Maritime Minstrelsy Along the Transoceanic Frontier

The significant global footprint America’s nineteenth-century maritime community possessed certainly did not escape observers at the time. One editorialist at the Sailor’s Magazine, a periodical devoted to nautical affairs, remarked in 1832 that the nation’s seamen “are visiting every port in the world, they are mingling among the nations, they have intercourse with every kindred and people and tongue, and are situated to exert a mighty influence.” The New Bedford Port Society asserted as well that mariners were “by no means unimportant as it regards our national character.” Unquestionably “the most numerous and frequently the most important ambassadors of nations,” shipboard laborers “supply the principal elements from which the conclusions are formed in distant regions, of the people who send them forth.”

Sailors, in other words, were chiefly responsible for introducing the United States to the world, and would shape public opinion overseas regarding Americans. “We judge of other nations by the individuals we see,” the Sailor’s Magazine further reasoned, just as Americans “estimate the character of our Brethren of other States in the Union by the specimens we have seen of their citizens.”

If peoples overseas would judge America and Americans by its largest class of representatives, it seems significant that those men often appeared in blackface. Whatever conclusions individuals abroad reached about the United States derived in part from maritime minstrel recitals. Many mariners, in fact, appeared anxious to perform American racial caricatures for people they encountered overseas.

Blackface minstrel shows remained among the most wildly popular modes of entertainment available to antebellum citizens, particularly those who dwelled within the northeast’s commercial corridors. Tracing its origins as a theatrical form to the earliest decades of the nineteenth century, minstrelsy had, by the 1830s, been transformed into mass entertainment by the likes of men such as Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice. A white traveling actor who worked developing towns along the nation’s western rivers, Rice reportedly observed and then replicated on stage the song and dance of a crippled enslaved stable hand from Louisville. Using burnt cork to black his face, appearing in the garb of a “plantation darkey,” and using dialect associated with peoples of African origin, Rice initially inserted his act as a short accompaniment to longer dramatic productions. That routine quickly became the minstrel mega-hit “Jump Jim Crow,” named after the song’s chorus where Rice, in affected speech, claimed to “Wheel about, an’ turn about, an’ do jis so/Eb’ry time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow.” Debuted in 1828, Rice’s number grew in scope as the actor responded to enthusiastic audiences by continuously adding new verses and steps. By 1830, the flutter of his feet—and a growing army of imitators’—ignited a popular cultural wildfire. Regularly packing houses in New York, Rice became a transatlantic sensation by 1836 after he completed tours of England and France. It was with minimal exaggeration that an 1855 retrospective in the New York Tribune could claim that “[n]ever was there such an excitement in the musical or dramatic world; nothing was talked of, nothing written of, and nothing dreamed of, but ‘Jim Crow.’ ” Indeed, it appeared as though “the entire population had been bitten by the tarantula; in the parlor, in the kitchen, in the shop and in the street, Jim Crow monopolized public attention.”

Yet stories of blackface minstrelsy’s plantation origins like the one Rice told are probably apocryphal. He and many of the era’s best-known white caricaturists, after all, grew up in Manhattan’s racially integrated dockside districts. There they would have witnessed all manner of pseudo-theatrical spectacles, from masked mummers to free blacks dancing for eels, oysters, and loose change. Historians now agree that this vibrant urban culture of song, dance, and holiday exhibition among the city’s poorest white and black residents is the more likely source for minstrel material. What would later sicken Frederick Douglass as “the filthy scum of white society [stealing] from us a complexion denied to them by nature” traced its origins to cross-racial contacts along the New York waterfront. This harborside habitation provides a window into one of blackface’s more curious and understudied dimensions: international, nautical performances. Seafarers made it so. Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and their immediate environs—that is, the country’s largest seaports, its gateways into the wider world—hosted thousands of minstrel shows annually, their seats packed with sailors. The famed theatres of E.P. Christy, Daniel Emmett, and Henry Wood opened their doors to largely white, male audiences, many of whom, upon witnessing the display, thereafter hopped aboard vessels bound outward across the globe. Ships’ decks served as readymade venues for the execution of minstrel shows abroad, and seamen often seized the opportunity to perform before mixed crowds of fellow mariners, local officials, and indigenous peoples. The enthusiasm some sailors showed for reproducing American racial spectacle overseas suggests not only their own warm embrace of the era’s popular theatre, but also their aspiration to familiarize foreign societies with the nation’s cultural landscape. In the foreground of that landscape lay the questions of class, race, and slavery which blackface performance worked to articulate.

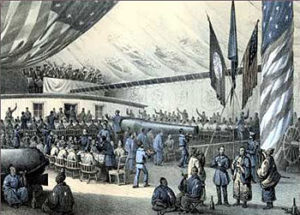

The best documented of these episodes occurred during Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s famed 1852 mission to “open” Japan. President Millard Fillmore, with the staunch support of Secretary of State Daniel Webster, had authorized the use of four vessels to establish formal diplomatic and commercial relations between the United States and Japan. America’s presence in the Pacific had grown steadily over the nineteenth century, and with the U.S.-Mexico War securing for the nation permanent frontage along the globe’s greatest ocean, hungry eyes now gazed upon the lucrative prize that was East Asian trade. Japan presented the prospect not only of new customers for American goods, but, more significantly, the strategic location for coal depots required by transoceanic steamships. The expedition itself would be an instrument meant to forge another link in what Webster and the mercantile interests he represented began to call the “Great Chain” of saltwater commerce that would connect the United States to the wider world (fig. 1).

Using supposed Japanese mistreatment of shipwrecked American sailors as a pretext for armed intervention, American officials charged a reluctant Perry (who had expected to spend the remainder of his career in the comfort of a Mediterranean sinecure) with the difficult task of convincing that relatively hermetic realm to associate with what its leaders considered to be a barbarous outside world. Perry’s squadron, an assemblage of the United States Navy’s most modern steam warships, bristled with cannon meant to impress upon the Japanese the violent alternative that continued isolation would entail. Other scholars have made much of the “gifts” to the ruling daimyo included as part of the expedition. In the printing presses, Colt weaponry, telegraphic demonstrations, and miniature steam locomotive, they find a “technological imperative” behind America’s civilizing mission. Without denying the centrality of industrial expertise to American imperial agendas, though, we need to ask why a minstrel show organized by the squadron’s white sailors became central to narrative and pictorial accounts of the expedition (fig. 2).

For the seamen who blacked up, “demonstrating America” was not reduced to displaying feats of engineering. Rather, exposing the Japanese to American civilization meant educating them in the proper racial order. If the “Land of the Rising Sun” was to become civilized, its inhabitants would require instruction in the sort of prejudice befitting civilized peoples. Just as blackface is thought to have tutored recently arrived immigrant populations in the United States in domestic racial hierarchies, so, it was hoped, would it function abroad in broadcasting the implicit inferiority of dark-skinned peoples everywhere. Certainly the Japanese themselves were the targets of racially based animosity across the nineteenth century. But if Asiatic peoples were not the equal of the omnipotent Anglo-Saxon, they might nevertheless revel in their superiority over still lowlier races (fig. 3).

We do know what the Japanese saw, if not how they saw it. Certain portions of the show found their way into the pages of expedition journals. Those reports reveal a flurry of affected speech, “dancing that surpassed all,” and slapstick comedy routines, so that by the show’s conclusion, one observer thought that the Japanese “commissioners would have died with their laughter.” Perry’s official interpreter, S. Wells Williams, asserted that “the exhibition was a source of great merriment to them and every one present, for the acting was excellent.” Other sailors also believed the performance a great hit among the Japanese, though one man took enough time to consider the question of reception: “The guests seemed quite pleased—they laughed a lot—but why? Perhaps even they did not know.” The Commodore himself did not fail to record the event, albeit tersely. The treaty commissioners “were entertained on deck with the performances of the very excellent corps of Ethiopians belonging to the [ship] Powhatan,” wrote Perry, who praised the “hilarity which this most amusing exhibition excited.” He invoked the famed American minstrel proprietor E.P. Christy to depict the Japanese laughing “as merrily as ever the spectators at Christy’s have done,” so much so, in fact, that one man draped his arm over Perry’s shoulder for support as he doubled over, and, as the commander complained, “crushed my new epaulettes.” Francis Hawks, the expedition’s official chronicler, concurred with the Commodore: “[the] exhibition of Negro minstrelsy … would have gained them unbounded applause from a New York audience even at Christy’s.” And importantly, as Hawks made entirely clear, the minstrel show was the sailors’ initiative, or, in Perry’s words, “got up by the sailors” (fig. 4).

Portraying sailors as particularly invested in the minstrel portion of the expedition’s agenda encourages us to compare it to those more “official” components of Perry’s mission. The Commodore paid particular attention to the appearance of ships, weaponry, uniforms, and other ceremonial vestiges. His diplomacy consisted of gifts, niceties, and calibrated decorum, all designed to display the power and prestige of the American nation. Yet George Preble, one of the expedition’s lieutenants, remembered Perry confiding among the men that their contribution to the mission remained crucial: “The Commodore … said the success of his treaty depended upon the success of the entertainment.” Hence, declared Preble, “we did our best.” The crew, in other words, were conceded minstrelsy as their own form of diplomatic ritual. In denigrating African Americans, they communicated to Japanese onlookers, in some essential way, the United States. And if broadcasting race was a primary motive of the minstrels overseas, there is some evidence to suggest its success: later accounts of prejudice in the Meiji empire note that Japanese diarists, in the words of one scholar, consistently referred to blacks as “pitifully stupid, grotesque, dirty, unmannered, physically repulsive subhumans … with faces resembling those of monkeys.” In that sense, supposedly “American” minstrelsy could be seen as a tool to sustain not only white national identity in the United States, but also national or cultural identities in Japan and elsewhere predicated upon black inferiority (fig. 5).

It was not simply the “Opening of Japan” that was attended by minstrel diplomacy. Rather, sailors showed enthusiasm for the ritual wherever they traveled. An unidentified midshipman aboard the USS United States wrote in 1844 at Mazatlan, along Mexico’s Pacific coast, that numbers of the ship’s sailors organized themselves for a minstrel show aimed at “jollification.” The “whole of them amused themselves with patting juba and dancing breakdowns … and singing negro songs.” Local officials, native peoples, and even the French Consul all attended the event, which seemed to please every spectator. Richard Henry Dana, while ashore at Santa Barbara, California, remarked that one of his shipmates “exhibited himself in a sort of West India shuffle, much to the amusement of the bystanders.” Other portions of the text made clear that “West India” was a synonym Dana used to connote “blackness,” as in the objection to hauling hides atop his head because it “looked too much like West India negroes.” Meanwhile, in 1841 Merida, Mexico, diplomat John Lloyd Stephens was welcomed ashore by a local brass band playing the minstrel song “Jim Crow” under the erroneous impression that it was the U.S. national anthem: “The band, perhaps in compliment to us, and to remind us of home, struck up the beautiful national melody of ‘Jim Crow.'” An honest mistake, Stephens thought, given the frequency with which American naval bands were appropriated for minstrelsy overseas. In Hakodate, a relatively remote whaling port in northern Japan, a group of men aboard the bark Covington in 1858 came ashore to witness the traditional theatrical practice known as kabuki. Quickly bored with the entertainment (the actors “were not what would be called ‘stars’ at home,” one sailor quipped), the mariners provided their own, as described by seaman Albert Peck:

There were about fifty sailors collected here and after witnessing the performance for a while the stage was taken possession of by them and there being fiddlers banjo players &c. amongst them a negro concert was improvised and the stage resounded to the steps of the Juba dance with varieties which gave immense satisfaction to all in the theatre.

All, that is, save the Japanese actors, who, Peck noted, “appeared highly indignant at being interrupted in their performance and driven from the stage.” The remaining three weeks of the vessel’s time in port saw the theater repurposed for minstrelsy, homage paid to William Henry Lane, also known as Master Juba, famed African-American dancer in New York’s Five Points slum.

And while the routine rendered before Japanese treaty commissioners may have been the most significant blackface display during the Perry expedition, it was by no means an isolated event while the squadron was abroad. “There are always good musicians to be found among the reckless and jolly fellows composing a man-of-war’s crew,” Perry professed, and regular evening entertainment aboard ship ordinarily involved minstrel favorites such as “‘Jim along Josey,’ ‘Lucy Long,’ ‘Old Dan Tucker,’ and a hundred others of the same character.” They “are listened to delightfully by the crowd of men and boys collected around the forehatch, and always ready to join the choruses.” Another observer remarked that “every morning … the cooks and sailors get together forward with a banjo and tambourine, singing all the nigger melodies with a voice and taste that would make the Christy Minstrels applaud.” Minstrelsy, then, was embedded in the ship’s daily routine.

Other diarists noted the frequency with which the Perry squadron’s sailors applied the burnt-cork mask throughout the voyage’s three year duration. Aboard the USS Powhatan at Hong Kong in December of 1853, Thomas Dudley noted that “we are amusing ourselves and friends on shore. Minstrelsey and balls have been given on board two of the [flotilla’s] steamers, and we have done our share … winning merited applause for [our] excellent endeavors.” Several months later and farther north along the Chinese coast, “all Shanghae was invited [aboard ship] and came, first we gave them 2 hours entertainment from the negro minstrels [for whom] there was unbounded applause, all went off first rate, then we had refreshments, and then a grand ball.” Later still, the ship’s “minstrels gave performances which delighted the residents of Canton.” And in a letter home to his sister dated December 20, 1853, Dudley went on in great detail regarding the regularity with which the navy’s sailors turned blackface performers:

We have a minstrel band of 9 performers, that do beat Christy’s all hollow. One of them does up Lucy Long tip top, and they are always well received. Every Monday we have a performance—alternatively the theatre and “nigger band”—on these occasions the ship assumes a gala appearance and great things are done. The Captain has a great supper for admirals, governors, and other big fish. The Wardroom for Lieut and less fry while we of the steerage entertain the still smaller fry, such as midshipmen, passed mids, etc. etc. The suppers are great, as is everything else. The Susquehannah has a theatre every Wednesday, the Winchester on each Fridays and the Mississippi on Tuesdays, so you see we do not lack for that kind of amusement. Society in China there is not and so we are obliged to turn our ships into playhouses, to interest the men, and amuse ourselves.

In claiming that ships were consistently converted “into playhouses” for the exhibition of a well-practiced “nigger band,” Dudley dramatically illustrated the far-reaching influence of American minstrelsy at the time. Diagnosing China as devoid of “society,” he prescribed racial caricature as an elevating panacea. His assurances that all who bore witness were enamored of the display (the troupe “merited applause” in Hong Kong; they “delighted” in Canton) echoed other observers likewise invested in recording Jim Crow’s sensational reception around the world. Here lay a gesture toward cultural imperialism: America’s mass entertainment embraced by “admirers” overseas living in a social vacuum and desperate for the fulfillment promised by an outside power’s theatrical ingenuity. Boasting of blackface’s endless international appeal clearly celebrated the beginnings of U.S. penetration and domination overseas, but it also negated the need to question or challenge the minstrel show’s potentially problematic representations of slavery and black culture. Affirmation abroad, then, ensured the medium’s perpetuation at home, which, in turn, further guaranteed regular exportation of minstrelsy overseas and the deeper entrenchment of racial stereotypes regarding African Americans.

And naval squadrons more generally seem to have been potent vehicles for the diffusion of minstrel performance. Even before venturing to Japan, the federal government had played an active role in securing America’s position in the Pacific. Building upon the piecemeal efforts of individual commercial ventures, Congress in 1836 authorized the largest exploratory expedition ever sent into the region by any nation. An array of objectives motivated the venture, some scientific, others economic and political. Departing in 1838 with a fleet of five warships and nearly one thousand sailors, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes eventually led the United States Exploring Expedition on a four-year circumnavigation of the globe chiefly celebrated for the discovery of the Antarctic continent.

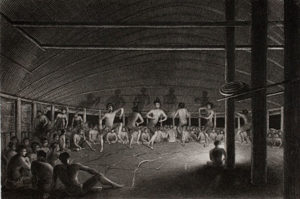

Yet exploration is often a mutual act, as the squadron’s sailors tacitly acknowledged by offering minstrel performances to inquisitive Polynesian onlookers. Charles Erskine, a member of that expedition, wrote in his memoir that while traversing the Pacific Ocean the crew aboard the Peacock “treated the natives to a regular, old-fashioned negro entertainment.” The “natives” were Fijians from the island of Rewa held hostage while awaiting the progress of a manhunt ashore for a key player in the massacre of American sailors some years before. Attempting to entertain their “guests,” the sailors smeared grease on their faces and began to shuffle the decks. Referring to the black dandy “Zip Coon,” a common minstrel character who parodied the “ludicrous airs” exhibited by some northern free blacks, Erskine claimed that “Juba and Zib Coon danced and highly delighted them, [and] the Virginia reel set them wild.” Next, two of the crew tied themselves together, were draped in a blanket, and mimicked the braying of a donkey, while their “comical looking rider, Jim Crow Rice … made his appearance.” Charles Wilkes, expedition commander, thought “the dance of Juba came off well [and] the Jim Crow of Oliver, [the ship’s carpenter,] will long be remembered by their savage as well as civilized spectators.” Indeed, it was the audience, “half civilized, half savage,” which “gave the whole scene a remarkable effect.” The wild popularity of minstrelsy afloat was further hinted at by Wilkes, who claimed that the “theatricals were resorted to” in large part because “the crew of the Peacock were proficients, having been in the habit of amusing themselves in this way.”

It seemed that wherever the fleet moved, the crew insisted on replicating American minstrelsy overseas. In Tahiti, an attempt by officers to stage for the natives a rendition of Friedrich Schiller’s The Robbers fell flat when the “savage” audience began to grumble that there was too much “parau,” or talk. A group of sailors saved the show by smearing their faces and demonstrating “comic songs” popular in America. Wilkes noted in an aside that the Tahitians believed “the rendition of this slow-talking and quick-footed caricature of blacks” was the real thing, “and could not be convinced it was a fictitious character.” Given that much of what could be considered a successful minstrel show within the United States depended upon a knowing interplay between performer and audience, a spectator’s inability or unwillingness to acknowledge the spectacle’s fiction created a radically different dynamic. The failure of native viewers to separate costumed from concrete blackness marks an essential difference between minstrelsy abroad and within the United States, where audiences and performers generally recognized the genre’s conventions and caricatures. When observers were clueless, as at Tahiti, the show’s meaning was up for grabs.

Despite that seeming interpretive instability, however, accounts persisted in emphasizing the positive response of worldwide audiences, as when Francis Hawks noted that minstrel shows “produced a marked effect even on their sedate Japanese listeners, and thus confirmed the universal popularity of ‘the Ethiopians’ by a decided hit in Japan.” Literal diplomatic breakthrough became a function of blackness’ comic skewering overseas. Hawks felt that the two countries became closer to one another in shared mirth over the denigration of African peoples. The chronicler even emphasized that it was at this moment, post-performance, that a Japanese commissioner named Matsusaki chose to embrace Perry, exclaiming “Nippon and America, all the same heart.” It is crucial to emphasize here the “universal popularity” that Hawks, Erskine, and Wilkes alike ascribed to the “Ethiopians,” “Zib Coon,” and “Jim Crow.” American mariners claimed that the sources for mutual understanding—as simple as a collective chuckle—were founded in the ridiculous (mis)representation of black people.

We cannot know how “universal” the delight truly was. More significant is that observers read it as such, citing the goodwill generated by minstrelsy as a potentially unifying force. And U.S. sailors and officers had good reason to laud blackface as a peace maker, for such shows sometimes appeared at moments of imperial crisis within the maritime community. The Perry expedition was in a state of constant tension due to uncertainty over Japanese intentions, while Erskine noted the execution of a blackface show in the midst of a “hostage crisis” at Rewa. Joint laughter at black racial caricatures became an ameliorative tool that allowed peoples at potential odds with one another to temporarily unite in the shared experience of being, in historian David Roediger’s phrase, “Not Black.” Even as sailors disseminated American racial caricatures overseas, they utilized such offensive tropes as the grounds for cooperation with peoples foreign and yet, by right of their ability to find Jim Crow humorous, somehow familiar. Minstrelsy, from the perspective of sailor-performers, at least, became a ritual to construct intercultural solidarities abroad, in the same way some scholars posit that mutual delight among diverse audiences at home produced unity—across lines of ethnicity, religion, and skill—rooted in the “common symbolic language” typifying blackface.

Other observers, meanwhile, commented on the strange effect all of this minstrelsy began to have on peoples overseas. Bayard Taylor, an American traveler who wrote of his globetrotting in 1859, illustrated an interesting scene while in India. Dining with an English gentleman, their meal was interrupted by a Hindu troubadour who began to strum a mandolin for whatever coins the men might spare. But, “to my complete astonishment,” Taylor gasped, the musician “began singing ‘Get out of the way, Ole Dan Tucker!'” Enjoying the Yankee’s surprise, he proceeded to strike up a litany of the era’s most popular minstrel songs, including “‘Oh Susanna!’, ‘Buffalo Gals,’ and other choice Ethiopian melodies, all of which he sang with admirable spirit and correctness.” Further along in his travels, Taylor again spoke of minstrelsy’s global influence: he heard “Spanish boatmen on the isthmus of Panama singing ‘Carry me back to ole Virginny’ and Arab boys in the streets of Alexandria humming ‘Lucy Long.'” And yet, for whatever reason, it was the sound of “the same airs from the lips of a Hindoo” that he had been “hardly prepared” for.

That re-appropriation, however, once again demonstrates the unstable meaning of these minstrel performances: the capacity of audiences abroad to discern what they wished within the show’s song and dance. For even as they blanketed the world, minstrel tunes nominally derisive of nonwhite agency were taken hold of by those very same peoples and repackaged for local use, as worksong, entertainment, or a source of income that preyed on homesick Americans anxious to hear what E.P. Christy saluted as “our native airs.” Clearly, there were peoples around the globe who would dispute the possessive tone of Christy’s comment. Hence the hesitancy with which we must assign any definitive interpretation of minstrelsy’s meaning to overseas audiences. Minstrelsy was immensely complex; contemporary scholars who have examined song lyrics and playbills reveal that it simply cannot be boiled down to the exhibition of exploitative racial imitation. The routines contained many targets and abundant burlesques, all of which changed over time. Not only did the content of blackface performance shift over the course of the antebellum era (with class-based anti-capitalist protest and critiques of elite pretension gradually replaced by more overtly racist representation of black peoples), but so did its aesthetics and target audience.

This in turn begs the question of reception, a notoriously thorny issue even in minstrelsy’s domestic context. What could non-English-speaking observers have gleaned from the shows? Perhaps the Fijians Charles Erskine claimed were “set wild” by Jim Crow saw in the routine nothing more than a variant of the meke dancing indigenous to the islands. Japanese spectators might have projected upon the minstrel performance their own understandings derived from kabuki, given the overlap between theatrical forms that each contained masked actors, slapstick, and song. Due to the scant historical evidence regarding how indigenous viewers perceived sailor minstrels, we may be left with little other than one recent scholar’s scold that to reflexively condemn blackface’s message as racist is to oversimplify. Rather, in explaining the show’s appeal, he urges us not to underestimate the simple “universal human need [for] entertainment” (fig. 6).

It might be most fruitful to consider maritime minstrelsy within a much larger universe of performances exchanged between sailors and other peoples around the world. Often unable to speak one another’s languages, groups thrown into sudden contact relied upon song and dance routines as communicative devices. So it was that the same Fijians for whom Charles Erskine and his shipmates “jumped Jim Crow” in turn treated the sailors to a show. Once the guests were seated by their indigenous hosts, “A big muscular native … commenced beating … on the Fiji drum with a small war club [while an] orchestra consisting of a group of maidens began to play some on two joints of bamboo.” And as this was occurring, multiple men identified as chiefs, with “wreaths of natural flowers and vines twined around their turbans…[and] their faces painted in various styles, some wholly vermillion, some half vermillion the other half black,” began to sway in formation. Erskine found the accompanying music “anything but musical”—it “would fail to be appreciated by a Boston audience” his witticism went—but nevertheless thought the show on the whole enormously entertaining, and so with “a loud clapping of the hands … [thus] ended the matinee.” Sailors may have blackened their faces to “speak” with spectators abroad, but this behavior must be set alongside those same spectators coloring themselves “vermillion” (or any other number of colors) in an effort to reciprocate. No doubt the precise meaning of the Fijian “matinee” remained blunted by Erskine’s cultural tone-deafness. This was no different than the undoubtedly confused responses registered among indigenous onlookers witness to minstrel shows. Yet these mutual misunderstanding produced enough of a visual and aural spectacle to entertain each side of the encounter and thus sustain at least limited dialogue over the course of the ships’ visit.

And if what an audience actually absorbed from said entertainment was ambiguous, the motivations and intended message of mariner performers was no less so. The translated playbill distributed by Matthew Perry among Japanese spectators may have promised “songs and dances of plantation blacks of the South,” but this takes on added meaning when one considers the frequency with which white sailors compared their hard lot afloat to that of the slave’s ashore. Given the minstrel’s characteristic application of dark hues to white skin, it seems a delicious double-entendre that mariner Justin Martin, for example, thought it “might be better to be painted black and sold to a southern planter than be doomed to the forecastle of a whale ship.” Maritime minstrelsy, therefore, may have used slave imagery and melodies as part of a systematic critique of nautical life as “like slavery.” The comic display became a clever means to mask reproaches that officers would otherwise have termed “mutinous.”

The jury may remain out regarding the precise meaning of seafarers’ performative proclivities. But at the very least this was, as Bayard Taylor noted, a process with imperial implication. Remarking on Jim Crow’s growing global presence, the traveler declared that “Ethiopian melodies well deserve to be called, as they are in fact, the national airs of America,” seeing as they “follow the American race in all its emigrations, colonizations, and conquests, as certainly as the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving Day.” Journalist J.K. Kennard likewise remarked that for all the time it took Britain to “encircle the world…’Jim Crow’ has put a girdle round about the earth in forty minutes.” The Boston Post agreed, proclaiming that “the two most popular characters in the world at the present time are Victoria and Jim Crow.” The global significance of an empire-building queen could only be compared to the imaginative empire already erected by American showmen. For while minstrelsy at home was a crucial platform for expansionist rhetoric, the performance of blackface overseas represented also a form of imperialism, a potential colonization of the indigenous mind. It preceded the arrival of significant numbers of African Americans into the wider world, planting the seeds of prejudice in the minds of the show’s curious onlookers, and corrupting the ability of black peoples to control their own global self-presentation. Historian Eric Lott argues that minstrelsy became a field for expropriation, wherein “black people were divested of control over elements of their culture and generally over their own cultural representation.” The same, it seems, was true of their international reputation. Jim Crow would now become a hurdle for African Americans to clear both at home and abroad.

The apparent avidity with which sailors struck up minstrel tunes abroad juxtaposes strangely with then-contemporary political economists celebrating commerce between nations as a cure for all varieties of chauvinism. John Warren’s oration on the subject, for example, lauded “the connections that may be formed by commercial intercourse” as “not only a source of wealth” but also “a reciprocity of kind offices [that] will expand and humanize the heart, soften the spirit of bigotry and superstition, and eradicate those rooted prejudices, that are the jaundice of the mind.” The ameliorative impact of economic interconnection would have been news indeed to white American seamen often engaged with the world on sharply different terms. For all that some people thought commerce a peaceful alternative to empire’s more brutal aspect, as a harbinger of tolerance and connection, it often brought peoples into contact who found such association offensive, and who used the occasion not to preach peace but instruct in intolerance.

Most observers, however, seemed to overlook the means by which minstrelsy made its appearance overseas. Traveling troupes no doubt played their part. But atop the ocean wave stood ready-made minstrel performers prepared to replicate the nation’s most popular form of entertainment for a diverse array of spectators. By blacking up around the globe, young American men brought the baggage of American history to bear upon peoples far removed from the nation’s shores. Minstrel shows were laden with the burden of the country’s past; racism, degradation, misappropriation, all hiding in plain sight between the notes of cheery melodies and plantation “airs.” And so, despite all that would be lost in translation when “Jim Crow” shuffled across the ship’s deck, it seems crucial that American sailors chose to demean black peoples at encounter’s inception, as though that was to be basis enough for future reciprocity. Those appeals, unfortunately, often worked, entangling populations the world over in a racial order Anglo-American in origin but global in implication.

Further Reading

A sampling of the work related to blackface minstrelsy would include William J. Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture (Urbana, Ill., 1999); W.T. Lhamon, Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (Cambridge, Mass., 1998); Dale Cockrell, Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World (Cambridge, 1997); and Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York, 1993).

The most comprehensive account of the Perry expedition, offering both the American and Japanese perspectives, is Peter Booth Wiley, Yankees in the Land of the Gods: Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan (New York, 1990).

There are several good studies of nineteenth-century American maritime history. They include Margaret Creighton, Rites and Passages: The Experience of American Whaling, 1830-1870 (New York, 1995); W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, Mass., 1997); Paul Gilje, Liberty on the Waterfront: American Maritime Culture in the Age of Revolution (Philadelphia, 2004); and Daniel Vickers, Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail (New Haven, Conn., 2005).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.4 (July, 2012).

Brian Rouleau is assistant professor of history at Texas A&M University. He is completing a book on nineteenth-century intercultural encounters between American sailors and peoples overseas.