Bill opens his long coat. Inside, from a leather belt, hang a cleaver, knives, and other butcher’s instruments. Bill selects his weapons, a cleaver and a big knife.

Bill the Butcher By the ancient laws of combat, we are met on my challenge to reclaim the Five Points for them born rightwise to this land, from the foreign invader who’s encroached upon our streets. The last time we met I was shamed! But in shame or glory, we won’t never rest until last of him’s been drove into the sea!

The Natives shake their weapons and roar.

Priest Vallon By the ancient laws of combat, I accept the challenge of the so-called Natives, who plague our people at every turn. We seek no quarrel, but will run from none neither, and the hand that tries to lay us low will be swift cut off!

The roaring is deafening. Every weapon is hoisted and bristling. Smoke rises from the beard of the man who dusted it with gunpowder.

This excerpt from the shooting script of Gangs of New York, Martin Scorsese’s Academy Award-nominated film about mid-nineteenth-century urban poverty, politics, and crime, describes the drama’s opening scene: rival Irish and nativist gangs are poised to do battle to decide who will control the infamous Five Points slum district of lower Manhattan. But it could just as accurately describe the recent confrontation between the film’s critics and its fans. Since Gangs‘ release in December 2002, an unbridgeable gulf has formed between the kudos of many film reviewers and the more subdued but negative response of historians. In the marketplace of opinion—not to mention hype—one would suppose that few care about what historians think. But in a mode similar to, if less sanguinary than, the behavior displayed by the film’s knife- and cleaver-wielding characters, historians have been challenged to accept the film on its own terms. After declaring that Gangs of New York was “historical filmmaking without the balm of right-thinking ideology, either liberal or conservative,” A. O. Scott in his passionate New York Times review threw down the gauntlet: “People who care about American history, professionally and otherwise, will no doubt weigh in on the accuracy of its particulars and the validity of its interpretation; they will also, I hope, revisit some of their own suppositions in light of its unsparing and uncompromised imagining of the past.” Historians’ criticisms have been met with the familiar, condescending refrain to lighten up: it’s only a movie. But, despite the pessimistic predictions of movie industry observers, the film is likely to end up the most commercially successful work in Martin Scorsese’s long but not very lucrative career. Its recent nomination for ten Academy awards guarantees its screening for at least a few more months. And now that it has revealed the shapely legs of box-office persistence, and perhaps because it depicts a time and subject that few people have heard of, it has gained a good deal of legitimacy. If the many questions directed to a New York City history Website I co-supervise are any indication—including a certain befuddlement by visitors when they fail to locate information about events wholly invented in the film—audiences believe its story. It’s worth asking exactly what that story purports to tell. Gangs of New York is certainly unusual in focusing on the city and its “netherworld” during the Civil War. The film’s inspiration is Herbert Asbury’s 1928 compendium of urban myths, The Gangs of New York, the narrative epicenter of which is the Five Points, the intersection of three streets that was the symbolic heart of one of the poorest city neighborhoods in nineteenth-century America. Covering the 1830s to the 1920s, Asbury’s popular and highly unreliable account depicts decade after decade of lawlessness, corruption, and violence embodied and carried out by a host of colorful, brutish, and often Irish characters. Scorsese’s Gangs has a narrower range, homing in on 1862-63 (after an introductory bloodletting in 1846), grafting onto the mayhem a number of thinly-portrayed historical figures and a worn-out revenge story. That predictable tale involves young Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) who returns to the Five Points to avenge the murder of his father, the leader of the vanquished Irish Dead Rabbit gang, at the hand of the nativist demagogue Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis in the role usually played by Joe Pesci). As numerous historians have pointed out in interviews and articles, very little in Gangs of New York‘s litany of gang warfare, political and police corruption, public hangings, assassination, Catholicism, and gender and race relations is accurate. And, with the exception of the film’s climactic event, the July 1863 Draft Riots, the numerous murders of cops, politicians, the public display of victims and prostrate corpses—they all bear no consequences: New York was the anarchic eastern frontier and its Dodge City was ruled by a mercurial, racist, nativist dictator. It will come as no surprise that, in the end, Bill gets his comeuppance, amidst a naval bombardment of the Five Points that never happened.

This production’s misrepresentations could be filed away as yet more instances of Hollywood obliviousness to historical scholarship and reliance on familiar plot devices that audiences supposedly favor. That disappointing but predictable formula might be a little less unsettling if Gangs of New York did not try to re-imagine a place and era whose meaning and substance have been almost entirely redefined over the last quarter century. Beginning with Carol Groneman’s groundbreaking “The ‘Bloody Ould Sixth'” (Ph.D. diss., U. of Rochester, 1973), continuing through studies by historians such as Christine Stansell, Peter Buckley, Richard Stott, Iver Bernstein, and up to Tyler Anbinder’s meticulous, 2001 Five Points, (not to mention Mike Wallace and Ted Burrows’ Pulitzer-prize magnum opus, Gotham), New York historians have discarded the “sunshine and shadow” lens through which nineteenth-century urban society was previously viewed. In contrast to the Five Points depicted in Gangs of New York, the real neighborhood was more notorious for its congestion, disease, alcoholism, and prostitution than for violent crime (the whole city in the mid-1850s averaged about thirty murders a year). Death was more likely to come from contagious diseases that swept through the close, crowded, dark, and damp tenement compartments (claiming one out of three children under the age of five) or from work-related accidents. Indeed, neither homes nor labor seem to play any part in Scorsese’s Five Points (either for men or women, unless in the latter case, petty crime qualifies), which is particularly striking since the gangs that inspired the film arose as a result of the transformation of work. As the customary moral, educational, and supervisory relations between urban master craftsmen and their journeymen and apprentices crumbled at the close of the eighteenth century, young mechanics took to gathering into loose associations after work hours. Identifying themselves by neighborhood, street, and especially trade, the number of these gangs proliferated in the Jacksonian era, their allegiances often merging with other manly and occasionally violent voluntary associations such as fire, target, and militia companies. For many young men the gangs symbolized resistance to an encroaching world of permanent wage labor. Looking back from the 1880s, Richard Trevellick, a leader of the Gilded Age’s largest labor organization, the Knights of Labor, recalled, “[W]ith us in New York, boy or man, we were rather proud to be known as one of the infamous ‘Chichester Gang,’ ‘Sons of Harmony,’ or a ‘Butt-Ender.’ Philadelphia mechanics of that day . . . knew no more coveted distinction than that of a ‘Killer’ or ‘Moyamensing Ranger.’ While Baltimoreans were prouder of the titles of ‘plug uglies,’ ‘blood-tubs’ and ‘roughs’ . . . than they were of being good citizens or skillful mechanics.” “Grassroots” politics, especially in New York, became a particular preoccupation of these usually short-lived and only nominally criminal organizations. In the downtown wards of the city, political power in the local Democratic Party was determined in struggles among factional leaders and their followers. As the Irish made inroads into the nativist-controlled ranks of the party, primaries and elections were often decided by which faction brought the most and toughest fighters. Brickbats, clubs, and fists, the standard weaponry in a fight, could do a lot of damage, but fatalities were not frequent until mid-century with the manufacture and distribution of cheap handguns. The twelve deaths and thirty-seven or so injuries that occurred during the so-called Dead Rabbit-Bowery Boy Riot in the Five Points on July 4, 1857, was so extraordinarily high—and attracted so much attention—because of the use of guns. The cleavers, axes, maces, and other imaginative implements wielded, wedged, and jabbed in Gangs of New York‘s street fights, and the ensuing mutilations and massive body counts, misrepresent the extent and nature of antebellum gang violence. They also overawe the truly horrendous bloodshed during the 1863 Draft Riots. In the end, Gangs of New York‘s violence only perpetuates the belief that, for the poor, life is cheap.

Preoccupation with verisimilitude may be an occupational hazard among historians (for example, I cannot suppress my urge to note that the Dead Rabbits gang did not exist, but instead was the tough and exotic name—possibly derived from street slang in turn influenced by the Gaelic phrase “dod raibead,” meaning an “athletic, rowdy fellow”—that reporters and police labeled a local Five Points gang after the 1857 riot). But as historians should be the first to concede, facts and history are not interchangeable notions. Moreover, dramatic license and telescoping events are but two facets in any film’s vision of the past that we should evaluate with an eye to both the medium and the message. As A. O. Scott observed in his paean to the film, Gangs of New York is unusual in shunning “the usual triumphalist story of moral progress and enlightenment,” instead offering a vision of the modern world arriving “in the form of a line of soldiers firing into a crowd.” Scorsese’s vision does include a class-ridden society, its elites cruelly inured to want, its exploited subaltern classes feeding on one another. But this vision is a variation on themes many historians have rejected or substantially revised in recent scholarship. With certain exceptions (its references to the African American presence in the Points and unequivocally horrified view of racism—in contrast to the film’s utterly stereotyped portrayal of the Chinese), Gangs of New York could have been made forty years ago (okay, thirty-three years ago if we allow for its post-Peckinpah blood). Even taking into account its class consciousness and the occasional sympathy it extends to the Irish in their abjectness, Gangs of New York‘s emphasis on a degraded, criminal underclass with a brogue fits the sunshine-and-shadow social paradigm espoused by the type of antebellum reformers that the film shows bumbling ineffectually about the Points. In short, it’s a profoundly anti-urban film, a historical version of the dystopian fantasies of the 1970s and 80s such as Escape from New York, Assault on Precinct 13, and The Warriors. If the film adulates anything, it’s old movies about New York: various scenes pay homage to, their very premises lifted from, classic if now obscure films about the nineteenth-century city, particularly Raoul Walsh’s The Bowery (1933) and Gentleman Jim (1942).

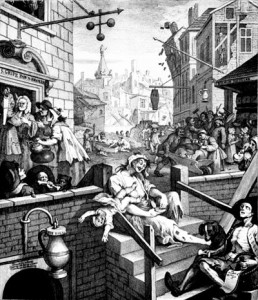

If some have been dismayed by Gangs of New York‘s approach to the historical record, the film’s production design, supervised by Dante Ferretti, has received almost universal acclamation; for those less enamored of the rest of the saga, the sets succeed in enveloping and anchoring a flawed story in a convincingly detailed physical world. The palpable centerpiece, the already legendary vast Five Points set constructed on the grounds of the Cinecittà studios in Rome, is indeed stunning to behold. And for those familiar with the engravings, lithographs, and fewer photographs of the nineteenth-century Five Points, there is a host of entertaining visual quotes throughout the film (Exhibit C). The visual record of the Five Points and urban poverty in general (examples of which are arrayed about this page) is at best contingent, fractured by sporadic documentation and not a little imagination. Scorsese and his team immersed themselves in the archives and it shows—as does his failure to address these images with any judgement or criticism. Taking the moral narratives of reform tract engravings and their British inspirations (notably William Hogarth’s wildly allegorical Beer Street and Gin Lane prints) at face value as sources for his visualization of urban poverty, Scorsese’s resurrected Five Points landscape is populated by an almost constant charivari of the grotesque and wretched—leering prostitutes, preening bullyboys, stiffened corpses, and scampering children. Alternatively, the interiors (the repertoire is surprisingly limited) are seemingly inspired by Gustav Dore’s prints of London: the infamous rabbit-warrenlike Old Brewery (torn down by the Methodist Five Points Mission in 1852) is imagined as a multi-tiered cavern with the added feature of underground tunnels replete with piles of skulls. In these visual terms, Gangs of New York is to Civil War Manhattan what Fellini’s Satyricon is to Nero’s Rome—with a pinch of straight-faced Monty Python filth added to the faces and clothes. Expressionism is a compelling visual strategy, epitomized in the Italian master’s excessive sets, which operated in harmony with the performances he elicited and the stories he told. In contrast, Scorsese’s production design, enveloping exposition-heavy dialogue and (with the exception of Daniel Day-Lewis) pedestrian performances, may be (as he has proposed) truer to opera but it conveys to audiences documentary. “The Five Points,” the New York Tribune remarked in June 1850, “is the scene of more monstrous stories (at a distance) than any other spot in America; and yet it is not such an awful spot, after all.” Horace Greeley, the newspaper’s editor, is a bumbling cardboard-thin character in the film. One hundred and fifty-two years later, one wishes Gangs of New York had heeded his advice.

Further Reading: Tyler Anbinder’s Five Points: The 19th-century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum (New York, 2001) is the most recent and comprehensive history of the neighborhood and its people; for the Civil War in New York, see Edwin G. Burrows and Michael Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York, 1999) and Edward K. Spann, Gotham at War: New York City, 1860-1865 (New York, 2002), and Virtual New York City, which includes the most comprehensive online history of the 1863 Draft Riots. For informative critical commentary on Gangs of New York, see: Maureen Dezell, “Film Captures the Feeling But Not the Facts of Life in Five Points,” Boston Globe, December 20, 2002; Pete Hamill, “Trampling City’s History: ‘Gangs’ Misses Point of Five Points,” New York Daily News, December 14, 2002; Robert W. Snyder, “Gangs of New York Gets New York City Wrong,” openDemocracy, January 15, 2003; “History Lesson: Author and Civil War-era Expert Iver Bernstein on the Inaccuracies in Martin Scorsese’s ‘Gangs of New York,'” Newsweek.Com, January 10, 2003; Daniel Czitrom, “Gangs of New York,” Labor History (forthcoming); and Joshua Brown, “The Bloody Sixth: The Real Gangs of New York,” London Review of Books, 25:2 (January 23, 2002).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.3 (April, 2003).

Joshua Brown is executive director of the American Social History Project at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. He is the author of Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley, 2002).