The sky was blue, the wind was light, and the air was clear on the bright September noon in 1813 when Captain Oliver Perry sailed to victory against the British on Lake Erie. In a hard-fought battle lasting about two and a half hours, the British disabled Perry’s vessel, the Lawrence, and forced him to flee in a rowboat to another ship, the Niagara. Then, from the deck of the Niagara, Perry directed an assault on the British side that culminated in the capture of the entire royal squadron on the lake. Back in Washington, members of the Senate treated the news of this success as a clear indication that the tide of war was turning decisively in favor of the United States. In the midst of the hoopla, at least one prominent Republican went so far as to describe Perry as a dashing lover, who had wooed the Goddess Victory by his gallant courtship. Yet, although most Republicans in Congress hoped to capitalize on the publicity value of Perry’s feat, others were wary of overstating the significance of the battle when so much about the war remained uncertain. News of Perry’s naval maneuvers soon gave rise to a new round of rhetorical skirmishing, one that revealed the role of romantic imagery in patriotic posturing.

The Senate Naval Affairs Committee met to draft a Congressional resolution of thanks to Perry in late December of 1813. The first version of the proposed resolution contained the claim that Perry’s success represented “a victory as decisive and glorious as any ever recorded on the page of history.” But some observers objected that this assertion was more than a bit overblown. Commanding the lake was one thing. Achieving the conquest of Canada, the ultimate goal of the U.S. border action, was quite another.

Senator Eligius Fromentin, then a brand-new legislator from the brand-new state of Louisiana, ventured to remark that, “It is my wish that in our national acts we shall not appear to vapour, or boast our success too highly.” These reservations met swift rejection from his fellow Republican legislators. Senator Charles Tait, of Georgia, a well-known war hawk, countered immediately that he could not accept Fromentin’s criticism. “I, sir,” he exclaimed, “am very far from cherishing a disposition to light up a glare to dazzle the perception of the American people, or the people of any other nation, by a false description of this glorious victory.” No exaggeration was necessary, Tait explained, because “a narration, in the simplest terms, of its true incidents creates admiration and gratitude.”

It may have come as some surprise to Fromentin, therefore, that when Tait proceeded to offer a simple narrative of Perry’s deeds of the day, he cast his naval triumph as a successful romantic romp. Recounting Perry’s move from the Lawrence to the Niagara, Tait gushed, “even after victory had perched on the standard of the enemy, awarding her favor to superior force, Captain Perry, by the gallantry of his continued perseverance, enticed her back into his arms.” Victory, in the form of the winged goddess Nike, had perched for a time on the British flag mast. But the “gallant” Perry had successfully wooed the lovely lady and won “her” feminine favor. Politicians portrayed Perry’s action as the successful suit of a godly lover, one who lured victory away from his rival and into his own embrace.

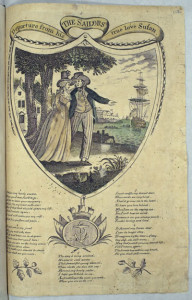

How, and why, did the language of love and romance become the language of war? This evocative language of courtly seduction became key to crystallizing the meaning of Perry’s naval actions because it echoed the themes and concerns that had framed the Republican case for war and that resonated strongly with contemporary popular culture. The image of the sailor as romantic American hero stirred the public imagination on a number of important levels. From the first outbreak of the conflict, American belligerents had insisted that British impressment practices were the provocation that had forced the nation into open confrontation. Portraits of gallant husbands and dedicated fathers severed from their families and compelled to miserable toil in the floating dungeons of an enemy nation proved highly effective in American efforts to dramatize the issue of British impressment.

Polemicists such as Alexander McLeod, a Presbyterian minister and war partisan in New York, insisted that Americans should take seriously the linkages between love, loyalty, and nation. In a sermon that Reverend McLeod called “A Scriptural View of the Character, Causes, and Ends of the Present War,” he promised that “the love of country” would be “revived by this second war of independence.” He declared: “it is not merely for ‘Free trade and sailors’ rights,’ that this contest was intended by the Governor of the world: it was to illustrate … the true nature of allegiance.” According to McLeod, the war was being fought to “maintain the idea that man is as free to choose his residence as his employment, his country as his wife, his ruler as his servant.” Choosing a wife and choosing a country were paired pursuits that together formed the basis of freedom.

Numerous popular poems and songs, published in songster books and broadside posters, used the tale of an impressed sailor torn from his true love to vivify the links between love and liberty. One such tune, narrated in the voice of an impressed man forced to row aboard a British ship, recounted:

I was ta’en [taken] by the foe, ’twas the fiat of fate,

To tare [tear] me from her I adore;

When thought brings to my mind my once happier state,I sigh—I sigh as I tug at the oar.

To heighten the drama, this song presented the sailor not only as a forlorn lover but also as a betrothed man seized and forced into shipboard service on the very morning that should have brought his wedding service. Addressing imaginary lines to “Anna,” his fiancée, he laments:

How fortune deceives! I had pleasure in tow,

The port where she dwelt was in view,

But the wish’d nuptial morn was o’er clouded with woe,

I was hurried, dear Anna, from you.Our shallop was boarded, and I torn away,

To behold that dear ANNA no more.

The song ends, and the sailor finds relief only when he dies of a broken heart. Titled “The Galley Slave,” this song implied that naval impressment was no different than chattel slavery. And the sharpest pain of enslavement came with the loss of love.

Americans and Britons were warring over which nation could lay the greatest claim to loving liberty. Each side sought as its prize the moral right to imperial expansion—Britain in India, the U.S. in North America. Despite the fight for freedom that had once framed the American independence movement, the United States’ continuing and deepening investment in slavery as well as its territorial designs on Native American lands had compromised newer American pronouncements in favor of liberty. When politicians and popular polemicists used the issue of lost love to emphasize the tyrannical side of the British royal navy, they did much to tip the scales of virtue back towards the United States.

These claims framed high politics as well as popular culture. In the opening days of the war, President James Madison’s chargé d’affaires in Britain, Jonathan Russell, claimed that, “in the United States, this practice of impressment was seen as bearing a strong resemblance to the slave trade.” In fact, he went on, compared to enslavement in America, impressment aboard a British ship was actually “aggravated indeed in some of its features.” How could Russell claim that impressing sailors was even worse in some respects than enslaving men, women, and children?

Impressed U.S. sailors suffered more than enslaved Africans did, Russell asserted, because once Africans had been torn from their homeland they had no chance of ever meeting kith or kin again, whereas American sailors forced into British service might very well be put into the position of having to fight against members of their own families. As Russell explained matters, an enslaved African could enjoy “the consciousness that, if he could no longer associate with those who were dear to him, he was not compelled to do them injury.” By contrast, an American tar ran the risk of being “forced, at times, to hazard his life in despoiling or destroying his kindred and countrymen.” The extent of family devastation served as the key index of suffering. Nothing dramatized the threat that Britain posed to the United States like images of American sailors torn from the embrace of their wives and sweethearts.

Sailors pressed into serving the British lost not only their physical freedom but also the right to choose the nation to which they would swear allegiance. In portraying the plight of such involuntary recruits, tableaus of husbands and wives torn apart by British press gangs proved a highly effective way to dramatize the problem. Severing the bonds of love amounted to slashing the basis of liberty. Americans of 1812 equated chosen love with liberty and loyal love with fidelity. Selecting a spouse correlated with the exercise of democratic self-determination, while remaining faithful to the beloved primed people for patriotic allegiance.

American polemicists not only portrayed U.S. sailors as romantic heroes, but they also cast British navy men as rakes and rapists. In reality, a few isolated atrocities werecommitted by servicemen on all sides of the conflict, yet Americans falsely claimed that British Navy made “rape and rapine” systematic policy. So widespread was such anti-British propaganda that when the British attacked Washington, the American physician James Ewell claimed that panicked American gentlemen rode on horseback through the streets of the city crying, “fly, fly: the ruffians are at hand! … for God’s sake send off your wives and daughters, for the ruffians are at hand!” According to Ewell, he received the personal assurance of the admiral of the British fleet, George Cockburn, that American women had nothing to fear. Cockburn supposedly addressed Ewell’s wife directly saying, “Ay madam, I can easily account for your terror. I see, from the files in your house, that you are fond of reading those papers which delight to make devils of us.” As Cockburn rightly observed, newspapers played a key part in popularizing a sexually charged war culture—along with print media of all kinds, from novels and poems to posters and plays.

Cockburn may have diagnosed the problem, but he could not offer any cure. British claims of their own decency held little appeal against white American readers’ delight in tales of British debauchery versus American gallantry. Ultimately, the culture of patriotic ribaldry held sway with the public at large. American men who pictured themselves as the successful suitors and sturdy defenders of the nation’s women felt few qualms about positioning themselves as virile and virtuous proponents of liberty. Concerted complaints about the aberrant sexual behavior of Britain helped inoculate the United States against charges that Americans were the ones engaged in the worst abuses of liberty, from their reliance on slavery to their defiance of Indian territorial rights.

Presenting Perry as a gallant lover who freely won the affections of Victory implied that his triumph was as righteous as it was momentous. The operation on Lake Erie did represent a remarkable win for the usually overmatched forces of the small U.S. navy. Any American naval victory, regardless of its actual strategic impact, gained added significance simply because success against the storied British navy seemed so unlikely. But, more than that, in the mouths of Republicans like Charles Tait, Perry’s conduct proved that America’s fighting men were enflamed by the kind of virtuous love that fed the fires of true liberty.

Unfortunately, by the time the U.S. Senate committee on naval affairs could gather on December 27 to debate the question of whether Perry’s victory had been completely decisive, or simply very glorious, new disastrous events had occurred. Word was then arriving in the capital that the British had seized the American Fort Niagara on December 18, and that combined British and Indian forces were launching attacks across the Niagara Valley. By December 30, the British would burn Buffalo and, in consequence, the U.S. would lose all control of the crucial western frontier between New York and Canada on the east side of Erie. Senator Fromentin raised his objection to the excesses of the Senate celebrations in reference to this reality.

Faced with Fromentin’s inconvenient facts, Tait successfully countered with compelling visions of Perry’s military heroism and romantic powers of seduction. No matter the factual strength of his case, Fromentin gave way before Tait’s superior oratory. Withdrawing his previous critique of the meaning of “decisive,” he conceded, “I am disposed to accept, as more pertinent than my own, the definition which has been offered by the honorable gentlemen from Georgia.” The full resolution citing Perry’s “decisive and glorious” victory passed both houses of Congress unanimously and was approved and signed into law by President James Madison on January 6, 1814.

In strict military and diplomatic terms, the War of 1812 accomplished almost nothing at all. By the war’s end in 1815, after the British had burned Washington, D.C., to the ground and the national debt had nearly tripled, from $45 million to $127 million, all that the United States had managed was to convince the British to return all territorial boundaries and diplomatic disputes to their prewar status. Yet somehow, the population at large regarded the war as a rousing triumph. Madison easily won reelection in November 1812 and his hand-picked successor and former secretary of war, James Monroe, enjoyed landslide success four years later, in 1816. Hundreds of thousands of men cast Democratic-Republican votes in these contests. The war, in other words, proved to be a popular success. Dazzling perceptions were everything.

Further Reading

On the military history of the War of 1812, see Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (Urbana, Ill., 1989). On British-American contests for liberty, see Jon Latimer, 1812: War with America (Cambridge, Mass., 2010) and see Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006). On the political meanings of marriage in the United States, see Nancy F. Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation (Cambridge, Mass., 2000).

For the primary sources quoted here, see: Letter from the Secretary of the Navy, of the Twenty-seventh Instant, to the Chairman of the Naval Committee, together with Sundry Documents (Washington, D.C., 1813); Commodore Perry, or, The Battle of Erie, Containing a Full and Accurate Report of the Proceedings of Congress in Relation to the Gallant Officer and His Signal Victory on Lake Erie (Philadelphia, 1815); Alexander McLeod, A Scriptural View of the Character, Causes, and Ends of the Present War (New York, 1815); “The Orphan Boy; The Galley Slave, and the Sailor’s Return,” American Antiquarian Society, Broadside Ballads from the Collection of Isaiah Thomas, vol. 1 (c. 1812); “Mr. Russell to the Secretary of State, Dated London, Sept. 17, 1812,” in “State Papers Laid before Congress. 12th Congress—2d Session,” T. H. Palmer, ed., The Historical Register of the United States, Part II for 1814, vol. 4 (1816): 1-226; and James Ewell, The Medical Companion … with … a Concise and Impartial History of the Capture of Washington (Philadelphia, 1816).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.4 (July, 2012).