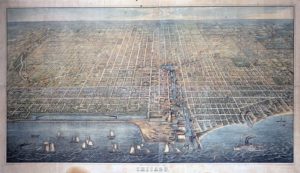

William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West is a Big Book. Hefting it onto my lap for another read put me in mind of similar attempts to hold Eric Foner’s Reconstruction in just one hand. But like Reconstruction, Nature’s Metropolis is a Big Book because thirty years ago, it advanced a landmark argument that no subsequent scholar of its subject can well ignore. William Cronon presents in Nature’s Metropolis an assertion of the fundamental interconnectedness of the city and the countryside. This is figured in the history of Chicago, primarily in the nineteenth century, as the city grew from the commodification of the produce of its rural environs. Rather than depicting a one-way transaction in which the city grew at the expense of its rural neighbors, Cronon argues a “twin birth of city and hinterland. Neither was possible without the other” (264).

Nature’s Metropolis at 30

William Cronon presents in Nature’s Metropolis an assertion of the fundamental interconnectedness of the city and the countryside. This is figured in the history of Chicago, primarily in the nineteenth century, as the city grew from the commodification of the produce of its rural environs.

As Thomas Andrews observes in his contribution to this retrospective, Cronon’s gift for clarity as a writer leads him to declare in his preface what Nature’s Metropolis will do, and what it will not do. “I have little to say,” he cautions, “about most of the classic topics of urban history . . . Readers turning to this book for an account of Chicago’s architecture, its labor struggles, its political machines, its social reformers, its cultural institutions, and many other topics are likely to turn away disappointed” (xvii). Nature’s Metropolis is known to many historians as a classic of environmental history and, as Cameron Blevins will point out here, spatial history. But for those of us who specialize in African American history, this, too, at first seems to be another one of those topics on which Cronon will have “little to say.” African Americans are absent from the book’s index. A rare mention appears in Cronon’s third chapter, on grain, from Chicago boosters crowing about the efficiency of their city’s grain elevators; by comparison, they ridiculed the continued reliance in St. Louis on moving sack loads of grain from ships to warehouses through “the labor of probably two or three hundred Irishmen, negroes and mules” (112). And Cronon’s exclusion of African Americans from his later chapter examining motivations for rural residents to migrate to the city is curious indeed.

But Nature’s Metropolis offers a great deal to students of African American history. Much has already been written about black life in Chicago, particularly during the First and Second Great Migrations. The title of Cronon’s work calls forth that of St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton’s sociological study of black Chicago, Black Metropolis. Cronon’s emphasis on the inseparability of city and country can be fertile ground for African American historians. Post-emancipation African American history is closely tied to urban history, for good reason as thousands of former slaves and their descendants left the Jim Crow rural South for opportunity in places like Atlanta, Detroit, and Chicago. But how might we reorient our perception of that history if we understand cities not as isolated sites of relative opportunity for African Americans, but as tied to their hinterlands? Tied not just in terms of the exchange of money for grain or lumber, as Cronon describes, but also in terms of family and kinship, with consequences both empowering and devastating? Recall, as just one poignant example, that the young black Chicagoan Emmett Till was in Mississippi to visit an uncle when he was lynched in 1955. I am reminded of the twenty black ministers who met with William Tecumseh Sherman in January 1865, with the end of the war and abolition looming, to inform him, “We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.” Even before this, generations of black pioneers in the Old Northwest built farmsteads of their own, as chronicled in Anna-Lisa Cox’s The Bone and Sinew of the Land. African American urban migrants remained parts of extended families whose own networks stretched from country to city, from slavery to freedom. If, as Cronon shows in his work, capital moved back and forth between city and country, in African American history, we may well trace a similar exchange of things perhaps less tangible but no less central to the American story: family, striving, and love.

Francesca Gamber

Bill Cronon and the Art of Historical Storytelling

I have just set down Nature’s Metropolis after my umpteenth reading. Each time since I first cracked its cover back in 1993, this landmark book has left me with something new. This go-round, one word cuts right to the heart of what I most admire about Bill Cronon’s magnum opus: clarity.

Nature’s Metropolis makes for beautiful reading because of the laser-focused acuity that Bill lavished on every sentence, paragraph, section, and chapter (not to mention each endnote, data routine, and mortgage map). The book is clear because Bill knew what he wanted to say, he cared about communicating his insights to audiences well beyond academe, and—moving from intention to execution—he understood the alchemical processes whereby crisp, purposeful prose and flawlessly constructed arguments can catalyze pure gold. Thirty years after its publication, Nature’s Metropolis remains a must-read for any serious student of U.S. history because Bill possessed the conviction and skill needed to make big, important ideas accessible. Throughout the book, he takes his readers by the hand and tells them stories that reveal the marvels of such seemingly banal topics as railroad rate-setting, commodities markets, and capital flows. Paradoxically enough, the clarity that strikes me as the book’s defining triumph accentuates these subjects’ complexities instead of flattening them. Writing around the height of the “literary” or “cultural” turn in historical studies—a time when many historians were aping the prolix, jargon-ridden mannerisms of postmodern and post-structuralist theorists—Bill self-consciously chose to advance a more inclusive historical vision.

A book of such richness and quality prompts any number of reactions, but I am hardly the only reader enticed by the lucidity of Nature’s Metropolis. Bill Cronon’s masterful study continues to inspire undergraduates and graduate students, environmentalists and commodities traders, academic historians and regular folks to see something of themselves in the first-person narrative with which Bill famously starts and ends his story—and, more important, to see their own world afresh through the lens of Chicago and the Great West. Many years after my initial foray into this justly treasured book, its crystalline quality continues to impress me as the wellspring of its many wonders.

Thomas Andrews

The Spatial Framework of Nature’s Metropolis

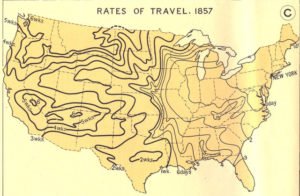

Nature’s Metropolis is a book about spatial flows; think of hogs transported from Iowa feedlots to Chicago stockyards to New York dinner tables, or mail-order goods and lines of credit moving in the opposite direction. It is a history of how the movement of commodities and capital remade the geography of Chicago, its hinterland, and the larger United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. It is, in short, a work of spatial history. Spatial history is, broadly speaking, the study of how spatial relations and geographical patterns shape historical processes. Emerging from the theory-driven “spatial turn” in the humanities and social sciences in the late twentieth century, spatial history now encompasses digital methods such as Geographical Information Systems (GIS) software and data visualization. Nature’s Metropolis was an early landmark in this field.

William Cronon weaves a series of spatial concepts throughout Nature’s Metropolis, including central place theory, “first” and “second” nature, and the geography of capital. What sets him apart, however, is the way he historicizes these otherwise abstract geographical models, grounding them in contingency, context, and change over time. For instance, central place theory—the idea of concentric rings of economic activity radiating out from a city—helps explain Chicago’s relationship to its hinterland. But Cronon also highlights how these relationships were dynamic and ever-changing and how Chicago’s rise as a gateway city for national and European markets muddles the city’s status as a central place.

Cronon’s work as a spatial historian culminates in chapter six, “Gateway City.” Here, he goes beyond abstract spatial concepts. Using the statistical software SAS and SASGRAPH, Cronon collected quantitative data on creditors and debtors during the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath and then analyzed regional bankruptcy patterns through a series of twelve choropleth maps. Unlike the typical maps that appear in historical monographs, these maps don’t just show geographical context; they explicitly advance Cronon’s larger argument about the flows of capital that knit the region together.

From Cronon’s use of spatial theory to the book’s more than two dozen maps and charts, Nature’s Metropolis foreshadowed the rise of spatial history in the decades to come. By the early 2000s, groups of social scientists and historians using mapping software had coalesced under the banner of Historical Geographical Information Systems (HGIS). This development went hand-in-hand with the concurrent rise of digital history, a methodological embrace of computers to analyze and communicate history. In the book’s appendix, Cronon spends several pages detailing the technical aspects of how he collected and mapped the data—an explicit emphasis on methodology that would define many future spatial (and digital) history projects. The technology has changed dramatically in the intervening decades, with mainframe computer terminals and SAS software giving way to ArcGIS, interactive web mapping, and mobile interfaces. But Cronon’s melding of geographical and historical analysis to illuminate the environmental, urban, and economic history of the United States has ensured that, thirty years later, Nature’s Metropolis remains an enduring model for spatial historians following in his path.

Cameron Blevins

First Nature’s Sex: Nature’s Metropolis and the History of American Sexuality

The history of environment and the history of sexuality are subfields of American history that arguably share less conversation than any two other subfields I can name. Among environmental historians, Nature’s Metropolis is regarded as a towering and field-defining work. Yet historians of American sexuality seldom write much about it. Yes, they know of Nature’s Metropolis and may have read it in a graduate methods class or perhaps in relation to urban historiography. But the major concerns of Nature’s Metropolis are sometimes assumed to be remote to those that concern historians of sexuality. This is an odd assumption, I would contend, because both the book and historians of sexuality are preoccupied with how capitalist modernity has formed American cityscapes.

Nature’s Metropolis argued that the capitalist transformation of the American West proceeded through the commodification of the nonhuman world with, at each stage, the nonhuman world becoming more estranged from the particularity of its emergence and living variation, its “first nature.” Heterogeneous nature was reified as exchangeable, abstracted objects, and once so commodified they became the substance of capital, finance, debt, loans, and futures contracts. The physical worlds emerging from this assemblage—Chicago, most notably—were no less “nature,” but they were nevertheless a “second nature,” a human redirection, if not mastery of “first nature” (xix).

Nature’s Metropolis describes these processes as distributed and diffuse. Technologies of abstraction and production were not located exclusively in the metropolis but also in peripheral landscapes popularly characterized as “closer” to nature. Similarly, these processes operated through individual bodies sorting individual kernels of corn, but it was also composed of commodity flows where markets traded on the futures of those aggregated commodities. The capitalism described in Nature’s Metropolis is, like the repressive hypothesis, laid across the entirety of the social body and it bridles the multiplying nonhuman energies within that body: corn, meat, trees—things that grew, multiplied, and varied through the uncanny immanence we call life.

This point is central to how the book describes the moralized meanings ascribed to the nature/culture boundary. “The boundary between natural and unnatural,” Cronon writes, “shades almost imperceptibly into the boundary between nonhuman and human, with wilderness and the city seeming to lie at opposite poles—the one pristine and unfallen, the other corrupt and unredeemed” (8). Later he described the ambivalence nineteenth-century Chicagoans attached to that moral geography:

If the city was unfamiliar, immoral, and terrifying, it was also a new life challenging its residents with worldly success, a landscape in which the human triumph over nature had declared anything to be possible. By crossing the boundary from country to city, one could escape the constraints of family and rural life to discover one’s chosen adulthood for oneself. Young people and others came to it from farms and country towns for hundreds of miles around, all search for the fortune they believed they would never find at home. In the words of novelist Theodore Dreiser, they were ‘life-hungry’ for the vast energy Chicago could offer to their appetites (13).

This is the same history of sexuality John D’Emilio provided in “Capitalism and Gay Identity” and that George Chauncey offers in Gay New York, although one in which sexuality is hustled in through euphemism. Nineteenth-century Americans, of course, understood precisely this “triumph” over “nature” and “the constraints of family” in explicitly sexual terms, with the race, gender, and class-mixed spaces of urban America, and Chicago in particular, a major source of sexual anxiety and “appetite.” The empirical fact of America’s emergent urban sexual subcultures in the period is beyond dispute, even if this framing relegates them to the “second nature” of social forms freed from a static and ahistorical “familial constraint.” But what sex is then “first nature” in Nature’s Metropolis?

In the late nineteenth century, the physical transformation of the bodies of livestock through improved breeding led to dramatic productivity gains in American agriculture. In fact, by 1900, livestock were the second largest asset class in the United States, after land, and were worth more than the entire capitalized value of the railroads. The logistical improvements described as “the annihilation of space” were coextensive and interwoven with these bodily transformations. For example, aggressive and rangy “long-horned” cattle did well on cattle drives, but they were disasters in confined railcars. Similarly, the growth of corn feeding and finishing as a value-adding process depended on the in-breeding of European shorthorns that added weight from grain-feeding efficiently.

Much of this is euphemistically described as the transition from “extensive” to “intensive” livestock breeding. The sanitized syntax of “intensivity” conceals the technologies, not to mention visceral interspecies interactions, necessary for all this mating to be made. The bodies of breeding animals were the focus of capillary biopolitical governance invested in selectively reproducing livestock life. This governance encompassed a wide array of objects and actors, much of it underwritten by the late-nineteenth-century American state: institutions like breeding associations that guaranteed robust national and global markets for breeding stock; reliable adoption of pedigrees and access to breed herd books to track lineage; improved technical understandings of mechanisms of inheritance and the biology of animal reproduction; record keeping practices to assess and evaluate traits; movements to eradicate scrub animals and limit their influence on bloodlines. Beyond bodily improvement, still other developments reshaped the reproductive behavior of livestock in light of the temporal demands of markets. These included, first and foremost, the more systematic monitoring and regulation of fertility, which could only be accomplished through the increasing spatial organization of animal breeding and the systematic segregation of breeding from feeding stock. This trend reached its apotheosis in the “breeding crate,” a box that physically confined swine during sex, supported the weight of large boars, and prevented small sows from fleeing them. Meanwhile, breeders devised and publicized elaborate feeding and exercise routines, as well as aphrodisiacs, to synchronize animal desire with the calendar demands of the market.

In short, the redaction of animal reproduction in Nature’s Metropolis—its organization and regimentation—is the process by which animal sex is re-natured and narratively ascribed to a self-sufficient heterosexual nature. Farmers need only skim the fat from an innate animal heterosexuality, and the material and ideological organization of that process falls from the purview of historical analysis. The capitalist transformation of the American West described in Nature’s Metropolis was propelled by an intensive deployment of these technologies to produce and multiply new forms of life at ever greater rates, and we must see this relationship between capital and non-human reproduction as key to the functioning of industrial capitalism in the period. Such an approach would be indebted to Nature’s Metropolis, but it would also seek to write a history Cronon that did not, a history as profound for our knowledge of sexuality as for our knowledge of the environment: that is, a queer environmental history.

Gabriel N. Rosenberg

What’s not in Nature’s Metropolis also makes it great

When I think about Nature’s Metropolis I think about movement. Cronon draws readers’ attention to distance, time, and the increased pace of movement of everything as America industrialized. To Cronon, things change just as much when they move across space as they do when they move through time. Admittedly Nature’s Metropolis influenced countless historians, including myself, to use the word hinterland more than we should, and it probably convinced the same amount to make forays into geography.

The force facilitating the increased pace of movement was abstraction, a concept not unique to this book but one which Cronon illustrates so well that the term gains new implications. In Nature’s Metropolis, abstraction is, in short, when the material becomes intangible, fluid, and most importantly, more manipulatable by people. Cronon shows what happens when configurations of atoms—a bushel of wheat, a pork belly, or a log—become a numerical value. This focus on commodities, distance, time, speed, and abstraction means that people are the least memorable part of the book. When I first read the book while training in labor history in graduate school, this lacuna was off-putting, as my margin notes express. It was also inspirational.

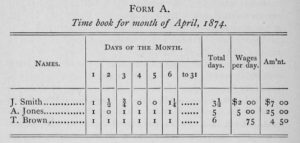

After reading, rereading, and assigning Nature’s Metropolis in my classes, I became convinced that what happened to commodities also happened to labor as America industrialized. Clocks, double-entry bookkeeping, punch cards, all the parts of the modern wage system made labor-time into abstractions which, like Cronon’s commodities, became intangible, fluid, and manipulatable. When labor-time becomes a number—the product of time worked and wage rate, for example—it could then be moved over great distances at rapid speeds. Trains, telegraphs, and telephones allowed payment to be transferred to a logger in the woods of Wisconsin from a bank in Chicago, once proof of work was sent to the bank. Making labor into abstractions opened new avenues of labor exploitation compared to times and places when labor-time was represented as a product sold locally by its producer. We can’t credit Cronon with conceiving of the idea of abstraction, but he can be credited with focusing attention on the mediums of abstraction and movement.

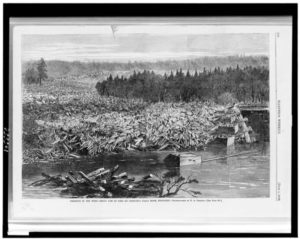

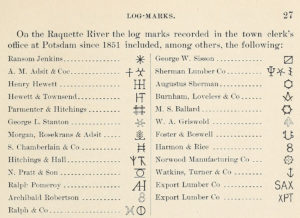

Directly inspired by Nature’s Metropolis’s focus on mediums, I began to research a unique medium of abstraction and movement, the “driving” of free-floating individual logs on American rivers. While log driving might seem pre-modern or antiquated, once this process was systematized around the 1860s, it greatly increased the speed and efficiency of the movement of forest products and labor. When individual logs were marked or branded for driving, this mark came to represent not just the value of the tree but also the value of the labor that went into producing the log. While the log itself was valuable, the value was connected only to the mark. The actual owners of logs could no longer claim those logs if they were erroneously left unmarked, if they were nefariously re-marked, or if they lost their marks on the drive. The medium of abstraction created the conditions for the increased manipulation and exploitation of abstracted labor-time.

Once someone reads Nature’s Metropolis they can’t help but see the world in terms of abstractions in motion. Moving into the information age, labor-time has become more easily and more commonly abstracted, sometimes with troubling results. According to the study referenced below, time clock algorithms are abstracting labor at an astounding rate and volume. The authors estimate that some $15 billion have been stolen from workers through keystrokes and computer errors. Labor is treated so callously because modern economic relations demand that abstractions move nearly instantaneously.

Nature’s Metropolis reveals present problems with media of abstraction and provides foresight into future problems. The idea of “income share agreements” for college students, originally proposed by Milton Friedman in 1955, has gained popularity in the last five years. Under this proposed system, students could avoid college debt by engaging in agreements with investors who would fund their education in exchange for a share of future income. Given the level of student debt in the U.S. this is not on its face reprehensible. The reader of Nature’s Metropolis, however, would be quick to wonder what might happen when student-investments are transformed from curious undergraduates into abstractions that can be traded on four-year future markets, or even bundled into investment vehicles. It is no exaggeration to say that Nature’s Metropolis changed the way that I comprehend the world, revealing the layers of fictions that sit on top of, and shape, labor, nature, and economic relationships in the past, in the present, and in possible futures.

Jason L. Newton

Further Reading

Anna-Lisa Cox, The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality (New York: PublicAffairs, 2018).

St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1945).

Jo Guldi, “What Is the Spatial Turn?,” Spatial Humanities, Scholar’s Lab, University of Virginia, 2011, http://spatial.scholarslab.org/spatial-turn/.

Newspaper Account of a Meeting between Black Religious Leaders and Union Military Authorities, in New-York Daily Tribune, February 13, 1865, Freedmen and Southern Society Project, http://www.freedmen.umd.edu/savmtg.htm.

Alan Olmstead and Paul Rhode, Creating Abundance Biological Innovation and American Agricultural Development (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (New York: Broadway Books, 2016).

Gabriel N. Rosenberg, “No Scrubs: Livestock Breeding, Eugenics, and State Power in the United States, 1919- 1933,” Journal of American History 107, no. 2 (September 2020): 362-87.

Gabriel N. Rosenberg, “A Race Suicide Among the Hogs: The Biopolitics of Pork in the United States, 1865-1930,” American Quarterly 68, no. 1 (March 2016): 49-73.

Joshua Specht, Red Meat Republic: A Hoof-To-Table History of How Beef Changed America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

Elizabeth Tippett, Charlotte S. Alexander, and Zev J. Eigen. “When Timekeeping Software Undermines Compliance,” Yale J.L. & Tech 19, issue 1 (2018).

Richard White, “What Is Spatial History?,” The Spatial History Project, 2010, http://www.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/pub.php?id=29.

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010).

Rebecca Woods, The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800–1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

This article originally appeared in December 2021.

Contributors:

Francesca Gamber is a member of the editorial board of Commonplace. She is the Principal and Faculty in History at Bard High School Early College Baltimore.

Thomas Andrews studied with Bill Cronon at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He teaches and writes about the social and environmental history of the U.S. West at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Cameron Blevins is Associate Professor, Clinical Teaching Track at the University of Colorado Denver. A leader in the field of digital history, he is the author of Paper Trails: The US Post and the Making of the American West (2021).

Gabriel N. Rosenberg is Associate Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies and History at Duke University. He is currently writing a history of livestock breeding and its relationship to human race science, tentatively titled, Purebred: Making Meat and Eugenics in the Modern United States.

Jason L. Newton (https://capitalismstudies.charlotte.edu/postdoctoral-fellow) is the post-doctoral fellow in the history of capitalism and environmental sustainability at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. He tweets @Jason_L_Newton and his work can be found here.