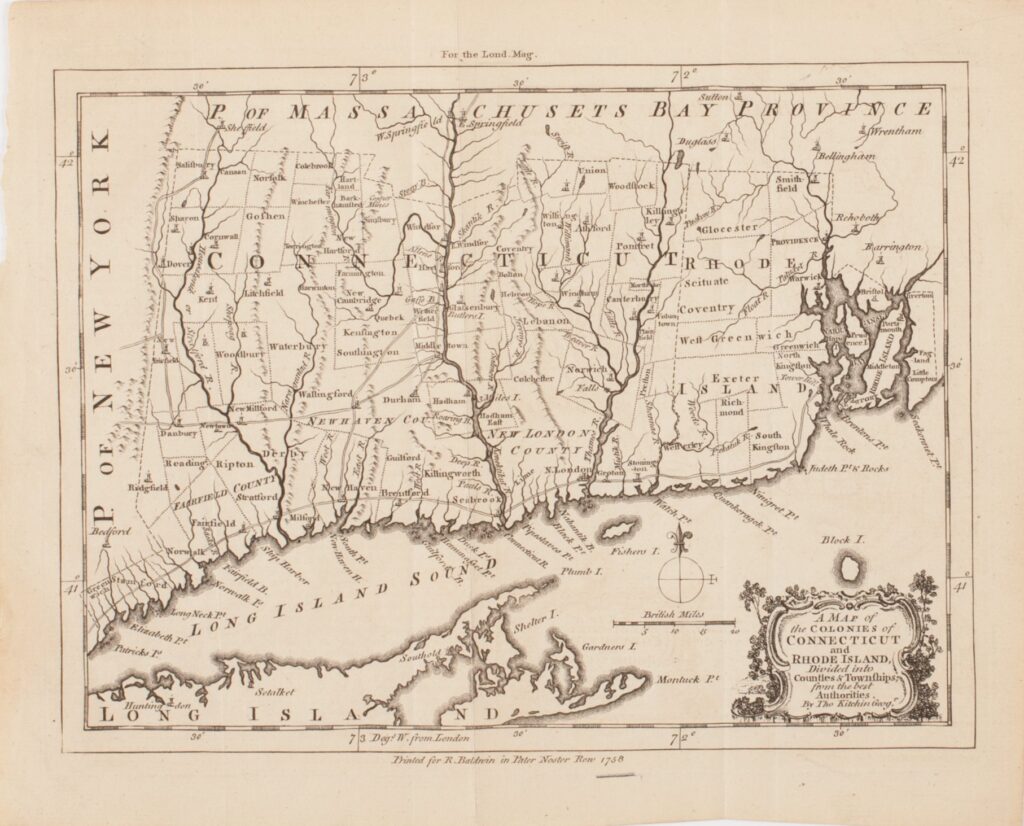

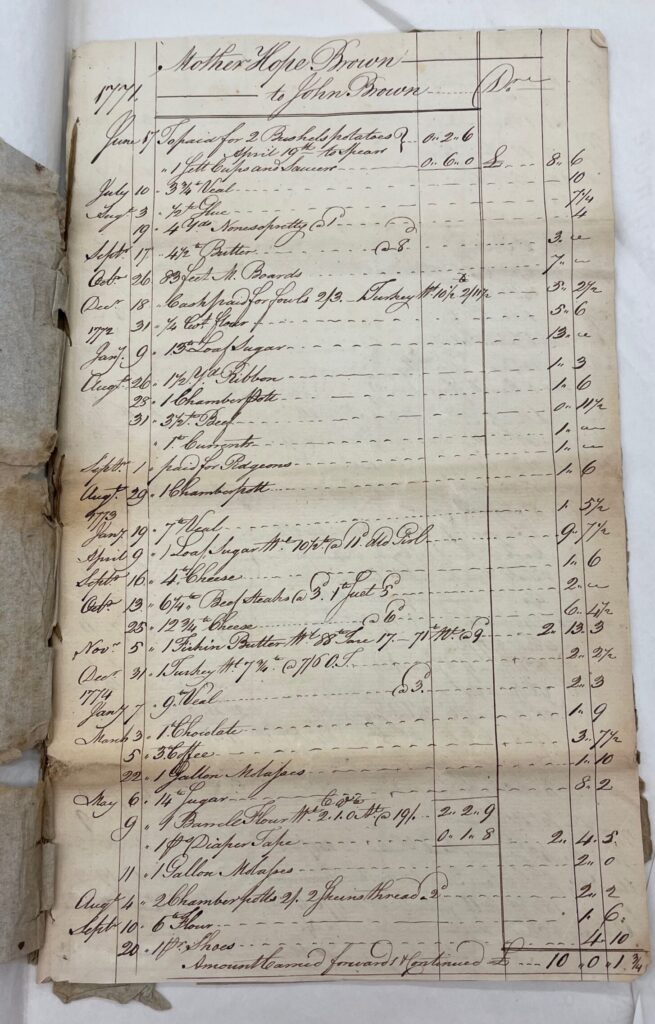

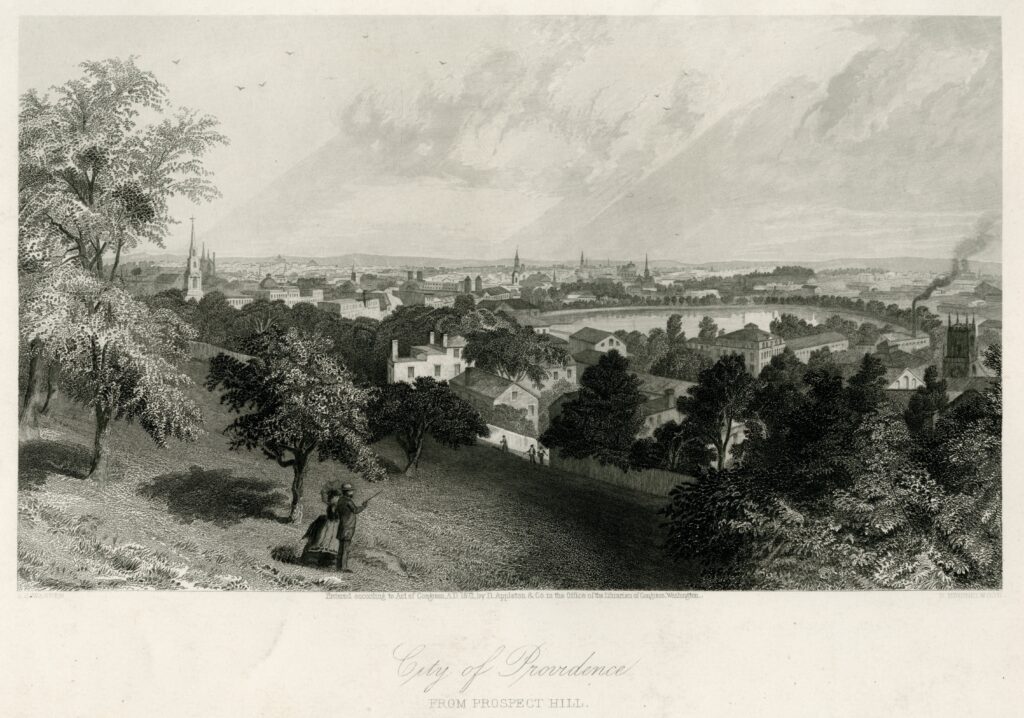

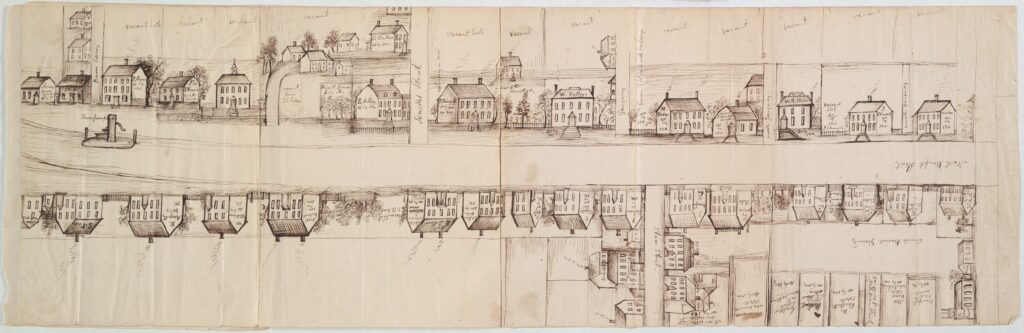

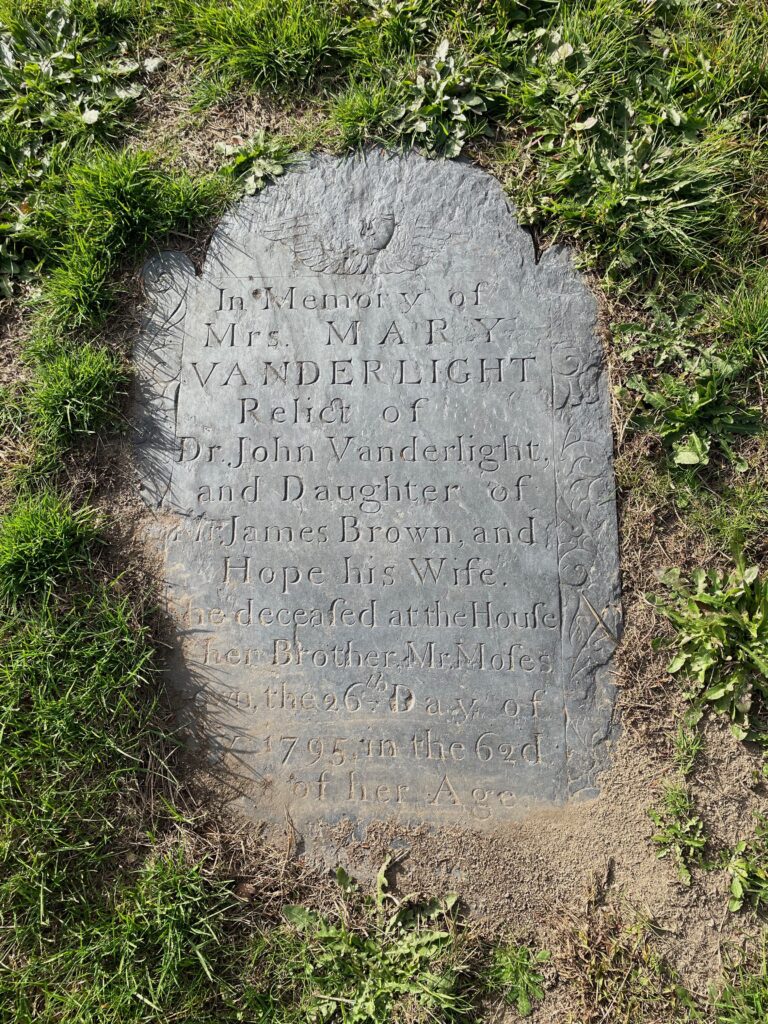

Ubiquitous in the annals of early American commerce, politics, and slavery and in the history and lore of Providence, Rhode Island, the wealth from the Brown brothers’ extensive merchant trading and companies was the foundation for centuries of family philanthropy and was instrumental in the founding of Brown University. The Browns are both emblematic of the kinds of wealth that was generated through trade in the eighteenth century, and distinctive for their success and long legacies. Those legacies in Providence and beyond are many, including the library where I work, named for the originating collection of John Carter Brown, a grandson of Nicholas Brown. Joseph Brown helped design the university’s first building, University Hall. The John Brown House is a cornerstone of the Rhode Island Historical Society’s programming. The Moses Brown School remains a pillar in the city. The brothers were such a potent foursome, then and since, that when their powerful-in-her-own-right mother died in 1791, she was memorialized on her gravestone as “the mother of Nicholas, Joseph, John, and Moses Brown.”

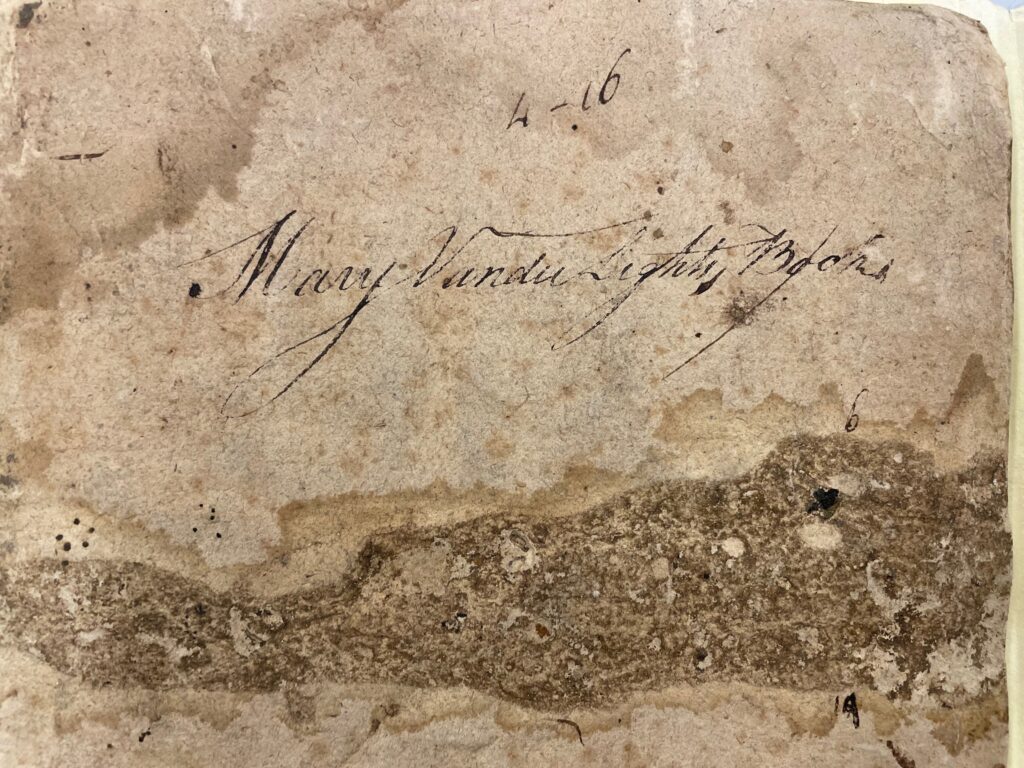

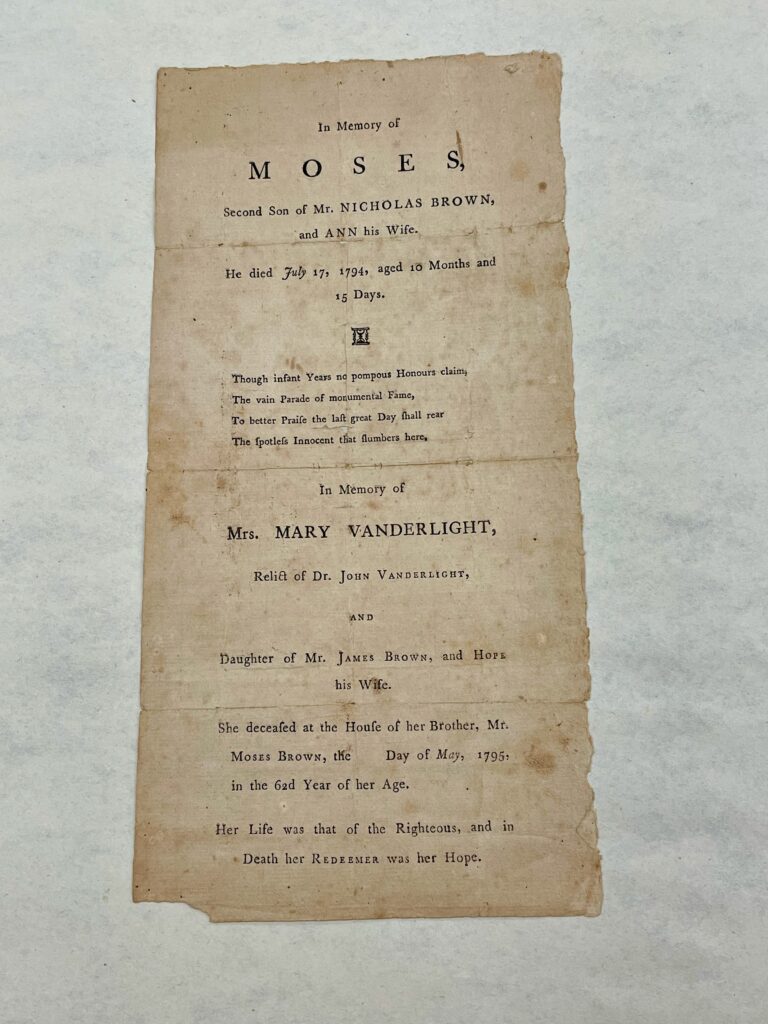

So much for Mary, their sister and their mother’s only daughter.