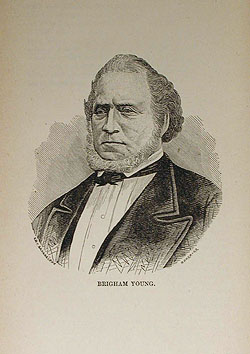

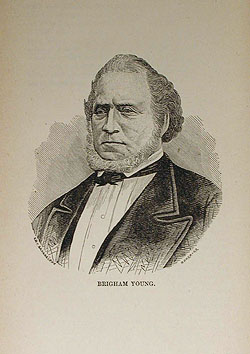

Fig. 2. Brigham Young. From John Doyle Lee, Mormonism Unveiled, ed. William W. Bishop (St. Louis, 1878), 391. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Historian Philip Deloria has argued that a fundamental theme of American culture is a simultaneous effort to displace Native Americans and to inherit, borrow, or perform Native American identity—a practice that he calls “playing Indian.” Pizarro’s elegiac mood—glamorizing the Inca Empire as it went down to defeat—spoke to this ambivalent engagement with Native Americans.

If this ambivalence was a prominent theme in antebellum America, it was even more central to the brand-new Mormon religion. The Book of Mormon, said to have been revealed by an angel in 1827, is in fact a history of ancient Native Americans. Its protagonists are Israelites who came to America by sea in 600 B.C. before splitting into two groups, the good Nephites and the evil Lamanites. Eventually the Lamanites—the ancestors of modern Indians—exterminated their Nephite cousins. The Nephites’ last act was to leave the Book of Mormon to be discovered by Joseph Smith, their latter-day heir.