The belief that Federalists sat grim-faced and hapless as their nimble Jeffersonian opponents developed ways to shape public opinion runs deep in American historical thought. The Federalist press has been portrayed as entirely lacking the agility and ambition of its Republican counterpart; Federalist politicians have been accused of failing to realize they needed to create a network of believers; and the party as a whole often appears in historical accounts as the horseshoe crab of the early republic: a living fossil that played no role in the nation’s ongoing evolution. I’ll leave it to others, including Andrew W. Robertson and Philip Lampi in this very space, to show that Federalists competed electorally — and fiercely — until the War of 1812. What I’d like to discuss is the Federalist press, and I’ll posit something that I hope honors the spirit of this contrarian blog, if not every historical interpretation ever advanced by its management: Federalist literati precociously developed politics as culture, politics as personal expression, politics as a community built through media, and politics as performance. These men and women of letters rejoiced over partisan divisions while other Americans (including more than a few Federalists) still lamented them. And they understood political media to be the art of getting read, discussed, and perhaps even paid, as much as the art of getting things done. Arianna Huffington? Meet Joseph Dennie.

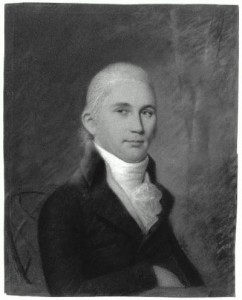

Dennie was a 1790 Harvard graduate who had desultorily set up shop as a lawyer in New Hampshire, all the while trying to establish himself as an essayist and wit, a kind of American Addison. In the mid-1790s, Dennie learned to yoke together the goals and skills of literature and politics, and when he did so, he not only found his voice and livelihood, but also profoundly influenced the Federalist press. Dennie’s two widely read and extracted periodicals were New Hampshire’s Farmer’s Weekly Museum newspaper, which he edited throughout the second half of the 1790s, and Philadelphia’s Port Folio magazine, which he founded and edited from 1801 until his death in 1812.

Politics and Literature: Two Great Enterprises That Went Great Together

Here’s another myth-buster: literature was not a retreat from politics for alienated intellectuals. Literary techniques helped to build the human infrastructure party politics required, and politics offered intellectuals a way to be heard in a country sorely lacking in aristocratic patronage and metropolitan density. Over the course of the eighteenth century, a tradition of witty clubbing — lubricated sometimes by coffee, sometimes by alcohol — had become increasingly entwined with print culture. The educated men and women in England and the colonies who gathered to critique literature, society, and life began to seek publication of their manuscripts in newspapers and magazines. In both their face-to-face gatherings and in print, participants were driven by three desires. They delighted in the sense that their superior judgment and wit differentiated them from the world outside. They wanted to be known to that world outside even as they were convinced of its dull incomprehension. And they wanted to believe that their associations and writings could make that world a better place. These goals — and the tensions between them — readily merged with the intense partisanship of the 1790s. The political parties did indeed have competing understandings of the role of government and competing agendas. But they each also needed to become virtual communities of emotion as well as reason, communities that were simultaneously evangelical and exclusive. Literati, it turns out, were well suited to creating these communities through print. Thomas Jefferson turned to a poet, Philip Freneau, to edit the National Gazette. But it was a Federalist man of letters, Joseph Dennie, who truly excelled.

The literary marketplace in the early Republic had no metropolis, no London to which the aspiring could go and from which power, sales, and influence emerged. In the United States, to convince printers to bring works to press, and to make newspapers achieve anything like a national influence, small but interconnected networks of people worked together to drum up subscriptions. Many of those same people also wished to see their own writing pass through those networks, so they supplied manuscripts to printers and newspapers. Creating a national political party, even a loosely-knit one, required something similar: uniting the work of far-flung networks of amateurs with that of a few professionals, in order to create and circulate ideas and emotions, and to build a community — real as well as imagined — without direct contact.

In both the Farmer’s Weekly Museum and the Port Folio, Dennie larded national and international news with brief, mordant commentary, and he also penned longer essays, such as the “Lay Preacher” series, which combined Benjamin Franklin-style moral pronouncements, acerbic critiques of American politics, and an almost campy display of Dennie’s own melancholic unease. Dennie also printed poems, letters, and essays by readers both famous and obscure, many of whom used metaphors and pursued themes the editor himself had introduced.

Through his astute use of bylines, introductions, and even inside jokes, Dennie made visible the relationships and networks that produced and circulated literary and political content. Both the content and this revealing of the networks were important. The periodicals drew people into a partisan community in which they spread Federalist-inflected anecdotes and rumors, sent in their own political information, and, significantly, learned to see with Federalist eyes and speak in a Federalist tongue. Politicians such as Jeremiah Smith, Lewis Richard Morris, and Robert Goodloe Harper eagerly participated. More generally, Federalist newspapers — like Republican ones — reprinted each other’s work, “linking” to each other in a way that increased awareness of publications and editors and sped circulation of ideas, animosities, and tropes. Successful editors offered their distinctive worldviews and voices, but also offered a forum in which nonprofessionals — in either literature or politics — could find their comments posted, their battles joined, and their turns of phrase admired and emulated.

Federalist Dittoheads

This was participatory print culture, one that openly tried to create an impassioned, hostile interdependence with Republican newspapers, so that passions and readerships might rise. “Since the Editor has been splashed with the mud of Chronicle obloquy,” Dennie wrote gleefully in the midst of one newspaper war, “he has gained upwards of seven hundred subscribers. He therefore requests…the honour and the profit of their future abuse.” Such a print culture is reminiscent not of a hidebound aristocratic past but instead of today’s political/social/cultural websites such as DailyKos and Redstate. Federalists who participated in these newspapers, moreover, realized that jokes, caricatures, and a heightening of the divide between “us and them,” of the sort that flowed naturally from literary club culture, would gain both readers and political adherents. The point was to make participants feel part of an enclave, even as one justified that gated community by insisting one’s goal was to tear down the wall and reform the nation. Thus in Federalist newspapers, broad insults and scabrous doggerel (even John Quincy Adams indulged) drew laughs, while the creation of a private language of allusions, characters, and metaphors gave readers the thrill of being political participants and members, not simply consumers.

A reader of the Museum or the Port Folio brought forward in time would require little explanation of Rush Limbaugh and his 24/7 Club. There was startlingly virulent mockery of political enemies: Thomas Jefferson’s prose, one Port Folio column declared, not surprisingly resembled that of a certain maid named Betty, “for Betty is a long-sided, raw-boned, red-haired slut, and, like Mr. Jefferson, always hankering to have a mob of dirty fellows around her.” There were constant reminders of the difference between Dennie’s faithful readers and the moral and intellectual dullards around them: “When they cast their blinking optics to heaven,” Dennie wrote of the latter in 1805, “[they] can discern nothing there but stones, hard as their callous hearts, cold and heavy, like their calculating heads, and rugged and senseless, like their republican system.” And there were urgent calls to cultural and political arms: “At this moment, my friend,” wrote a 1798 correspondent Dennie identified as “Member of Congress,” “we should have our lamps trimmed and burning, for we know not the day nor the hour, when the Sans Culottes will come upon us.” More likely to keep their inkwells wet than their powder dry, Dennie’s readers nonetheless thrilled to the constant, convivial alarm.

The fact that this Federalist use of the media did not gain the party electoral dominance should not blind us to what it did do. Federalists may have spouted a rhetoric of disdain for the common public — the “swinish multitude” (see how fun that is?) — but Federalist literati wove a net of talkers, writers, readers, and circulators, and strove to shape information, opinion, and allegiance through it. Such sardonic Federalists precociously accepted the fact that democratic politics would never create a univocal public; they embraced partisanship when most Americans still deplored it. They also quickly realized that American political parties needed to create and market identities, not simply agendas.

Responding to the fact that politics is America’s lingua franca, Dennie dressed musings and rants about character, life, and society in partisan garb, and dressed partisan rhetoric in musings and rants about character, life, and society. He offered himself up as analyst, entertainer, and — not least — martyr; seeking a broader audience by selling a feeling of exclusivity, Dennie implicitly told readers that only they could understand him and, therefore, only they could understand what was best for the nation. By such means, this Federalist editor drew readers, contributors, and politicians into a community that foreshadowed the community of listeners, callers, and politicians Rush Limbaugh would build two centuries later. Savvy Federalists saw in Dennie’s periodicals a vehicle that wrapped their proffered bits of information and argument in its air of au courant intimacy, as well as a way to reach a potentially sympathetic and dynamic — but dispersed — audience, an audience who would then pass on the information and the thrill of belonging to others. Dennie’s readers and contributors, in turn, felt included in a highly personal political world. The Constitution made them citizens; Dennie made them members. That their membership in the polity was built on criticism of their countrymen only makes the Port Folio feel more modern. In political communities from DailyKos to Rush 24/7, patriotism burns as an angry love. And so, you heard it here first. Federalists? They were ahead of their time.

FURTHER READING

For other scholarly accounts of Federalist literary journalism, see Lawrence Buell, New England Literary Culture: From Revolution through Renaissance (Cambridge University Press, 1989); Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility: Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy (Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2008); William C. Dowling, Literary Federalism in the Age of Jefferson: Joseph Dennie and the Port Folio, 1801-1812 (University of South Carolina Press, 1999); Linda K. Kerber, Federalists in Dissent: Imagery and Ideology in Jeffersonian America (Cornell University Press, 1970); and David S. Shields, Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America (University of North Carolina Press, 1997). Google Books has much Dennie-ana available for full-text download, including an 1817 collection of the Lay Preacher essays, 26 issues of the Port Folio‘s “new series” from 1806, and a 19th-century biography that reprints a number of Dennie’s letters.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).