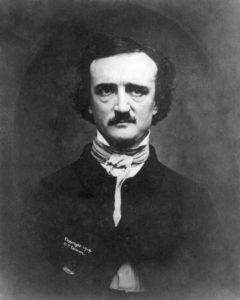

Some doctors who saw Poe professionally denied that he was habituated. Dr. John Carter told a Poe biographer that he “never used opii in any instance that I am aware of, and if it had been an habitual practice,” he and other doctors who knew Poe “would have detected it.” In 1896, Dr. Thomas Dunn English published Reminiscences of Poe, an unflattering portrayal of the late writer. English, however, rejected the notion that Poe was an opium user. “Had Poe the opium habit when I knew him,” he wrote, “I should, both as a physician and a man of observation, have discovered it” during the many occasions when he saw him. He dismissed the allegation as “a baseless slander.” The nature of opium’s effects, however, sometimes made the habit easy to hide.

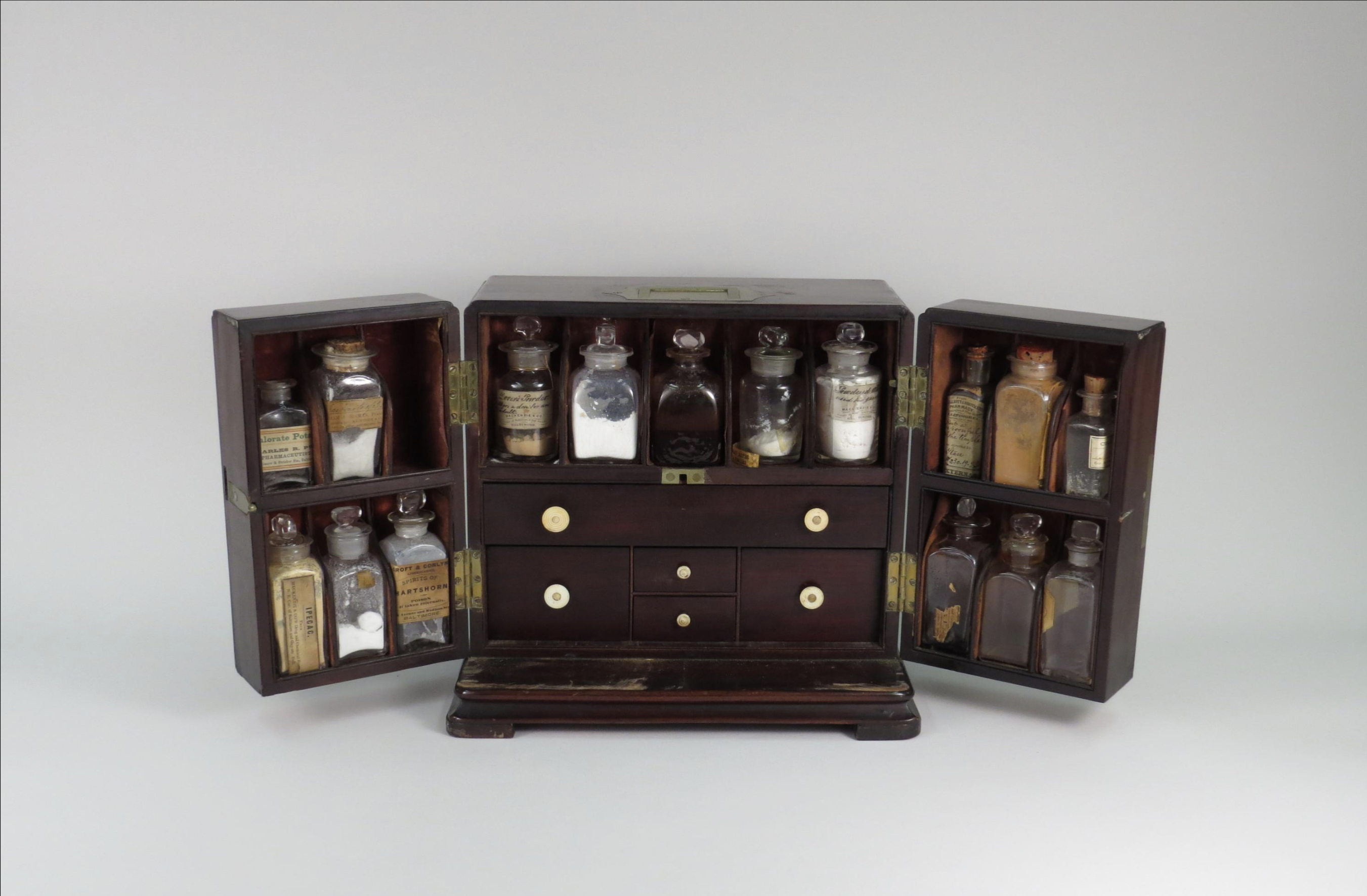

Other evidence is more difficult to dismiss. Helen Whitman was engaged to Poe late in 1848 but ended the relationship due to his drinking. In a letter to her, Poe insisted that he derived “no pleasure in the stimulants in which I sometimes so madly indulge.” “Stimulants” is a peculiarly broad term if he were referring solely to alcohol. (Alcohol and opiates were both characterized as stimulants at the time.) In the summer of 1849, Poe arrived at the home of illustrator John Sartain and begged for his help, as he believed that some men planned to kill him. Poe “piteously begged” him for “some laudanum,” Sartain would recall in 1895. Sartain gave him “a small dose of opium,” to “allay his nervousness.” References to opiates are absent from two other versions of the encounter. It rings true, however, that the agitated poet would have sought out laudanum to calm his nerves.

The strongest evidence of Poe’s opiate usage comes from the research of biographer George Woodberry. As he worked on The Life of Edgar Allan Poe, Woodberry had a helpful research assistant: Amelia Fitzgerald Poe, whose father had been Edgar’s second cousin. In 1884, she visited relatives who remembered Edgar and asked them to share their recollections. She knew that Woodberry’s book could put the author in a bad light, but she rejected the notion that one should not speak ill of the dead. “I fancy that truth is better than fiction,” she explained in a letter to Woodberry, “even though one’s erring relative should be the unfortunate subject.”

Amelia visited Edgar’s cousin Elizabeth Herring, who recalled Edgar’s opium use during the early 1840s. Herring’s recollection is convincing because Poe’s opium use would have been memorable, because she apparently shared her memories unprompted, and because Amelia did not press her on the matter. As Amelia reported to Woodberry:

[Herring] was on a visit to them [Edgar and Virginia] in Philadelphia, where they lived so happily, at the time her cousin Virginia, after singing a great deal one evening, ruptured a blood vessel, from the effects of which she died several years later. [Herring] told me that she had often seen him decline to take even one glass of wine, but says, that for the most part, his periods of excess were occasioned by a free use of opium. I asked if she had any manuscripts or books which she would either lend or sell, but she had nothing.

Woodberry asked Amelia to meet with Herring again, which she did.

In that second session, Amelia asked about Edgar’s opium use. Based on Amelia’s notes, it appears that Herring vividly recalled Edgar’s intemperance. She described not only his opium use but also his friends’ efforts to minimize the damage from his intemperance—likely his use of both opium and alcohol. Amelia wrote:

[Herring] frequently went to see them [Edgar and Virginia] & had the misfortune to see him often in those sad conditions from the use of opium. She says she has seen Mr C or his wife follow him to the gate and take his money & watch away from him when he went out. During these attacks he was kept entirely quiet & they did all possible to conceal his faults & failures. After recovery his penitence was genuine, but he made good resolutions only to be broken.

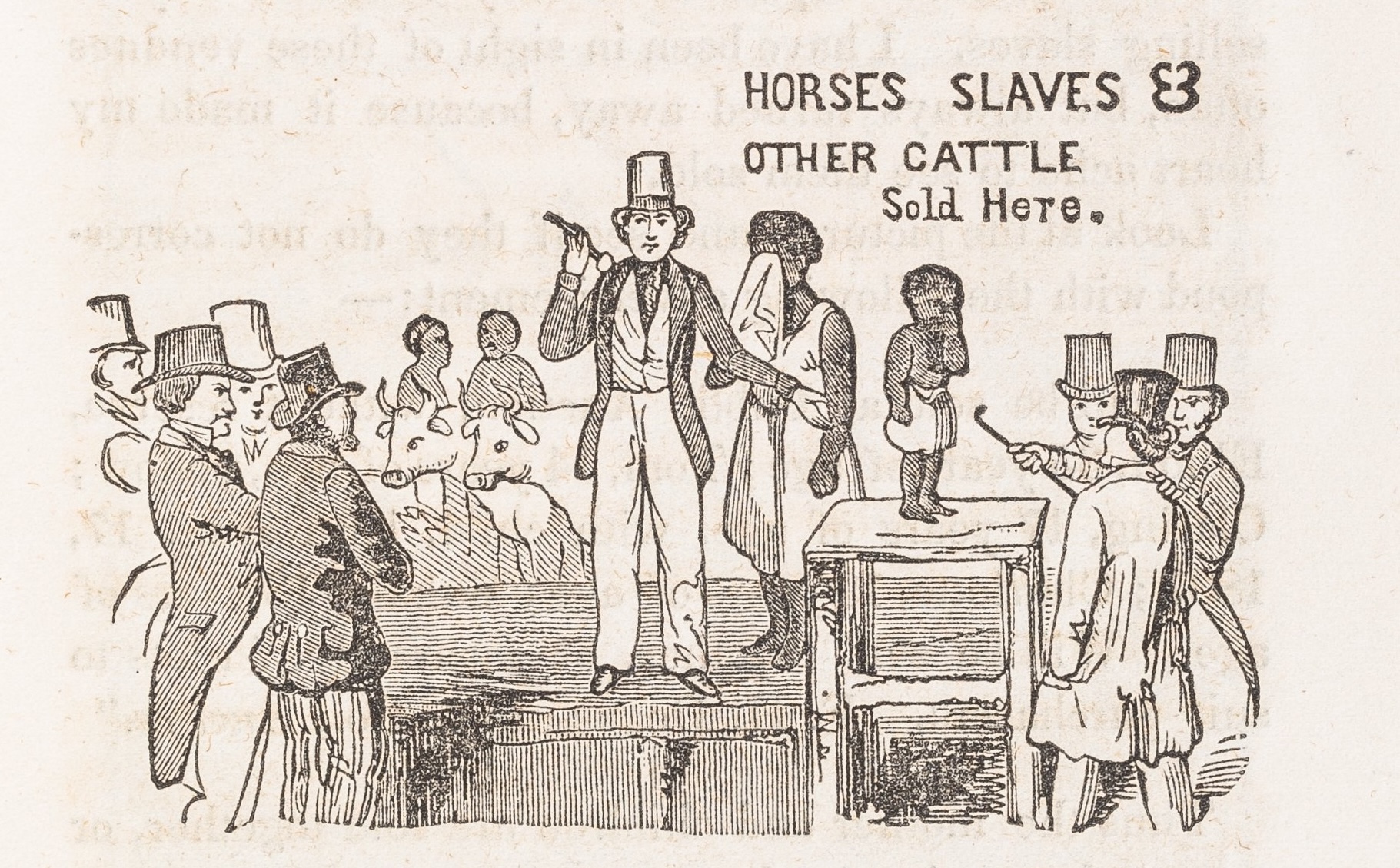

“Mr C” could have been Thomas Clarke, a publisher who worked with Poe in Philadelphia on a new magazine in 1843 but who ended their partnership partly due to Poe’s drinking. (Figure 5)