I.

I have been a Mark Twain fan since I was six years old, even though I did not read a word he wrote before turning ten. What made me a fan was not hearing one of his stories read aloud. Nor was it seeing a play, television show, or film that did it. What made me a fan was my first trip to Disneyland. One of my favorite sections of the theme park immediately became Tom Sawyer’s Island, and I concluded that anyone who could provide the inspiration for it was worth admiring. When I finally got around to reading The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, I was gratified to discover that Twain really was the great writer that I had imagined him to be. I was also relieved that the characters I met on the page behaved like the ones I had conjured up during Disneyland daydreams.

Things have not always worked out quite this way with expectations formed at Anaheim’s famous theme park. Sometimes, the real thing has failed to live up to the promise of the simulation. Other times, encountering the original has left me feeling that Disney did not do it justice. Learning to drive a car fits into the first category, while seeing the Alps fits into the second. Most books first encountered in childhood and revisited years later fit someplace in between. While The Adventures of Tom Sawyer pleasantly confirmed a set of preconceived notions, encountering other books of Twain’s has often worked out quite differently. When I took a course devoted to the author while a college sophomore, I found that some of the texts we read fit in neatly with images I brought with me into the class. Others, however, most definitely did not. By that point, there was a lot that I knew–or, rather, thought I knew–about the author’s life and work. Many different kinds of things had shaped my notions about him–not just those early trips to Disneyland, but also assorted films and television shows, and even some firsthand encounters with Twain’s books. Taking the class, I found that some of my notions were simply wrong. For example, I came in thinking of Twain as someone who only wrote short stories and novels. It was a surprise to find out how large a role travel writings and essays had played in establishing his reputation as a writer. And in my mind Twain was linked only with the South and the Midwest, so it was surprising to discover that he had spent important parts of his life in California and on the East Coast. I guess, most of all, I was surprised to find out how many works by Twain had not been transformed into shows or films. The works I read for that class that I had already been exposed to in some way beforehand, such as A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and The Prince and the Pauper, were certainly enjoyable. But the books that made the deepest impression on me then were several that I had never heard of before.

One of these was The Innocents Abroad, which first appeared in 1869. The book offers a humorous account of an 1867 trip to Europe and the Middle East that Twain took as part of an early group tour. There was something refreshing about reading a book like this, which I came to completely unburdened by expectations. There was no need to ponder, as I read, whether The Wonderful World of Disney had handled the material well. Nor did I find myself thinking about the odd choice a studio had made when casting the lead for a cinematic rendition, as happened when I read Connecticut Yankee with images of Bing Crosby in my head.

Instead, reading Innocents Abroad, which was adapted from letters to newspapers that Twain wrote while taking his tour, I could focus on appreciating the writing simply for its own sake. Well, not quite. The professor teaching the class, though he did a great job at bringing Twain and his times alive, was a bit obsessed with Freudian ideas for my taste. This meant that his students were told to remain vigilantly on the lookout for the appearance of certain kinds of symbols and images. And we were encouraged to be mindful always of how Twain’s humor was linked to a dark view of life and a pessimistic vision of human nature. The professor’s injunctions, though, did little to hinder my uncomplicated enjoyment of books like Innocents Abroad and Roughing It, another book previously unknown to me that became a favorite. In fact, when I started to reread the former, fittingly enough during a recent trip to France (one of the countries described in its pages), I could not remember a single passage that had revealed a Freudian outlook. When I returned to the book some twenty-two years after first encountering it, the only specific passages from it I remembered were silly ones that had made me laugh.

If one section of Innocents stuck most in my memory, it was the part of chapter 27 that finds Twain describing, to delirious effect, how he and some mischievous co-conspirators flummoxed one of their innumerable guides. Sick of having various guides in Italy tell them endless stories about Christopher Columbus, assuming that the great “Christo Columbo” was the one Italian about whom all Americans wanted to know everything, Twain and his partners in mischief took to pretending that they had never heard of the explorer. When the guide showed them a document written by Columbus, they merely commented on the poor quality of the penmanship. (“Why, I have seen boys in America only fourteen years old who could write better than that,” one of Twain’s companions says.) They then asked naively whether this Columbo fellow was dead, a query that greatly irritated the poor guide. So, too, did their irrelevant follow-up questions, such as whether Columbus had died from measles and whether his parents were still alive.

II.

It may seem odd that I began this essay on rereading Innocents Abroad with a series of paragraphs that refer to such quintessentially twentieth-century phenomena as Disneyland, television shows, and films. After all, Twain’s book, in which he often subjects the American travelers in whose company he journeyed to the same sort of humorous scrutiny that he turns on the sites and people of foreign lands, is very much a product of the period in which it was written. That was an era that predated by close to a century the founding of Anaheim’s famous theme park and television’s rise to prominence. The origins of the cinema lie in the very late 1800s, closer to the period of Twain’s first crossing of the Atlantic. Even where film is concerned, however, we are dealing with a medium that did not become a powerful shaper of popular images until Innocents Abroad had been around for about half a century.

This said, it is worth noting that a recurring theme in Twain’s book is precisely the one that my opening paragraphs on Disneyland, television, and film addressed: the experience of encountering for the first time things about which one has already formed images and already has expectations. In Innocents Abroad, Twain repeatedly explores his responses to encountering directly for the first time something to which he has already been exposed in an indirect manner. Sometimes, he describes his initial encounter with the real thing as a source of disappointment, of the sort I felt when I discovered how complicated and worrisome driving was going to be until I got the knack of it. Consider, for example, the section of chapter 34 titled, tellingly, “The Turkish Bath Fraud.” According to Twain, his first Turkish bath was a terrible, indeed traumatic experience, so shockingly devoid was it of the elegance that literary accounts had led him to anticipate.

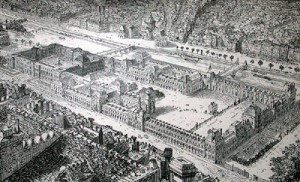

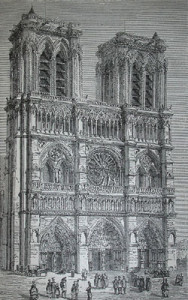

In other cases, though, Twain shows us how previous exposure via representations can give a new experience a pleasing sense of familiarity mixed with novelty, akin to what I felt when reading Tom Sawyer, after being primed for it by Disneyland. He describes “speeding through the streets of Paris” for the first time, all the while “delightfully recognizing certain names and places with which books had long ago made us familiar.” Seeing pictures of the Louvre in advance prepared him for the look of the “genuine vast palace” itself; it was “like meeting an old friend when we read ‘Rue de Rivoli’ on the street corner”; and he instantly recognized the “brown old Gothic heap” that was Notre Dame, since it was so much “like the pictures” of it he had seen.

In still other cases, he claims, encountering a site about which he thought he knew what to expect in advance could turn out to be nothing short of a revelation. Take, for example, his section on “The Majestic Sphinx,” in which he describes seeing for the first time in person an Egyptian icon that was doubtless as familiar to him via representations of various sorts as the Matterhorn was to me during my Southern California childhood. “After years of waiting, it was before me at last,” he writes, and then begins describing its wondrous qualities in a way that makes it clear that he was unprepared for just how impressive he would find it. So taken with it was he that his description of the Sphinx stands out as an unusual part of the book, since in extolling its glories, Twain drops his usual satirical tone and just enthuses.

But sometimes, Twain suggests, only true novelty–a first encounter, devoid of expectations–will do. “One charm of travel” dies for him in Rome, where he finds there is nothing “to feel, to learn, to hear” that others have not already felt, learned, and heard. While Twain makes it clear that he does not yearn for actual discovery–being the first to go somewhere–he hungers occasionally for the next best thing: to see sites that have not inspired artistic creations or made it into guidebooks.

III.

Twain’s interest in exploring and teasing humor out of the interplay between expectations and encounters resonates powerfully with contemporary concerns, as does his feeling that having clearly formed images of places in advance can sometimes add to but sometimes detract from the experience of travel. Much has been made of late of how important simulations have become in our twenty-first-century lives, and how new media have begun to drown us in representations. And much has also been made of the way that, in the current age, the tourist industry has to play to our desire for both familiarity and the exotic. We want to see firsthand places that we feel we know already, thanks to their appearance in movies, specials on the travel channel, National Geographic feature stories, and so on. And yet, as the popularity of “rough guides” show, we also hunger to get off the beaten track at least a bit and come as close to “discovering” things as we can in an era of information overload.

There are many novelties about the current situation, of course, in terms of the specific media that shape in advance our images of distant places and the way we prepare for trips to far-off locales. Before leaving the United States, Americans can now journey into cyberspace not only to find places to stay but also to see images of their future accommodations. We did just this before the four of us set off to France last June. Prior to arriving in Paris, my wife showed our two children and me a Website that contained a photo of the Parisian apartment she had rented for us. Moreover, sometimes when Americans go abroad, they take with them images of a foreign country formed by more than just things they have read in books and seen on television screens, movie screens, and computer screens. Before our eleven-year-old daughter and fourteen-year-old son ever crossed the Atlantic, for example, they had visited the faux version of France that can be found at Epcot Center. (Just go past Norway and China; if you reach Morocco, then you have gone too far.) It remains an open question, though, whether these sorts of novelties mean that a chasm separates travelers of 1867 and 2004 when it comes to the interplay between images and experience. And reading up on the role of simulations in Twain’s day has convinced me that the divide between then and now is a much subtler one than it appears at first to be.

The work that has done most to push my thinking in this direction is historian Vanessa Schwartz’s fascinating 1998 University of California Press book, Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris. One of Schwartz’s main themes is that the nineteenth century, like the twentieth, witnessed the rise of many forms of mass media, from serialized novels to panoramas. Another is that, as a result, the mid-to-late 1800s were, like the present, a time when the lines between simulations and “reality” were continually being drawn, erased, and blurred in alternately confusing, disturbing, and exhilarating ways.

There is much in Twain’s account that illuminates the role that the “new media” and newly important genres of the 1800s could have on a traveler. For example, though he could not see any cinematic representation of the Castle d’If before reaching that famous prison, he makes it clear that reading popular novels by Dumas that included scenes set within that edifice colored completely his first direct encounter with it. In addition, though he obviously could not go on the Web to get a preview of his living-quarters abroad, he did read brochures and guidebooks that gave him clues about what to expect. And, as with the Web, the information Twain gleaned from them turned out to be not so much inaccurate as incomplete. The digital photo of our Parisian apartment did not prepare us for the heady aroma that would enter it whenever we opened a window, due to the apartment’s proximity to a string of Egyptian, Greek, and Indian restaurants. Similarly, Twain was surprised that the guidebooks that sang the praises of the soaps of Marseilles did not tell him how hard it would be to find any bars of this substance with which to wash in that city’s hotels.

Switching from sites and accommodations to famous works of art, it is easy to imagine Twain feeling a kinship with the many contemporary travelers who wait in line in Paris to see the great Mona Lisa up close–then go away vaguely unsatisfied. Yes, these people say, it does look just like it does on the greeting cards and t-shirts. But it is hard to appreciate the famous smile when you come close to it, since the glass case encumbers your view. This postmodern disappointment echoes Twain’s reaction to another Da Vinci work, The Last Supper, which he calls “the most celebrated painting in the world.” When he saw The Last Supper, Twain writes, he “recognized it in a moment,” as it had served for centuries as the model for many “engravings” and “copies.” “And, as usual,” he continues, making a comment that he made as well about other renowned works, “I could not help noticing how superior the copies were to the original, that is, to my inexperienced eye.” They were brighter and clearer, for example, the details easier to make out.

Still, one might object, there remain some dramatic contrasts between our day and Twain’s. Yes, there may be contemporary counterparts to the know-it-alls of the 1860s that Twain lampoons, who would spout out, as though they were spontaneously formed opinions, impressive sounding comments on famous sites that turned out to be taken verbatim from a guidebook. The only difference is that now, the plagiarists often go to the Web rather than printed matter for inspiration. But surely, one might argue, there was nothing around in Twain’s time comparable to Epcot. To experience foreign travel then, you had to actually go abroad, did you not? Is it not only recently that going to an entertainment site can give one a literal and metaphoric taste of distant lands, a taste that can prepare you for an actual journey–or take the place of this kind of expensive and inconvenient undertaking? Can we not safely put Disney World in a special category, reserved for contemporary simulations? The answer to all of these questions, I think, is actually no.

Consider, for example, the panoramas and dioramas of the 1800s. In 1824, one travel writer called panoramas “among the happiest contrivances for saving time and expense,” since for a “shilling and a quarter of an hour” they allowed one to make a journey that once cost “a couple of hundred pounds.” Sometimes, panoramas displayed events, such as battles, but sometimes they just represented locales. The same was true of dioramas. In 1845, for example, crowds flocked to a Parisian diorama devoted to simulating the experience of seeing St. Mark’s in Venice. In short, as Schwartz puts it, panoramas and dioramas were early forms of “‘armchair’ tourism” that might “substitute for travel.” Such spectacles belonged to a milieu that included many other sorts of popular simulations that made a fetish of “realism,” yet often included fanciful elements. Wax museums, for example, and the Paris Morgue, a site open to public viewing where bodies awaiting identification were placed on display, sometimes posed in dramatic ways or surrounded by props.

We do not know from Twain’s account whether he saw any panoramas or dioramas or wax tableaus, either before or after heading across the Atlantic, that prepared him in advance for any particular sites. We do know that, while in Paris, he joined the crowds outside the windows of the morgue. And, more significantly, he went to the 1867 International Exposition, also in Paris. The great international expositions and exhibitions of the nineteenth century–two of the most famous of which were in London in 1851 and in Chicago in 1893–were precursors of the World’s Fairs of the twentieth. And these in turn would serve as models for the Disney theme parks.

Twain spent only two hours at the exposition–in part because he “saw at a glance that one would have to spend weeks–yea, even months–in that monstrous establishment, to get an intelligible idea of it.” But he viewed his short time at the gala as a kind of miniaturized version of a world tour. The formal exhibits added up, he wrote, to a “wonderful show,” allowing visitors to see objects from various regions. And yet, he writes, “the moving masses of people of all nations” made “a still more wonderful show,” and he closely examined the faces and modes of dress of those who passed by. It is perhaps no accident that one party he was especially fascinated by was made up of people who had come from the Middle East, the part of the world toward which he was headed.

IV.

Since rereading Innocents Abroad, I have been asking myself three different sets of “what if” questions about Twain’s voyages across the globe and on the page. One set has to do with sites associated with him that are now part of tourist itineraries. What would he make of his birthplace in Hannibal, Missouri, becoming a heritage site? Would he be flattered, annoyed, or simply amused by Tom Sawyer’s Island? And what would he say about the fact that the Magic Kingdom that now stands near Paris does not include this attraction? (Full disclosure: I have not made it to the European park yet, so my information comes from a bit of armchair travel–done twenty-first-century style, of course, via the Web.)

The second sorts of “what if” questions I have been asking myself have to do with what Twain would have thought of Shanghai, the subject of my current research, had he visited there in the late 1800s. He had plans to go China after completing his 1867 trip across the Atlantic, but despite an enduring interest in the country, he never made it. Twain wrote some interesting things about American policies toward China and about treaties that affected the city I study. And a character in one of his works of fiction sets off for America from there. But I can only imagine–and this is frustrating for a Twain-loving Shanghai specialist–what he would have actually thought about the sights, sounds, and smells of the city in the late 1800s. Would he have thought that parts of the old walled city of Shanghai were strangely familiar when he arrived, due to his prior viewings of Chinese artifacts at international exhibitions or visits to one of America’s Chinatowns? And if he had made it to Shanghai, would he have thought that the illustrations he had seen ahead of time of the new Western-style buildings of the famous waterfront “Bund” that ran through its newer foreign-run districts had done them justice? There is, alas, no way to know for sure.

The final set of hypothetical questions I have been asking myself are what Twain’s reaction would have been to certain experiences we had during our recent trip to France. I have decided that he would have liked our Parisian apartment, as the view from its window was a bit like a peephole into an international exposition. Looking out, we could see “people of all nations” pass by, as well as restaurants that not only served food from different countries, but also had hosts or hostesses wearing the traditional clothing of and contained objects associated with those countries. One restaurant had a white statue of a Greek hero, another a sign saying, “Visit Egypt,” and a picture of the Pyramids. Our view was, in a sense, a window onto a miniature Epcot-on-the-Seine.

Another thing about our recent trip that would have impressed Twain is the speed with which we made the journey from Paris to Marseilles. In Innocents Abroad, Twain describes his preference for traveling by stagecoach rather than train, finding railway trips “tedious” and lacking in drama. Still, he was such an admirer of technological breakthroughs that he would have marveled that the TGV could whisk us from Paris to Marseilles in just a few hours. I am less sure what he would have thought of the precise fashion in which we made that journey. Though we had reserved seats, a strike leading to the cancellation of two-thirds of the southbound trains forced us into a small space usually reserved for luggage. Would he have found this a charming throwback to rough and ready travel by stagecoach? Interpreted it as a sign of the importance human factors will always have, no matter what technology accomplishes? Or simply lamented that we were deprived of seeing the landscape between Paris and Marseilles that he had found “bewitching”? There is no way to know.

Similarly hard to decide is what he would have thought about Nice, our final stop, which was not on his 1867 itinerary. Since Twain wrote a few revisionist accounts of Old Testament stories, it would be interesting to bring him back to life and ask his opinion of the representations of these tales in the Chagall Museum. And I would like to hear his comments, after a few days in Nice, on the ways that the clothes people wear at the seaside and the kinds of boats that ply the Mediterranean have changed since the 1860s. Most of all, though, if I could ask the author of Innocents Abroad about just one thing that we saw in Nice, it would be a restaurant-cum-nightclub called “Le Mississippi,” which stands near the city’s famed Hotel Negresco. From peeking into its window, my sense was that the main goal of the décor of Le Mississippi is to simulate for patrons the feeling of being on board a nineteenth-century American riverboat of the sort frequented and then made globally famous by Mark Twain. I would love to know the great man’s reaction to this place, the French Riviera’s glitzy answer to Tom Sawyer’s Island.

Le Mississippi’s existence intrigues me for another reason: it reminds us that cities throughout the world are now filled–much more so than in Twain’s day–with sites that provide residents of other countries with simulated encounters with imagined Americas. It is worth keeping in mind that such simulacra–including, for example, the Hard Rock Cafés found everywhere from Beijing to Buenos Aires–can be powerful shapers of images. And it is worth considering, as I did in Nice, that such sites may seem just as exotic as additions to the local landscape as Epcot’s faux Eiffel Tower is to that of Orlando.

Further Reading:

On Twain as a travel writer, see Jeffrey Alan Melton, Mark Twain, Travel Books, and Tourism: The Tide of a Great Popular Movement (Tuscaloosa and London, 2002). And for a very good general reference work on the author, see A Historical Guide to Mark Twain, edited by Shelley Fisher Fishkin (Oxford, 2002). The Innocents Abroad (1869) is readily available in several editions. The 2002 Penguin Classics edition–which comes with an introduction by Tom Quirk that does an excellent job of describing and placing into context the evolution of Twain’s account of his travels–was the one I took with me to France. There is also a 2003 Modern Library edition that I discovered after my return but before completing this essay, which contains a poignant introduction by Jane Jacobs that is particularly insightful on the interplay between mockery and empathy in Twain. In addition, there is a digital version of the book–and related materials, such as sample advertisements for it that were used to sell it when it first appeared–available here. On the general subject of travel and tourism, a good collection of recent scholarly writings is Shelley Baranowski and Ellen Furlough, eds., Being Elsewhere: Tourism, Consumer Culture, and Identity in Modern Europe and North America (Ann Arbor, 2001). On simulations in the nineteenth century, see Vanessa Schwartz, Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-De-Siècle Paris (Berkeley, 1998), and also Richard Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge, Mass., 1978). For further readings on Paris around the time of Twain’s visit, the citations in Schwartz, Spectacular Realities, will take you to a variety of relevant works by Walter Benjamin and many others. For an idiosyncratic but fascinating account of spending time in this same city as an American toward the end of the twentieth century, see Adam Gopnik, Paris to the Moon (New York, 2000). And for the history of Nice and its changing place on tourist itineraries, start with Orvar Löfgren, On Holiday: A History of Vacationing (Berkeley, 1999), 163-66, and proceed from there to the works he cites in his footnotes.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.3 (April, 2004).

Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, a specialist in cultural history and modern China, is the director of the East Asian Studies Center at Indiana University. His most recent book, as editor, is Twentieth-Century China: New Approaches (New York and London, 2003). He is a regular contributor to the TLS and has had essays appear in various magazines, including the Nation and Newsweek. He is currently working on a book-length study of Shanghai’s past and present as a global city.