A boy was born in Amabou, Ghana, in 1750. His father was a hereditary leader of his place, but whether we call him a king, a lord, a chief, or a headman, is a matter of custom and cultural perspective. Let’s call him a king after the English fashion. This ruler, seeing the obvious power and influence of the English seafarers, traders, and missionaries who crowded the coast in increasing numbers, decided it was wise for his son to study their ways and arranged with a ship captain to take him to America to get an education. An older relative had previously made this journey and returned with a Christian education. It is not known where he thought to send them, though there were renowned missionary “negro schools” in New York and Philadelphia and academies in New England who would accept Native Americans and other pupils of color.

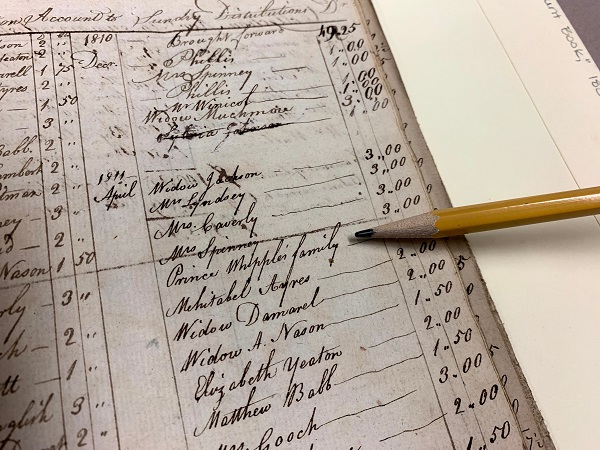

After some sort of deal was struck with an English or American captain to take the now ten-year-old boy and his younger brother and conduct them to the school, either the captain changed his mind en route and simply the kept the boys as his own slaves, or the ship was seized by pirates and the boys sold off with the other prizes, or the captain sold them himself once he arrived in an American port. What is known for sure is that the African boys were claimed by a former slave ship captain who lived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1765.

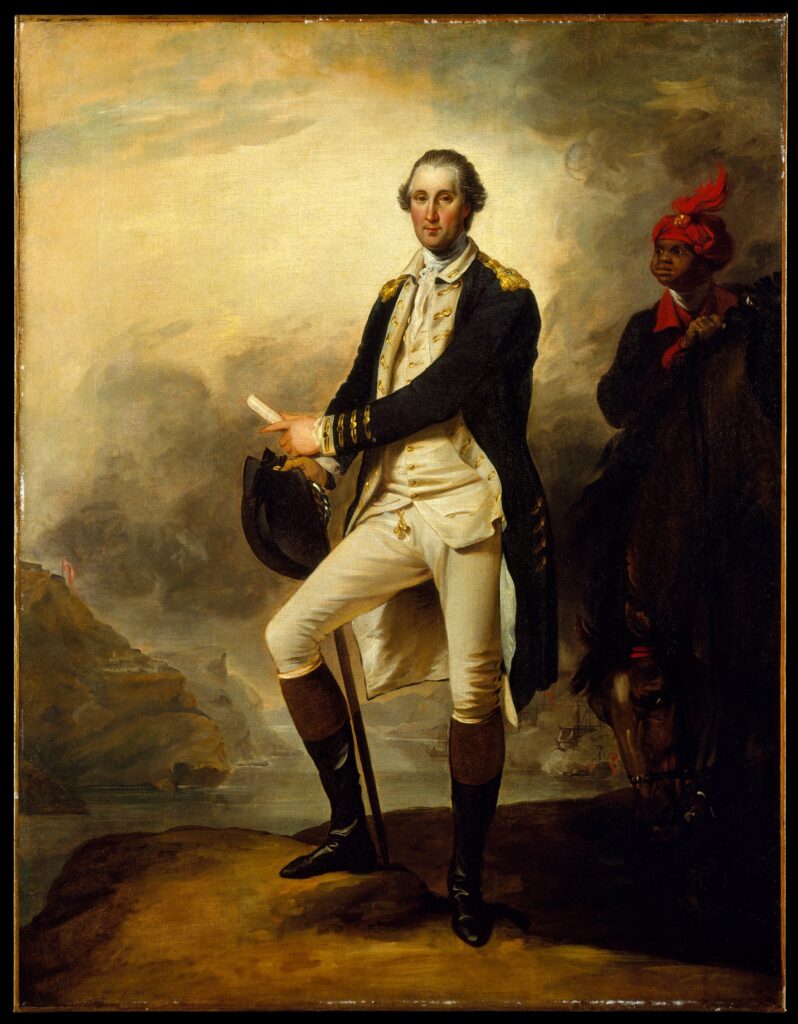

That ship captain, named William Whipple, was born in Maine in 1730 and like many boys who grew up along the great harbors and inlets along the Piscataqua River that divided the state from New Hampshire, Whipple went to sea at a young age. He proved himself a skilled mariner and by the time he had reached his twenties he captained his own ship. Like much of the rest of the American fleet, Whipple plied the Africa trade, carrying rum eastward and human beings west. Such trade was so handsomely profitable that Whipple could afford to marry his cousin and retire to the relatively quiet life of a town merchant before he reached the age of thirty.