Rudolf Cronau did many things. He wrote a multi-volume account of Christopher Columbus, which identified the explorer’s final resting place and won an award at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. He wrote a striking book on the history of advertising, another on environmental degradation in the United States, a multi-volume account of Germans’ contributions to American history, and a scathing portrait of British imperialism. As an American citizen, he took up an avidly anti-British position as World War I broke out, saw his book on British imperialism impounded by the American courts, was active along with his wife in war relief efforts for Germany, and died in 1939 thinking that Adolf Hitler might indeed restore Germany to its former glory. He is most well known in Germany, however, for the trips he took to the United States as a correspondent and artist for the German illustrated magazine Die Gartenlaube during the last two decades of the nineteenth century—especially for his 1881 trip to the Dakota territory, where he met Crow King, Gall, Hump, Rain in the Face, Sitting Bull and other famous American Indians. During that visit, he recognized an affinity with these people that had become common among Germans long before his journey, and which persists among them to this day. In that way, he channeled one of the most fundamental elements in the German love affair with American Indians.

The widespread fascination with American Indians among Germans began with a triumvirate: Cornelius Tacitus, Alexander von Humboldt, and James Fenimore Cooper. When the Roman Senator Tacitus wrote Germania during the first century CE, he portrayed Germans as a noble tribal people with an existential connection to the forests and lands of Central Europe, who suffered at the hands of an expansive, colonial civilization. Indeed, he wrote about Germans much in the same way German authors would later write about American Indians, as noble savages and formidable, violent warriors with painted faces, living in forest dwellings, whose most honorable qualities exposed the decadence and failings of the civilized world.

Like many Germans who later wrote about American Indians during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Tacitus got many things wrong. Those errors, however, matter less than the fact that his work became an influential point of reference for a range of Germans seeking to better understand themselves and their place in the world. Tacitus’s portraits of tribal Germans as fearless, honest, unflinching, loyal, and physically powerful made comparisons to American Indians natural. Already in the seventeenth century, for example, German writers conflated the ancient Teutons portrayed by Tacitus with contemporary American Indians, and by the middle of the nineteenth century such comparisons circulated widely.

Indeed, between 1809 and 1900 at least seventy-two publications were devoted to the battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE, when the hero Arminius or Hermann defeated the Romans. These texts made it clear that by the mid-nineteenth century, Germans had developed a sense of pride in that history which, in turn, provided them with an easy sense of affinity toward American Indians.

At the same time, Alexander von Humboldt’s well-heralded travels in Central and South America around the turn of the nineteenth century provided the German literate classes with a model of erudition and Bildung (essentially self-edification) that inspired many to take the new world seriously. Indeed, Bildung, a common goal among such people at the outset of the nineteenth century, combined well with the prevalent sense of Germans’ destiny as a conglomerate of tribal peoples. In many cases, in fact, it was the effort at gaining Bildung that led many Germans to read Tacitus in the first place, and then encouraged them to seek out other means of exploring the German past.

Moreover, if Tacitus provided Germans with a historical link between themselves and American Indians, and Humboldt offered an example for how to engage them, it was unquestionably James Fenimore Cooper who completed this triangle of origins by inspiring Germans’ imaginations with his finely crafted tales. Cooper was easily the most translated American author in Germany, and through the countless reproductions of Cooper’s novels, the German fascination with American Indians became heightened and widespread (fig. 1).

What followed, then, during the first decades of the nineteenth century was a remarkable surge of inspiration and efforts at emulation, which spurred Germans to travel like Humboldt, to write like Cooper, and to seek out the tribal peoples of North America who had not yet succumbed to the fate of their own European ancestors. Indeed, a series of German travel writers and novelists built on the success of those stories. By writing about American Indians, they, like Cronau, became best-selling authors over the rest of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. The most prominent of these was Karl May, whose books sold over 70 million copies by the 1980s, about 20 million more than the most well-known American author of westerns, Louis L’Amour.

Such successes seem astonishing until we recognize that by the turn of the twentieth century, thinking about American Indians had become integral to German culture. Indians were not only a popular subject among novelists and other writers, they were incorporated into the production of toys, theater, circus, high and low art, and the new cinema. Across Imperial, Weimar, and later Nazi Germany, children of all ages and both genders “played Indian,” emulating the characters from Cooper and May and the people they encountered in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and German circuses.

Adults “played Indian” as well, and not simply those individuals who joined the first hobby clubs in the early twentieth century or continued this pursuit in the postwar era. Modernist artists like Georg Grosz, Otto Dix, and Rudolf Schlichter, for example, turned to their childhood engagement with American Indians while dealing with their personal crises and the crises of modernity. Art historian Aby Warburg traveled to the Hopi and Zuni pueblos for the same reason; the artist Max Ernst, the psychiatrist Carl Jung, and ethnologists Karl von den Steinen and Paul Ehrenreich followed. Adolf Hitler remained in Germany; but he continued to read Karl May’s Winnetou for insights into crisis situations, recommending it to his General Staff during the battles of World War II.

“Indians,” in short, became deeply ingrained in German culture during the nineteenth century, their stories became ciphers for modern struggles during the twentieth century, and that long cultural history continued unabated through the postwar era, resurfacing during Cold War clashes, peace protests, environmental movements, esoteric musings, visits of postwar German tourists to American Indian reservations, and the persistent settings of backyard play and hobbyists’ camps where, in every performed conflict, the “Indians” remain “the good guys.”

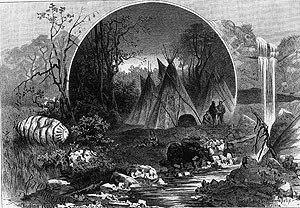

Cronau’s revelations during his 1881 stay among the Lakota capture the essence of this appeal, which, by the time of his adventures, was almost overdetermined (fig. 2).

Cronau’s vision

Rudolf Cronau was born in 1855 into a civil servant’s family in Solingen, a small Rhineland town just north of Cologne. He saw little of his father, who died when Cronau was ten, and his mother left him an orphan just two years later. Shuffled from one relative’s home to the next, as each in turn passed away, Cronau was increasingly isolated: His half-brother and half-sister left him behind as each sought their fortunes in America, and his sister Anna married and departed to Barmen in 1870. Afterwards, he lived alone with their aunt until he too, at the age of fifteen, set off to attend the famous Düsseldorf Academy of Art.

He did not stay long. Chafing under his mentors’ strong Catholicism, their focus on religious themes, and their insistence that he reproduce images from classical art, he left the academy, sought adventure in the Franco-Prussian War, and returned to Solingen to work as a journalist while pursuing his passion: landscapes. He produced drawings of the Harz Mountains, the Sächsisches Schweiz, the Riesengebirge, the valleys of the Elbe and Oder Rivers, and other picturesque parts of Germany and Austria. He was talented. He became a regular contributor to Die Gartenlaube by the mid 1870s, moved to Leipzig and joined the city’s Art Association, and eventually became its chairman before gaining a commission to travel to the kinds of “wonders” that dwarfed the landscapes he had seen in Europe: the geysers in Yellowstone, the walls of El Capitan in Yosemite Valley, the vast prairies, and the modern spectacle of American cities.

When Cronau crossed the Atlantic in January 1881, he filled his notebook with details from his shipboard adventures. His notes on passengers, sea sickness, and the ship’s emergency preparations were quickly overshadowed, however, by his excited first glimpse of the lighthouse on Fire Island, the quickening sensation that came with the early morning murmurs of land, and his impressions of their arrival in New York harbor. On entering the city, however, those reports gave way to silence. It took time to comprehend the wonder of New York—many days passed before he began recording it.

When he returned to writing, he focused on the city’s aesthetic, which he discerned in the chaos and order of the city’s architecture, the rhythm of its streets, and the purposefulness of its people. He described New York’s harbor as a criss-crossing collection of ship’s masts and towers, a throng of colorful confusion. His experience of the port was a mixture of quick images, of even quicker English, smatterings of various German dialects, and above all, incessant movement. The difference between “the homeland,” he explained, “is shocking; every step, every movement into the streets, brings something new and stimulating.” “Everything is interesting,” he wrote, “even if not all is satisfying. The construction of the houses, the deep red of the bricks, the chocolate color of the brown stone palaces, the number of colorful announcement boards,” give the streets such a “special complexion” that one never tires of acting the flaneur.

While much of what he witnessed was wondrous, not everything was unfamiliar. This too is critical: America was full of Germans. Indeed, when Cronau arrived in New York City, his stepsister Mathilde Waldeck Stöcker greeted him on the docks and took him into her home. From that comfortable setting, he became acquainted with the city’s German community. After only a few days in town, he met the editors of the New-York-Staatszeitung, one of the largest German-language newspapers in the world, initiating a relationship that would continue until the last years of his life. Through them, he gained introductions to many prominent people: members of the German art community, scientific associations, politicians, and eventually Karl Schurz, a fellow Rhinelander and the United States Secretary of the Interior. It was Schurz who approved Cronau’s idea to travel to Dakota territory in order to capture the moment in which America’s most formidable warriors settled onto its last reservations. And as he traveled there, he moved across vast German-American networks.

Sublime landscapes and emotional projections

Cronau left for the American West in May 1881. Traveling by train across the upper Midwest, Cronau saw endless woodlands broken by occasional villages, by zealously cultivated farmland, and by burgeoning Midwestern cities and towns. The distances were daunting. The trees in American forests seemed to grow more densely than in Germany, “everything,” he noted, “struggling up towards the sky.” The rolling landscape had a certain appeal, and he collected images, clipped from newspapers and magazines, in his diary. What most impressed Cronau on his journey to St. Paul, Minnesota, however, was the spectacle of Niagara Falls.

Niagara brought him face to face with the natural sublime he expected to find in America, the antinomy to the cityscapes, and it evoked in him the essential longings that inspired his trip. Staring out at the falls from Prospect Point he saw a vision “like that which had filled my fantasies since my early youth.” Yet it was no fantasy, no rendering of an ideal in ink or oil. Rather it stood before him “in great incomprehensible reality,” astounding in its veracity. Contemplating the gigantic whirlpool rapids, he reflected in his diary: “so wild and majestic had I imagined the American landscape, so was the nature in which I imagined the Indians, Cooper’s characters, so was the background I pictured for [Washington] Irving’s histories.” In primeval landscapes, he thought, one might find, indeed one should find, primeval people, original inhabitants: Indians.

Cronau’s melancholy

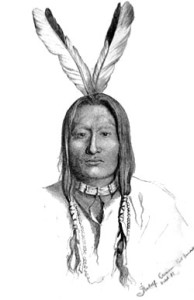

His first encounter with American Indians, however, took place much farther west, and there was little sublime about it. It happened almost inadvertently near Fort Snelling, Minnesota, during a Sunday outing from St. Paul on May 22, 1881. It began with excitement: He recorded in his diaries the initial thrill of seeing “the tops of brown tents” stretching up above the green forest as they approached the settlement. “On the edge of a small lake,” he wrote, “the white tents, now browned from smoke, were a picturesque sight.” Looking for details, he combined his observations with acquired information, explaining that these “wigwams” were cleverly constructed to control the flow of smoke through the opening in the top, and they are quickly accessible through the door at the bottom; in other times and places, he noted, they might also be covered with animal skins or the bark from trees. He included further ethnographic information about these structures in his notes, and then he recorded similar information about their inhabitants: the Sioux (fig. 3).

Around St. Paul, he noted, people generally characterized the Sioux with references to the 1862 Dakota conflict and the massacres of German-American settlers near New Ulm. The “redskins” he encountered near Fort Snelling, however, “had been friendly minded for years” and had long since “opened the door and the gate to civilization’s influence.” That was immediately apparent, he wrote, in their clothing: most of the men “wore hats and bright shirts, pants and vests,” while the women were clad in “jackets and skirts made of cotton and wool.” Moccasins were the footwear of choice. Aside from their shoes, however, “there was no longer any sign of their national costume.”

That romantic element, and the link it documented to the natural sublime, the link he expected to find among Cooper’s characters, was gone. These people were not like Cooper’s Indians, just as Minnesota was no longer primeval forest or sublime landscape. The forces that shaped and fed the hypermodern cities of the East, he recognized, had flooded west across Minnesota, fundamentally changing the land and its inhabitants—which left him disconcerted.

Indeed, to Cronau, the Dakota he met near Fort Snelling seemed more akin to the “wilting leaves” in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem Hiawatha than to the bold characters in Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. Thus, he quotes Longfellow extensively for Die Gartenlaube’s readers, using Hiawatha as a means of introducing his subjects, and as a way of explaining their fate. While standing by a waterfall near Fort Snelling, he explained, his imagination escaped into a time now past, into “Longfellow’s wonderful poem,” and into his portrait of “Minnehaha, the laughing water.” “Wistfully,” he told his readers, he reflected on the fact that the people about whom the poem was written were “scattered or all but exterminated, while a foreign language, the language of their destroyer, sings of their Gods and heroes.” “That,” he lamented, “is a cruel irony of history.” For although “The Song of Hiawtha is a pearl in the crown of American poetry,” the conditions he observed in Minnesota begged him to ask: “Who spared the heroes about whom the song sings in the horrible war of extermination?” Who spared “the poor Indian?”

Cronau’s epiphany

Cronau’s melancholy, however, gave way to anger as he found what he sought in Dakota Territory. His goal in traveling there, as he later wrote in his autobiography, was to “realize a long nourished and favorite wish to become acquainted with the original inhabitants of the New World, so gloriously portrayed in Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales.” And he did. At Fort Yates and the Standing Rock Reservation, at the Pipestone Quarry and the Yankton Agency, and at Fort Randall, Cronau began to channel critical elements in the German love affair with American Indians: He began to take a strong position against the encroachment of white settlers on American Indian lands, to denounce the U.S. government’s handling of Indian affairs, and to condemn widespread arguments about American Indians’ inability to change with the times. He came to regard those arguments as nothing more than a rationalization for expropriating their lands and exterminating them, and his admiration for those who had managed to resist it grew precipitously as he recognized an affinity between his ancestors and the people he came to know.

Here, too, he relied greatly on Germans. Joseph A. Stephan, who was born in Gissigheim in the south German state of Baden, was the Indian Agent at the Standing Rock reservation when Cronau arrived. He welcomed his countryman to Fort Yates, introducing him to the leading chiefs and spending considerable time educating and advising him about Lakota culture and government policies. Fort Yates’s storekeeper was a German as well. So too was the quartermaster at Fort Randall, and his assistant, Fritz Schenk, was from Bern, Switzerland. Schenk guided Cronau through his initial meetings with Sitting Bull and helped him arrange an exhibition of Cronau’s artwork for everyone at the fort, including the Lakota. He also remained a key source of information about life at Fort Randall until Sitting Bull left for Standing Rock in the spring of 1883.

Moreover, throughout his time in Dakota Territory, and afterwards while writing his essays and lectures in Milwaukee, Cronau drew on reports about Indian affairs in many German-language newspapers. They too shaped his opinions and helped him channel a distinctly German discourse.

Most importantly, however, he gleaned information from his observations and from his conversations with the kinds of men he came to find: men of exceptional characteristics; natural men who had done great deeds; men who had not yet been corrupted by the myriad forces of civilization, and who need not be. These were men who could choose to accommodate themselves to those forces, but who were only then, in the fall of 1881, at the moment of choosing.

Cronau believed these men were an integral part of the landscape they inhabited. They were part of the natural sublime, and they harbored an essential masculinity. He saw it evidenced in their raw physicality, and he began rhapsodizing about their magnificent bodies early in his trip. During his first excursion from Fort Yates to the “Hostile Camp,” located just forty-five minutes away, he met with a series of chiefs who presented him with gifts, including an eagle feather from Pretty Bear, which he accepted as a token of great significance. Initially, his notes focused on recording these introductions and detailing the character of the camp. He described the weathered tents, some with painted exteriors, many decorated with scalp locks, bison skulls, and antlers, all showing evidence of the hardships that had brought their owners to the reservation.

His notes, however, moved quickly to the excitement of a dance that seemed to begin almost spontaneously, and which overwhelmed him with stark and vivid impressions of perfect bodies in motion. Enamored with the dancers, he sketched out some of the patterns he saw painted on their faces in his notebook, and he described how they carried their weapons and wore their hair, and as the numbers of participants grew and they mixed into the light from the fires, he became enraptured, proclaiming them “indefatigable,” and writing: “here, as I saw the dancers naked, I had the opportunity to marvel at the veritable athletic and superbly-built bodies of the Indians.” “A large number,” he added, “are six feet high.”

Such men easily fulfilled Cronau’s hopes and expectations of American Indians. He regarded One Bull, whom he befriended at Fort Randall, as “the personified ideal of a Cooper’esque Indian, an Unkas, but more manly, mature, complete, and noble in his movements” (fig. 4). Although Sitting Bull was not as beautiful as the twenty-seven-year-old One Bull, Cronau described him as a “vision of pronounced manliness,” and a “far more important personality than Cooper’s Chingagook,” the father of Unkas, and the model of “authentic Indians” for Cronau’s generation of Germans. In part, that “pronounced manliness” was embodied in his stature. He was a man “of average height, . . . with a massive head, broad cheekbones, blunt nose, and narrow mouth.” When Cronau met him, his “shining black hair hung in braids wrapped with fur that were draped across his powerful chest,” and a “single Eagle feather was placed in his long scalp lock.” His entire body projected physical prowess, just as his eyes and his speech revealed his exceptional nature.

Indeed, Sitting Bull and other Sioux leaders such as Crow King, Gall, and Hump impressed Cronau through their demeanor and words as much as their powerful bodies. Cronau arrived at Standing Rock during a moment of transition. Stephan’s tenure as agent was coming to an end; Major James McLaughlin had just arrived from the Devil’s Lake Reservation to replace him, and Cronau was privy to the initial meeting between McLaughlin and his new charges. He recorded McLaughlin’s speech to them, in which the new agent characterized the Lakota as children who must learn to behave so that he, as their father, could care for their wants and needs and help educate them in the ways of white Americans. What Cronau witnessed in their responses, however, was not childlike. It was inspirational.

Cronau documented the testaments of complete, independent, capable, brave, and self-confident men who commanded supreme respect when they spoke to a room. He recorded in his notebook, for example, the striking impression made by Rain in the Face as he denounced the proceedings and the “crooked tongued” men who the “Great Father” sent them, and then he reflected on this man’s participation in the Battle of Little Big Horn and the rumors that he had cut out and eaten the heart of Thomas Custer. Such men were not easily overcome. Even more impressive, however, was Big Soldier, whom Cronau characterized as a “felicitous speaker whose words rained down like a mountain storm” and who stood directly before McLaughlin, looking him in the eye, and explaining that the “Great Father” had sent many people to them with scores of promises, but they always disappointed.

Cronau’s appreciation of American Indians changed as he witnessed these and other men, including Crow King, Fire Heart, Gall, High Bear, Hump, Running Antelope, and Two Bears face the agent and issue their complaints about the ways in which they had been misled, how whites had eliminated the wild animals, how settlers greedily pressed for more land and offered little reciprocation for what they took. He listened as the chiefs stressed that the agents had continually failed to do their jobs, failed to represent them well in Washington, failed to protect them against the encroachments of settlers. And as he listened, Cronau began to develop his own understanding of a side of American history not present in Cooper’s tales. He began to take a critical position on the history of U.S.-American Indian relations, and he gained further respect for these men.

Thus Cronau’s portraits of them, both his words and his images, not only emphasized their ferocity but also came to include their dignity, intelligence, and wisdom. As a journalist, Cronau understood the appeal of sensation, and he clearly enjoyed describing the most furious and indeed terrifying scenes he had witnessed during the dances. More poignant, however, were his descriptions of the chiefs and their people during ration day: “wrapped in colorful wool blankets or shaggy buffalo skins, with a Tomahawk on an arm,” these men, he underscored, stood before the fort’s commander “with the pride of Roman Senators.”

If Cronau’s respect for these men emerged during the meeting with McLaughlin, it was solidified and deepened through his many conversations with exceptional individuals such as Crow King at Standing Rock, Struck by the Ree at the Yankton Agency, and Sitting Bull at Fort Randall. Cronau’s relationship with Sitting Bull has received considerable attention in Germany, in part because Sitting Bull remains a celebrity there, and because Cronau was the German with the closest contact to him. He is well known for having painted Sitting Bull’s portrait, and for giving Sitting Bull a photograph of himself, which the Lakota leader allegedly kept with him until his death (fig. 6).

Cronau met repeatedly with Sitting Bull and spoke with him at length. Sitting Bull told him about his past, the drawings he had made that chronicled his biography, and which had been sent to a museum in the East, the hard times and hunger in Canada, his dissatisfaction with living on rations, and his desire to have a farm, send his children to white schools, and have them learn trades. Sitting Bull also explained why he had gone to war: He had been forced after the 1862 Dakota war in Minnesota to fight back against the troops that streamed into Dakota Territory, abusing his people. He explained that he had fought against many American Indian tribes as well, refusing to attend the famous peace meeting in 1866, and effectively pushing the Crows, for example, off their lands. He also explained why he had led raids on the gold miners who invaded the Black Hills in 1875, and how he had tried to push the whites out of Lakota lands altogether. Sitting Bull became so animated during these stories that Cronau found it difficult to finish his portrait; but he did complete it, and during their discussions he experienced his epiphany about American Indian affairs as well.

There are three places in his notebooks where Cronau compares the fate of American Indian tribes to the fate of German tribes during the age of Rome: directly after watching the meeting with McLaughlin, after recording his discussions with Sitting Bull, and after his trips in Dakota Territory when he returned to his wife in Milwaukee and spent the winter writing lectures and essays for Die Gartenlaube. Such comparisons between the fate of German and American Indian tribes persist to this day in the German discourse on American Indians.

In “The Denigrated Race,” a lecture he presented to German-American audiences in 1882 and across Germany in 1884-1887, Cronau argued that American Indian tribes, much like German tribes more than a millennium earlier, suffered a devastating invasion from a better-organized and more technically advanced civilization. The consequences for American Indians, however, were more immediate and far greater. The German tribes were armed much like the Romans, and thus they did not suffer from the same disparity of weapons. They were also less alienated than the various tribes of American Indians, and they were not spread out across such vast terrain, and were therefore able to unify much more easily in opposition to Rome. American Indians suffered all those comparative disadvantages and more: they were unable to anticipate the “formidableness or numbers” of their “overpowering opponent,” and the character of the invasion was different as well. The “whites did not come with a large army” to America, as had the Romans to Northern Europe. Rather they came in small groups, “fixed themselves on many different points,” and much like a “slow, lingering, but certain sickness,” much “like a bacteria” against which “there was no cure,” they struck from multiple points of contact. In addition, they brought lethal diseases and alcohol.

Like many other German observers, Cronau denounced U.S. Indian policy. He raged against the constant deception, fraud, and incompetence of government employees charged with maintaining treaties and reservations. He reviled the mean-spiritedness behind the ubiquitous swindles and abuses faced by American Indians who moved onto reservations, and he argued that it was the same mean-spiritedness which had permitted “frontier skirmishes” to develop into a “race war that is still not at an end today [1882].” He blamed the white settlers who lived close to reservations and who coveted American Indian lands for much of the bloodshed during the last decades, and he argued that “ninety-nine out of one-hundred times” violence erupted, it was due to “the same old story:” “broken treaties, unfulfilled promises, and almost incomprehensible injustices.” “Nowhere else,” he argued, “has the collision between white people and another group of people” been so devastating as in North America, and thus he lamented that “the history of the red race in the territory of the Union” must be regarded as “one of the saddest chapters in world history.”

While the anglophone reporters who attended his lectures in Minnesota characterized Cronau’s portraits as typically German, “smacking” of idealized images from Cooper’s tales, and wondered aloud at his audacity for being so critical of government policy while visiting their land, the Germanophone audiences greeted his condemnation with applause and reprinted his arguments in full in their papers. So too did the papers that followed his three-year tour in Germany, where Cronau provided Germans with confirmation of what they already sensed: Germans shared with American Indians a fate, a loss of self, not unlike what many believed they and their ancestors experienced beginning with the influx of Christianity and the hegemonic power of Roman civilization and continuing through the oppressive modern structures that accompanied each successive economic system and state. Those structures had pressed Germans away from nature, away from more direct links to their ancestors, from the land and other species, from a more natural spirituality, an essential masculinity, and into an increasingly material, and often atomized, world. Convinced that they too had experienced a kind of ethnocide in the past, and facing the creation of new, demanding states with almost every generation, these Germans were particularly sensitive to the mixed implications of assimilation facing American Indians during the last two centuries. Thus the affinity at the heart of Cronau’s epiphany reveals the sense of self at the center of the German love affair with American Indians.

Further reading

Cronau’s manuscripts are available in the Solingen City Archive (Stadtarchiv Solingen). Some of his papers can also be found at the German Society of Philadelphia and in the personal possession of Gerald Wunderlich. Cronau’s publications from this period are all in German, but the Gartenlaube essays are easily located in many American libraries. Readers interested in learning more about how Germans and other Europeans viewed Native Americans should consult Colin G. Calloway, Gerd Gemünden, and Susanne Zantop, eds., Germans and Indians: Fantasies, Encounters, Projections (Lincoln, 2002); and Christian F. Feest, ed., Indians & Europe: An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays (Lincoln, 1999). See also Penny, “Red Power: Liselotte Welskopf-Henrich and Indian Activist Networks in East and West Germany,” Central European History 41:3 (September 2008): 447-476; and Penny, “Elusive Authenticity: The Quest for the Authentic Indian in German Public Culture,”Comparative Studies in Society and History, 48:4 (October 2006): 798-818. Pamela Kort’s edited collection,I Like America: Fictions of the Wild West (New York, 2007), is also a useful introduction. Based on a museum exhibition in Frankfurt, it includes many of Cronau’s drawings as well as other illustrations from Germans during this era. Another fine introduction is Peter Bolz, “Indians and Germans: A relationship riddled with Clichés,” in Native American Art: The Collections of the Ethnological Museum Berlin, edited by Peter Bolz and Hans-Ulrich Sanner, 9:22. (Berlin, 1999). For an introduction to Alexander von Humboldt’s broad vision of natural history, see Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe Vol. 1-2 (Baltimore, 1997). Readers who wish to pursue the deep backstory will find Tacitus’ account of Germany’s ancient past inArgicola/Germania, trans. Harold Mattingly (New York, 2009). Karl May books, only recently published in English, are now readily available. The classics are Winnetou vols. 1-3 and The Treasure of the Silver Lake.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.4 (July, 2011).

H. Glenn Penny is associate professor of Modern European History at the University of Iowa. He is the author of Objects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany (2002) and the editor, together with Matti Bunzl, of Worldly Provincialism: German Anthropology in the Age of Empire (2003). This essay stems from his recently completed book,The German Love Affair with American Indians, which is forthcoming with the University of North Carolina Press.