New York City and its bodies politic, 1800-1860

On Sundays, the work of disinterring the many thousands of bodies from New York’s old Potter’s Field—or paupers’ burial ground—halted for the week, and the lot was unguarded, permitting a scene of macabre joviality. For most of the 1850s, in an open lot at Fourth Avenue and Forty-ninth Street, crowds gathered to view hundreds of unearthed pine caskets, broken apart during the week by workers’ spades and picks, their contents spilling into public view. While the genteel gazed upon the remains, vagrant children played kickball with disembodied skulls, and dogs growled over the long bones of arms and legs.

Even in the chaotic bustle of antebellum New York, this desecration did not escape scrutiny. “Is our City always to be disgraced by some public exhibition?” asked a subscriber to the New York Times in 1858. “For the sake of decency, do call the attention of our City authorities to the exhibition of coffins, skulls and decayed bodies lying exposed.” But the city authorities were already well aware of this gruesome public nuisance. Indeed, the public-health controversy and moral outrage that accompanied the disinterment of the city’s old Potter’s Field and the removal of the bodies to the new locations on Randall’s and Ward’s Islands had been brewing since at least the first decade of the nineteenth century.

The phrase Potter’s Field was not specific to New York City’s paupers’ burial ground. It originated in Matthew 27:7: “And they took counsel, and bought with them the potter’s field, to bury strangers in.” “Potter’s field” referred to a place where potters dug for clay, and thus a place conveniently full of trenches and holes for the burial of strangers. For nineteenth-century New Yorkers, the biblical veneer of the term was perhaps an antidote to one of the distressing costs of life in the chaotic new democratic city. As some prospered, hundreds of others died, remembered by no one and memorialized by nothing. At least, in Potter’s Field, they lay under a vague biblical cope.

The first Potter’s Field burial ground in New York City was located at the site of what would become the militia parade ground and city park at Washington Square. On this nine-and-a-half-acre plot, at the city’s pastoral northern edge, lay the densely packed corpses of about 125,000 “strangers,” many of whom had died during two separate yellow-fever epidemics between 1795 and 1803. Not surprisingly, local residents who had fled crowded lower Manhattan for country estates in the region came to find in Potter’s Field an intense nuisance. Whatever sympathy anyone had for the anonymous dead did not supersede wealthy New Yorkers’ sense of entitlement when it came to their comfortable insulation from the city’s darker side. In a letter to the Common Council, they wrote, “From the rapid Increase of Building that is daily taking place both in the suburbs of the City and the Grounds surrounding the field alluded to, it is certain that in the course of a few years the aforementioned field will be drawn within a precinct of the City.” Within the first two decades of the nineteenth century, their prediction had been realized, and the Potter’s Field began a lengthy series of migrations in a vain effort to stay a step ahead of the city’s relentless growth.

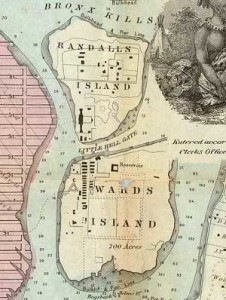

In 1823, the city moved Potter’s Field to an empty lot at the corner of Forty-ninth Street and Fourth Avenue—what would then have been the far northern reaches of the metropolis. This place served as the Potter’s Field until the 1840s when, as the city grew northward, it was relocated once again to Randall’s Island in the East River. Cast off the Island of Manhattan like so many family farms, Potter’s Field would no longer clash with the New Yorkers’ Victorian sensibilities or inhibit the Manhattan real-estate boom.

Just south of Randall’s Island, separated by a treacherous, narrow channel known as Little Hell’s Gate, was Ward’s Island, the site of another Potter’s Field in the mid-1850s. Both Randall’s and Ward’s Islands already housed other city institutions for the indigent, including the Emigrant Refuge and Hospital, the State Inebriate Asylum, the juvenile branch of the Almshouse Department, and the headquarters for the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents. As one guide to New York and its benevolent institutions observed, “multitudes of persons went from the dram-shop to the police-station, and from the police courts to the Workhouse from whence, after a short stay, they returned to the dram shop . . . until they at length died on their hands as paupers or criminals, and were laid in the Potter’s Field.” For most of New York’s institutionalized underclass, there was literally a direct path from the door of the asylum or workhouse to the Potter’s Field.

Relocating the city’s cemetery from Manhattan’s urban grid to an island in the East River did not put an end to the city’s problem with the indigent dead. In 1849, the Daily Tribune reported on the political and legal wrangling between the governors of the Almshouse and the Common Council (the nineteenth-century name for the City Council), the former seeking to wrest authority over Potter’s Field from the latter. The governors cited the poor management of the paupers’ burial ground, which the Tribune referred to as “that den of abominations,” as evidence that the Common Council was unable to manage the Potter’s Field. “We do sincerely trust somebody will shoulder the responsibility of the Potter’s Field,” the Tribune pleaded, “and rid the Island of the abomination before the advent of another warm and perhaps an epidemic season.”

The Common Council and the Governors of the Almshouse traded letters, pleas, and vitriol for the better part of a decade. In May of 1851, the Governors warned the Common Council that, “the land now appropriated [for the Potter’s Field] is now nearly full, and the small space left for further interment (which now average upwards of one hundred per week), renders prompt action necessary.” Four years later, it was still unclear who had control over the Potter’s Field, and conditions were worsening. By this time, there were two burial grounds for paupers: the primary site on Randall’s Island and a smaller one on Ward’s Island to the south. The Board of Governors proposed to expand the Ward’s Island site in 1854, and the Times supported the proposition, suggesting that “it is time that the remains of paupers were interred in some quarter better fitted for their last resting-place than the one now used on Randall’s Island.” In their reports to the Board of Health and the Common Council, the Governors of the Almshouse urged that, “humanity, a due regard for the living, and a sense of proper respect for the dead” be part of any effort “to remedy the existing and impending evils.”

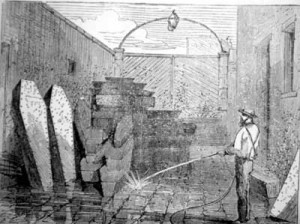

In the meantime, the disinterment of bodies at the old site on Fourth Avenue aroused its own controversy. In 1851, a plan was adopted by the Common Council to expand Forty-ninth Street through the old Potter’s Field, which required the disinterment of thousands of bodies. This project stretched on for nearly the entire decade, accompanied by foot-dragging and corrupt contractors. Commenting on the enormity of the project, the Times reported in the spring of 1853 that “the City Authorities are cutting a street through the old Potter’s Field . . . where so many victims of the Cholera were hurriedly interred in 1832. The coffins were then, in many instances, stacked one upon another; and now, in digging through the hill, the remains of twenty coffins may be seen thus piled together.”

As with the active Potter’s Field, the old paupers’ burial ground aroused no small amount of controversy. In the summer of 1858, the Times again reported on the work, claiming that “within three weeks past about 3,000 skeletons have been exhumed from the old Potter’s Field . . . and removed to Ward’s Island.” The winter of 1858-59 passed without any further exhumation, and “meantime the thin layer of earth which covered some hundred half-decayed coffins has fallen away, and . . . crowds of urchins assemble there daily and play with the bones of the dead; troops of hungry dogs prowl about the grounds and carry off skulls and detached parts of human bodies.”

Newspaper articles and editorials suggested that there was something morally improper about leaving so many thousands of bodies exposed for the amusement of urchins and stray dogs, or left to rot in packed trenches, awaiting medical-school body snatchers. When the Board of Aldermen considered purchasing new lands on Ward’s Islands for the expansion of the Potter’s Field in 1852, these scenes were not far from the minds of civic-minded newspaper editors. The Times urged the city “to arrange and adorn” the new Potter’s Field “with suitable shrubbery” so that “if the new grounds are properly laid out, they may be made not only useful but ornamental.” The Times reported that “the new place is to be called the ‘City Cemetery’—so farewell to the old Potter’s Field, a name that is never heard without a thrill of horror.” Frequently throughout the controversial disinterment and relocation of the Potter’s Field in the late 1840s and 1850s, the newspapers referred to the necessity of making both the old and new Potter’s Fields “more proper,” “suitable,” and “respectable,” according to the “dictates of propriety.” But what were these “dictates of propriety?”

The Grave Hath a Voice of Eloquence

In 1858, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine ran an article entitled “Civilization and Health,” which argued that sanitation and “high mental culture” were necessary components to a great democracy. As the individual citizens of the republic might be strengthened by intellectual achievement, so could the social body as a whole be strengthened by a refinement in public health because “the connection of cleanliness with civilization is every where manifest in direct ratio with mental culture.”

The problem of high mortality from disease in New York, however, seemed to indicate that inadequate public sanitation prevented the city from full participation in the progress and benefits of civilization. In 1859, the state of New York issued a special report on the health of New York City in which it acknowledged that mismanagement and lack of sophistication within the city’s sanitation infrastructure were to blame for high mortality. “Great cities are certainly the pride of nations,” reported the investigating committee, “but they require a paternal control, and all Christian and civilized communities recognize the duty of exercising it.” The article from Harper’s agreed that “wherever misery is manifest there always exists at man’s disposal means of mitigating or removing it,” and “to find out and apply these means is advancement in civilization.” Citing the benefits of “the science of public health,” Harper’s proposed that high urban mortality was primarily confined to the poor, but that poverty was not, in and of itself, the cause of death. Rather, “the worst effect of poverty is, that it leads to filth and neglect . . . which affects the whole of the inhabitants.” The civilized solution was “contact with well-cleaned streets and external purity,” which “begets a distaste for internal filth and degradation, and there are none so degraded nor impure as not to be benefited and elevated by association with cleanliness.” Few of Harper’s middle-class readers would disagree.

Of special concern to health reformers in antebellum New York were frequent and devastating epidemics of yellow fever and cholera. While large outbreaks of yellow fever were largely contained by the 1830s, lower class wards remained especially vulnerable to cholera epidemics. Public-health reformers cited numerous causes for these continued public health problems. Slaughterhouses, inadequate sanitation, and urban graveyards were among the most important. Simply put, health reformers assumed that carcasses and cadavers made more carcasses and cadavers.

For this reason, medical science was beginning to call for a new approach to interment. Bodies should lie away from cities, not so much for their own peaceful eternal rest, but for the safety of the living. An 1822 pamphlet entitled Documents and Facts Showing the Fatal Effects of Interment in Populous Cities argued that the pernicious yellow fever epidemics in the city were caused, in part, by the “putrid exhalations arising from grave-yards.” Nearly twenty years earlier in 1806, a committee of the Board of Health had reported that burial in urban churchyards was deleterious to the public health, stating that “interments of dead bodies within the city, ought to be prohibited. A vast mass of decaying animal matter, produced by the superstition of interring dead bodies near the churches . . . is now deposited in many of the most populous parts of the city.”

The committee’s report resulted in an 1813 law granting the corporation of the city the power of “regulating, or if they find necessary, preventing the interment of the dead within the city.” But this power was seldom exercised, and the sudden appearance of yellow-fever epidemics left little time for the healthful burial of the dead. According to Dr. Samuel Akerly of the New York Hospital, the Potter’s Field was already part of this public-health concern in the 1820s and was “known to be frequently offensive, and it sickened a detachment of militia stationed near it in 1814 . . . It becomes the corporation therefore, to prevent its becoming a nuisance, and this may be easily done with quick-lime or ashes of wood.”

Shortly after the publication of the 1822 pamphlet, the Potter’s Field was relocated to the lot at Forty-ninth Street and Fourth Avenue. For the site of the former graveyard, the city followed the suggestion of the 1806 report that “the present burial-grounds might serve extremely well for plantations of grove and forest trees.” The measure was as much about aesthetics as about health. Rather than emanate sickening vapors, a well-planted Potter’s Field would absorb and digest the remaining “putrefying matter and hot-beds of miasmata,” making it at once “useful and ornamental to the city.” From a useless no-man’s land, it would be transformed into a city park and military parade ground, renamed Washington Square.

The city, it turns out, was not opposed to open space—to the contrary, the same impulse behind the drive to push Potter’s Field from Manhattan Island lay behind the drive to create pockets of pastoral delight within the urban grid. Both were part of that antebellum struggle to sustain areas of genteel quietude amidst the city’s bustle and chaos. Among the most popular pastoral retreats for the antebellum middle- and upper-classes were the so-called rural cemeteries, which appeared on the suburban fringes of most American cities between 1830 and 1860. From the vantage of these wooded pleasure grounds, the foul stench of the urban Potter’s Field was particularly offensive.

In a lecture delivered in the 1830s before the Boston Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, Dr. Jacob Bigelow, head of American’s first rural cemetery at Boston’s Mount Auburn, reiterated concerns about the disposal of dead bodies when he observed that “within the bounds of populous and growing cities, interments cannot with propriety take place beyond a limited extent” and suggested that the burial of the dead might better occur “amidst the quiet verdure of the field, under the broad and cheerful light of heaven,—where here the harmonious and ever changing face of nature reminds us, by its resuscitating influences, that to die is but to live again.”

While meeting an urban public-health need, the primary purpose of these rural cemeteries was to contribute to an ongoing discussion about the identity and morality of the nation, quite literally embodied in the illustrious dead. Visitors to rural cemeteries were expected to lose themselves in the harmonies of creation as they contemplated the noble biographies of the departed. In their pastoral classrooms, the illustrious dead were teachers of history and morality, and their timeless presence in such institutional places of rest affirmed the permanence of not only the local community but the national community as well.

For the greater New York metropolitan area, the principal rural cemetery was Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, established in 1842. In advocating for its creation, newspapers, health reformers, and city-park enthusiasts reiterated many of the same assertions about public health and morality that had circulated in the city since the 1820s. Green-Wood quickly became famous, with its three hundred acres traversed with fifteen miles of garden pathways. Phelps’ New York City Guide for 1857 described Green-Wood as “one of the most interesting objects of public utility and beauty near New York” and “a favorite rural resort during the summer season” as well as “a holy spot [which] links itself to our being, with a cherished fondness and satisfaction.” Until the completion of Central Park in the 1860s, Green-Wood Cemetery was New York’s primary garden spot.

Having strolled through the rural cemeteries, we can better appreciate why the piles of moldering coffins exposed to the public in the 1850s caused New Yorkers to question their city’s claims to “civilization.” But the Potter’s Field was not only the antithesis of the rural-cemetery ideal (as well as a failure of municipal administration); it was also a site of spiritual death, obliterated social identity, and the graveyard of vice. If, as one proponent of rural cemeteries claimed in 1831, “the grave hath a voice of eloquence,” the Potter’s Field spoke in a dark chorus about the failures of democracy and civilization, the stark and messy exigencies of urban inequality, and thousands of individual lives wrecked on the shores of the great metropolis.

In The Common Dust

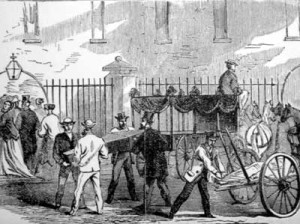

In May of 1858, a little-known author named Henry Herbert contemplated and ultimately committed suicide. Before his death, he pleaded to his friend Miles I’anson, “I must not be buried in the Potter’s field, or by charity.” Several days later, when John Aikins, second mate of the ship Mandarin, was killed by a sailor in a fight, Captain Dubois of the California clipper Queen of the Pacific (who only had a passing acquaintance with Aikins) personally took on the cost of a casket and a plot at Green-Wood Cemetery. He could not bear the thought of a fellow officer being taken to Potter’s Field. Similarly, when an elderly man was found “in a fit” on a dock near Washington Market and subsequently died at a police station house, preparations were made to inter the body in Potter’s Field. But at the last minute the body was recognized as a “man of some prominence” by a Brooklyn scientist, who “requested that the body might be given to him for decent burial” in his own plot at Green-Wood. In each of these cases, the deceased either expressed or was saved by a fervid desire to avoid the humiliation and anonymity of a pauper’s burial, which would have signified a fall from the bourgeois society of which they had once been a part. To bury these people in the Potter’s Field would have been an unconscionable breach of propriety.

The sorts of people for whom a Potter’s Field burial was considered acceptable by benevolent institutions and reformers ranged widely from newborn infants abandoned on street corners to inebriates and “fallen” women. These burials were reported with parsimony by New York’s newspapers:

“October 20, 1852: The body of an unknown lad was found yesterday floating in the East River off Burling-slip. The deceased was not recognized, and, upon the Coroner holding an inquest, the body was sent to Potter’s Field for interment.

February 04, 1858: Rosa was 19 years of age. She formerly boarded at a lager-bier saloon at No. 257 William-street, and has for nearly a year past borne a questionable character. No one has thus come forward to claim the body, and it is probable she will be buried in Potter’s Field.”

If it was true, as one reformer claimed in 1854, that “many a saddening pang afflic’s the last moments of the children of poverty, upon reflecting that their remains must moulder in the common dust of Potter’s Field,” tens of thousands of the city’s poor lived in fear of an eternity spent in anonymity. Likewise, middle-class New Yorkers used the possibility of a Potter’s Field burial as a kind of moral barometer. One can easily imagine parlor gatherings attended by much clucking of tongues over the most recent rumor that if Mr. So-and-so continued in his intemperate ways, a pauper’s grave would provide his final rest.

The moral horror of a pauper’s grave was not just an expression of simple Victorian propriety or Protestant death-ways. It also derived from the simple visibility of the Potter’s Field. There was no privacy in a pauper’s death; your bones, like so many family jewels, were exposed to all of the city’s most pernicious impulses. In imagining the horrors of a pauper’s burial, middle-class Americans drew a line between themselves and what Jacob Riis would later refer to as the “other half.” Rural cemeteries like Mount Auburn and Green-Wood were idealized by bourgeois urbanites as didactic landscapes, but the Potter’s Field as both a physical place and a cultural symbol was also imbued with instructional possibilities. It warned that the expected fate of the intemperate, the immoral, and the fallen was a gruesome eternal repose. Antebellum New Yorkers wanted to be frightened and disgusted by the Potter’s Field because it provided a startling moral corrective. Despite their cries for reform, they still expected to find the paupers’ burial ground disgusting and degrading and terrifying because they expected that its occupants, in life, had been the same. When this expectation abutted the very real public-health concern, linked as it was with the language of civilization, middle-class New Yorkers reacted within the expectations of their class: they were properly horrified but took only a limited interest in actual reform. As middle-class New Yorkers began leaving the city at midcentury, the need for such symbols of moral suasion diminished. Potter’s Field could now lie quietly isolated by the slow moving waters of the East River.

Further Reading:

For the role of dead bodies in nineteenth-century medical, anatomical, and cultural discourse, see Michael Sappol’s A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America(Princeton, 2002), which contains a brief section on the Potter’s Field and its obliteration of social identity; for the development of a health-based idea of propriety and nationalism, see Joan Burbick, Healing the Republic: The Language of Health and the Culture of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century America (Cambridge, 1994); and for the didactic role of the city park and the rural cemetery in nineteenth-century urban planning, see David Schuyler, The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore, 1986).

This article originally appeared in issue 6.4 (July, 2006).

Thomas Bahde is a doctoral candidate in U.S. history at the University of Chicago. He is currently writing a dissertation using microhistorical and biographical methods to examine issues of race and justice in the nineteenth-century Midwest.