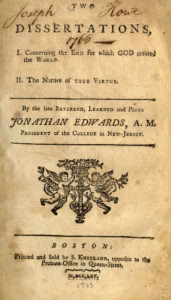

Because Phillis Wheatley’s “On Virtue” is one of the first poems that she wrote, it is often dismissed as a poem of juvenilia. But this poem demands reexamination, as it is where Wheatley first engages with Jonathan Edwards’s theology. Though it is impossible to know whether Wheatley read any of Edwards’s writings, most of his texts—including The Freedom of the Will (1754) and The Nature of True Virtue (1765)—were first published and sold in Boston at Samuel Kneeland’s print shop, which was located a few blocks away from the Wheatleys’ King Street mansion. According to the “Proposals” for her volume of poetry, which was first printed in the Boston Censor on February 29, 1772, Wheatley wrote “On Virtue” in 1766. That Wheatley composed her poem within months after Edwards’s text on the same topic posthumously appeared in print only further supports the possibility that “On Virtue” is Wheatley’s poetic response to Edwards’s conception of virtue.

Placed second in her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), “On Virtue” is a short poem that details the process of evangelical conversion. The poem begins with Wheatley describing Virtue as being out of reach to the human mind: “O Thou bright jewel in my aim I strive / To comprehend thee. Thine own words declare / Wisdom is higher than a fool can reach.” In True Virtue, Edwards similarly argues that virtue is beyond most people’s understanding because it is closely associated with God—that God’s “being above our reach . . . [shouldn’t] hinder that he should be loved according to his dignity . . . we must allow that true virtue does primarily and most essentially consist in a supreme love to God.” Though Wheatley concedes that she will “no more attempt” to mentally “comprehend” Virtue, she does encourage her soul to have a more immediate interaction with it: “But, O my soul, sink not into despair, / Virtue is near thee . . . Fain would the heav’n-born soul with her converse, / Then seek, then court her for her promis’d bliss.” It is only after Wheatley acknowledges her soul’s ability to connect with Virtue that its “sacred retinue descends” from heaven to greet her: “Array’d in glory from the orbs above. / Attend me, Virtue, thro’ my youthful years! . . . guide my steps to endless life and bliss.”

In agreement with Edwards, Wheatley argues that Virtue is a divine and “sacred” quality (it is “array’d in glory from the orbs above”). Yet Wheatley additionally alludes to Edwards when she asks Virtue to “embrace” her soul and “guide [her] steps to endless life and bliss.” For in Freedom of the Will, Edwards also claims that one’s soul is capable of influencing the way one walks: “And God has so made and established the human nature . . . that the soul preferring or choosing such an immediate exertion or alteration of the body, such an alteration instantaneously follows. There is nothing else in the actings of my mind, that I am conscious of while I walk . . .” The reason that Edwards is conscious of nothing while he walks is because his newly converted soul has suspended “the actings of [his] mind.” By saying that his body only moves as a result of his soul’s and not his mind’s “preferring or choosing,” Edwards argues that when one undergoes a conversion experience and gives one’s self up to God, one no longer has complete control over one’s own body. Wheatley’s saying that her soul touched by Virtue can “guide [her] steps” is thus more than just a metaphor for God’s ability to change a converted person’s life: it is an acknowledgment of the immense power that God’s virtuous character can have over a person’s body and soul.

This idea that one’s spiritual status is reflected in the way one walks recurs in black evangelical writing in the early-national period, most especially in Lemuel Haynes’s sermons. Like Edwards and Wheatley before him, Haynes, in his 1776 sermon on John 3:3, argues that a converted man “evidences by his holy walk that he has a regard for the honour of God.” Though she was not a minister, Wheatley was, like Haynes, deeply invested in Edwards’s theology and advanced his theory of conversion. Placing Wheatley’s “On Virtue” in dialogue with the writings of other evangelical ministers, black or white, is one of the many ways that scholars can begin to value Wheatley as a formidable theological thinker in the colonial era.

Further reading:

The most authoritative edition of Wheatley’s writings is Complete Writings, ed. Vincent Carretta (New York, 2001). Haynes’s writings can be found in Black Preacher to White America: The Collected Writings of Lemuel Haynes, 1774-1833, ed. Richard Newman (Brooklyn, 1990). The most authoritative editions of Edwards’s writings are from Yale University Press; Freedom of the Will is found in the collection’s first volume and True Virtue is located in the eighth volume. Cedrick May is one of the only other scholars to discuss the affinity between Edwards’s and Wheatley’s theology; see his Evangelism and Resistance in the Black Atlantic, 1760-1835 (Athens, 2008). For more information on Samuel Kneeland, see Jonathan Yeager, “Samuel Kneeland of Boston: Colonial Bookseller, Printer, and Publisher of Religion,” Printing History 11 (2012): 35-61. Eighteenth-century maps of Boston show that King Street (location of the Wheatley mansion) becomes Queen Street (where Kneeland’s shop was located) upon crossing with Cornhill Street. The “Proposals for Printing by Subscription, A Collection of Poems . . . by Phillis, a Negro Girl” was reprinted in the Boston Censor on three occasions in 1772; it is reproduced in Carretta’s edition of Wheatley’s Complete Writings.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.3 (Spring, 2017).

Michael Monescalchi is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Rutgers University. He is writing a dissertation on how the Christian ethical theory of disinterested benevolence affected reform philosophies in the early-national era.