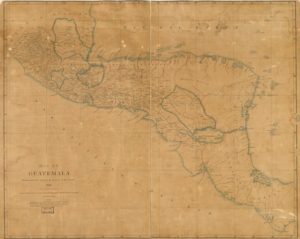

And as the imprecision of the country’s name at its moment of U.S. recognition suggests, the politics of Central America were unstable in the mid-1820s. Later in the decade and into the 1830s, as civil war destroyed the Central American union, foreigners mined the colonial archives and traveled the countryside producing and circulating scientific data that conformed to European conventions and would be more useful to foreign capitalists than local farmers. Science in Central America became less provincial just as the provinces became their own nations with the familiar names we know today.

Foreign canal dreamers from the U.S., Netherlands, France, and Britain would employ this scientific knowledge to promote interoceanic waterway projects in the Republic of Nicaragua throughout the nineteenth century. In the early twenty-first century, more than a hundred years after the opening of the Panama Canal, interest in constructing a waterway through Nicaragua persisted. Reversing the direction but not the dream, the most recent canal contractor sought a waterway to link his nation, China, with its Atlantic trade partners.

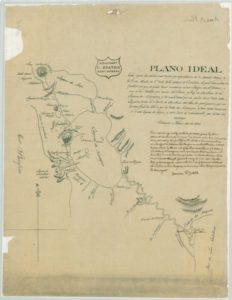

Plans for a Nicaraguan waterway have a long history, but there’s something special about the 1820s quest for a Central American canal. Without access to the types of scientific data that informed later proposals, the would-be canal constructors of this era blindly and optimistically envisioned the creation of a world-changing waterway. They proceeded despite their ignorance. In place of information, they relied on their imaginations. Dreams substituted for data. Ultimately, their canal dreams proved impractical, but quite influential. The idea that an interoceanic waterway could and should be constructed shaped international diplomacy, launched scientific investigations, and contributed to speculative enterprises on both sides of the Atlantic.

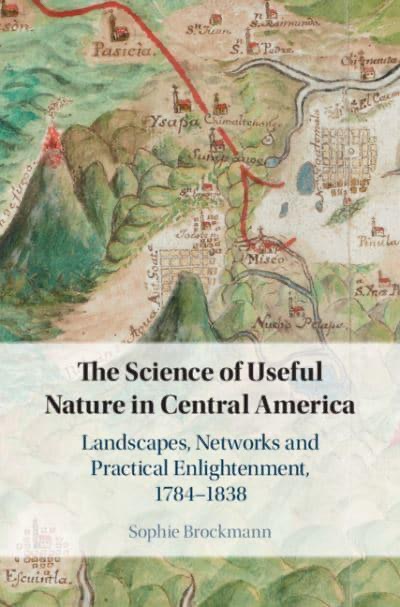

Unknown to them, the region was not quite as mysterious to everyone. Before I read Brockmann’s book, I was inclined to agree with Adams and the authors of my other primary sources who argued that the isthmus was an obscure place that was scientifically unexplored. Brockmann’s research and her insightful arguments taught me not only that plenty of knowledge production occurred in Central America before the 1820s but also that this “practical” information was designed to serve locals rather than foreigners. Applying these conclusions to my own research, I realized that the people who best knew the isthmian land most valued by the rest of the world likely protected their knowledge. The inhabitants of Central America’s aqueous treasure might want to keep their lands a mystery to keep their lands.

The early nineteenth-century systems of knowledge creation and dissemination that served Central American locals rather than foreigners provides an answer to the question of why an intriguing place central to the Americas and a thousand miles closer to Washington, D.C. than San Francisco was so unknown in the early U.S. republic. Moreover, because this terra was intentionally incognita, its significance to U.S. history has also been obfuscated. The primary sources claimed ignorance, and the secondary sources generally looked no further.

But what can we know from what early Americans didn’t know? It is hard for historians to see the significance of something unknown and unbuilt. We tend to truck less in undoable dreams and more in the definitively done. The Panama Canal incontestably made history, but could history also be made of imagined waterways? I think so. If we squint, we can see treasure hidden in the absence of firm historical ground.

Further Reading

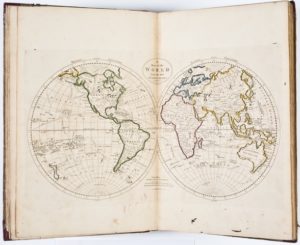

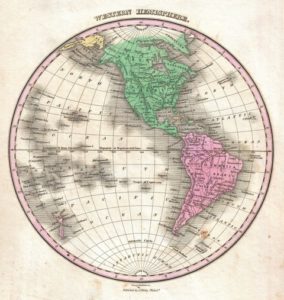

Sophie Brockmann’s The Science of Useful Nature in Central America: Landscapes, Networks and Practical Enlightenment, 1784-1838 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020) is a thorough investigation of early Central American science. For Central American political history in the era of independence, see Jordanna Dym’s From Sovereign Villages to National States: City, State, and Federation in Central America, 1759-1839 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006). For the collapse of the Central American republic, see Thomas L. Karnes, The Failure of Union: Central America, 1824-1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961). The older historical literature on the Indigenous nations of Eastern Nicaragua often focuses on British influence in the region. For example, see Craig L. Dozier, Nicaragua’s Mosquito Shore: The Years of British and American Presence (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985). Recent journal articles by Damian Clavel, Matthew P. Dziennik, and Caroline A. Williams center the Miskitú in the region’s history. For a current map of the homelands of Miskitú, Rama, Mayangna, and other Indigenous communities, see https://native-land.ca/. My thinking on the cartography of Central America owes debts to many of the essays in Jordana Dym and Karl Offen, eds., Mapping Latin America: A Cartographic Reader (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); I am especially drawing on essays by Dym, Offen, Matthew Restall, W. George Lovell, and Christopher H. Lutz. For U.S. hemispheric diplomacy and popular perceptions of the new Spanish American nations, see James E. Lewis, Jr., The American Union and the Problem of Neighborhood: The United States and the Collapse of the Spanish Empire, 1783-1829 (University of North Carolina Press, 1998); and Caitlin Fitz, Our Sister Republics: The United States in an Age of American Revolutions (New York: Liveright, 2016).

The quotations from State Department documents can be found in various microfilms at the National Archive at College Park, Maryland. John Quincy Adams’s narrative account of Central American Recognition can be found in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s John Quincy Adams Digital Diary for August 4, 1824. The Central American legislator who argued for canal data was later the president of the post-independence Economic Society; his speech can be found in José del Valle and Jorge del Valle Matheu, eds., Obras de José Cecilio del Valle (Guatemala, 1929). I am grateful to James Irving for his eloquent Spanish to English translations and to Michael Dube, Julia Rodriguez, Joshua Greenberg, Jordan Taylor, and an anonymous Commonplace editorial board member for their insightful suggestions.

This article originally appeared in April 2022.

Jessica Lepler is associate professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. Her first book, The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis (Cambridge University Press, 2013), won the James H. Broussard Best First Book Prize from the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic. She is currently writing a book on the 1820s quest for a Nicaraguan interoceanic canal.