Historians who teach the War of 1812 often end their lecture by explaining that amid the smoldering ruins of a capital that had been burned in August 1814, many Americans ignored more than two years of military disasters, and the fact that the peace agreement settled none of the issues that led to the war, by proclaiming victory. A victory made all the more plausible by an odd coincidence of news reporting: on February 4, 1815, word arrived in Washington, D.C., of Andrew Jackson’s defeat of the British at New Orleans; ten days later the Treaty of Ghent appeared, bringing the war to an end. Although the two events were unrelated, with Jackson’s triumph (January 8, 1815) occurring after the peace accord at Ghent (December 24, 1814), historians like to assert that the events were connected in the popular mind. As I have announced in many a lecture hall: one headline read “JACKSON VICTORY AT NEW ORLEANS,” and the other “PEACE SIGNED WITH THE BRITISH.”

Such fabricated headlines may be great in the classroom. But they obscure a more complicated story. The supposed victory in the war was not so clear to the people who lived in 1815. For many Americans, and not just the arch Federalists who had all along opposed fighting the British, the treaty did not speak to the war’s root causes. It failed to address free trade, America’s ability to trade unhindered by British restrictions. Nor did it protect American sailors from impressment. The problematic nature of the treaty came into bold relief in late spring and early summer in the wake of the tragedy that became known as the Dartmoor Massacre.

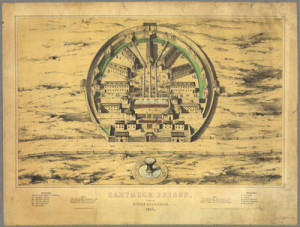

Dartmoor is a fogbound corner of southwest England, perhaps best known as the setting of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mystery The Hound of the Baskervilles. It is just the kind of place where it is possible to believe that a large, primeval, supernatural beast could wreak havoc. When the shroud of mist lifts, Dartmoor can be starkly beautiful. More often the weather is oppressive and the countryside nearly invisible. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British selected the site for a prison to house the French sailors and soldiers they captured, locating the compound just far enough inland to keep it safe from raiders hoping to liberate their comrades, but close enough to Plymouth to make it a day’s march from the coast. The prison, constructed with a huge circular wall around it, was erected in a valley, increasing the likelihood of fog. The strategy worked. When I visited the region one early spring day in 2006, the combination of low-hanging clouds, mist, and rain, made it almost impossible to see the gate as I drove by. (The building is still used as a prison.)

During the War of 1812, Dartmoor gradually became a prison for Americans. Initially, the British lodged Americans captured on the high seas at Dartmoor with the French. As conflict with France wound down, French prisoners were sent home across the channel. And, as the British captured an increasing number of American ships, more and more Americans were concentrated in the compound. The British even sent men who had been serving in the royal navy, and who claimed American citizenship, to Dartmoor. Many of these sailors had been impressed and resented the way they were being treated now that His Majesty’s Navy no longer needed them to fight Bonaparte’s navy. By the end of 1814, there were 6,000 Americans in Dartmoor, about one fourth of whom had been released to the prison from the British navy, while the rest had been captured at sea.

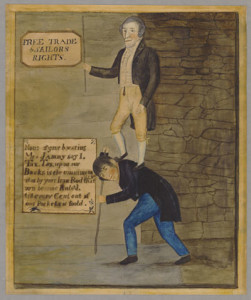

Between the signing of the Treaty of Ghent and April 6, 1815, the day of the incident the Americans called the Dartmoor Massacre, the prison on the desolate moor was fraught with tension. As soon as the American prisoners heard of the treaty in December, they ran up a banner announcing “free trade and sailors’ rights,” using the slogan that had been ubiquitous in the United States and was an accepted shorthand for the causes of the war. The prison commandant found the slogan so offensive that he insisted that the banner be taken down. After tense negotiations, the prisoners agreed to remove their standard for the time being, and the commandant promised to fly both the British and the American flags atop the prison. In the weeks and months that followed, the prisoners tested their British guards at every opportunity. They tried American agent Reuben Beasley in effigy for not alleviating their harsh conditions. Finding him guilty, the prisoners then hanged his effigy. Later they rioted over the type of bread served.

As a bleak and miserable winter gave way to a bleak and miserable spring, the prisoners began to wonder why, if there really was a peace, they had not been exchanged. They had reason to be concerned. The Treaty of Ghent had stipulated that “All Prisoners of war taken on either side as well by land as by sea shall be restored as soon as practicable after the Ratifications of this Treaty.” The difficulty was what was “practicable.” It was easy enough for the Americans to return British prisoners to Canada or some other nearby British possession, but the expense of sending the prisoners in England across the Atlantic proved to be a stumbling block. As the British and Americans dithered over who was to pay this extra cost, the sailors in Dartmoor watched one cold and bleak day blur into the next. With many of the prisoners sick and malnourished, discontent soared. Then in March, smallpox broke out in Dartmoor, leading to additional deaths and further delays.

This was the background for the massacre. The sixth of April was one of the first nice days that spring, and the prisoners amused themselves playing ball or lolling about in the unusual sunshine. Toward the end of the day, some of the Americans repeatedly tossed a ball over the wall and called upon a guard to retrieve it. When the British soldier tired of what was turning into a game of fetch, he told the prisoners to go get the ball themselves if it went over the wall again. Soon enough, the ball was over the wall, and heeding the soldier’s advice, the sailors began to break a hole through the wall. This small confrontation soon escalated and the British guard rang the warning bell for the sailors to return to their prison buildings. When the Americans rushed the gate instead, the situation turned serious. The commandant ordered the prisoners back at the point of bayonets. The sailors tossed dirt and rocks at the soldiers. A shot rang out from the British ranks, followed by other shots from soldiers on the wall. The Americans ran back to their buildings amid a hail of bullets. The shooting continued for twenty minutes and left six dead and over sixty wounded.

Lord Castlereagh, the British foreign minister, recognized that the events at Dartmoor jeopardized relations with the United States. A quick military inquest at Dartmoor exonerated the British commandant and blamed the violence on the prisoners. This report, Castlereagh knew, only made matters worse. What was needed was a more neutral investigation with American involvement. He turned to Henry Clay and Albert Gallatin, who had arrived in London after completing the Ghent negotiations to discuss a commercial agreement, and asked them to travel to Dartmoor with one of the British representatives who had been at Ghent to investigate the affair and draw up a report. These two Republican politicians refused to go anywhere near the inquest, no doubt believing that a report that did not condemn the British would be political suicide in the United States. They recommended sending Reuben Beasley, lately tried in effigy, who claimed he was too busy arranging transport for the prisoners to leave London. Ultimately, Clay and Gallatin convinced Richard King, who happened to be in London on personal business and was the son of Federalist leader Rufus King, to travel to Dartmoor. Joined by an English lawyer named Francis Seymour Larpent, King interviewed all sides at Dartmoor and wrote a balanced report blaming both the sailor prisoners and the British soldiers, but not the commandant.

If Clay and Gallatin refused to go to Dartmoor for political reasons, they were right. News of the so-called massacre created a firestorm in the United States. Information traveled slowly across the Atlantic, but by late May word of the incident drifted into American ports. Vague and unsubstantiated, these first reports merely indicated that there had been some sort of riot at Dartmoor and reflected what had appeared in British newspapers. However, after months of delay, both the British and the Americans wanted to empty Dartmoor as quickly as possible after the massacre, and the American prisoners of war soon began to arrive from England. Outraged by their treatment as prisoners, these sailors viewed the events of the sixth of April as a preconcerted atrocity exacted as vengeance for Jackson’s victory at New Orleans and the American “triumph” in the war. Republican editors rushed the prisoners’ stories into print, filling their columns with first-person accounts, and publishing memoirs and even selling prints depicting the prison and its massacre. The sailors dismissed the King-Larpent report as a whitewash and issued their own report that declared that the commandant had ordered his men to fire. When the official report became public in the United States in mid July, Republican editors joined in the chorus attacking King and Larpent. As one editor noted: The inquiry was “of too high import to be settled between young Mr. King, and an unknown British lawyer; for if sailors’ rights are worthy of the consideration of government, sailors’ blood is a subject of equal magnitude.”

Federalists at first reacted cautiously to the news of Dartmoor, asking the public to hold off on its judgment until all the facts were known. For them, the King-Larpent report confirmed their faith in the British who had been willing to compromise. In response to the Republican attacks on Richard King, a few Federalists wondered out loud why such talented men as Clay, one of the most gifted lawyers in the land, and Gallatin, an experienced diplomat, had refused to go to Dartmoor and left such a delicate task to an inexperienced private citizen who then became their “scapegoat.”

Whatever the fulminations of Republican editors and the exclamations of perfidy by so many returning sailors, the Madison administration did not want the Dartmoor Massacre to lead to a break in relations with the British. Certainly, there was no way the nation would return to war. Clay and Gallatin, and then joined by John Quincy Adams, had completed their commercial negotiations with the Convention of 1815. This landmark agreement provided for the reciprocal trade that had been the goal of American diplomacy since 1776. Hereafter, the British and Americans would treat each other’s merchants, in terms of imposts and shipping duties, the same as they treated their own merchants. Neither nation wanted a few dead and wounded sailors to get in the way of the promise of free trade and open commercial relations.

Common folk saw things differently. Dartmoor became etched in popular memory, reflecting the image of a nefarious, inimical, and perfidious enemy—the detested British. In short, a war that had been painted in such triumphant colors early in 1815 had by the same summer come to include a dark streak—a deep scar on the popular consciousness. American historians often overlook that scar. Examining the end of the war within its international context and viewing events on both sides of the Atlantic allows a more balanced assessment. Sailors’ rights remained violated by both the treaty of peace and the Dartmoor Massacre. For many Americans, whatever the assertions of the Madison administration, the so-called victory was tainted and incomplete.

Further reading:

In addition to Paul Gilje’s forthcoming Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights in the War of 1812, you can read more about Dartmoor in his Liberty on the Waterfront: American Maritime Culture in the Age of Revolution (Philadelphia, 2004) and in Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, Mass., 1997). For a standard account of the diplomacy at the end of the war see Bradford Perkins, Castlereagh and Adams: England and the United States, 1812-1823 (Berkeley, Calif., 1964).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.4 (July, 2012).

Paul A. Gilje, the George Lynn Cross Research Professor in History at the University of Oklahoma, writes on the American Revolution and the early republic. Material from this essay was drawn from his new book, Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights in the War of 1812, which will be published by Cambridge University Press this fall.